Poverty’s Child—Sheree North

When Photoplay asked me to write about the years I spent with a purse thinner than a slice of ham in a drugstore sandwich, I felt like saying, “Folks, you’ve come to the right person.” Because, until 20th Century-Fox signed me to a seven-year contract, being broke had been the story of my life.

I don’t have to search very far back in my memories for times when the absence of money almost overwhelmed me. Almost—but not quite. For poverty, which can be a frightful, degrading experience, does either of two things to you—it calls out all your resources and strains your ingenuity to the utmost, or it causes you to sink under a load of self-pity.

AUDIO BOOK

I well remember four years ago, when I was nineteen, in New York for the first time, and almost ready to sink. It was Christmas Day and I was propped up in bed sick with the flu, wearing two sweaters and my bathrobe to keep from shivering. I was staying at a third-rate hotel off Broadway at 54th Street. Dirty wet snow and freezing rain glazed the window. But the view wasn’t marred, since there was only a brick wall to see anyway. My little daughter, Dawn, was 3000 miles away, and her only Christmas present from me was a long, loving letter. I was $8.52 from being flat broke. The producers of the Broadway musical, “Hazel Flagg,” had decided to omit the dance I’d come from Hollywood to do. When they’d asked me not to report for rehearsal, I’d hit bottom. Now, tears of loneliness for Dawn trickled down my cheeks. Taxi horns sounded outside; inside, the quiet was broken only by a boiling coffeepot.

My roommate, Chris Carter, who’d come with me from Hollywood, opened the door, shaking the wet snow from her coat. “Well, I got the yogurt and the coffee,” she said. “And now for our Christmas dinner.” In the electric coffeepot, plugged into a light socket, were two potatoes. Chris stabbed at them with a fork. “They’re done,” she said, fishing them out. From a suitcase she got two plates and cups, then she spread a towel on the dresser for a tablecloth. “Now, I’ll make the coffee,” she went on. “Gee, I hope we don’t blow the fuses again until the coffee is finished.” From a dresser drawer Chris extracted two stale rolls, sprinkled them with water and put them on the radiator to soften. Then she opened the window to retrieve the yogurt bottle filled with Jello, which she’d made by the simple expedient of adding hot tap water to the powder and leaving it out on the window sill overnight.

The phone rang. It was a friend in the “Hazel Flagg” cast, calling to say that the producers had finally decided to leave my dance in. Jubilantly, Chris and I drew up chairs to the dresser. I surveyed the dinner, murmuring, “Well, no rich wine sauces to give us the gout.” And just as the coffee bubbled in the pot—bang—the fuse blew and our light went out.

I began to hum, “There’s no business like show business . . .” and Chris and I doubled up with laughter while angry hotel guests in the hall yelled, “Hey, what’s with the lights? They’re out again!” Almost every night at dinnertime they went out—thanks to our contraband coffeepot.

Fortunately, Chris and I had the saving grace of laughter, which helped us through those rough days. My dance—a burlesque of Salome and the Seven Veils—received wonderful notices, and from then on that wolf outside the door fled to greener pastures. My name went up in lights and my picture was put on posters. It was exciting, but after the show I still had to soak my aching feet. The papers called me an overnight success. Take my word for it, thirteen years—hungry, frightened years of dancing—make one long, lonesome, heartbreaking night.

But before that, Chris—a luscious, offbeat, red-headed character—and I had learned to make do. We had utilized all our courage and mainly our battered senses of humor to keep our heads up during that gloomy period in New York. I hadn’t wanted to leave Hollywood when Robert Alton, the choreographer, had asked me to give up the safety of my $42.50 hoofing job at the Macayo, a little night spot, and try my luck in New York. I fought against leaving my little girl again, and in fact, I’d about decided I was a failure at the work I’d loved and been studying since I was six. I was ready to turn in my tap shoes for a typewriter. Toward that end, I’d been saving a little each week to take a secretarial course. I even had the promise of a job at Hughes Aircraft and planned to change my name to something less flamboyant than Sheree North.

