Natalie Wood reviews “The James Dean Story”

I love movies. If I didn’t, I’d be in some other business. Just the same, I dreaded going to the screening of “The James Dean Story.” I was invited to the first Hollywood showing, put on by the Screen Directors Guild. As you must know, this picture had a personal meaning for me. And it must have had the same hypnotic appeal for a lot of other people in the industry, because the theater was packed. I noticed several of Jimmy Dean’s friends there—people like Dennis Hopper, Marlon Brando.

I’m sure they felt just as I did: Can we last through the picture? Will we still be here when the title “The End” comes on and the projectionists shut off the machine? I didn’t think I would be there.

But I was. The picture held me from start to finish. I’ll tell you why we were all worried. We weren’t afraid of being overcome by emotion. We were afraid that the picture would distort and change the Jimmy that we knew. Sure, he wore a‘leather jacket and motorcycle boots; sure, he raced his cars. But the violence that accompanies too many of the kids who follow him was not part of his makeup. And we were afraid that this stranger Jimmy Dean would be the boy in the picture.

We all knew that this film was designed for one purpose, like most movies: to make money. But this moneymaking venture was based on the death of a friend of ours. I thought that Jimmy Dean’s death on September 30, 1955, would be just the basis for somebody’s financial gain. So I was ready to get up and run out of the theater. I didn’t, because I found myself looking at a picture beautifully done, in the best of taste.

The makers of “The James Dean Story” were as honest as they could be in making this film. And it could have so easily been what I feared. We’ve heard too much of the legend about Jimmy Dean. This legend would have been the practical reason for making a profitable picture about Jimmy. Instead, the picture destroys that reason. It separates the legend from the real Jimmy Dean. And, at the same time, it shows us both.

More important, it establishes—and it does this definitely—that he is dead. The pictorial reenactment and later evidence shown should stop, once and for all, the ghoulish tales that try to contradict the death certificate. These weird stories have only disgusted and saddened people who really loved him, because we know he would have accepted the fact of death just as he accepted and welcomed life. It’s something that happens to all of us.

