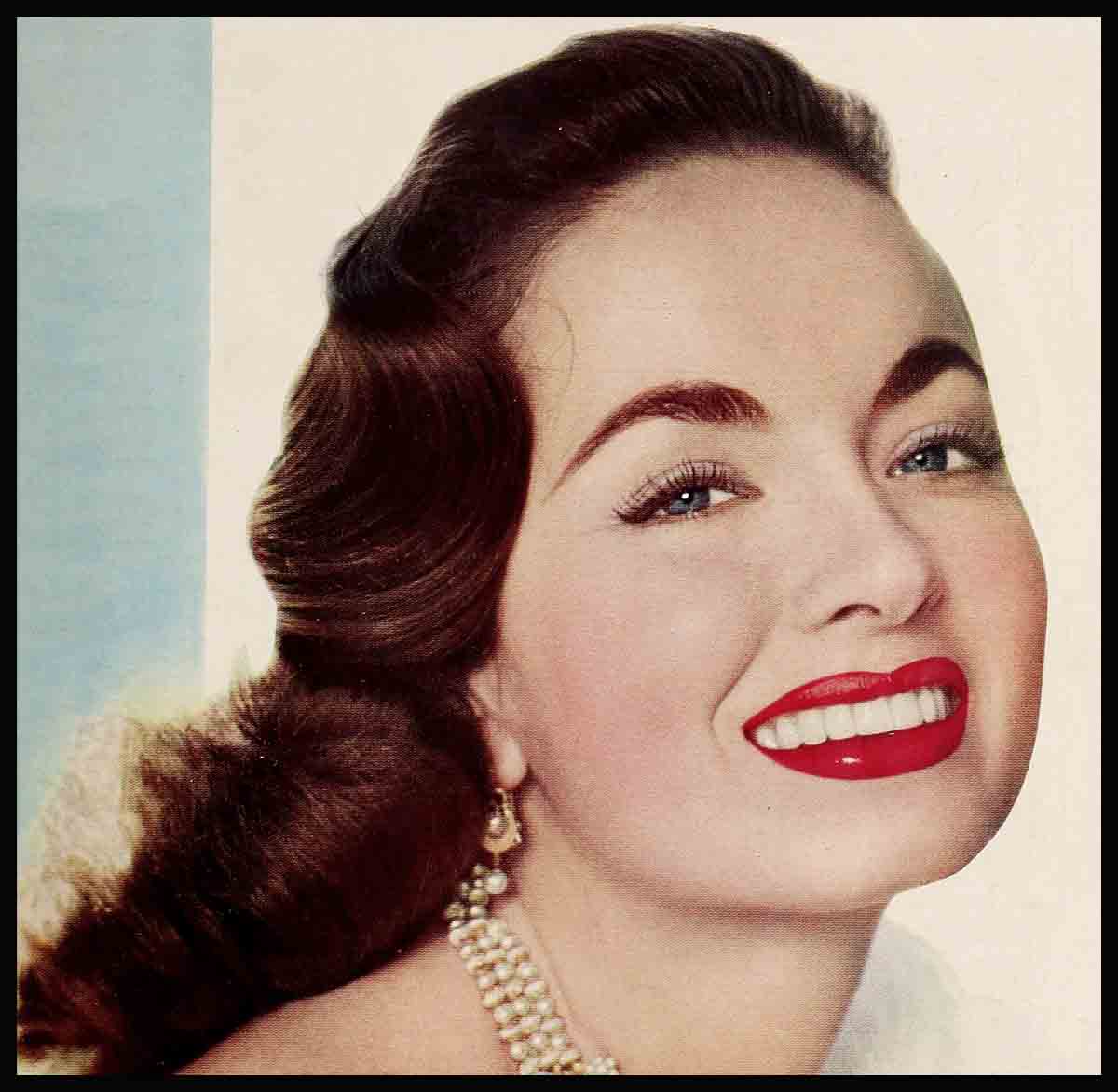

Ann Blyth’s Wedding Day

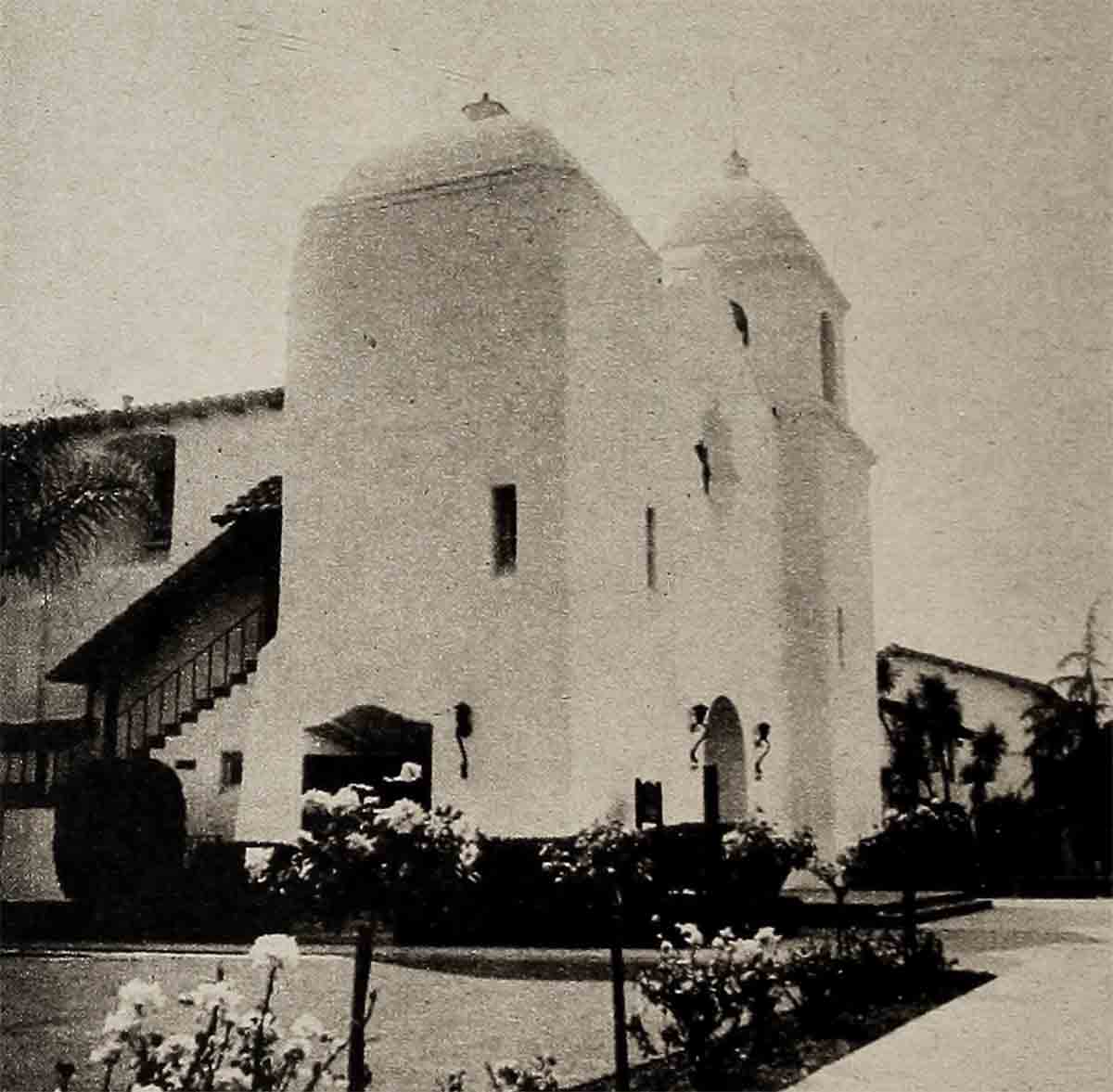

Now if you happen to be reading this on the last Saturday of this month of June it’ll be the moment that Ann Blyth, wearing the wedding dress she dreamed she would, is kneeling before the marriage altar with the boy she prayed she would. At St. Charles, in the San Fernando Valley in California, Ann is becoming the bride of Dr. James V. McNulty. And if you asked her anything about anything else she’d tell you it didn’t matter.

