Sybil Burton And The Wild Ones

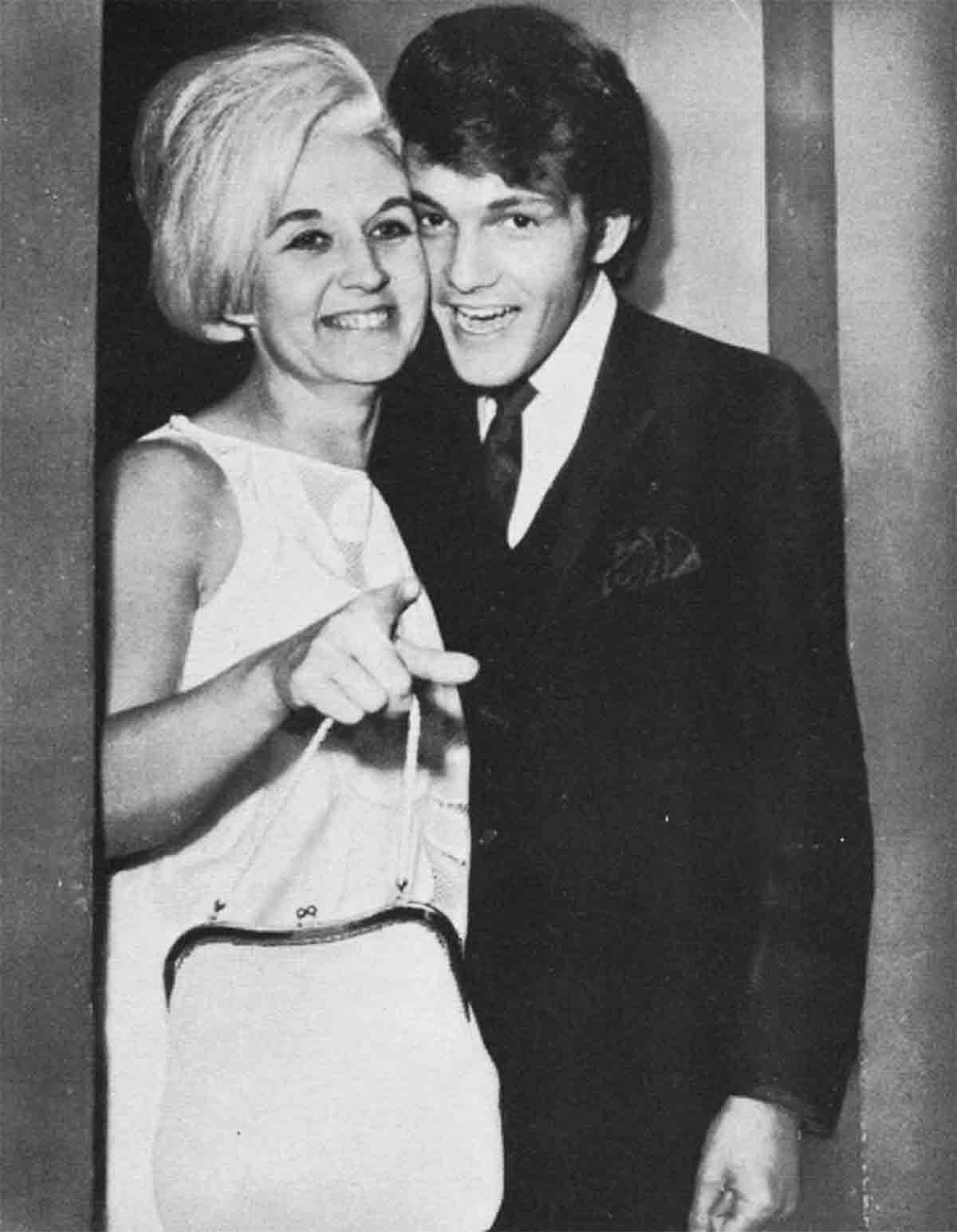

Next time you’re in New York and you’re trying to find where the action is, don’t waste your time in Greenwich Village. Nowadays, the Village is strietly for the squares. The “In” crowd heads for the cool scene up on: 54th street. just a few blocks east of Broadway, in the neon maze of midtown Manhattan. This is where the real swingers hang out—bluebloods of the hip and haughty set who disembark from expensive limousines and foreign sports cars to queue up impatiently for their nightly ration of grog and kicks at a wild discotheque called “Arthur.” Managed by Sybil Burton Christopher, a white-maned. 36-year-old Welsh expatriate who was known as “the second woman” in the Richard Burton-Elizabeth Taylor affair. Sybil, in case you don’t read the gossip columns, is now married to a 24-year-old American-type Beatle named Jordan Christopher, the leader of The Wild Ones who were hired to make lusty music for “Arthur’s” devotees.

