At Home Abroad—Gene Kelly

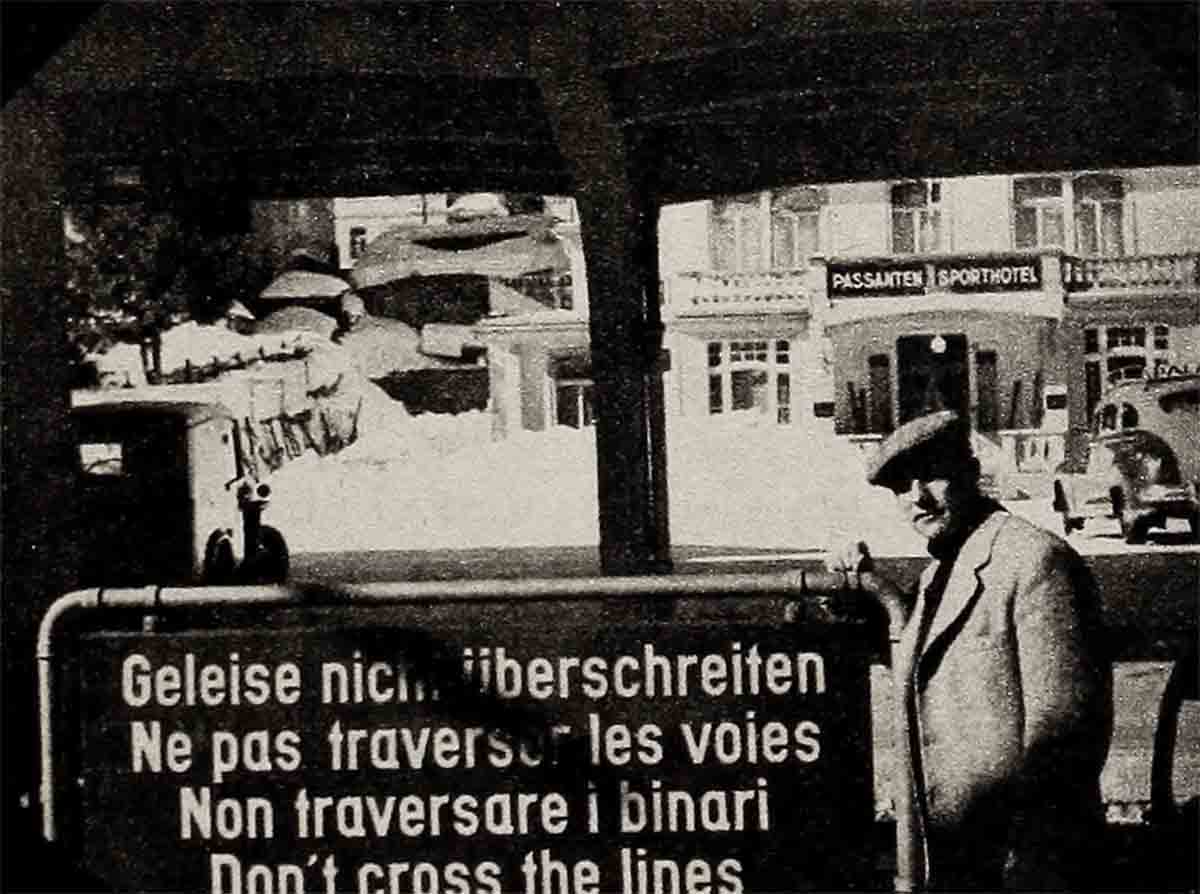

Across the Pont Neuf, one of the smaller bridges that span the Seine in Paris, you find the Place Dauphine, a quiet, respectable, middle-class neighborhood.

On the sixth floor of an old-fashioned apartment house, overlooking this picturesque tree-filled square, Gene Kelly lives with his talented, outspoken, beautiful young wife, Betsy Blair, and their only offspring, a charming, bright-as-a-new-penny ten-year-old girl alliteratively named Kerry.

The Kellys live in a five-room flat sub-leased from a lady who used to reside at the American Embassy, which is why when you ask around the Place Dauphine where Gene Kelly lives, the French children in the neighborhood giggle, do a little dance step for you, then point to the sixth floor and shout, “L’apartment Americain.”

The three Kellys have been living in Europe for more than a year now, and while they’re unusually adaptive and speak French fluently—Betsy and Kerry went to the Berlitz School in Los Angeles—they’re still as American as Main Street.