“Ann,” she can only think to herself, “you are marrying in the church of your devotion to the man of your devotion.” And it is true. For though this dark-haired, 24-year-old Irish girl has walked in high places she has been known always for her yearning for simple happiness. She did pray to her St. Anne that there would be someone someday like the tall, young doctor at her side; quietly strong yet gentle like him, and with a ready smile and an understanding way. And she is not above telling you, “My prayers were answered.”

To every girl belongs such a moment as is now taking place at St. Charles—and this is Ann’s to remember forever; solemn with the song of the mass, festive with the flowers and further music, and then, with dear friends and relatives looking on the fateful hush of the ceremony itself.

Yet it is a moment shared by others; not only do those who fill the church know why they have come, those who crowd the street outside for a glimpse of the bride know why they wait. They are caught by a fairy story. Ann Blyth’s folks had no riches when she was born. Hers was a childhood of big city nonentity, of bread and milk in the kitchen, ordinary schooling and, seemingly, limited opportunity. But she had riches to give; in beauty of form and beauty of manner as an actress. And here is the magic that touches this wedding—in this country a colleen can become a queen!

None in the church doubts it when she comes down the aisle on the arm of her Uncle Pat Tobin. She seems to move in the white aura of her veil of diaphanous illusion tulle which is as long as the train of her gown of mousseline de soie over white satin. On her head is Chantilly lace, a bonnet embroidered with pearls. Those whom she passes by closely note the tight bodice of the gown, the long sleeves, and that she carries a rosary and a bouquet of lilies of the valley. If they look at her eyes they know that her soul has risen into them and shines through, luminous with tears and love.

Behind her is her court of bridesmaids and by their names you can recognize some of these, too, as princesses; not hereditary, but risen as Ann in their own personal right through democracy’s processes and public adulation: Marjorie Zimmer, Jeanne Crain, Joan Leslie, Betty Lynn, Jane Withers, Alice Krasiva. The bouffant gown of each is in a lovely shade of blue with matching slippers. Their bodices are also tight with taffeta cumberbunds, their sleeves short but arms covered with long, white gloves. Hach wears a large blue picture hat with taffeta streamers; each carries a little muff of delphiniums. Each has lived close to the bride, has thrilled to her joy, has given showers and helped her plan for the future.

There is another close by who is in pink, her Aunt Cis, wife of Uncle Pat, the two with whom she made her home after her mother’s death several years ago. Uncle Pat, as are all the men, is in striped trousers and morning coat. Dennis Day, Jim’s brother, is his best man; their three brothers, John, Frank and William McNulty, are among the ushers.

This is the moment, the moment which was destined to be the first time Ann met her Jim, nearly three years before, only neither of them knew it then . . . they both have said.

“Isn’t every eligible man a girl meets a potential suitor in her mind?” a reporter had once asked her. “Didn’t you think of Jim that way always?”

She could be thinking of the answer she gave to this question, as she had thought of it many times since. She said she didn’t think so—always. But was it true of her and Jim?

They met at a party and when he left he asked if he could call her. She replied, “Yes,” and he called her four days later. It was not to take her out to dinner, to dance or go to a show, perhaps, but to the christening of a nephew, Dennis Day’s second son. She went and wondered—was this by way of being an introduction to his family?

It was a good thing that she did no more than wonder, that she gave it no greater significance. For in the next two years their work, hers in the studio and on tour, his in his office and the hospital, establishing his medical career, saw them much more apart than together. Then, last fall and winter, they found more time for each other, and a week before Christmas he came over to help her decorate the Christmas tree and seemed not to have his mind on it even when he placed the star on top.

He had dinner with them. Aunt Cis had learned he loved lamb and had made a wonderful roast, yet his plate was practically untouched. Uncle Pat threw questions at him on matters of the day and each seemed to catch Jim’s mind wandering. And when the older folks left them alone and they got started on the tree, Jim had kept hanging the decorations upside down. Something told her then. And she was right . . . but barely! He was half-way out the door that night when he suddenly turned back, the words she wanted so much to hear came tumbling out, and her whole world took on new and great dimensions—he wanted her!

From that second Jim was not the same Jim any more, she was not the same Ann. When he went home that same night he telephoned her, within three minutes it seemed, after he left. He said first that he had just wanted to tell her that he had gotten back safely . . . and she had thought warmly and fondly, “He’s reporting already.” Then, he couldn’t just leave it at that . . . he wanted to talk some more.

“Tell me,” he asked, “did I propose to you when I was there a few minutes ago?”

“Yes, you did,” she said.

“And did you say, ‘Yes?’ ” he pressed on.

“Yes, Jim. I said, “Yes,” she told him.

“Ah!” he sighed with relief. “I just wanted to be sure. That it really happened. That it’s true.”

They went to musicals. They went to concerts. They laughed because in college he had played a saxophone in a band but she had never heard him play. They laughed because he had seen only a few of her pictures and she had far more faithful fans than he.

“How could you stay away from my pictures?” she asked, kidding him.

“Do you go to see the operations I perform?” he came back.

They went to parties. Because Jeanne Crain had teased her about Jim she wanted Jeanne to know about the engagement. “Who was teasing?” asked Jeanne. “I was predicting! I was perfectly sure it would happen.”

His mother had told her she knew Jim was going to propose. “For a week before, I never saw such a one as him around the house,” she said. “So preoccupied he was!”

Now that it had happened all their friends said the same thing. “We could have told you!” And she wished they had.

A bride’s hope must feed on memories and these are the ones that must fill Ann’s mind. The home they bought, the Connecticut-style farmhouse in Toluca Lake. It was raining when she went first to see the house with Uncle Pat who had hunted it up. Yet she loved it and when Jim wanted a description she said, “It’s the kind of house that just reaches out and puts its arms around you.”

But then she was sorry she had said this much because she hadn’t wanted to influence him, and when they went to look at it together she said not another word . . . but just watched him. That was enough. It seemed to her that he thrilled as she had at everything; the slant roof, the wide, inviting stairway that greeted you as you entered, the Dutch fireplace, the warm, yellow kitchen, the den you could see into from way out in the back through picture windows.

They took it. She was a bride not only with a diamond solitaire set in platinum, but with a house to take over and furnish and live in!

They decided they wouldn’t try to buy all they need at one time but instead to pick up pieces slowly, matching and suiting as they went along. But he had nothing to say about the first household article that came her way because it was a gift—a rolling pin with cookie mold attached.

For the first time since she had met Jim he visited her at the studio. She took him to the All The Brothers Were Valiant set at MGM and introduced him to everyone from Bob Taylor and Stewart Granger to her hairdresser, Florence Erickson, and the wardrobe lady, Tommy McCoy. “This is my Jim,” she said. This is how she found herself referring to him—without planning or thinking.

Only a few days before his visit the marriage scene from the picture, in which she and Bob Taylor were wed, had been shot. She had worn not only the engagement ring Jim had given her but his second gift, pearl earrings. Now everyone kidded Bob Taylor on his role, telling him that he had been only the stand-in for the real thing.

Well, here before the altar with Jim this is the real thing. Nothing else matters. Only this moment when he takes her hand in his and places the marriage band on her finger to mark the end of loneliness; this moment, the first of many wonderful ones that will stir her heart.

THE END

—BY THELMA MCGILL

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1953