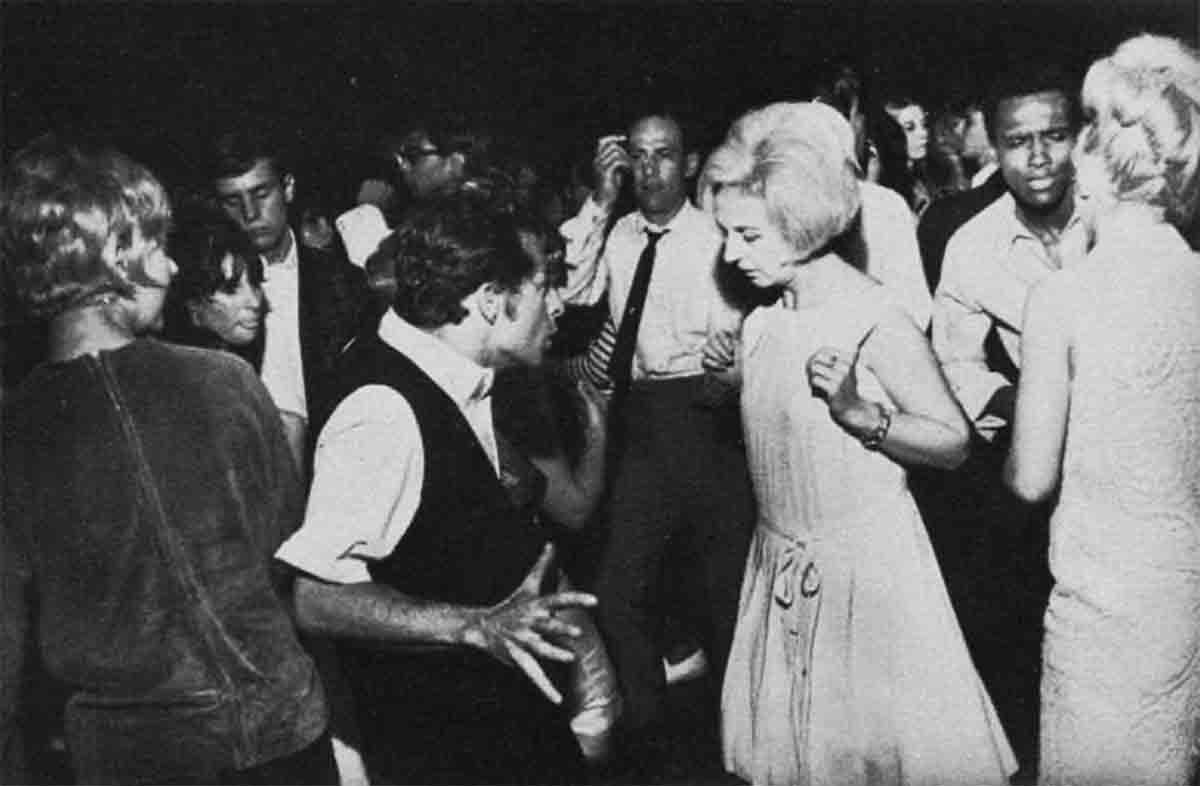

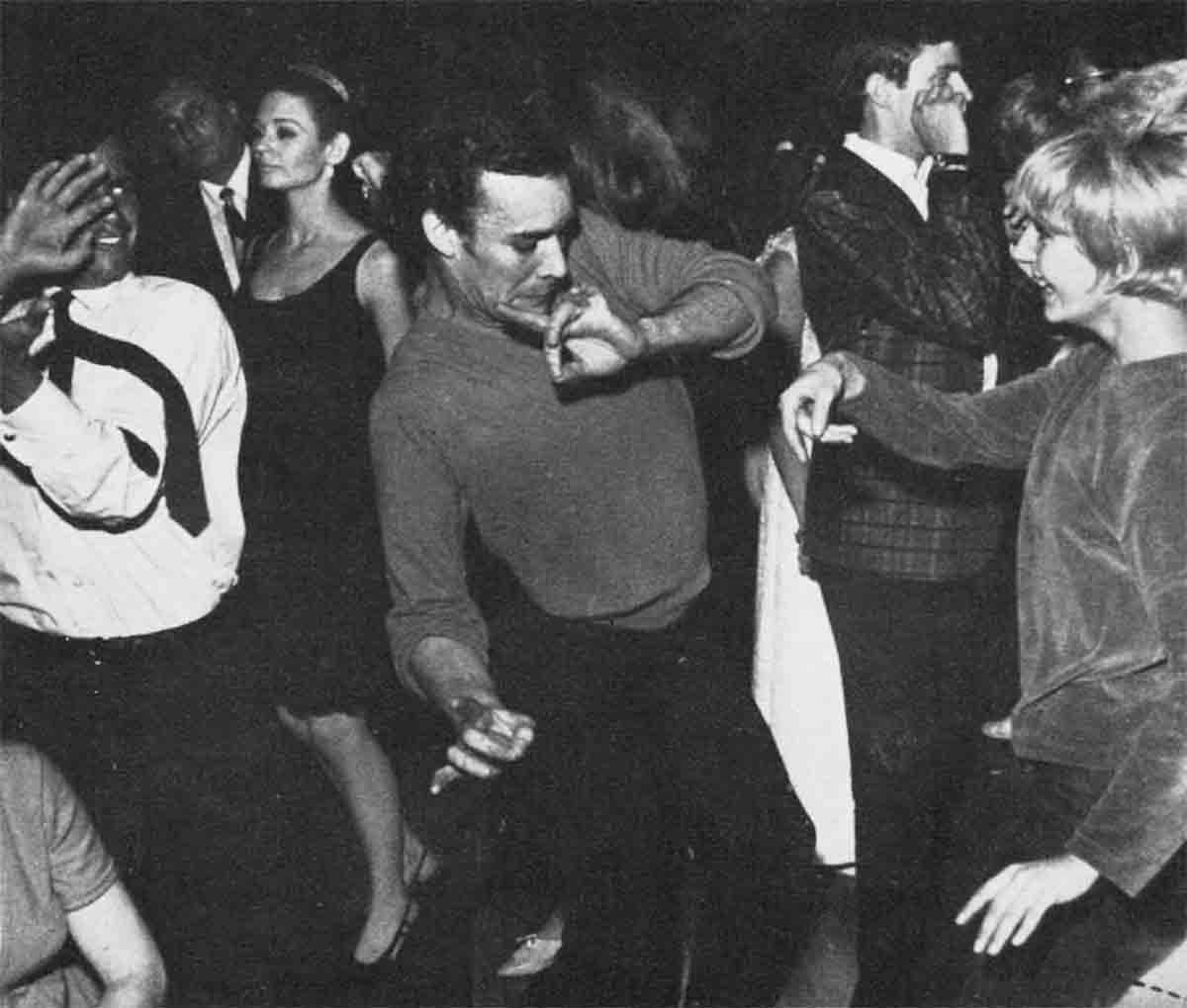

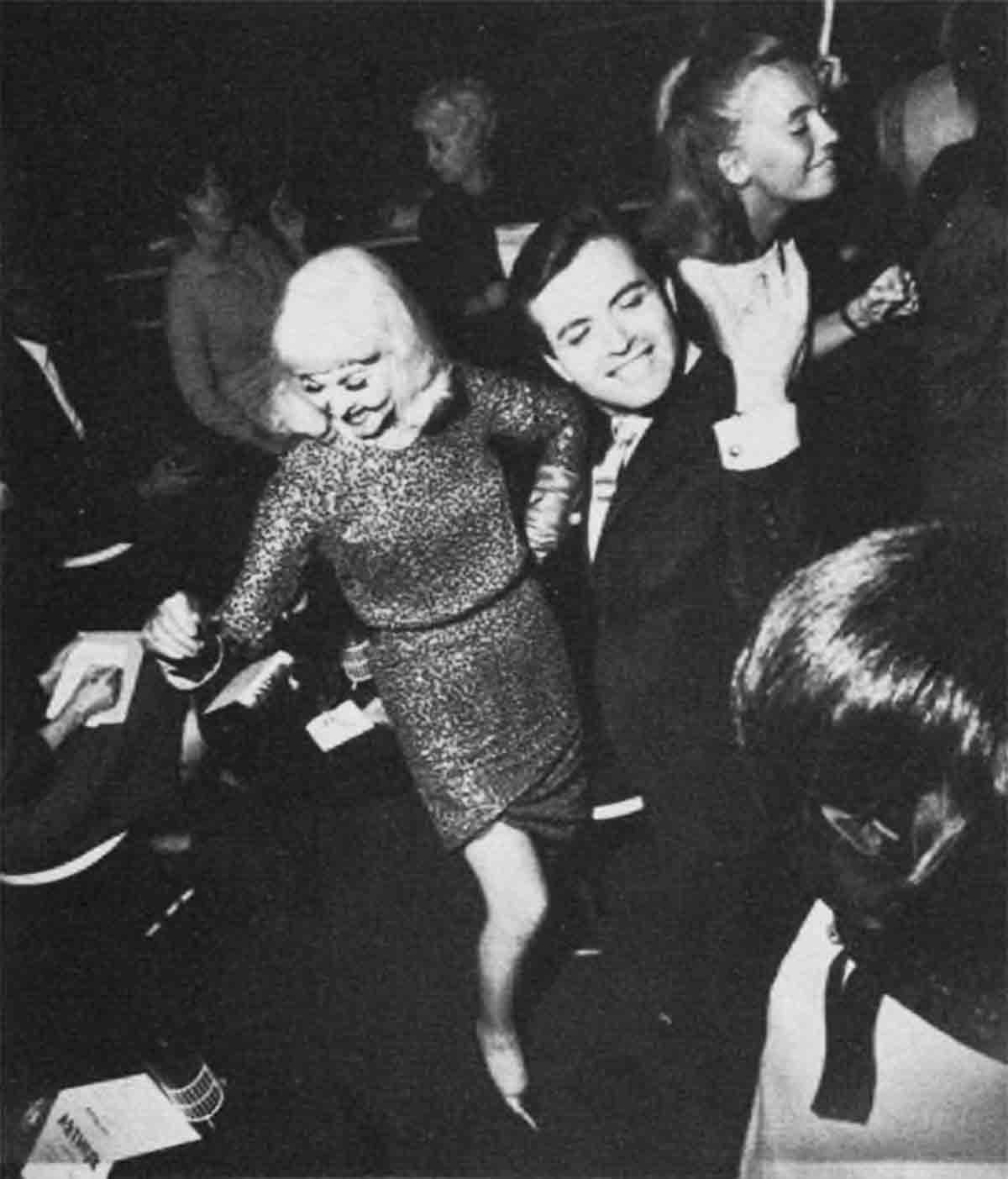

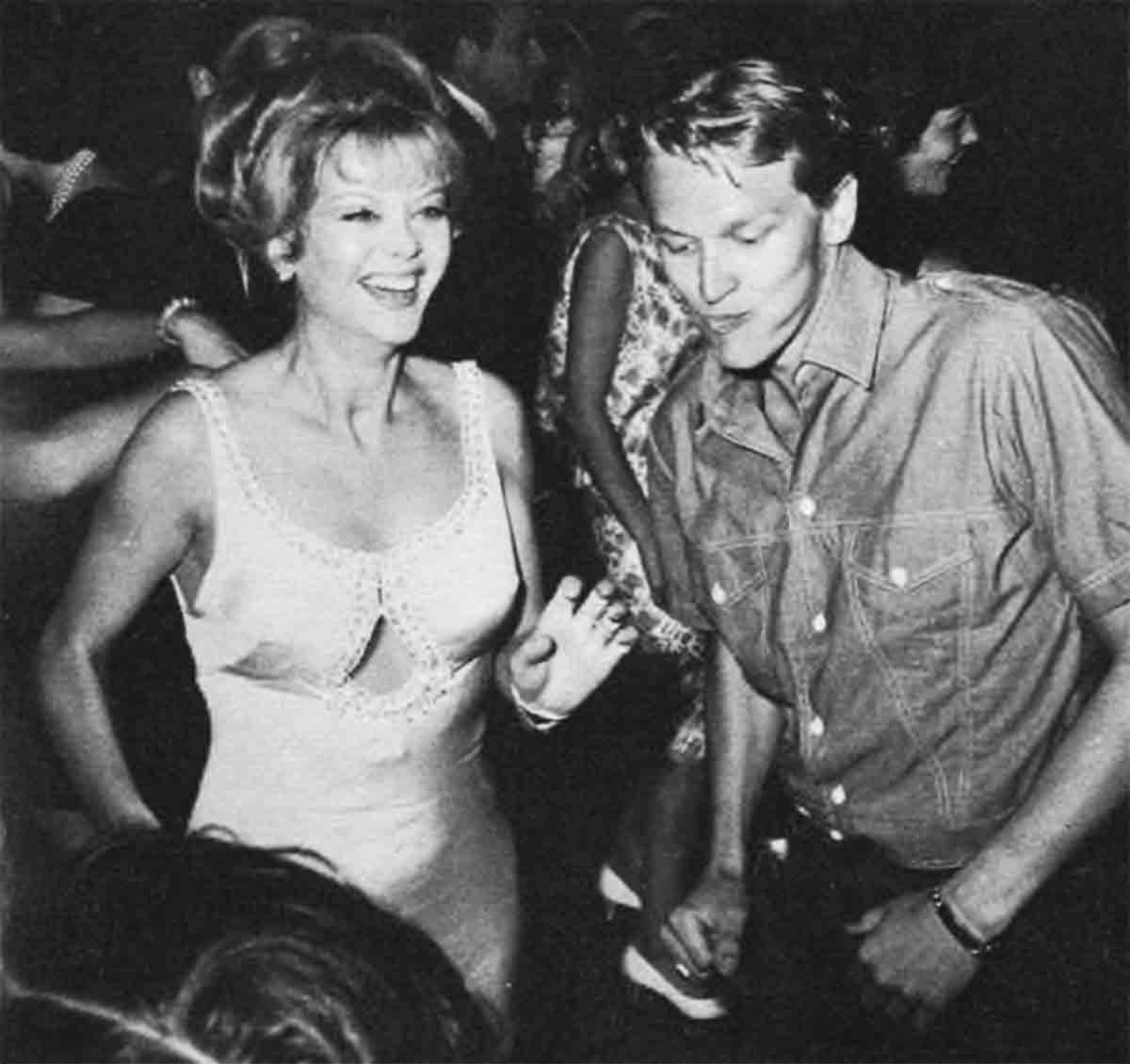

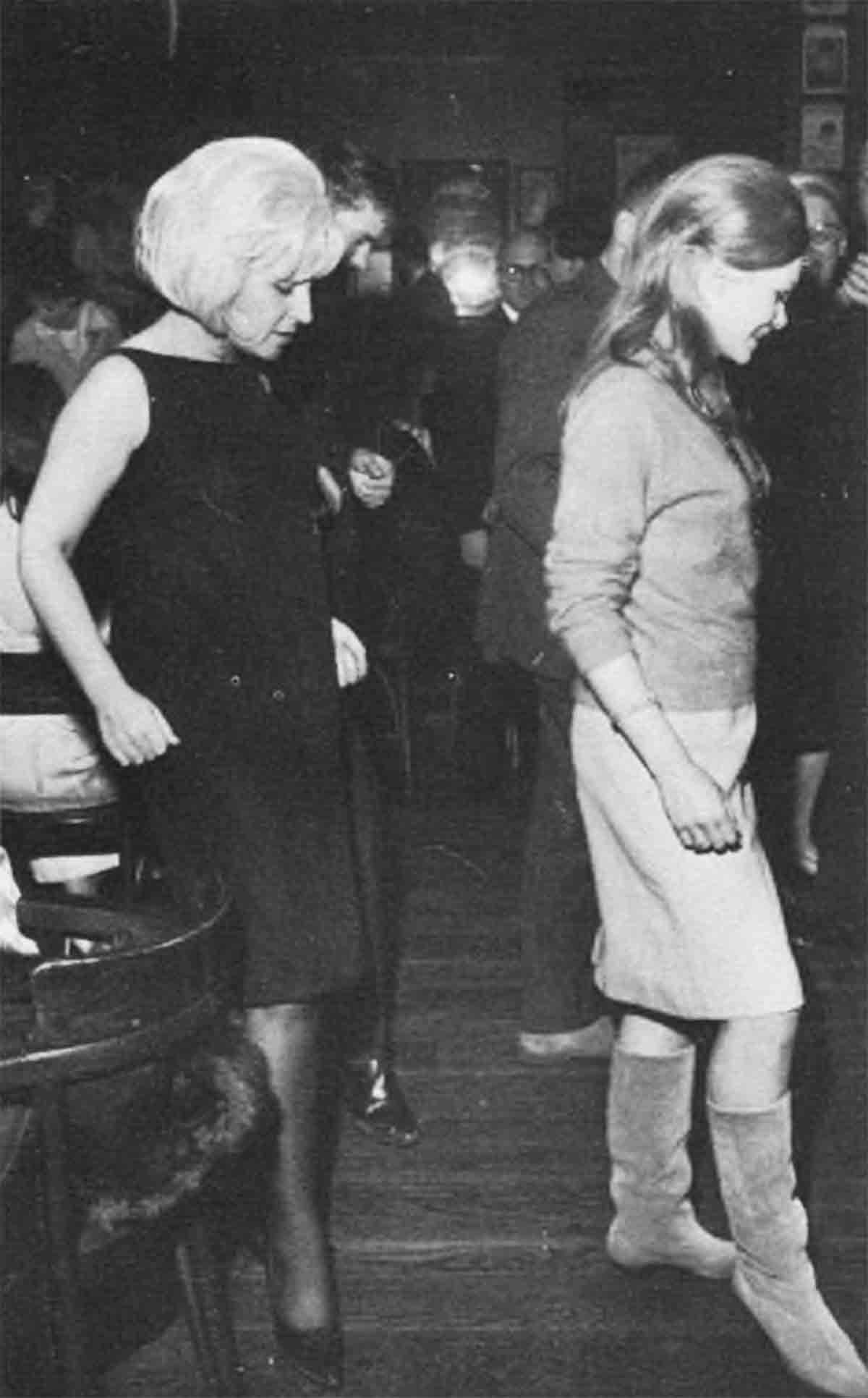

But not all the “wild ones” are on the stage. Many are out on the dance floor kicking up their heels and shaking whatever it is that you shake when you do the watusi or frug or gorilla. They are all members of the “in” crowd which views “Arthur” as a status symbol, a haven, an escape to unreality, or a means of defying convention on a scale that would cause the most far-out beatnik to shake his head in wonderment.

