We Belong Together—Ritchie Valens

At 17, RITCHIE VALENS and his friends Buddy Holly, 22, and J.P. (Big Bopper) Richardson, 24, are dead. Yet in the town of Granada Hills, California, Donna Ludwig, his 16-year-old girl-friend, is listening to his latest album . . . and in nearby Pacoima, his mother, Mrs. Concepcion Valenzuela, is also listening . . . and in towns and cities throughout the United States, his friends and fans are listening . . . listening. And for them. all, one song that Ritchie is singing, “We Belong Together,” has a special meaning . . .

In her home at 10861 Paso Robles Avenue, in Granada Hills, California, sixteen-year-old Donna Ludwig sat listening to the phonograph play the last words of “We Belong Together.” “Donna” had always been her favorite. It was their song—Ritchie’s and hers. He had composed it and sang it “just for you honey.” And even when the song had caught on and kids all over the nation were singing it and dancing to it, “Donna” was still their song, hers and Ritchie’s.

But now . . . now . . . Ritchie’s voice filling the living room . . . that familiar, warm, tender voice, singing only for her. Ritchie was dead, yet this living voice and the words made a pledge and a promise: “Yes, we belong together for Eternity.”

Donna switched off the record-player and her eyes seemed to fill with tears. She looked at the gold-framed photograph. She had taken it to James Monroe High School in Sepulveda—in a black tote bag. They had the flag on the school grounds flown at half mast that day and a boy from the high school band had played taps. After school that day, some of the girls had gone to St. John de la Salle Catholic Church and prayed for him. They had lighted some candles for him, too.

“I never forget him,” she said, looking at Ritchie’s photograph.

She walked across the room and slumped down into a chair. She looked at the phonograph for a moment, then back at Ritchie’s picture. Dressed in a simple black sweater and skirt—she had resolved to wear mourning clothes for a week—she thought, “He used to call me kitten.”

She had met Ritchie two-and-a-half years ago at a party, where Ritchie was playing with a small combo. “He wasn’t known then,” she thought. He was somebody you could like right away. He was very nice. Everywhere he went he made friends . . .”

After the party, they had their first date. And as tenth-graders at San Fernando High School, they began to go steady. There were roller-skating parties, drive-in movies, hamburgers-and-Cokes outings. All the kids in school considered Donna and Ritchie out of circulation. They were always together, going steady, a team.

During the tenth grade she had been very serious. But when Ritchie became popular, they began to drift apart. She didn’t want to go with him because the other kids would think she was clinging to a star.

But he kept saying, “Donna, are you going to wait for me?” They were always kidding about marriage. He used to say, “Please wait for me until I’m twenty-five. Then I’ll have a big glass cabinet to hold all my gold records.”

About a year ago they broke up . . . but not really. One night last September, Ritchie called her up on the telephone and they talked maybe an hour and a half.

“Right while we were talking he started making up this song about ‘Donna,’ and it was so . . . well, he began to cry. He read the words:

‘I had a gi-rl, and Don-na was her na-ame,

Since she left me-e, I’ve never been the sa-ame . . .’

“He called me the next night and sang the song to me, and played the guitar. It was wonderful.”

After “Donna” brought Ritchie fame, Donna Ludwig saw much less of Ritchie. He was always on the go, always out on tours, but his voice—on her phonograph, over the radio, and from jukeboxes—was with her all the time.

Then suddenly, as if out of nowhere, Ritchie would be back in town. He’d call Donna right away and she’d go over to his house where he’d throw a party for all his friends. The parties would be given in a small building in back of his mother’s house.

“Then you couldn’t find a place to park anywhere in the neighborhood,” Donna said. All the kids from the north valley would be there. And there would be Ritchie. Right in the middle. And being just Ritchie, just like he’d played at a school party before he was famous.”

Or sometimes they’d just ride through the streets of San Fernando, she and Ritchie in the back seat of a friend’s car, and he’d close his eyes, play his guitar, and sing.

“I suppose he was almost always happy,” Donna said. “And I know he made everybody around him happy, too. He made me happy.”

Donna smiled for a second, a tiny wisp of a smile, and then she went on. “Most of all, I think, he wanted to make sure he could take care of his mother. I think that’s all he really thought about. I know he didn’t care for money for himself. And he never changed a bit, even after he started to make money. He was so proud that he had been able to buy a house for his mother.”

