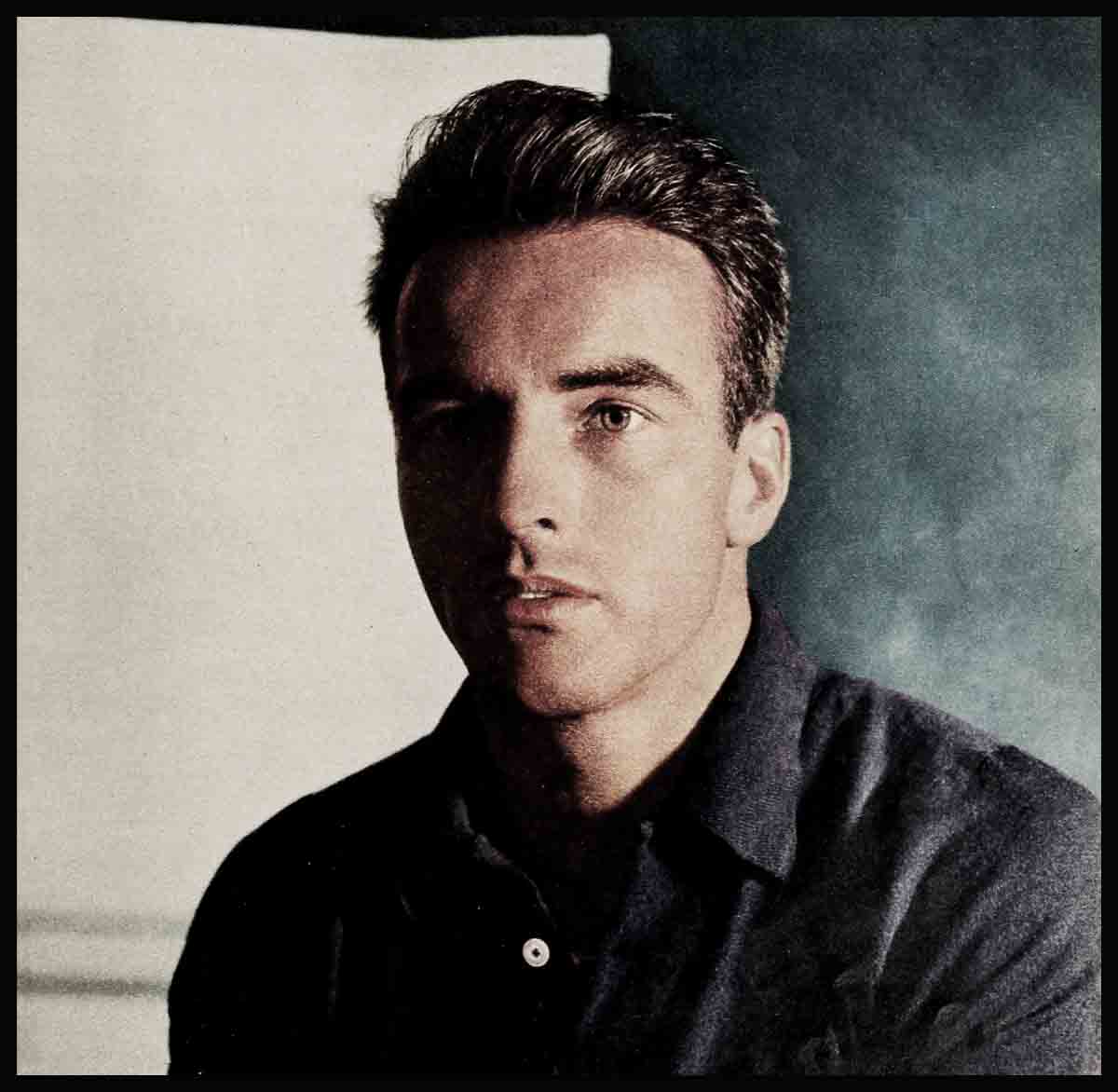

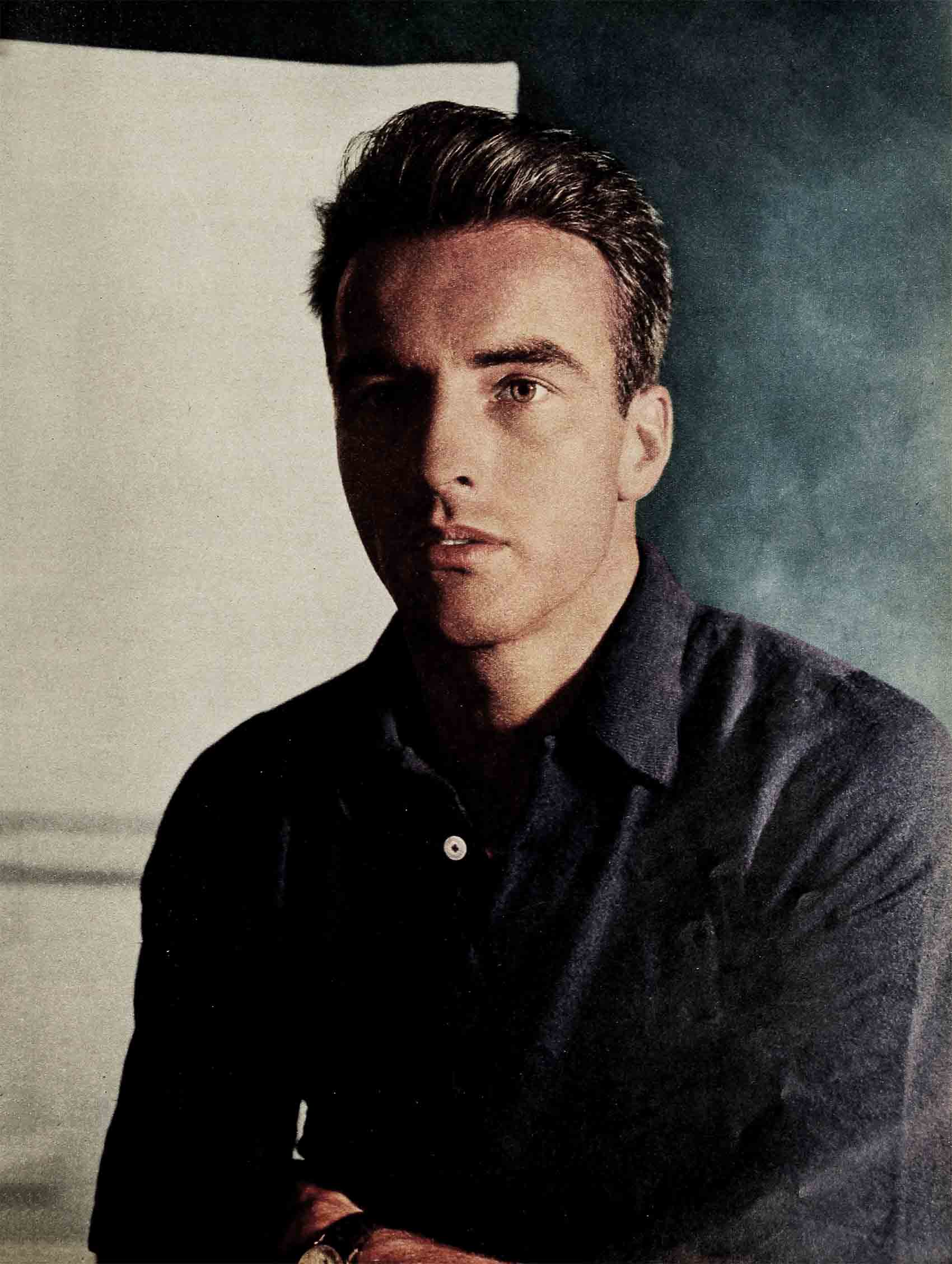

What Makes Montgomery Clift Run?

It’s always shocking to discover that a good friend Le has it in him to be a heel. It can be just as surprising to learn that a person you’ve written off as impossible is really a nice guy, after all.

