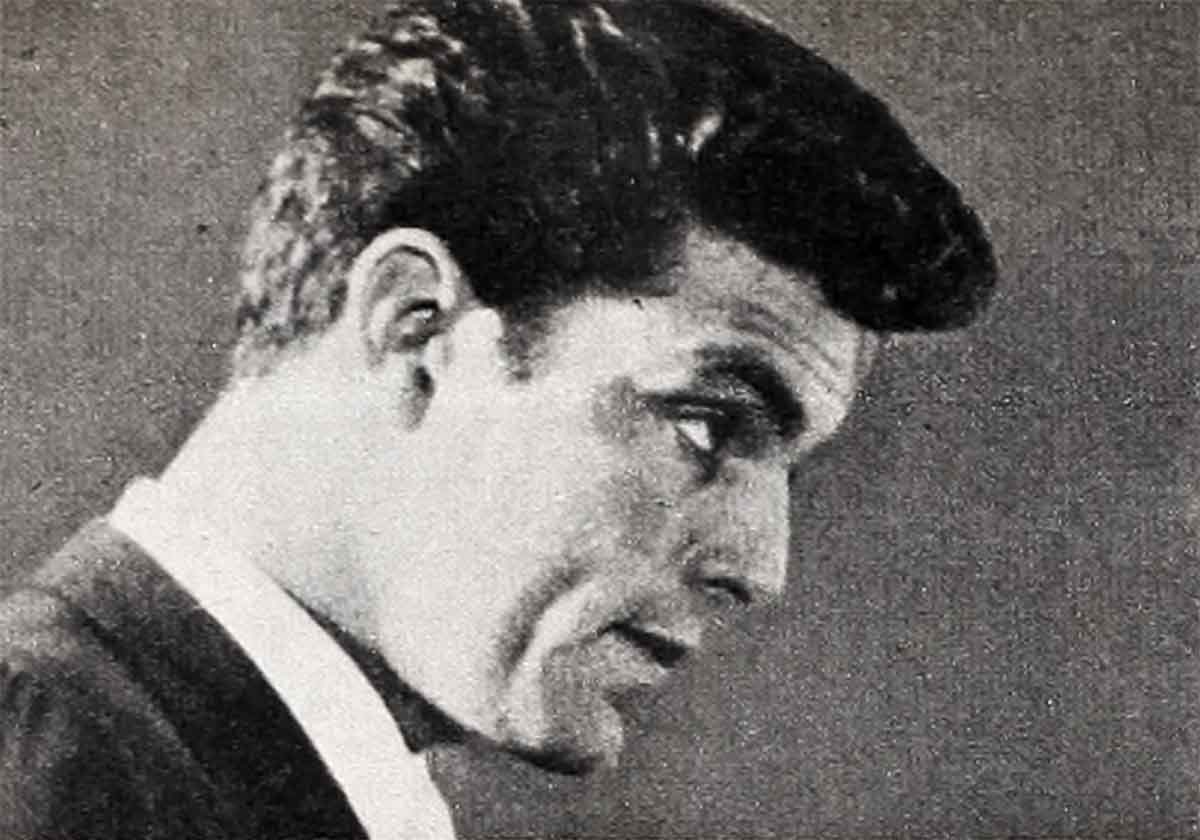

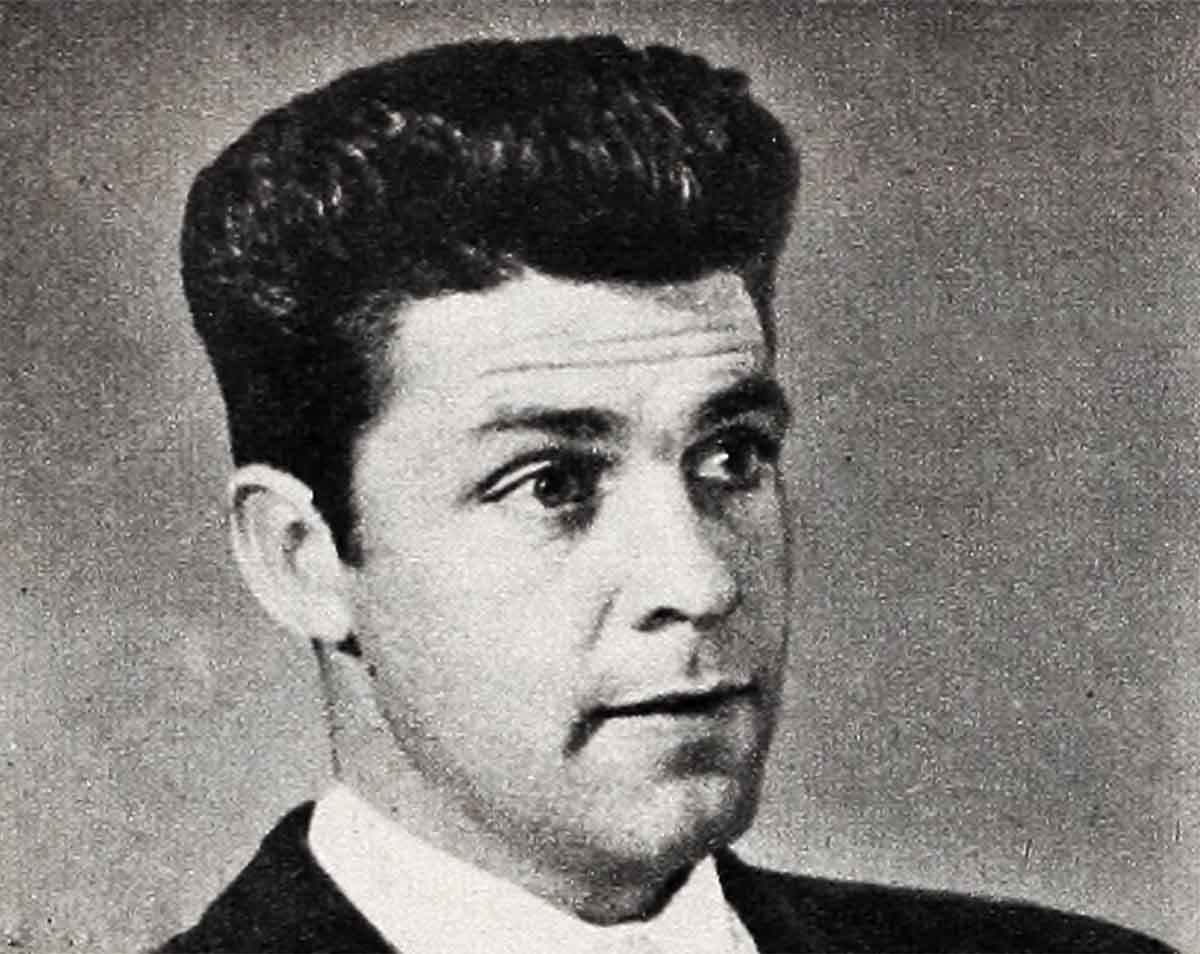

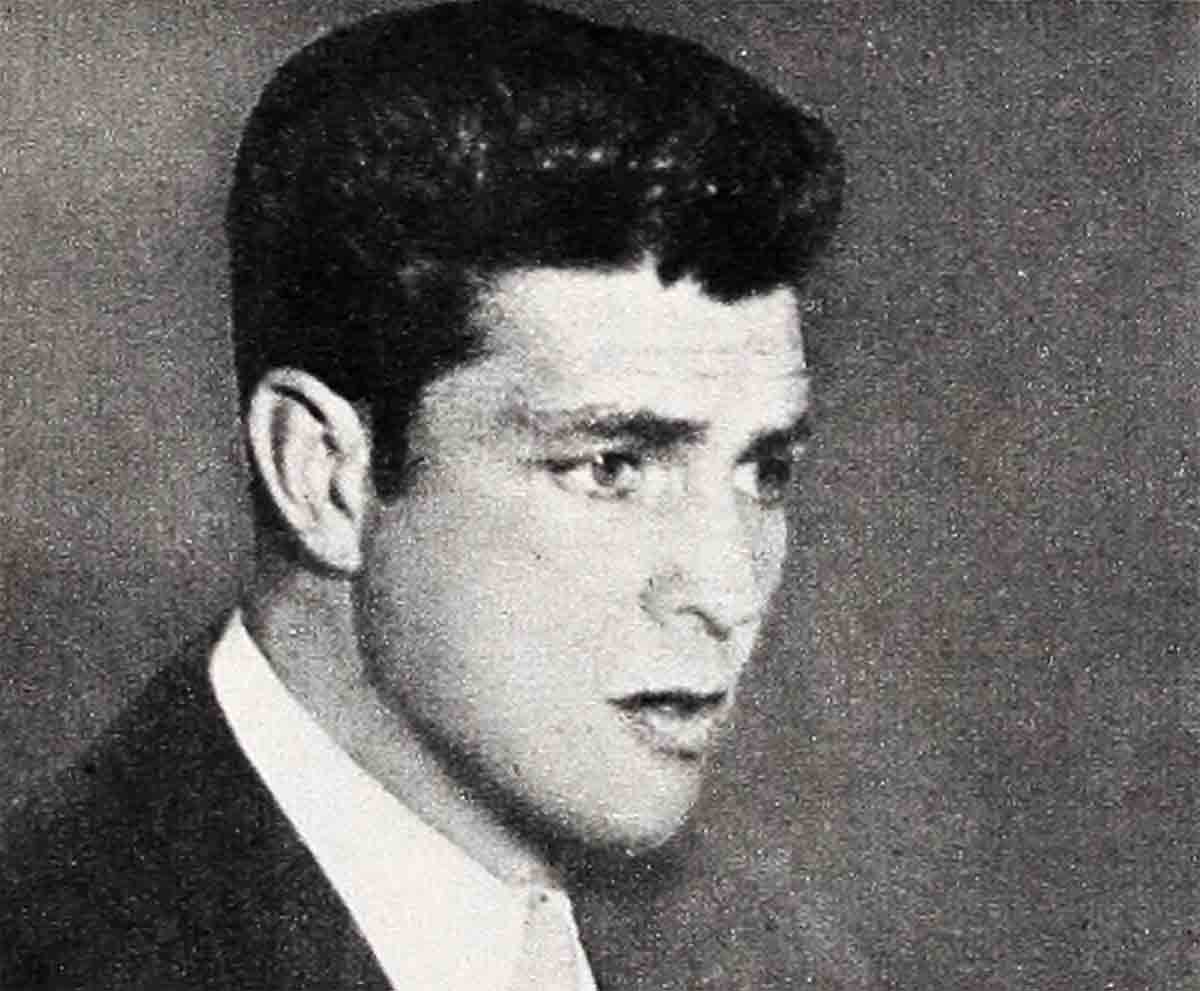

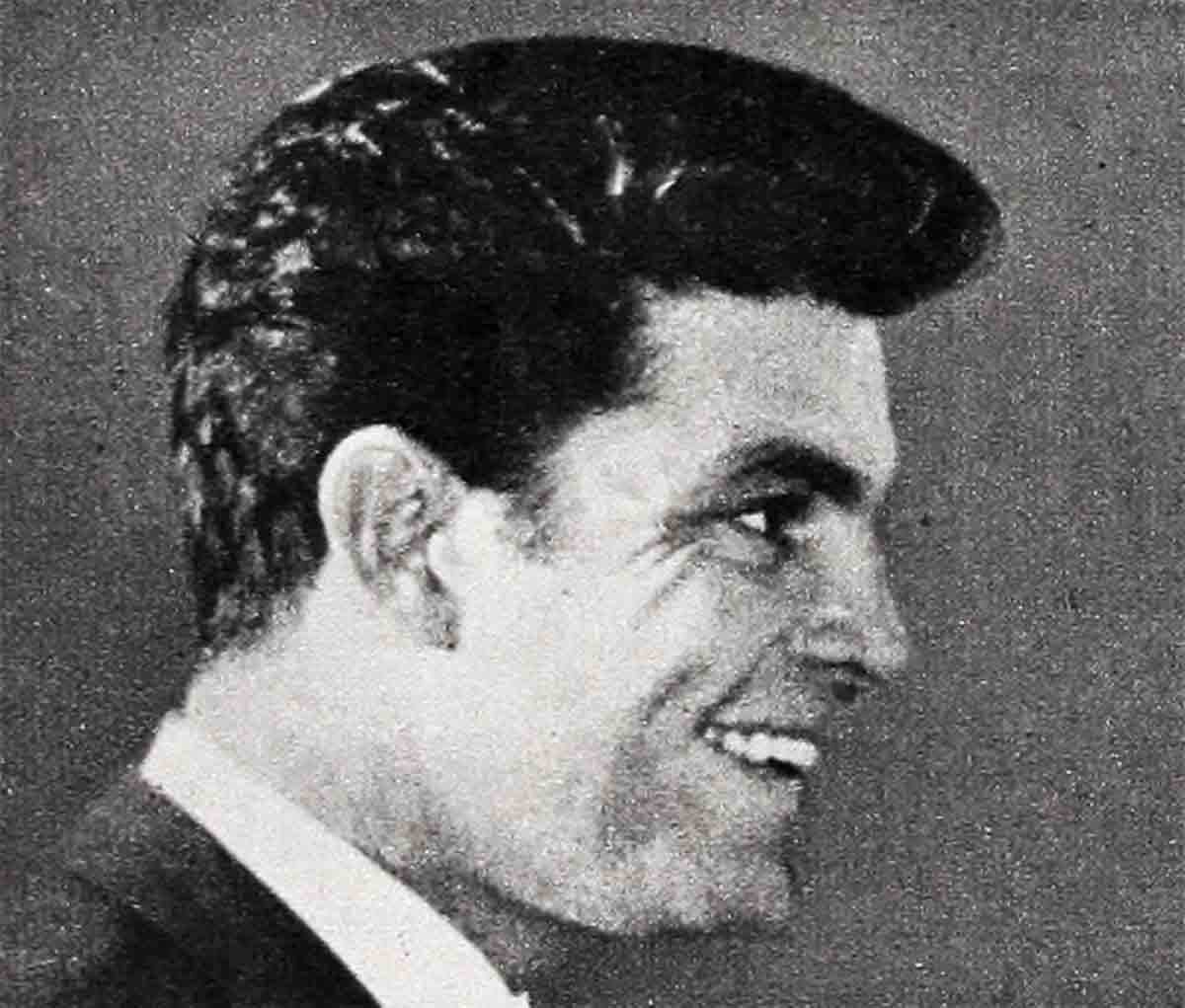

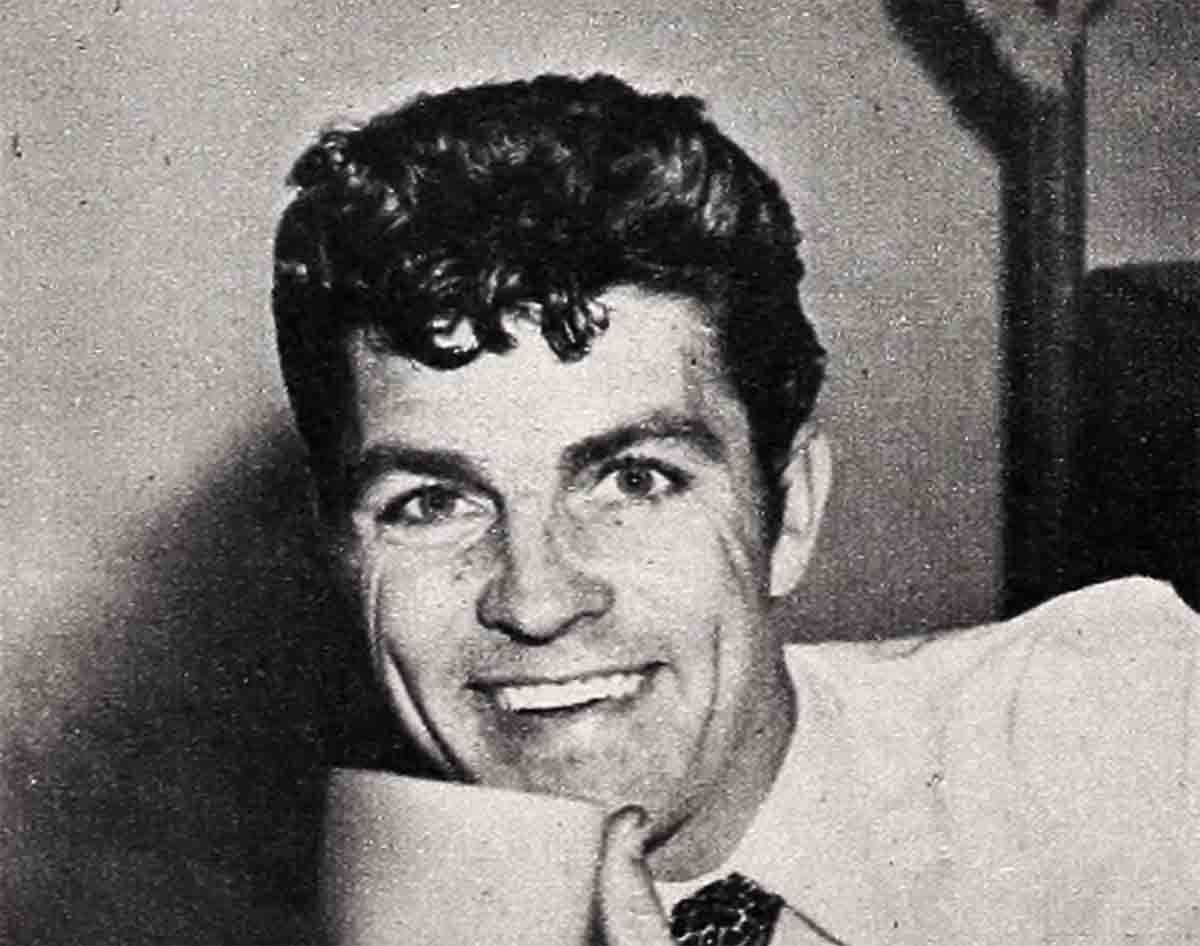

Father’s Day—Dale Robertson

THE PHONE RANG on the Erie Canal set on the back lot at Twentieth Century-Fox Studios just before four o’clock on the afternoon of last July 10, and the assistant director scurried over a vast tangle of cables to pick it up. “Yeah . . . yeah,” he said excitedly, “that’s just great! Yeah, I’ll tell him.”

He got back to his microphone in record time and roared for attention. “Bulletin,” he said, “from Good Samaritan Hospital.”

At this point every one of the hundred or so workers on the stage turned to look at Dale Robertson, standing by to go into a love scene with Betty Grable, his wide open Oklahoma face reddening perceptibly under the make-up.