The last time she had heard from Ritchie was about two weeks ago, just before he left on his last tour. He had said, “My mother is so silly—she thinks I’m going to get hurt.” And then once again he said—just like he always said—“Let’s get married when we’re twenty-five. Will you wait for me?”

Donna straightened up in her chair and blinked her eyes. Then she went over to the phonograph, set the needle down carefully in the middle of a record, and gazed at Ritchie’s picture as his voice sang:

“You’re mine,

And we belong together,

Yes, we belong together

For Eternity. . . .”

At the office of Bob Keene, president of Del-Fi Records, who was Ritchie’s business manager as well as his publisher, there were stacks of a new album, simply called “Ritchie Valens,” which was scheduled to be released that very day. Bob was also listening to “We Belong Together.” He looked up and said softly, “To hear the album is to see Ritchie.” Then he flipped off the turntable control.

“When I hear ‘We Belong Together’ or ‘Donna’ or any of these other songs now, it just makes me want to cry,” Bob said. “But that’s not what Ritchie would have wanted. No morbidity. He must be remembered, and never forgotten. But without tears.”

The first time Bob had seen Ritchie had been May 13th, on Ritchie’s seventeenth birthday, a day Ritchie had selected “just for luck.” He came to Bob’s office and, in half an hour, he put on tape everything he’d ever composed. He’d never do the same song the same way twice. His attitude was like one of the records he made eventually, “Come On, Let’s Go.” He wanted to “Come On, Let’s Go” on everything. That record sold 250,000 copies.

Bob shook his head sadly. “He was such a great kid. . . . You know, just a couple of weeks ago Ritchie was in New York. He was staying with Carl Bloomberg at Allied Distributing. Carl had four little girls. And the girls wanted Ritchie to sing at their school.

“Ritchie had only a couple of hours before plane time. But he sent all the baggage on to the airport. And he went all the way out to their school in Hazel, New Jersey, just to sing for those kids. That’s the kind of guy he was.”

As Bob talked it became clear that he felt as if he had lost his own son, not just a singer he happened to have under contract. He recalled the time he had toured with Ritchie throughout the country, when Ritchie was introducing his own song, “Come On, Let’s Go.” “I remember how he would sit up in his bed in a hotel room, long after the show was over,” Bob said. “And he’d softly strum his guitar and sing Mexican folk songs. I told him, ‘Ritchie, we’ve got to record those songs. They’re beautiful.’

“And do you know what he told me? He said, ‘Bob, I’ll never record these songs. These are the songs of my people. I don’t want to make money out of them.’ ”

Bob got up from behind his large desk and walked over to the turntable. He turned up the volume and Ritchie’s voice, singing “La Bamba,” filled the office. Bob looked out of the window at the crowds crossing the street at Hollywood and Vine, shook his head, and repeated softly, “He was such a great kid . . . such a great kid.”

There was no music at the house of Ritchie’s mother, Mrs. Concepcion Valenzuela, at 13428 Remmington Street, in Pacoima, California, in the house that Ritchie had bought especially for her. Shades were drawn on the windows that were bordered beneath by rows of holly bushes. And although the sun was shining brightly, a shadow had fallen across the single turquoise shutter at the sheltered entrance way of the pink stucco house

The street was choked with cars. Hundreds of youngsters lined both sides of the street, standing clustered in hushed and silent groups. As soon as one group left the house of mourning another group of a dozen or more would move quietly forward and enter.

There were students from all of the junior high schools and high schools from the northern portion of San Fernando Valley. There were others from more distant parts of Los Angeles. And there were neighbors from up and down the street and around the corner.

Inside the house was Mrs. Concepcion Valenzuela, Ritchie’s mother. Her face was heavy with sorrow, but there was an immense dignity, a courage in her bearing that showed she had met and coped with death.

The young people passed before her to pay their respects.

“Lo ciento mucho.”

“I was so proud of him. I am so proud of him,” Ritchie’s mother said.

She remembered Ritchie as a little boy. “When he was such a little boy, only four years old . . . and he had a toy guitar. He used to drag it around the floor behind him . . .

“He was always singing and playing. He had the music in him,” she went on. Then her eyes misted as if she were seeing him again, as a toddler there on a living-room floor.