Well, Montgomery Clift is really a nice guy, after all. The reportedly snobbish, standoffish, elusive, boorish, reserved Clift has given the infuriating impression that he-just can’t be bothered with people and that he has stayed single all this time for the want of a good enough girl.

The only trouble is, you’ve got to get to know Monty to find the niceness under his hard-shell—and it’s very hard to get to know him because once he gets the idea that you want to, he scuttles away like a crusty turtle. Or, more exactly, a frightened one. For Monty has a peculiar defense mechanism: he’s so afraid of not being “true” to his own picture of himself, that he’ll readily risk offending people rather than let them think, perish the thought, that he’s a glad-eyed hail-fellow in pursuit of them. So he runs away.

A typical incident occurred in New York last summer. Late one night a young photographer mounted the rickety steps backstage at the Phoenix Theatre on lower Second Avenue. From the alley below rose the hubbub of the departing audience that had just applauded the final curtain of Anton Chekhov’s moody masterpiece, “The SeaOn the dark landing the youth tapped on a dressingroom door, and blinked in the bright light as it opened to reveal the grease-painted face of Kevin McCarthy, one of Clift’s closest friends.

“I—I wanted to see Mr. Montgomery Clift,” the youth said a little timidly.

“Then come on in and see him,” said McCarthy, and pointed to the dressing table where his old friend and roommate, bare to the waist, was at work with towel and cold cream. Clift half turned around, said “Hi,” and gestured with one hand to show he couldn’t shake hands yet.

The photographer introduced himself. “I know everybody has been after you,” he said, “but my editor and I thought if I showed you some of my work, maybe we could make an appointment to take pictures of you—you know, the kind you’d like yourself.”

“Sure, I’d like to see your stuff,” said Clift, and a few minutes later he and Mcg natural-lighted portraits. While Clift sized up the work, the photographer sized up Monty Clift: the tousled dark hair, the hazel eyes looking a bit tired this night, the ruddy skin, the naked chest far from musclebound but looking healthy, hairy and suntanned.

“I like them; I really do,” Clift was saying. “I think you would take the kind of pictures I like—natural, no posed-looking stuff, me and all my pores. But here’s my problem: I’ve had to turn everybody down till the run of this play is over, because I’m putting everything I’ve got into it.

And while you probably wouldn’t distract me, if I said yes to you I’d have to say yes to them all and I’d be run ragged and I just can’t have that; I gotta concentrate on this job till it’s over.” The eyes and the frank voice seemed to implore the young man to believe this.

“Well, all I’d need would be an hour or so some morning,” the photographer persisted, “and it’d be a real break for me—” But Monty Clift shook his head. “Let’s get in touch the day we close here, or the day after, and I’ll see what I can do. Okay?”

After a few minutes the young man bade a disconsolate goodnight to Clift and the sympathetic McCarthy and picked his way down the stairs. Monty Clift heard from him the day The Seagull closed after a successful run. But the photographer didn’t hear from Monty Clift because the actor fled almost at once to rest (and to grow a beard!) in Ogunquit, Maine, from the labor of love which had netted him the Equity minimum for playing frustrated sweetheart to Mira Rostova and frustrated son to Judith Evelyn.

The young camera artist still feels snubbed and baffled. But he has the consolation of being in good company, for with rare lapses Clift has been running away from the press for years. Except for the George Evans agency, which built him up as a natural, T-shirted, male Garbo, he has been frustrating to press agents, too. He vanishes just as rapidly after a million-dollar movie, when he’s needed for publicity. Not that he’s truly uncooperative or boorish (as his loyal friends have grown a little weary of explaining), but that he’s less afraid of seeming that way than of seeming to be on the make. He remains grimly determined to sell himself on his work alone.

At thirty-four (October 17) this fear of seeming pushy would seem a little unreasonable, if not actually groundless. But it is not Monty Clift’s only fear. Apart from all his positive attributes he retains an abiding fear not of success, but of what success might do to him—make him lose touch with the “real” world. And it is fear of failure in marriage that keeps him running away from serious romance.

There have been, and still are, women in Montgomery Clift’s life. His friends say that he has been in love, and not just once. But he has seen love enter nearby lives only to go out the window leaving bitterness behind. He hates the thought of having this happen to him or to one he loved.

“I know it sounds trite,” says his brother, William Brooks Clift, Jr., director on the NBC-TV Home show, “but I think Monty’s still waiting for the right girl to come along. Sure, he could have been married long ago, have had kids by now, have had all the fun of being married—but who’s to say? Maybe he’s been right in waiting. Right now, though, no matter what you hear, I’m pretty sure there’s no ‘romantic interest’ in his life.”

The lack of one has not always stopped writers from inventing one, mythical Mary, a wealthy Eastern girl who was on the point of marrying him only to marry, for no apparent reason, someone else.

During and after the making of A Place In The Sun Monty had many dates with Elizabeth Taylor. It wasn’t for the sweet uses of publicity alone; they enjoyed each other’s company, but they never considered that they were cut out to marry each other. He used to be seen often in the company of Judy Balaban of the theatreOwning clan. Off and on for years now he has dated Libby Holman, the torrid torch singer widowed by Smith Reynolds. Many commentators have jumped to the conclusion that he “prefers older women,” where the truth is merely that he prefers complicated women he can respect and with whom he isn’t bored. Because his fear of phoniness keeps Monty out of New York’s bigger, brassier celebrity hangouts, he and Libby have been seen most often in smaller East Side bistros in the neighborhood of his tastefully furnished East 61st Street bachelor apartment. What they find to talk about, Monty and Libby don’t say. Some columnists have sworn they talk of love, others say they just talk.

In Hollywood he also used to date Natasha Lytess, who is Marilyn Monroe’s dramatic coach. But the real mystery woman of Monty’s life—because nobody can quite figure out where she stands with him—is the one who has been his Own dramatic coach. Mira Rostovskaya Letts, billed in her United States acting debut in The Seagull as Mira Rostova, is a petite blue-eyed brunette, at once birdlike and intense, whom Monty and Kevin have known for more than ten years.

Mira, born in Russia, was an actress in Europe before the war. Monty formed an immense respect for her from their first meeting. She was attractive, with some of the forlorn and frightened-looking beauty of a Luise Rainer, and she had the same kind of small, appealingly-accented voice. She also had brains. She became Monty’s coach, a sounding board off whom he could bounce all his deeply-felt urges to improve himself as an actor, a judge of all his experimental striving toward naturalness—which does have to be striven for.

She even went onto the sound stages with him, rehearsing him between takes, unobtrusively cueing him when he was on camera. Nobody on the set was ever quite sure what she did do, but as long as Clift came out good, nobody minded. Not until From Here To Eternity. Mira was absent then, some said at the studio’s request, and Clift still came out good—and stronger than ever—as Private Prewitt.

Mira Rostova had a lot to do with Monty’s doing The Seagull for peanuts this year, at a time when Stanley Kramer was hounding him to play in Not As A Stranger, when John Huston wanted him for Ishmael in Moby Dick, and when the late Leonard Goldstein was after him for The Leather Saint. They were waving up to $200,000 under his nose.

“Kevin, Mira and I had been promising ourselves for years that some day we would get together and do a play,” Clift said. “We read plays by the dozens,” (nothing new for Monty, who chain-reads screenplays and treatments while chain-smoking and chain-drinking cups of coffee, ever searching for just the right part) “but the only one we felt was right for the three of us was The Seagull. People like me need a live audience . . . Many an actor on top of the world and his career at the same time, does his soul good with a little comeuppance, which he gets most effectively across the footlights.”

Being a trio of perfectionists, Clift and McCarthy and Rostova couldn’t accept a standard translation. Night after night (usually in Monty’s roomy living room) they worked at constructing their own version, with Mira translating from the original Russian and the three of them worrying out each line of dialogue!

Add it up and undoubtedly there is affection between Monty and his Mira, but if it were ever to ripen into marriage it should have done so long ago.

Just where does all this leave the people who (in print) have been stubbornly trying to marry Monty off to one of the women in his life? It leaves them holding the bag. If he had been the eccentric they had mistaken him for, he might have rushed into marriage long ago. But he’s not really an eccentric, and certainly he isn’t a radical, despite his reputation as the pre-Brando Marlon Brando who went to Hollywood with one suit, two ties and a built-in sneer. (He happens to like grey flannels and grey tweeds, often dresses today as he did yesterday—but not necessarily in the same suit!)

On the contrary, he is one of the most conservative actors on either coast. It is conservatism, as well as seriousness about his work, that makes him fear losing contact with the “real” world where an actor finds his roots and inspiration. He feels that once he starts throwing his money around, or trades in his 1940 Buick coupe on a 1955 Caddy convertible, or gets to spending his time with famous people to the exclusion of ordinary people, he’ll be lost. Playwright Arthur Miller once put this feeling as one of “having to have a neighborhood around me.”

It was the same kind of earnestness that led Monty and Kevin to take seven months off and go to Europe with Mrs. McCarthy and their son Flip, so that Monty and Kevin could labor over a screen treatment of You Touched Me, the Tennessee Williams play that shot Clift to Hollywood and thence to stardom in Howard Hawks’ Red River. No studio ever bought their product, but they believe it was w ing anyway—because they had to.

“Monty’s that intense, earnest and dedicated about everything he does,” his brother says admiringly. “He could have been a tennis champion if he’d wanted to bother. He still goes to the gym all the time and keeps himself in great shape. . . . I think he’d make a great director; he has a director’s point of view and an uncanny sense of what an author means by a part. He treats every movie as if it were a play, working on his part the way he’d work on a theatre part and not settling for anything but his best.”

Deborah Kerr, who can be pretty intense herself, tells this story:

“When we were making From Here To Eternity all of us, naturally, were most excited by the work,” she recalls. “The book was gripping, and Danny Taradash’s script was wonderful. We all worked very hard toward understanding our roles. It was rewarding, but it was intensive work too, and at the end of the day we’d often discuss something else.

“One afternoon Fred Zinneman, Burt Lancaster, Donna Reed, Frank Sinatra and I were having tea. We were talking about Harry Truman, what kind of person he was, how you could dislike him or like him, but couldn’t ignore him or deprecate him at all as a fighter. Monty joined us when the conversation had already reached the pronoun stage. He pitched into it fervently for fully twenty minutes—before we realized that he was talking not about Mr. Truman but about Maggio, the part Sinatra was playing in the film!

“That was all he eared about then. He lived for that film when he was working on it. And bear in mind that he wasn’t just concerned with his own part, he was involved, deeply involved with the other characters. I’ve never known any actor who works so thoroughly and completely on whatever he does. We would sometimes relax, but Monty always thought of the film and of every aspect of it.”

It was because he admires thoroughness, sensitivity and directorial greatness that Monty sought out Vittorio DeSica in Italy a few years ago and applied for an acting job knowing very well that the pay, if he landed it, would be closer to off-Broadway scale than to his $150,000-per-film Hollywood price. DeSica said he’d think it over, and thanked Monty for saying all those nice things about Bicycle Thief and Miracle In Milan. Monty got acquainted with Cesare Zavattini, the happy, humane, gnomelike genius who writes most of DeSica’s screenplays, and convinced Zavattini that he was really serious about it.So Monty got the role opposite Jennifer Jones in Indiscretion Of An American Wife, the poignant vignette laid in Rome’s modern railway terminal. No picture part in the world would have made Monty happier, because only this one gave him the opportunity to sit at the feet of DeSica.

Before he branches into directing himself—and it appears plain that this is where he’s headed—Monty would like to do some comedy roles, either in films or on TV. He’d also like to play in The Emporium, a no-scenery play about a country store, if his good friend playwright Thornton Wilder ever gets through tinkering with it. Beyond that Monty would like to keep on making an occasional pile of Hollywood gold. “It gives a guy wings.”

But whether he’ll keep on winging about the world alone, or in the company of a wife, remains a baffling question. Maybe it even baffles Monty. Please, somebody, marry him! It isn’t right for a so nice to be alone so long when marriage could make him so much nicer!

THE END

—BY RICHARD L. WILLIAMS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1954

No Comments