“A girl,” the assistant director’s voice proclaimed, “weight eight pounds, five ounces, 3:42 P.M., mother and’ daughter doing fine.”

“A girl,” Dale repeated in a low, stunned voice. “Rochelle.”

And while the crowd on the set cheered and applauded excitedly, he began to work his way through a network of outstretched congratulating hands to reach the phone. He wanted to find out for himself how Jackie, his “best girl,” was, if indeed their long awaited first baby had arrived safely and everything was all right. After all—“Jackie never got anywhere on time in her life”—this baby was many, many days overdue.

Since eight o’clock that morning, when he had reported at the studio for work after depositing Jacqueline at the hospital, he had been sweating it out, and he wanted to be reassured. He reached the phone stand at last, asked the operator for the number of the hospital and waited. Before the connection could be completed, however, he was summoned back into camera range for the next shot.

For the next two hours he worked. “Singin’, dancin’, lovin’—old triple threat in action.” That’s how Dale described his routine for the rest of that remarkable afternoon.

At six-thirty, though, he was standing over his wife’s hospital bed, trying to make sense out of her anesthetic-fogged mumblings, trying to let her know how glad he was that it was over and that they had a “sweet little baby girl.”

“Have you seen her?” Jacqueline wondered sleepily.

“Yes,” Dale fibbed. (He had come straight to Jackie; she was the one he was worried about.) “She’s wonderful. Big, strong—be riding Black Diamond before you know it.”