Or perhaps she was remembering Joseph Valenzuela, Ritchie’s father, who had died in 1951 from diabetes—but not before he had proudly told his wife and neighbors that his ten-year-old son would someday be a fine musician. For it was his father who was the first to give him music, not the insistant rhythm of rock ’n’ roll, but the exciting melodies of the Latin heritage they both shared. On his guitar, Joseph Valenzuela would pluck out the bright chords of the samba and the rhumba, and his round-faced, saucer-eyed, curly-haired son would sing along with him, making up his own words when he didn’t know the right ones. And sometimes he’d accompany his dad on the harmonica, or on his little toy guitar.

There was the day, when Ritchie was only six, that his mother and father had come out of the dime store to find him surrounded by a big crowd. Scared half to death, they pushed though to find him playing his harmonica while his dog, Bondy, howled. This was Ritchie’s first public appearance, although the dog was definitely the star!

Things were rough after Ritchie’s father died. It was hard to make ends meet on the $140-a-month pension he had left. Mrs. Valenzuela married again and then divorced. She hired out as a housekeeper to help provide for her family.

One day in January, 1957, when Ritchie should have been in Pacoima Junior High, he went to his grandfather’s funeral instead. While he was away, a transport plane collided with a Navy plane and the transport plunged onto the schoolground, killing the crew and several of Ritchie’s playmates, kids with whom he’d have been fooling around if he hadn’t been at the funeral.