But Robert Alton kept telling me what a great future I’d have on Broadway if I succeeded, so finally I agreed to go, if Chris could go along as my understudy. By the time I’d left two weeks board money with the mother of a chorus friend to care for Dawn, bought a cheap suitcase, golashes, a thin, full-length gray coat for $12 at Lerner’s (which was laughable against the icy winter in New York), I found I had just enough for train fare and expenses to last a week until payday in New York. In the matter of a winter coat, Chris was worse off than I. She’d found a remodeled old mouton coat at a rummage sale and considered herself rather chic in it. But the first time she wore it in the rain, it smelled like a Chicago meat-packing house, and poor Chris had to shell out $15 from her dwindling supply for another coat.

And dwindle the money did. We thought we were a couple of hep characters when it came to show business, and we expected to go on rehearsal salary right away. When we discovered it would be five weeks before we got paid—and then only $30 a week—the news rocked us like a small-sized atom bomb. In addition to that, the job meant so much to us, we couldn’t risk being late for rehearsal. So the first morning we took a cab. It seemed like a long ride, and the fare was $1.50. Tired after we were through, we didn’t feel like a long walk, so we took a cab back to the hotel. Fare: $2. It was only by accident, that days later, we learned we were only two blocks from City Center and that the cabbies had played us for suckers, with trips through Central Park and back.

We didn’t want to tell anyone how broke we were, so we made a game out of merely existing. Since we only had summer dresses, we wore Levis under our coats to keep warm. In California, Levis are fine, but not in New York. So we’d roll them up, put on high heels and go to a cheap restaurant for breakfast. Naturally, we couldn’t take our coats off. We’d case the tables to see which one had the biggest pile of rolls in a basket, then order coffee and a ten-cent bowl of mush. And while Chris made up to the waiter like mad, I’d stuff my purse and blouse with the rolls. They’d dry out in the hotel room, so when we’d get hungry we’d pour water on them, then put them on the radiator.

To this day, I believe we kept from starving only because Chris had a lot of boyfriends back in Hollywood. When they wrote, saying they’d like to send her a gift, she’d tell them what she really needed was an electric coffeepot or a hot plate or a broiler. All this gear we’d keep in a suitcase, away from the watchful eye of the hotel maid. When we went to Philadelphia for the tryouts, we had to lug all this stuff with us. And by that time Chris had even promoted a set of Revere ware. For radiator cooking, yet!

Following a year on Broadway, I got a spot in the film, “Living it Up,” then, on TV, an appearance on the Bing Crosby show, and finally a film contract. After that, I went around with an expression of permanent surprise at money coming in each and every week. I wasn’t cast in a film for a whole year, and that made my solvency seem even more remarkable. It was the first time I’d ever had a vacation with pay.

My immediate objective was to learn all about insurance—from education funds for Dawn to accident policies and annunities—and to invest my spare cash in them. That was the direct result of long years of insecurity—of wondering where money for baby food for Dawn and bean money for myself was coming from. One sad result of my new financial status was that I was constantly hungry, and I began to put on weight. I’d come back from a three-hour dancing lesson, open the well-stocked refrigerator, and eat everything in sight, Partly, it was nervous jitters at the thought of acting in pictures with experts, and partly it was trying to make up for all those hungry years.

Like so many others, I was a Depression baby, born in a fourth-floor apartment in the shabbiest end of Hollywood. Added to that, my father walked out before I was born. I’ve never seen him or even a picture of him. We moved from apartment to apartment when we couldn’t pay the rent. There was Mother, Grandmother Shoard (with a Scottish accent as thick as the oatmeal porridge she fed us), Janet, my half-sister, Don, my half-brother, and a changing cast of hard-up relatives. Sometimes we were on relief, sometimes, in addition to the oatmeal, we managed a lamb stew. I recall that, when childhood hurts brought tears, Grandma never said, “Here’s a nickel to buy some candy.” Instead, but not frequently, she’d say, “Come in the kitchen and I’ll boil you a nice eeg.” That was real luxury.