The little blue-black race horse—“only fourteen hands high and the sweetest disposition you ever saw”—was the most recent addition to “horse-happy” Dale’s private stable, and had been earmarked as “the kid’s first pony” ever since the Robertsons knew a baby was on the way.

Jackie didn’t pooh-pooh this boast. She didn’t hear it. She was fast asleep. Dale smoothed the tousled hair back from her forehead, tiptoed out of the room, and headed at a canter for the nursery.

“They held up three newborn babies, and I couldn’t tell which was mine,” Dale said later, but nobody believed him. His conversation on the set on ensuing days (accompanied by free cigars) was too liberally sprinkled with proud-father talk:

“You never saw a baby with so much hair—black hair, like her momma’s. . . .

“Just brought her home from the hospital, and the first night she slept right through from one o’clock until seven this morning. Most kids don’t do that till they’re six months old—or a year. . . .

“She’s a real sweet little baby . . . doesn’t cry hardly at all.”

And he was making plans, not just for training Chief and Little Chief, his German shepherds, to guard the little girl, or for educating Black Diamond for his new role as Rochelle’s own horse. (“Maybe when she’s about two we can start her ave to stay right with ’em at that age, though. Kid wouldn’t be strong enough yet to pull up on him.”) Dale was planning for a new kind of life as a family man.

“We’re gonna need a bigger house pretty soon,” he announced a few days after Jackie brought the baby home from the hospital. “But not until the kid gets old enough so I can tell her not to write on the walls. As long as she’s dead set on writin’, she can practice on this house.”