Unfortunately, the average citizen would have a tough time getting his foot inside the front door of “Arthur.” It is an ultra-exclusive niterie which caters to a special breed of high-society cat, and this is due to Sybil herself.

It was within a matter of months that Sybil Burton Christopher rose from comparative obscurity to three brief and separate phases in her “new” life: as the ex-wife of a stage and screen idol; as the wealthy and wandering divorcee who mixed with the great and the near-great along the U.S. nightclub circuit; as the hostess who probably could make the late Elsa Maxwell cry “Uncle” with the number and notoriety of the celebs she attracts to her young and thriving go-go palace. And, as if these transformations weren’t enough to keep tongues wagging, she proceeded to marry her baby-faced band leader before he and his “Wild Ones” scarcely had time to warm up their drums and electric guitars.

Although Sybil certainly wouldn’t be the judges’ choice for top honors in the Miss Universe contest, she is, nevertheless, enough of a looker that she can keep the boys’ eyeballs rolling, no matter where she goes. That she can charm a man is no myth. I know, because she charmed me quickly on the one occasion that I was able to crash the in-crowd curtain at the club’s front door. Sybil is soft-spoken and retains enough of the “old country” accent to make her voice interesting. But it is her graciousness which knocks a guy out. Few American gals can muster the poise and polish that Sybil does—when she wants to. When she approaches, you can’t help but notice her. Call it wiles, a form of hypnosis, or just plain animal magnetism—I’m not sure what it is—but there is something about this woman which can draw a man toward her. And there is an aura of perpetual anticipation evident in Sybil which makes you think somehow of a young girl who is about to receive her beloved’s first kiss.