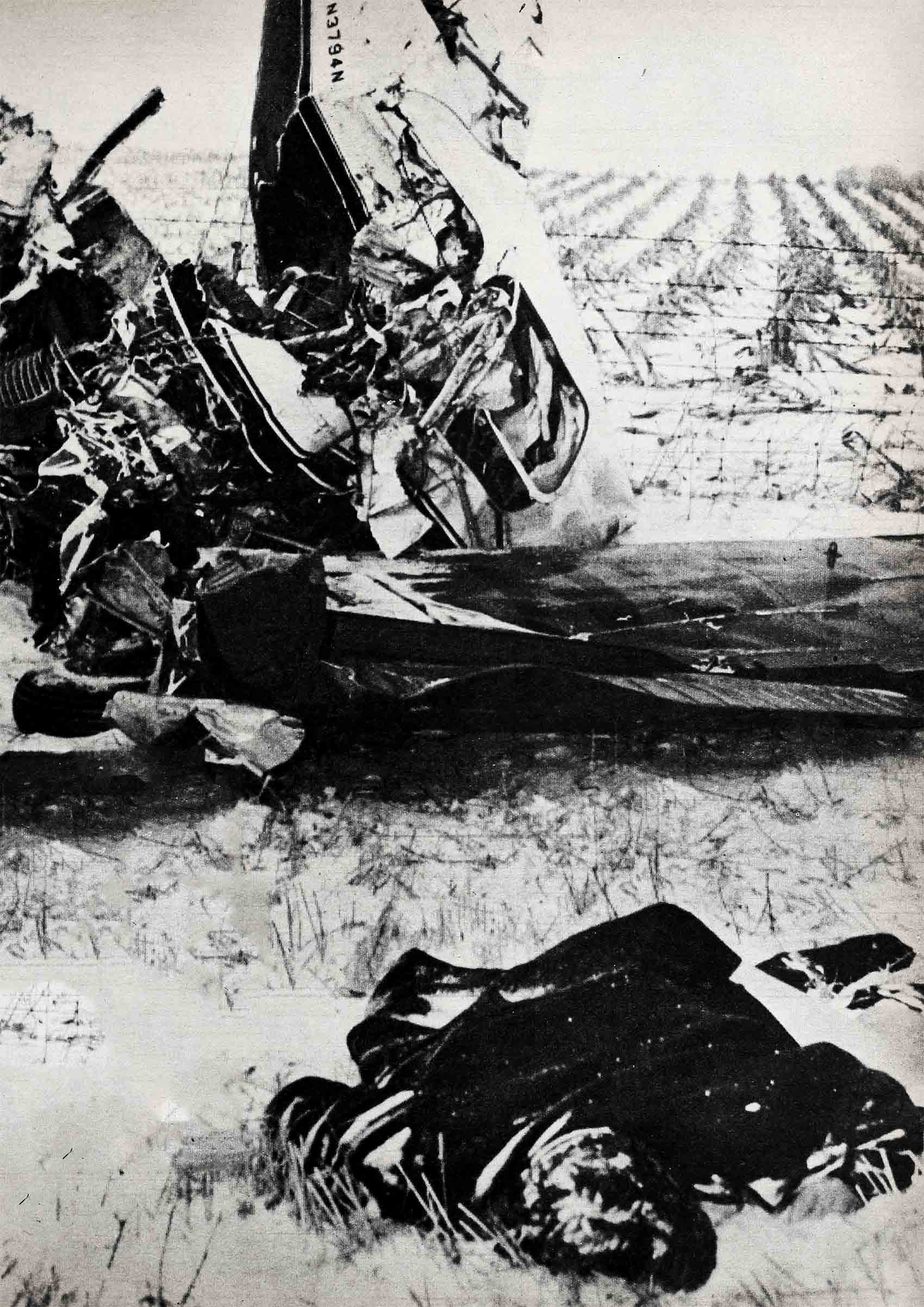

From then on Ritchie had a fear of airplanes. His sister-in-law, Mrs. Ernestine Reyes, of 13812 Judd Street, Pacoima, had driven him to the airport two weeks before, at the start of his public appearance tour which was to end in tragedy. She had told Ritchie’s mother, on her return home, that he had said he wished he didn’t have to fly.

Mrs. Valenzuela brushed at a strand of hair, greying at the ends. “There hasn’t been enough time,” she said. “He wanted to take me on a vacation. He called me from Hawaii when he was there. He wanted me to go there with him on a vacation . . .

“No, there hasn’t been enough time. We had so many places to go . . .”

Then she spoke of the school assemblies Ritchie used to play and sing at, and of his first big appearance at the Pacoima American Legion Hall—the appearance that really launched his career.

In January, 1958, the $65 mortgage payment came due on the Valenzuela family’s squat little clapboard house at 13327 Gain Street. Ritchie’s mother didn’t pay it; instead she called the Legion Hall, and they rented the hall to her for one night for $57—including a cop and the janitor. . . . “He could sing so well, so beautifully,” she remembered. “I wanted him to have a chance and he wanted it, too.”

Well, it seemed that the people of Pacoima wanted to hear Ritchie, too. They paid $2 a couple and $1.25 stag to listen and dance to the music of Ritchie and his combo, “The Silhouettes,” and the Valenzuela family made a profit of $125. Ritchie’s mother took tickets and their next-door neighbor, Angela Hernandez, checked coats and sold soda pop. And when Ritchie would sing—not just rock ’n’ roll but also the sambas and rhumbas his dad had once taught him and the Mexican folk songs his mother had sung to him when he was a boy—the couples stopped dancing and crowded around the bandstand to listen.

There were more dances—two, three, four—all successful, and the printer who printed the dance tickets—someone named Douglas . . . Mrs. Valenzuela couldn’t remember his full name—suggested to her that Ritchie go see Bob Keene, of Del-Fi Records.

With his first recording, Ritchie was on the way up. Overnight, there were engagements all over California. Then came Canada, Honolulu, New York.

And a few weeks before Christmas in 1958, he made the down payment on the pretty pink stucco house on Remmington Street, and the whole family—mother, Connie, 8, Irma, 6, Mario, 2, and Ritchie, moved in.

Mrs. Valenzuela’s voice broke for a moment and then she went on. A few days before the crash Ritchie had called her from some place in the Midwest. “Mom,” he’d said, “it’s like an iceberg here. I sure wish I was back in Pacoima.”

“Is there anything else I can tell you?” Ritchie’s mother asked.

There was nothing else.

She turned away, walked slowly from the living room. At the door to the bedroom at the back of the house, she turned for a moment and said, “He was a praying boy. He was always a religious boy. He always used to go to the church and light candles.” Then she closed the door gently behind her.

A cousin, Mrs. Vera Villafana, had prepared coffee and cakes for the friends of Ritchie who had come to comfort his mother. She said that the funeral services for Ritchie would be held at St. Ferdinand’s Church in San Fernando, and that he would be buried in the cemetery of San Fernando Mission.

Outside of the house, the sun was still shining brightly. Across the street, a car radio was playing softly. A few girls and fellows were standing around the car, listening. It was playing “We Belong Together.” One of the girls said, “Why did it have to happen to him? He was such a great guy?”