Mother worked alternately as a practical nurse, floorwaxer in office buildings, and as a pearl-bead stringer and jewelry appraiser when she could find that type of work. In her harassed struggle to support us (and this is the saddest thing about poverty), she didn’t have time to mother me. And my older brother and sister were out fighting their own battles. I earned my first dollar when I was five, helping mother string pearls. I figured I’d been paid for having fun. I soon found out the second dollar was work. But I didn’t mind helping to keep a dancing studio clean so I could have lessons. Nor did I mind long walks or hitchhiking to get to the studio for my lessons. When I was eleven, an uncle taught me to drive his truck, and soon I was earning fifty cents helping some boys park cars at the Christian Science Church on Sundays before I went in for the services. Later, I heIped park cars at Ciro’s and the old Trocadero’s for a dollar and a hamburger. Without money, you grow up fast.

By the time I was thirteen, I considered myself a professional dancer, ready to get a job, dancing in the chorus at the Greek Theatre during the summer season. The child labor law enforcers wouldn’t have agreed with me, so I lied about my age, swiped my sister’s high-heeled pumps, stuffed my bodice with cotton, and bought a fake hair fall. When you grow up fast, you learn to use your wits. As soon as the summer was over and I was out of a dancing job, I lined up at the unemployment office, getting enough money to continue going to school. At fifteen, I eloped to Las Vegas, hoping to give up the struggle to support myself. But a year and a half later, I had a daughter to support and no husband. Marriage is obviously not for children.

I went back to dancing at the less important night clubs. I took the baby with me because I couldn’t afford a baby-sitter Someone has said, “The poor would never be able to live at all if it wasn’t for the poor.” Knowing what it is to be broke tends to humanize you, to make- you responsive to the needs of others. The girls backstage were wonderful to Dawn—and me. With just enough money to see them through the week, not knowing if they’d be working the next week or not, those girls had developed a compassion for the struggles and hurts of others. I, myself, didn’t escape this desire to help. If we had a dollar we’d give a needy friend fifty cents of it. When Chris was out of a job, I’d be breadwinner for both of us, and she did the same for me.

I hope I never lose this desire to help others—whether it’s with money for a needed operation or illness; help in finding a job, watching a performance and bringing it to the attention of the right people; solving some problem; or just a sympathetic ear when marriage problems are overwhelming. Sometimes, just a good dinner or an understanding letter or phone call can work wonders.

For these are the things that poverty teaches you—the things a child brought up in self-centered luxury doesn’t learn unless there are wise parents. And that’s why, though I hope Dawn never has to make her way unaided, I still don’t want to spoil her. Just the other day I asked her if I might borrow her little record player so the group who come to my dressing room to rest during lunch hour could have some soothing music. I could have bought another record player; however, I wanted Dawn to understand what sharing meant. That’s also why Dawn doesn’t get an allowance, but she does get paid for keeping the den in order. I don’t want her to have to learn the value of money by parking cars at Ciro’s during her teens, but I do want her to learn the value of money.

Although I thought I’d learned the value of money, I found that I was frittering away a good part of my salary on non- essentials. The answer was getting a business manager—a hard-hearted man who has put me on a strict budget. If I ask for money to buy new draperies he says, “Why don’t you make them yourself? My wife does. Why put a lot of money into draperies for a rented house, when you plan to buy or build your own home?” He was right—after I thought it over a while—and I did make them. They’ll never get me admitted to the interior decorators’ union, but they’re adequate. And, if ever I get a sudden mad yen for an electric blender or some such, I find it easier to save out of the household money and buy it than to go through a session with our business manager.

I’m a realist who only believes in cash in hand. Since my salary checks go directly to my business manager, they’ve lost their meaning to me. Consequently, when an agent offers me a hi-fi set or an assortment of French perfume in payment for a TV appearance. I’m inclined tc grab it. If he offers a check, I’m not so interested—though I could buy a number of hi-fi s and enough perfume to bathe in with the check.