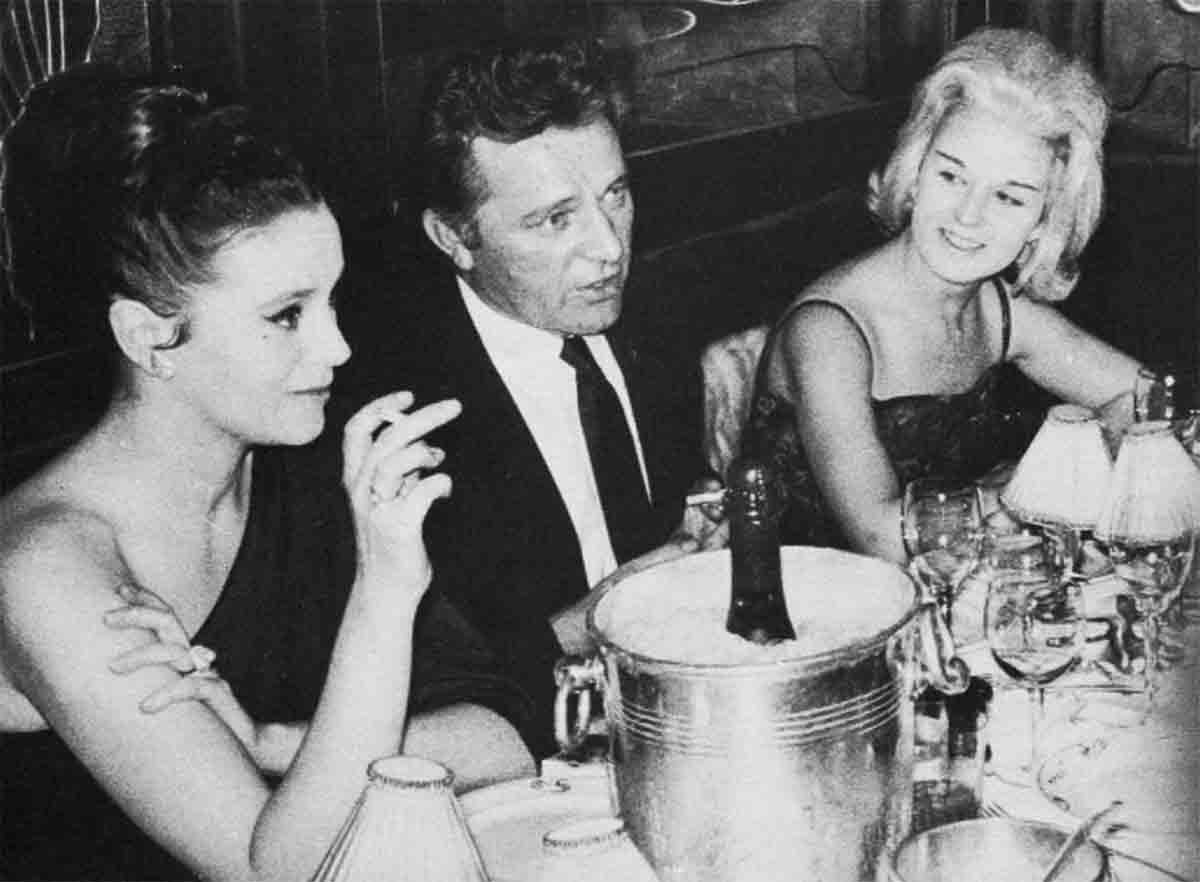

It was 2 a.m. when Sybil and I sat down recently for a chat in Arthur’s cozy Pub Room. She wore an orange pastel sheath which contrasted pleasantly with the subdued lighting and decor of the surroundings. “I’m really not a celebrity,” she said, as we sat down at a large table and ordered something to drink. “But it was so nice of you to come.” And she said it as if she really meant it. Oh, to be sure, Arthur was crawling with show biz personalities and big wheels of all kinds. Sammy Davis was there. So were Odetta, the folk singer; Dwight Hemion of ABC’s Nightlife show; Peter, Paul and Mary; James Mason; Kay Stevens; and the Judy Garland party, which included daughter Liza Minnelli and Judy’s heartthrob, Mark Herron, to name a few. But she concentrated all her attention on our interview.

Sybil is keenly interested in Arthur and in the future of her performer-husband. She also seems to have found a formula for happiness. “I love doing what I do,” Sybil said. “I wouldn’t want to trade places with anyone. One must have something to make one happy, you know. And I am very happy.” Later, as the conversation progressed, this woman—who had become an international celebrity herself despite what she believes—told me a few of the reasons for her professed happiness.

She is not reluctant to discuss the age difference between Jordan and herself. “Why should it concern me?” she asked. “Jordan and I are compatible. We enjoy doing the same things—we have a lot in common. For example, we trace our ancestry back to small countries—Jordan’s from Maced mine from Wales. People of similar ancestry know this, and they come into Arthur all the time to say hello. Besides that, my girls love him, too.” Sybil was referring, in the latter case, about her daughters, Kate, 7, and Jessica, 5, by her marriage to Richard Burton.

“The most important thing in the world,” Sybil said, “is for one to love. One shouldn’t care about being loved so much—because one does go with the other. I realized that this is what I wanted and nothing could dissuade me.” The Christophers—and the Burton children—occupy a nearby Manhattan apartment as well as a converted barn (at least through the summer months) at Quogue, Long Island. I asked Sybil how she manages to meet her daily schedules as a mother, a discotheque manager, and a new bride.

She admitted she is busier than a proverbial beaver at times. “It’s astonishing how one has to tend to things,” she said. “You know, Arthur started out as a lark. Then, before long, it became hard work. But work is good for one. Now, Arthur almost runs itself, and I come down here about three times a week; perhaps more often if there is something that needs attention. Yet, I do run my home, too.”

Sybil smiled as she spoke, almost demurely. Then she continued: “I am essentially a night person. I don’t come alive really until after 10 o’clock. Late in the evening—that’s when I’m at my best. But I love mornings, too. I go home and play with the children after they get up. Often I take a nap for three or four hours beforehand if I get home in time.” What does Sybil do in her spare time? “Oh, Jordan and I go to the theater when we can, or we drop in at other clubs about town,” she said. And she hastened to explain. that the 4 a.m. closing at Arthur six nights a week puts a crimp in social activities. The discotheque is “dark” on Monday nights only.

How did Sybil get into the discotheque business? She explains that a friend of hers, Brian Morris, had a successful discotheque operating in London. It is called the Ad Lib. Morris entertained some thoughts about opening a similar place in New York and he and Sybil were discussing plans for the venture when Morris had to back out. Sybil was working with Mike Nichols at Theater Establishment, a production company which presented Square in the Eye and The Knack in the Strollers Club building which now houses Arthur. Consequently Sybil had an early knowledge that the premises would be available. More than 70 investors put a thousand dollars each to help get the discotheque into operation, and the list of “partners” runs like a Who’s Who of show business.

While New York’s “upper crust” and show business luminaries cut loose from dusk to dawn at Arthur, Sybil Burton Christopher holds informal court at a small table in the northeastern corner of the main room. From this vantage point she can scan incoming guests from an opposite doorway as well as the bandstand where Jordan and his youthful colleagues belt out some of the loudest music this side of Ringo and his friends.

Jordan is a personable young man with a little more than average vocal talent. Frankly, as he puts it, he is occasionally overwhelmed by his sudden success. “I wasn’t much until Sybil discovered me,” he admits. The son of an Akron, Ohio, saloon-keeper, Jordan had a college drop-out record, a broken marriage, and a host of professional setbacks in New York after he migrated to the big city in quest of fame and fortune nearly six years ago. His bride-to-be auditioned him while he was strumming a guitar at the Peppermint Lounge. “I knew he was right for Arthur,” Sybil later said.