Like all innocents abroad they hunger for home; and they’re determined to return to Beverly Hills come September of this year.

“I’ve worked and traveled all over the Continent,” Gene says, “France, England, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, all these places have got their strong points, but for day-to-day living, you cant beat the United States, and that goes for life in Pittsburgh as well as Hollywood.”

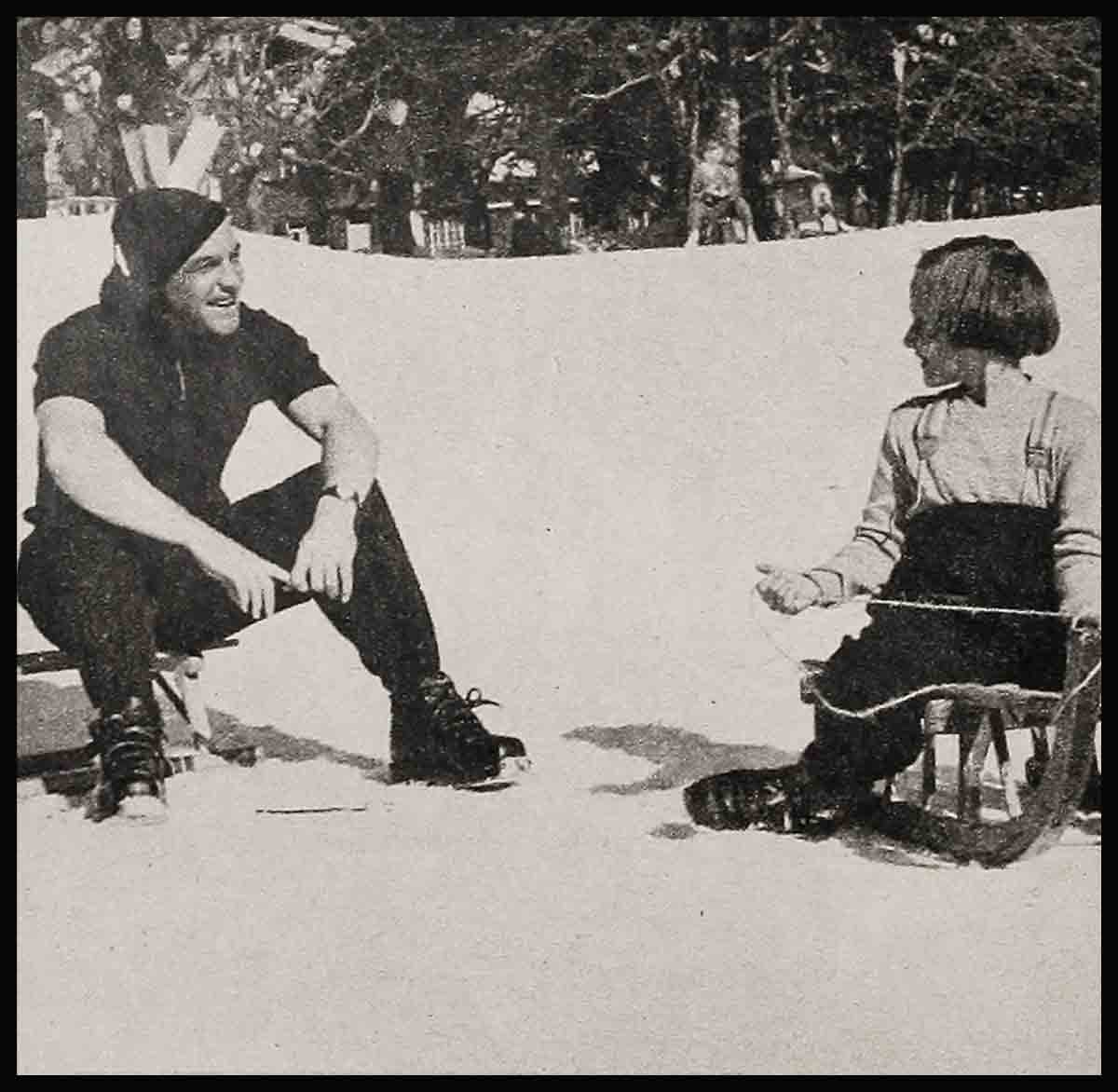

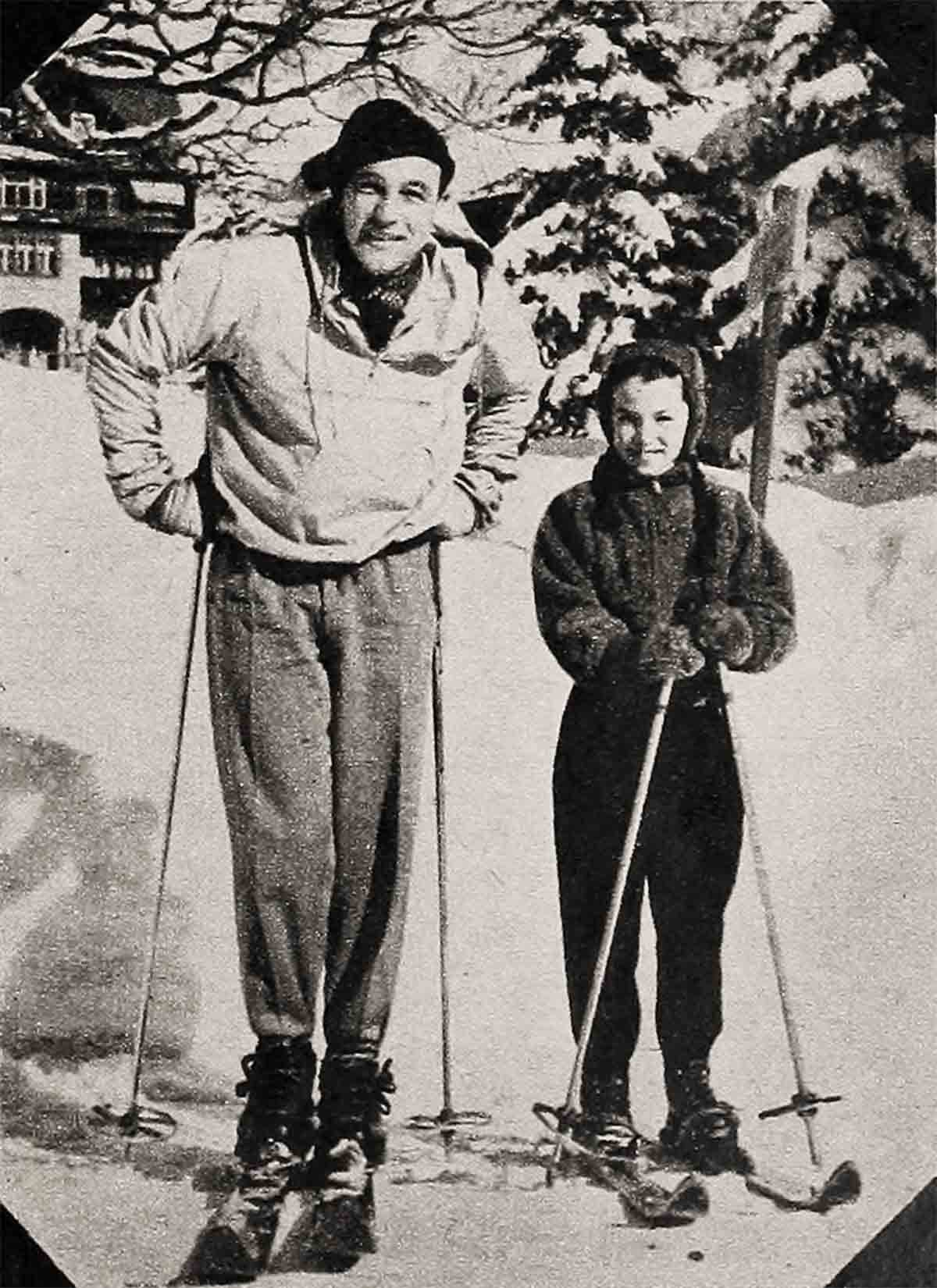

Kerry Kelly, who is her father’s image, feels like that, too. “Daddy was doing a picture in Munich,” she recalls, “when we first came over here, but I never went to school in Germany. I went to school in Paris. It’s called La Petite Ecole. It’s sort of a semi-private school. It’s very nice, and then I went to school in London when Daddy was working on Invitation To The Dance. And in Switzerland I went to a school where you go to class in the morning and ski in the afternoon and, really, that’s the best school of all. But even so, I can’t wait to get back to Beverly Hills.”

By June, 1953, Gene Kelly will have been away from the U. S. for 17 months. In that time he has completed three films, The Devil Makes Three, Invitation To The Dance, a picture in which there is no dialogue, only ballet, and Crest Of The Wave.