Suddenly finding yourself with more income than you’ve ever dreamt of isn’t an easy thing to assimilate. The history of Hollywood is filled with tragic stories of stars who earned tremendous sums and, once past their acting days, found themselves in sorry financial state. And there are top film personalities today, drawing huge salaries, who are dreadfully in debt both to Uncle Sam and others. They can’t seem to remember that, after taxes, they are not going to receive the figure on their salary checks, but anywhere from fifty to ninety percent less than that sum. You can’t buy a closet of Dior gowns, a fleet of Cadillacs, an assortment of houses on ten percent of your earnings—unless you’re Rockefeller.

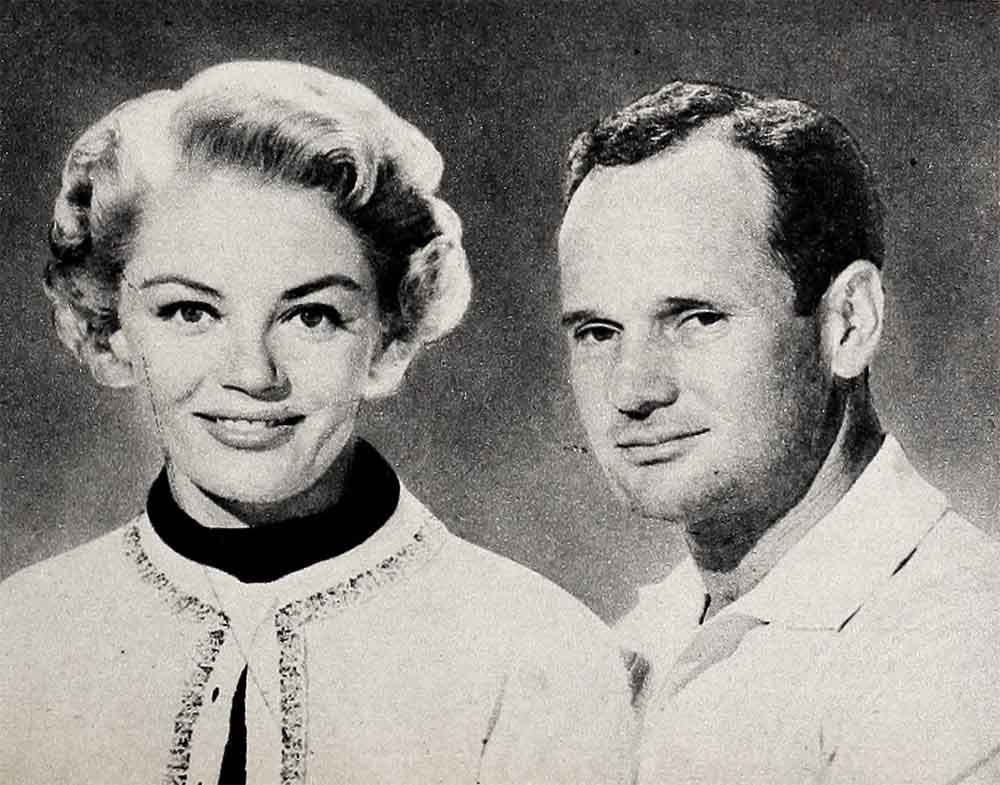

My husband, Bud Freeman, and I are certain that we’ll never go into debt; we’re not the type who tries to impress the Joneses. Personally, security means too much to me, because I can still remember how my feet hurt when I bought my first high-heel pumps. Having only three dollars to spend, I went to a shoe outlet store on Hollywood Boulevard. All I could find in my size were a dreadfully narrow pair—4 A’s. I bought them anyhow, and danced away the night on my first date at the Cocoanut Grove. Ah, youth.