Will success spoil Jordan Christopher and his four nattily dressed musician-buddies? Only time will tell. Already they are undertaking road engagements, television commitments, a career in records, and are starting a publishing company (for their own songs), and whatever else the splash of notoriety will throw their way. “We don’t want to confine ourselves to the English image,” said Jordan when I interviewed him at Arthur, “but we probably won’t change ourselves very much in the future. We like our long hair. That’s why we wear it this way. Besides that, we all look good with it long.” The Wild Ones choose their attire together, and their onstage costume includes black mohair suits with vests; blue shirts; white silk ties and hankies; black suede Italian-style boots “which we don’t consider part of the costume, but we wear them.”

I asked Jordan and his four cronies—Tom Graves, Eddie Wright, Tommy Trick, and Chuck Alden—if they planned to continue to ride the crest of their success together into the future. They chorused that they did. What pitfalls loomed ahead of them? None, that they could think of. “We are friends and we are successful,” Jordan said. “What else do we need to keep us together?” The Wild Ones—excluding Jordan, the oldest is 22 and the youngest 18—say they will be concentrating on their own material from now on, and will take advantage of the opportunity to discard “the Top Ten bit.”

And what part does Sybil play in the development of The Wild Ones. None, according to all concerned, except perhaps to offer a little advice now and then. The same applies to Jordan. “I will not supervise Jordan’s career,” Sybil said. “We ask each other for advice but that is all. We go on hunches.” I asked Sybil if the fact that Jordan may be away from Arthur—and the home front—for prolonged periods in the future—filling movie, record, and club obligations—would pose any threat to their marriage. “Absolutely not,” replied Sybil. “It will pose no threat whatsoever.”

Besides being flipped out over Jordan, rock and roll music, and a discotheque which is named after a line in a Beatles movie, what else turns Sybil Burton Christopher on? New York does. “This city is never disappointing,” she said. “It is easy for a woman to feel all alone, say, in London. But here one has so many friends and there always is so much to do—and it’s just marvelous for youngsters.”

Of course, it is old hat that Sybil gave up a budding stage career herself when she married Richard Burton. “One could tell one would be traveling and all,” she had said, “so there was no sense going on with it.” Now, on the other hand, she claims to feel “a sense of fulfillment with Arthur—but not of achievement.” She, her age notwithstanding, believes dancing in the discotheque manner is a good means of self-expression.

When you first enter Arthur—that is, when you get by Cord, the man who does much of the initial screening at the door—you are, of necessity, wide-eyed. Not so much because of the interior decor or the jam-packed throngs of svelte and sexy girls (with their escorts). But because it is so dark inside. In fact, it is sort of a big cave done in a subdued modern decor. The furnishings are not overly plush. Instead, they are startingly simple. Black velvet benches line the walls and cushioned stools surround numerous small tables. The tables are low. Also, they are close together, for the most part—not necessarily for coziness, but in order to utilize space to the greatest possible extent. Table-hopping is frequent, and does not seem to be frowned upon, especially since in almost every case couples only are permitted to come into the club in the first place. Cameras are taboo and generally are almost useless anyway since the darkness of the discotheque room is enough to make even the most skilled cameraman shudder as he gropes for his light meter. Sybil chose the club’s decor, and black is predominant. The walls are black, with red wool jersey curtains separating the main room from an elevated section where there are more tables.

Most of the time there scarcely is room for the cherubic faced waiters to get through with their drink orders from table to table. Priced at $1.75, drinks are served in sturdy brandy snifters, A minimum of $4 is observed during the week and is hiked to $5 on the weekends. The “eats” menu ranges from egg and bacon croquettes (at $2.50) to Scotch salmon (at $6.50). There is one sandwich called a Whistler’s Mother which sells for $3. Devonshire tea is a favorite of Sybil as well as many of her guests.

Except for baby spotlights which play over the wild combo on the stage, lighting inside Arthur is restricted to candles, and small blue and green lights which wink out from the ceiling. The dance floor is a sight to behold at almost any time during any given evening. To use an understatement, it is simply wild. A hundred couples are apt to barrel out onto the floor whenever The Wild Ones take over the music-making. Models, debutantes, wealthy beatniks, uninhibited wives (and husbands who are even moreso), bald-headed and too-plump business men, the Madison avenue grey-flannel set, movie stars, stage and television personalities, young, old, tall, short, dressed in every conceivable fashion, from bottom-bursting stretch pants and sloppy-joe sweaters to evening clothes, including tails and ties. The dance floor becomes sheer bedlam, with the big beat of the band drowning out all human sound, and bodies gyrating, twisting, jumping, spinning, bending, through everything identifiable, and many dances which are not.

Arthur also is unique in that no hired au go go dancers are used to show patrons the proper way of doing the frug, watusi, monkey, swim, hitch-hiker, Freddie, or other pop steps. It also is unique in that live music is presented instead: of that only from a juke box as in the case of most other discotheque parlors. Phonograph music, including standards and other slow numbers, is offered during The Wild Ones’ intermissions.

What has happened to Sybil Burton Christopher to make her not only part and parcel of such a scene, but actually the sparkplug behind the hottest discotheque in a city that is full of them? No one can come up with a pat answer, that’s for sure. When Sybil married Jordan, Richard Burton is said to have commented: “Oh, my God, no.” But another intimate of Sybil’s, a friend, said: “I hate to put it this way, but when your wild oats sowing comes late, it’s like the measles. It’s like going through a stage that most girls go through at 18 or 19.”

Obviously, Sybil couldn’t care less. Like she says, she is happy. She looks happy and acts happy. That’s more than a lot of her night-after-night customers can say. And she keeps a sense of humor about her which refuses to be scuttled by gossip-mongers and prudes.