Rochelle is at present ensconced in the “spare room” of the Robertsons’ three-bedroom San Fernando Valley cottage. Dale had painted the walls and furniture blue shortly before the baby arrived, and the new crib and bathinette were also blue.

“Blue is supposed to be for boys,” he concedes. His friends will tell you that Dale confidently expected a boy from the moment his best friend and stand-in, Kit Carson, announced the birth of a bouncing ten-pound son. His son was going to weigh at least ten and a half, Dale predicted, although he. did admit that the Carsons, “the nicest people in the world,” had “a mighty fine big boy.”

The nursery—‘Don’t get fancy, it’s only the spare room,” Dale insists—will remain blue despite the awkward fact that the occupant is Rochelle Robertson and not Cary Scott Robertson. Since “we’re gonna have four or five, if we can,” they’ll stick with the blue and take their chances on the next baby being a son. Rochelle can write on the blue walls, if she insists, with pink crayons.

And she’ll probably get away with more than that. Dale makes a determined attempt to be casual about his new daughter: “Can’t tell much about a kid when she’s so little. Sure, I hold her sometimes, but she’s usually asleep.” Nevertheless, he shows every sign of turning into the type of father who carries a wallet full of photographs and indulges the children scandalously.

Rochelle isn’t going to be any “Hollywood-type” child. Dale has seen too many of these, “turned over to a nurse, and brought in all gussied up to be inspected by their parents for half an hour each day.”

“I don’t approve of nurses,” Dale says flatly. “We had a lady for a couple of weeks after the baby and Jackie came home (real nice lady this one was—my aunt-in-law), but just as soon as Jackie was up and around we let her go and took over ourselves.

“I’ve seen too many of those kids with nurses. Kid grows up and every time it hurts its finger it runs to its nurse instead of to its momma and daddy. I’ve seen it. Friend of mine tells his kid to do something, and the kid goes right on playing until the nurse tells him to do what his daddy says. Not my kid.”

Dale and Jackie are willing and eager to shoulder the full responsibility for Rochelle’s upbringing, though Jackie, in the last few weeks before the baby came, worried a little about her adequacy for the new job.

She had never handled a baby in her life. Of course, she had a fat contingent of willing coaches: her mother, her sister-in-law, who had a baby last spring, and her good friend, Boots Carson, Kit’s wife. Yet Jackie had her moments of anxiety, usually in the middle of the night, wondering if she would ever learn to bathe the wriggling little thing, or change its diapers, or make the formula.

Rochelle’s tardiness of arrival didn’t help. Four whole weeks before the baby came, Jackie had her hospital bag packed and ready. The clean towels were already in place on the bathinette. The new blankets on the crib were turned back.

After two weeks of this, Jackie moved into town to stay with the Carsons. for “the last few days.” The Robertsons’ home is twenty-seven miles from the hospital, and Jacqueline had begun to have visions of having her child in a filling station somewhere along the way, even though “Dale is a wonderful driver, and most babies come in the middle of the night when there’s not much traffic.”

Every day was going to be the day. Jackie had a series of “spurts of energy”—a sure sign. One day she shopped all day for a washing machine. And nothing happened. So she moved back home.

“Maybe you’re never gonna have a baby,” Dale joshed her, but, to tell the truth, he was getting nervous, too. He worked all day at the studio, came home for dinner, played two hours of softball with his Dale Robertson Shamrocks in the evening, and then settled down to look at a few fights on television before turning in. Each night, as he locked up, he’d look at Jackie.

“Feel all right?” he’d ask. Jackie says that she knew he was wishing she didn’t.

It was four o’clock in the morning of the tenth of July when things started to happen. At five-thirty he called the doctor. At six o’clock Jackie was in the hospital labor room and Dale was directed to the Fathers’ Room down the hall. He looked in as he passed by—commiserated with the other waiters—and hurried on. For at eight o’clock Dale had to be on the set, resplendent in sideburns and wedding clothes of the 1850 era for “The Farmer Takes a Wife.”

He shrugged it off with a laugh for his pals in the picture. “My wife is having a baby over in town and I’m here gettin’ married.”

But it was a long, rough day for Dale. For Jackie, too, he is willing to admit.

Anyhow, the next time—when Jackie goes to the hospital to have that baby brother for Rochelle that the whole family wants—any singin’, dancin’, and lovin’ Dale Robertson is booked to do for his employers will just have to wait until the good news comes.

That—you can take Dale’s word for it—is for sure.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952