Years of being broke make you not only realistic but sometimes too cautious, afraid to leave the nest of a small security and try your wings. So opportunities pass and memories become bitter. And injustices can rankle deep and corrode when money is involved. I remember when I was dancing in a night club for $42.50. The management was supposed to furnish new costumes, but didn’t. The ones we had were in tatters and we’d spend hours keeping them in repair. There’s a union that prohibits that, and once I was caught mending my costume and fined $50. It seemed that such work should have been done by a wardrobe mistress, but we didn’t have one. Did the management repay me? That’s a laugh! Two weeks later, they were going to fine us $50 each again for wearing our own shoes. The ones the management bought us didn’t fit and were falling apart. I solved that crisis by quitting.

It’s no wonder, then, that money had real meaning for me. With my new contract, the thing I wanted most of all was a home for my little girl. She and I had never had one. But again caution overcame this natural desire and I rented a rundown cottage thirty miles out in the Valley where rents were cheap. I drove a beat-up 1949 car with holes in the roof, I lugged the laundry to the laundromat, I watched the ads for Thursday grocery specials and shopped around, I saved plastic bags and string and continued to use kitchen matches (my own patented cigarette lighters). It was hard for me to spend money on myself. My clothes came from Ohrbach’s, where one serves oneself and saves; I bought a little straw skimmer at the drugstore for sixty-nine cents.

And so I was much amused when I read in the columns: “Sheree North in an expensive cocktail suit and chic hat at Ciro’s last night.” That expensive cocktail suit was $39.50, and the hat cost $5.95. I’d learned to know values and style from constantly reading fashion magazines, and from my model girlfriends, who buy basic simplicity and good fabrics, avoiding loud colors, fripperies and high style.