In those 17 months, Kelly has been the target for as vicious a gossip campaign as has ever been directed toward any actor.

First, it was said that he and Betsy had separated and were planning to divorce, and second, it is still being said that his patriotism is open to question because, after a year and a half abroad, he does not have to pay any Federal income tax.

Just for the record: Gene and Betsy Kelly have never been happier, and Gene is as honest, patriotic, and law-abiding as any man living. During the last war he volunteered for duty in the Navy and pulled a good long stretch.

But we’ll get to that tax and patriotism question later. First, the matter of his domestic relations.

“I don’t know how those rumors start,” Gene insists, “and I don’t care. They’re not true, and I don’t even want to honor them with any discussion. Ask Betsy for her opinion. She’s got some ideas on the subject.”

Betsy says, “It’s very funny, no kidding. Friends back in Hollywood send us clippings all the time. Gene and I are breaking up, they say. That’s the tenor of most of them. Where these columnists get their information from I don’t know. Probably from returning travelers.

“Geographically, it’s true that Gene and I have been separated, but that’s only because he was working in London, and I was working in Paris or in Italy.

“When we were in London, we were living in Robert Donat’s house, and Gene was working very industriously on Invitation. I tried to get a job, any kind of acting job. After all, Kerry was going to school, and I had a lot of spare time. I read for a part, a good role, in something called Letter From Paris. They liked my audition and said ‘Okay, you’re in.’ Only I couldn’t get a labor permit.

“Just about then, Tola Litvak (Anatole Litvak the director) asked me to come to Paris and work with him as dialogue director and general assistant. He was starting to prepare The Girl On The Via Flaminia, and he needed a couple of assistants to teach the cast English. Sidney Chaplin, Charley’s son, and I luckily got the jobs.

“I came to Paris. Gene and Kerry and Lois (Lois McLelland is Gene’s secretary and a very close family friend) remained behind in London.

“Right there the stories started. Gene and Betsy had each gone their separate ways. It was ridiculous, of course. I flew back to London practically every weekend. Kerry was in school from nine to four every day. It worked out extremely well.

“It so happened that the picture with Litvak took a pretty long time. Tola is a very careful director, you know. Everything has to be just so.

“Eventually the entire cast and crew went down to Nice. Tola insisted that Sidney and I stay in the same hotel with him. He didn’t want us to corrupt the cast. They knew just enough English for the picture, and he didn’t want them to get too good. Someone found out about Tola’s orders that the dialogue directors stay in the same hotel with him, and the again another rumor started.

“Anatole Litvak was going to make Betsy Kelly a big star. He was going to give her the lead in the picture. Lead? I didn’t even get a bit. Anyway the gossip mongers had me coupled with Tola. It was laughable, but that’s how the rumors got back to the States. Supposedly, I was leaving Gene.

“Anyway, by last Christmas, Gene and I were both free, and we took Kerry to Klosters in Switzerland. She stayed there and went to school for a while, and I went to Nice and finished up my work.

“In March, all of us jumped into our Sunbeam Talbot and toured Spain. In May, Gene went back to London to start work on Crest Of The Wave. So any day now you can expect the divorce rumors to start all over again. Kerry and I plan to go skiing, probably in the south of France. near the Alps. Someone will say, ‘Where is your husband?’ And I’ll tell the truth, that he’s working in London. And you’ll see the gossip will begin once more. Just a vicious cycle. Honestly, it gets on Gene’s nerves, but I don’t mind it any more.

“If people knew how hard dancers worked, they’d realize that someone like Gene hasn’t got enough strength or inclination to fool around after a hard day’s work.”

As to the tax setup the Kellys find themselves in, Betsy has a few words on that subject, too, but better to let Gene speak for himself.

First, however, some background. In 1951 the Congress of the United States passed a tax law in which it is stated that any U. S. citizen who remains outside the continental U. S. A. for 18 consecutive months need not pay any income tax.

This law was passed because the Army of the United States was building bases all over the world and was finding it increasingly difficult to secure defense workers.

In order to make the overseas job openings in such uncomfortable countries as Arabia, Greenland, Algeria, and Morocco more enticing, the law was passed, primarily, as an incentive to recruit manpower.

Now it so happens that in 1951, Gene Kelly’s first contract with MGM was scheduled to expire. Kelly’s films had grossed over $75,000,000 for the studio, and Loew’s, Inc. had no intention of letting Kelly go.

In seven previous years the studio had paid him relatively little, especially when one realizes that Gene worked not only as an actor but as a director, choreographer, and writer as well. As a matter of fact, he was regarded by the studio as a one-man unit.

In 1951, Kelly according to Hollywood standards, should have been earning a minimum of $5,000 a week. He was earning less than half that figure. Taxes, expenses, and commissions being what they are, he and Betsy had managed to put aside only a small amount of savings for the proverbial rainy day.

When Gene’s contract expired, he was offered many lucrative deals. He could have picked up $10,000 a week at Las Vegas. He could have shared in the profits of independent productions. He could have gone to another studio as a unit producer.

The executives at Metro knew all this. They knew most of all that they must under no circumstances lose Gene. After all, hadn’t his American In Paris won the Academy Award, the first time in ten long years an MGM film had garnered that honor?

What sort of incentive would keep Kelly at MGM?

One of the bigshots of Loew’s, Inc. had the answer. Congress had just passed a new tax law. A man could work outside of the U. S. A., and all his earned income after 18 months would be tax free.

The proposition was made to MCA, Kelly’s agents. They investigated in detail. They checked all the legal angles. Gene insisted that he would do absolutely nothing that was not 100 per cent legal and above board.

“Look,” he was told, “geologists, oil workers, engineers are going overseas every day in the week under the identical tax setup. Why should you penalize yourself because you’re an actor? MGM has millions abroad in blocked currency. The only way they can use that money is to make pictures in foreign countries. It is no legal sin to make a film in London or in Paris or in Italy.”

Gene Kelly thought it over. He discussed the proposition with Betsy. If he made three or four pictures overseas, would she come along? Would she have any objections? After all, Metro was going to make the pictures, anyway. Betsy said sure, she’d come along.

As it turned out, Gene flew to Europe first. Betsy stayed behind to sublet the house and then, with Kerry and Lois, followed a few months later.

After the Kellys had been in Europe for about six months—and mind you, they are not the first Americans from Hollywood to take advantage of the favorable tax law—an employee of MCA, the Music Corporation of America and the largest talent agency in Hollywood, began pointing out to a prospective client what a wonderful deal his agency had set up for Kelly.

“He’ll have about half a million dollars tax free,” this employee explained, “because we’re on the ball every minute of the day. MCA doesn’t miss a trick.”

In a few weeks the particular actress who had heard this sales talk demanded that her agent obtain for her the same deal. “You dope,” she told him, “if I make films overseas for 18 months, I don’t have to pay taxes. It’s legal, you dummy. It’s part of the new tax laws. Don’t you ever read?”

It wasn’t very long before pretty nearly everyone in Hollywood climbed aboard the 18-months bandwagon. Evelyn Keyes was the first, then Gary Cooper, Ava Gardner, Kirk Douglas, Clark Gable, Claudette Colbert, Alan Ladd, Lana Turner.

It is possible, of course, that some of these stars may not have had the question of taxes in mind when they left the U. S. but then again it’s entirely possible that the tax forgiveness was the main idea.

Because of this Hollywood exodus, Gene Kelly is bearing the brunt of public griping.

It is he who is consistently and erroneously pointed out as the first Hollywood star to take advantage of the tax law. What does he have to say about it?

“I was asked to make motion pictures abroad. The tax advantages were pointed out to me. I’ve made pictures abroad before, even without the 18-months’ tax setup. The law was passed by the Congress. It’s on the books, and it’s proper and legal. I would sooner cut off my right arm than do anything shady.

“Actors don’t have very lengthy careers; that’s particularly true of dancers. You can burn yourself out pretty quickly. In saving some money for my old age and providing for my family, I don’t see anything morally wrong. In the U. S. there’s a 27½ % tax depletion allowance on oil wells, because the Government expects them to run dry. Creative people run dry, too; but you don’t get any depletion allowance on the inevitable slow-ups of age.

“Actors are ordinary human beings. We have the same hopes and fears; only our careers don’t last very long. I’m sorry but I don’t consider it a sin to put some money away for the day I can no longer work.”

The thing to remember about Gene Kelly is that he is essentially a creative artist, a man who dances because of a life force which propels him. He would dance and experiment with the dance whether he was paid peanuts or a palace.

It is safe to say that he has done more to popularize ballet throughout the world than any other dancer in history. To treat him as a “money man” is to defame his character and to detract from his contributions to international cinema.

When the history of the motion picture industry is written, the name of Gene Kelly will stalk boldly through its pages, and only one adjective will do him justice: “great.”

THE END

—BY TOM DANCY

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1953

No Comments