Why did it have to happen to Ritchie? This is what the fellows and girls were asking at the Dick Clark Show the day after Ritchie died. And Dick himself was so broken up that he could hardly talk about the tragedy. For it was on one of his shows, on October 6, 1958, that Ritchie had really clicked when he sang “Come On, Let’s Go.”

Why did it have to happen to Ritchie? That’s what the youngsters asked each other over and over again at Alan Freed’s Big Beat session on the afternoon following the tragedy. Alan himself sat in his office before he was to go on the air, just staring at the ceiling. “They were great kids,” he said, “great kids. The Bopper, Buddy, and Ritchie. The best.”

Then he looked at a speck of dirt on his desk blotter and ground it with his hand.

“That Buddy Holly,” he said, “we toured together for forty-four days. He was a bug for flying. Ritchie hated it. The Bopper just slept and didn’t care one way or the other. But Buddy—if you tied two orange crates together, put a wing on it, and said it would fly, he’d climb in and take off. He always wanted to get someplace ahead of the others.

“Crazy, isn’t it, that his new hit is called ‘It Doesn’t Matter Any More.’ I know it matters to me and to all those kids who loved him . . . and to his wife, Maria Elena. You know he’s been married less than six months.”

Alan went on. “That Bopper, he is something. See, I keep saying is instead of was. I can’t believe he’s gone. Not that happy, happy guy. I once asked him why he left his safe, sane job as a deejay in Texas to go on tour, and he answered, ‘Cause it’s a ball. ’Cause I’m getting to see the country. I’m a traveling salesman. Im selling “Chantilly Lace.” ’ A marvelous, mad guy.”

He got up, walked slowly around his desk, and then sat down again. He took out a handkerchief and wiped the smudged dirt off his hand.

“The Bopper wasn’t very religious—in fact I never knew his religion—but I know that he once went to church with Ritchie Valens. It happened last Christmas. The Bopper and Ritchie were both on my Loew’s State Christmas show in New York. Ritchie had just bought his mother a house and he hated being away from her at Christmas. Sure, he found New York exciting. But he was also homesick. He’d walk around and stare at the buildings and then come running back to his hotel. It was too much for him.

“Well, on the day before Christmas he kept talking about his mother and how much he missed her. And he said he was going to Midnight Mass to say a special prayer for her. He asked the Bopper if he wanted to go along. And I never saw anyone so pleased as the Bopper was. I guess the Bopper was homesick himself. Anyway, off they went to the church.”

A page stuck his head in the office. “You’re on, Mr. Freed,” he said.

When Alan walked into the television studio, the boys and girls flocked over to the man who had known Buddy, Ritchie, and the Bopper so well. Some of them were crying and he talked quietly, soothingly to them.

On the show itself, Alan didn’t play any of their records. “This isn’t the time for that,” he said. But he asked for a minute of silent prayer in memory of the three boys. And then Roy Hamilton, in a tribute to Buddy, the Bopper, and Ritchie sang “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” And then the show was over.

Back in his office, Alan answered the telephone. He talked for a few minutes and then put it down. “It’s crazy,” he said. “I just learned they took that plane instead of the bus in order to save some time. For what? Buddy wanted to get a suit cleaned. Ritchie wanted a haircut. And the Bopper just wanted to get some sleep. Said he never could really sleep on a bus. And Ritchie . . . Ritchie flipped a coin with someone else to see who would get the fourth seat on the chartered plane. Ritchie called ‘Heads’ and it came up heads. And he said, ‘What do you know? This is the first time I’ve ever won.’ ”

The phone rang again and Alan answered. “That was my daughter,” he said after he hung up, “my daughter, Alana. She’s thirteen. She can’t stop crying. Just before our Christmas show—the one I told you about, the one the Bopper and Ritchie were both on—she broke her arm. And Ritchie signed her cast. She’s kept it ever since. She can hardly talk. I understand.

“I guess I got to know Ritchie best when we made our movie on the coast, ‘Go, Johnny, Go.’ His only comment when he saw the screening was ‘I’m not much good but I hope my mother will like me.’ That’s the sort of fellow he was.”

Alan went over to the record player and clicked a switch. He pulled an album out of the pile on the floor, slipped out a record, and put it on. The voice of Ritchie Valens—strong, young, alive—sang out:

“You’re mine,

And we belong together,

Yes, we belong together

For Eternity . . .”

THE END

—BY JIM HOFFMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1959