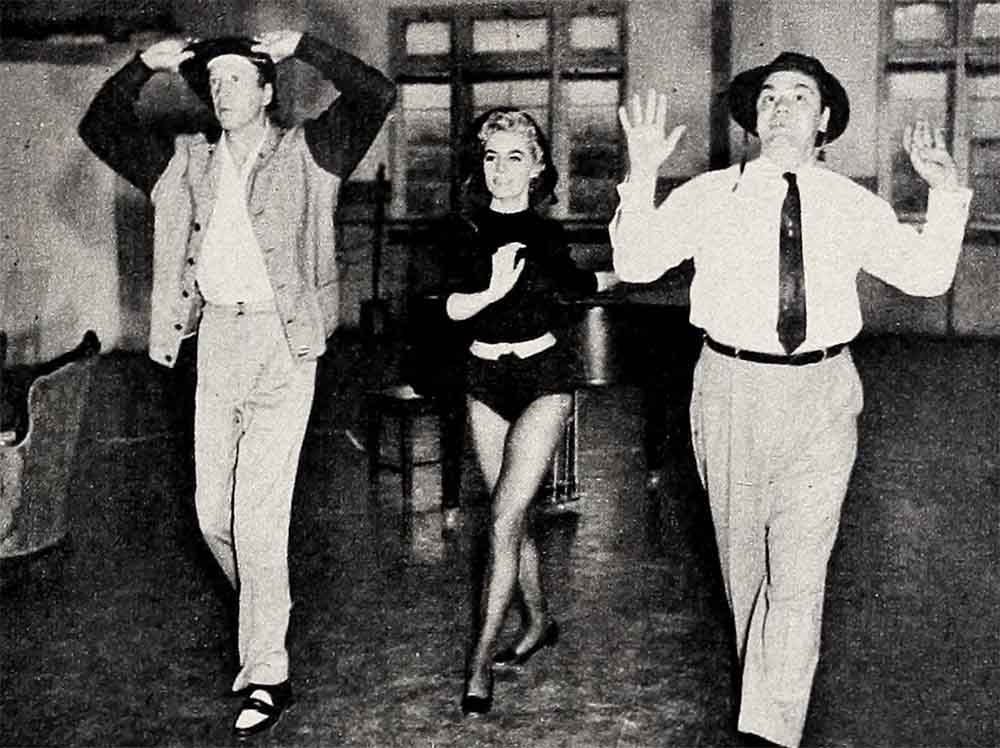

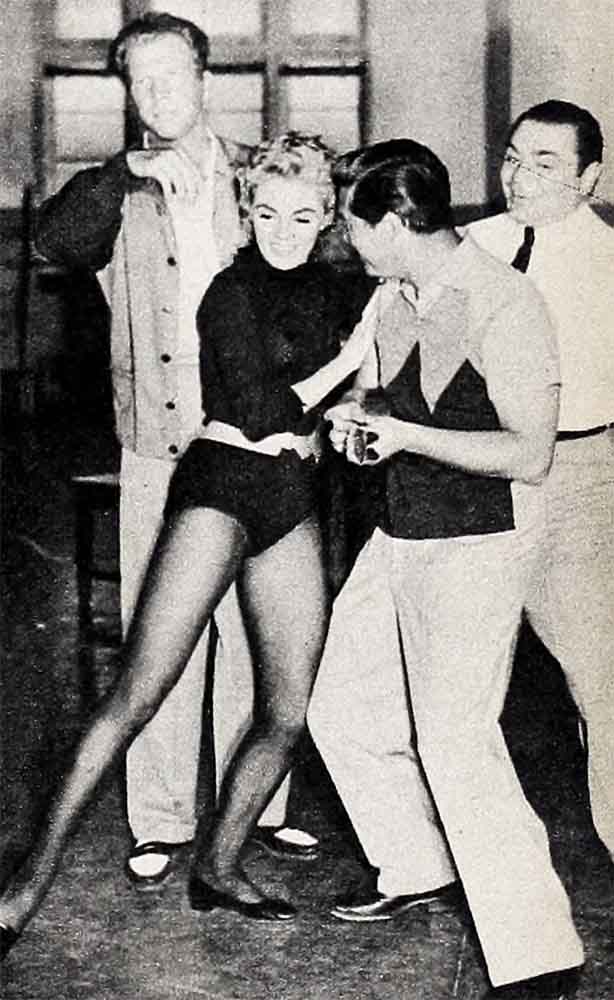

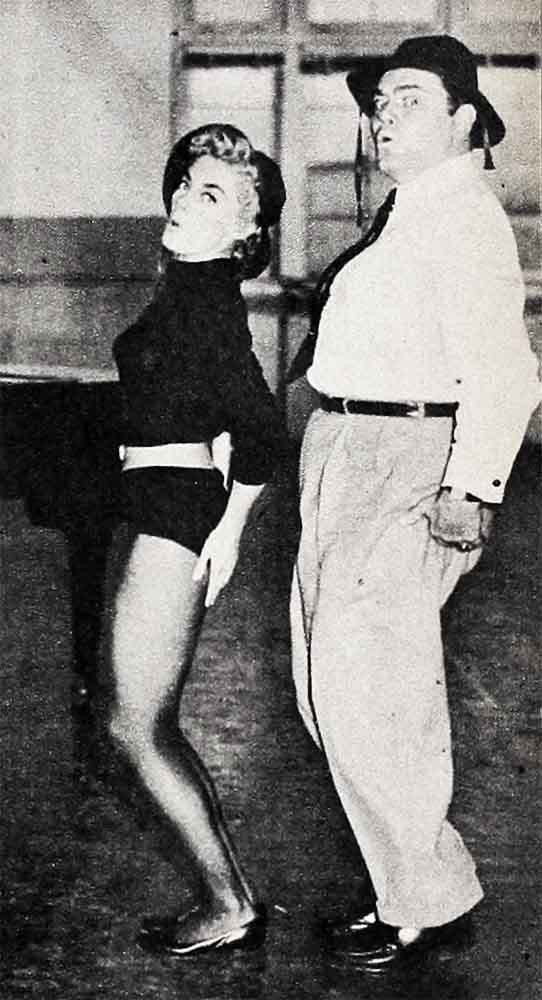

Although I love and can afford clothes, I find that today I don’t need an extensive wardrobe. At the studio I wear rehearsal leotards and tennis shoes. At home I wear toreador pants and blouses. And if I must attend premieres or make out-of- town appearances, the studio furnishes the clothing—too fancy, I’ll admit, for my own personal taste.