Even at that, however, it was but a few months later that New York gossip columnists hinted that Sybil’s surroundings might become more secluded—at least for a little while. For Sybil and Jordan, the columnists dutifully reported, quite possibly were “expecting the stork.”—137. Nearly talked himself to death.”

The ape-man’s action routines also have been limited. Tarzan goes to the rescue, swinging from tree to tree, but generally the chimp beats him there and saves the day. Often when he is in danger or trapped by villains, Cheetah rescues him. When Johnny Weismuller played the role of Tarzan there had to be a number of swimming and diving scenes. Otherwise, the action revolved around jungle-lore shots of animals fighting, a stampeding herd of elephants, a river full of hulking hippos, deer drinking from a pool while a lion stalks . . . with Tarzan watching. The formula for a Tarzan flick calls for only a pinch of dramatic action. Like plodding through the jungle, the films are slow-paced except for one or two spine-chilling episodes calculated to lift the viewer out of his chair.

Realistic comedy and humor are, for the most part, lacking in Tarzan flicks. Though many a blind spot in the script has been saved by the slapstick routines of Cheetah, there is nothing to arouse genuine guffaws except Tarzan who, more often than not, is a poor straight man for the chimp’s antics.

Confident of his character and practicing his right to approve all the scripts even though he did not write them, Burroughs had calculated audience response down to the last royalty. In a scene from the 1941 Tarzan’s Secret Treasure, the writers had the hero laughing long and loud as he watched treasure hunters discover his hidden cache. Burroughs demanded the scene be cut, stating his protagonist was moody and reserved and, “not given to such outbursts.” Completely out of character, Burroughs feared Tarzan would have appeared “Hollywoodized” to his fans.

Although many of Burroughs stories dealt with the Dark Continent, in the more recent films, Tarzan has successfully swung through the timber of Thailand, Kenya, and India. Even with realism at a premium, audiences were satisfied with the crepe paper creations and lush surroundings of hastily constructed sets. One of the exceptions was Tarzan’s Peril starring Lex Barker which, with more real than reel peril, taught Lesser that Hollywood was the safest jungle in the world.

The movie company safari seemed doomed: Everything went wrong, including Barker’s tan which the continual rain washed away day by day. Finally a special body makeup was flown in to keep the ape-man a “natural” shade. When Barker first appeared in his loincloth, the natives roared with laughter and Lesser himself had to coax the sulking star to perform.

After a series of exhausting tests, a chimp could not be found in all of Kenya to play Cheetah and she had to be written out of the script. As a result, Barker quipped, “There goes our last laugh.”

To fill the gap caused by the loss of the chimp, Lesser came up with a singular piece of jungle drama: Barker would wrestle a real—live, man-eating plant. But Barker barked backed—he refused to wrestle anything that did not know when to let go. Lesser called in special effects men and they dreamed up a papier-mache substitute to stand in (with the aid of a few wires) for the non-vegetarian vegetable of the veld.

The elements continued to plague the company, and with less than half the feature in the can, Lesser ordered a retreat to Hollywood. Upon returning, he vowed he would never make another Tarzan film in Africa again. Reviewing his hectic days as a Tarzan movie-maker, Lesser said:

“In the old days, all Tarzan had to do was fight wild animals bare-handed. But the times changed. World War II brought mechanized warfare to the jungle. Now the ape-man had to watch out for machine guns, armored trucks, booby traps, and bombs.

“Tarzan used to be considered as just a big primitive man who beat his chest and yelled, and little boys imitated him everywhere,” Lesser added. “But now he is looked up to as a symbol of wholesomeness.”

If there is no sex, no dialogue, no drama, little humor, and no real exotic background, you might reasonably ask why the films have been so successful. The answer is simple—Tarzan is a living legend. The ape-man and his fight against the white man’s invasion and corruption of the virgin jungle are the only ingredients necessary for the magic that continues to draw big box office, no matter who wears the loincloth or goes screaming through the treetops.

Now 51, Tarzan has a new producer, Sy Weintraub, and another alter ego, former stuntman and Tarzan number 13, Jock Mahoney. Braving all wrath, Weintraub has eliminated both Jane and Cheetah from his films, yet his coffers have been filled.

“The right formula,” claims Weintraub, “is that of a legend: We take Tarzan and put him in a reasonably believable situation. The trouble is that Tarzan is an extra character. But if you get a great story, it revolves around people, and to include Tarzan you have to tilt the story angle. Yet it can be done. The trick is to modernize him without losing his basic appeal.”

Burroughs agreed, claiming the basic appeal of Tarzan lay “in the latent inclination of all people to see themselves as either heroic or beautiful, or both. Deep within all of us,” he said, “is the recollection of the days when we were Tarzans ranging the primeval wilderness of the earth’s dawn.

“We wish to escape—not alone—the narrow confines of city streets for the freedom of the wilderness—but the restriction of manmade laws and the inhibitions that society places upon us,” Burroughs said. “We like to picture ourselves as roaming free, the lords of ourselves and of our world; in other words, we would each like to be Tarzan.”

There are thousands of others who have also admitted their desire to be Tarzan. And so will future generations who watch the ape-man continue his never-ending adventures through the jungle. Since the film scripts have exploited all the locations on earth, we can expect to see the Tarzan of tomorrow—sans space suit, without shoes—not very far behind the astronauts exploring the wilderness of Mars.

After all, what’s a jungle without a Tarzan there?

THE END

—BY DAVID REED

It is a quote. BEAU MAGAZINE AUGUST 1966