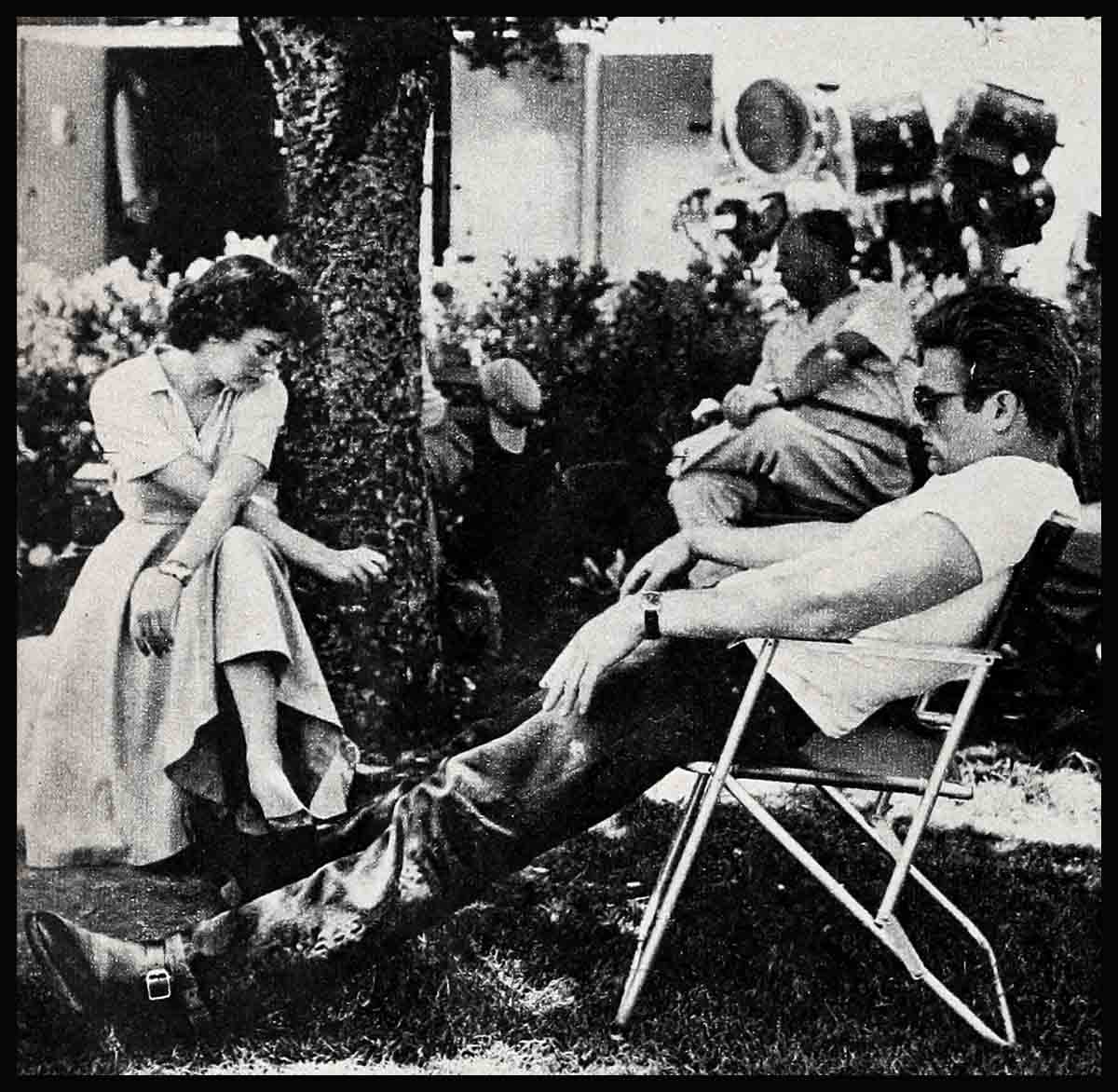

Watching this full-length feature, running eighty minutes, I was fascinated by the amazing quality of the black and white photography. The biography-documentary is told in a most unusual fashion, combining film clips of Jimmy, his family, his friends, his acquaintances who might have become friends if there had been more time. Clips from his three movies are included, so moviegoers can compare the Jimmy they knew with the Jimmy his close friends knew.

Some of the real-life footage is truly great. And some of it looks pretty corny and amateurish. But that only makes it seem more real, because it’s like the home movies you might take in your own backyard—of people you know as well as we knew Jimmy.

The movie often uses still pictures of Jimmy and his friends. And the “Camera Eye” technique brings all these to life. On the sound track, you hear Jimmy’s voice or the voices of people who knew him or the voice of Martin Gabel, a fine actor who does the narrating. The whole story is tied together so well that it seems like any of the wonderful feature-film biographies made about famous personalities, in or out of show business.

“No matter how long I live,” you hear the voice saying at the beginning, “it won’t be long enough.” Then come the terrible noises of the crash on the road to Salinas. And the narrator says: “James Dean died today. He lived with a great hunger.”

Quickly, the scene shifts to a year later. “Giant,” Jimmy’s last movie, is being premiered at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood. And the crowds present aren’t all there for the picture’s living stars. Why has Jimmy Dean become such a great star so quickly? Why is he still loved, followed with such unparalleled enthusiasm?

The picture tells us why. It takes us back to Fairmount, Indiana, where Jimmy went to live on the farm of his aunt and uncle, after his mother’s death. We meet the aunt, uncle, grandparents, high-school teacher, basketball coach, motorcycle-shop owner—all interviewed before the watching and listening cameras and microphones. Their recollections of Jimmy seem completely honest. No professional actors or actresses could possibly copy the way they talk. I know. I’m an actress, and I know only two kinds of people could talk like this: the greatest actors in the world; or real people, just saying simply what they really think.

Then the camera shifts to the Sigma Nu house on the UCLA campus, where a couple of Jimmy’s former fraternity brothers tell us about the experiences they shared with him. After this, New York City: excitement, hunger, frustrations that accompanied’ his struggle to get ahead in the theater world.

Now we come to the Hollywood part of Jimmy’s life, and I can tell you that the movie’s producers have made the right choices again. We hear from Patsy D’Amore and Billy Karen of the Villa Capri restaurant, who affectionately remember the many evenings he spent at their place. And, as an actress, I can assure you that the fanciest Oscar-style acting couldn’t measure up to sincere talk like this. The same is true of Lilli Kardell, a Hollywood girlfriend of Jimmy’s, and pals Glenn Kramer and Lew Bracker.

The ending really stopped me. I heard a tape recording of Jimmy’s voice, talking to his family and trying honestly to discover what made him tick. I kept thinking that the ticking was going to end so soon afterwards—too soon.

All of us—Jimmy’s friends—want to thank the producers of the picture for showing him this way, as he really was. We were so afraid of the unhealthy legend that made a hero or a young god out of him. He was just one of us, an eager young person who desperately wanted to accomplish something. Was he trying when he destroyed himself? We don’t know.

Ironically, this movie shows how much he could have accomplished in his work if he had had more time. Jimmy Dean could have handled any type of role, beyond the single-themed parts he played in “East of Eden,” “Rebel Without a Cause” and “Giant.” One thing is certain: “The James Dean Story” will encourage more re-issues of those films. And that’s good news. Here, of course, I’m prejudiced. Yes, I was a friend of Jimmy Dean’s. And I love fine movies, no matter who’s in them.

Maybe I’m prejudiced in another way, because of my age. “The James Dean Story” is the story of a unique young man—but he was like the rest of us in a good many ways. Looking at him so closely, we may understand ourselves better.

Stewart Stern, who wrote the screenplays for “Rebel Without a Cause” and “The James Dean Story,” says aptly of Jimmy: “He believed that the cry of the world is for tenderness between human beings—all human beings—and he felt that to be tender requires more courage of a man than to be violent. Men are brave enough for war, but not yet brave enough for love. That’s what Jimmy thought.”

I feel this very strongly, because it’s what we were all trying to say in “Rebel.” In that picture, Jimmy wasn’t misunderstanding—people were misunderstanding him. He was not the rebel; he was hungering for sympathy and guidance.

“The James Dean Story” will please Jimmy Dean fans, of course. As for people who can’t understand why there still are Dean fans—now they’ll know.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957