The odd thing, I’ve found, is that since I don’t have to count my pennies, I’ve become more subdued in my appearance. I don’t have to bleach my hair platinum, cover my face with make-up, or wear revealing dresses in order to get a job in a night club. I can be myself. And that means letting my hair go back to its natural brown and grow out—sans permanent—except when I’m in a picture. Then, it seems, gentlemen still prefer frizzy blonds. I like to pull my hair severely back from my face in a chignon and wear smart little hats. I’ve always loved severely tailored, simple suits, and now I wear them. I dislike costume jewelry, bright colors and too-fancy shoes. Columnists are amazed; they call me the new Sheree. I’ve found a wonderful Chinese girl who makes me a few basic dresses, well-fitting, and that’s all I need for the infrequent occasions when Bud and I go out in the evening. He doesn’t care for night clubs. As for me, they give me the shakes; I’ve had it from the other end of the room.

Frankly, I suppose that I don’t feel like a film star. And, knowing me, I never will. I’m giving a lot of thought to my career and I’d like to have some integrity about my work. But I don’t fool myself. I know that girls like me are hired mainly for their legs and faces—visual aids to entertainment. What’s more, we’re darn well paid. I know that musicals are what I can do best. And I like that nice paycheck coming in every week. Whether you emote like mad or just do something nice and fluffy, the color of the money is just as green. And it sure beats working in the chorus line. I’m realistic enough to know that a dancer doesn’t last forever. That’s why I want money in the bank, and a home of our own someday when we’ve saved enough for it.

Maybe financial security has meant toe much to me; I don’t know. Maybe it would be better to have a more spiritual attitude. Philosophers have long held that the “best things in life are free”—which by the way, is the title of my new picture—and millions of gags have been written about money not being everything. I admit all that is true. The only thing is that, to appreciate the best things, you’ve got to have a little peace of mind, and you can’t have it when the rent is overdue and baby needs new shoes and even the butterflies in your stomach are starving.

In my youth, I was exposed to the religious beliefs—that one is surrounded by abundance; that worry over material substance is incorrect thinking; that everything one needs for the good life is at hand. I must say this hasn’t worked for me. But I’ve seen it work beautifully for those who can and do believe, waiting quietly for God’s good to manifest itself in their lives. But I couldn’t do that. I had to scramble around, taking every honest job I could get—from waitress to model to dancer. Jobs sometimes as far away as Texas or Mexico or Las Vegas, which meant leaving my daughter, against all my deepest instincts.

And, although I’ve read many books on positive thinking, I can’t completely subscribe to that method of meeting life’s problems. For some people it works wonderfully. They take the positive approach, regard only the good, the plus side of every situation, and reap the benefits of the magic of believing. But that’s not for me. I want to protect myself by considering the negative side, too, anticipating what I’ll do if the bottom drops out of things.

I don’t want that to happen to my career. That’s why I take daily dramatic, singing and dancing lessons. Symphony musicians on vacation carry their instruments all over, because if they cease practicing for even a day they get out of condition. It’s the same way with a dancer. My teacher is rather drastic; she just doesn’t believe your muscles won’t stretch to a certain point and then way beyond it. It’s torture—but for a good cause. When I’m working, I carefully take my professional make-up off before I go home because I want Dawn and Bud to see me looking fairly normal. Then, when I get home, I have a nice long talk with Dawn about what happened at school and at the playground, next a session in my bathtub with my Whirlpool which takes out all the kinks in my body, then I’m ready for a hearty dinner (I’m on a perpetual-motion diet). If Bud asks me how I feel, I say, “Oh, just medium hysterical.”

But the real truth is that I feel wonderful . . . because I’ve had it bad—but today I’ve got it real good.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1956

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments