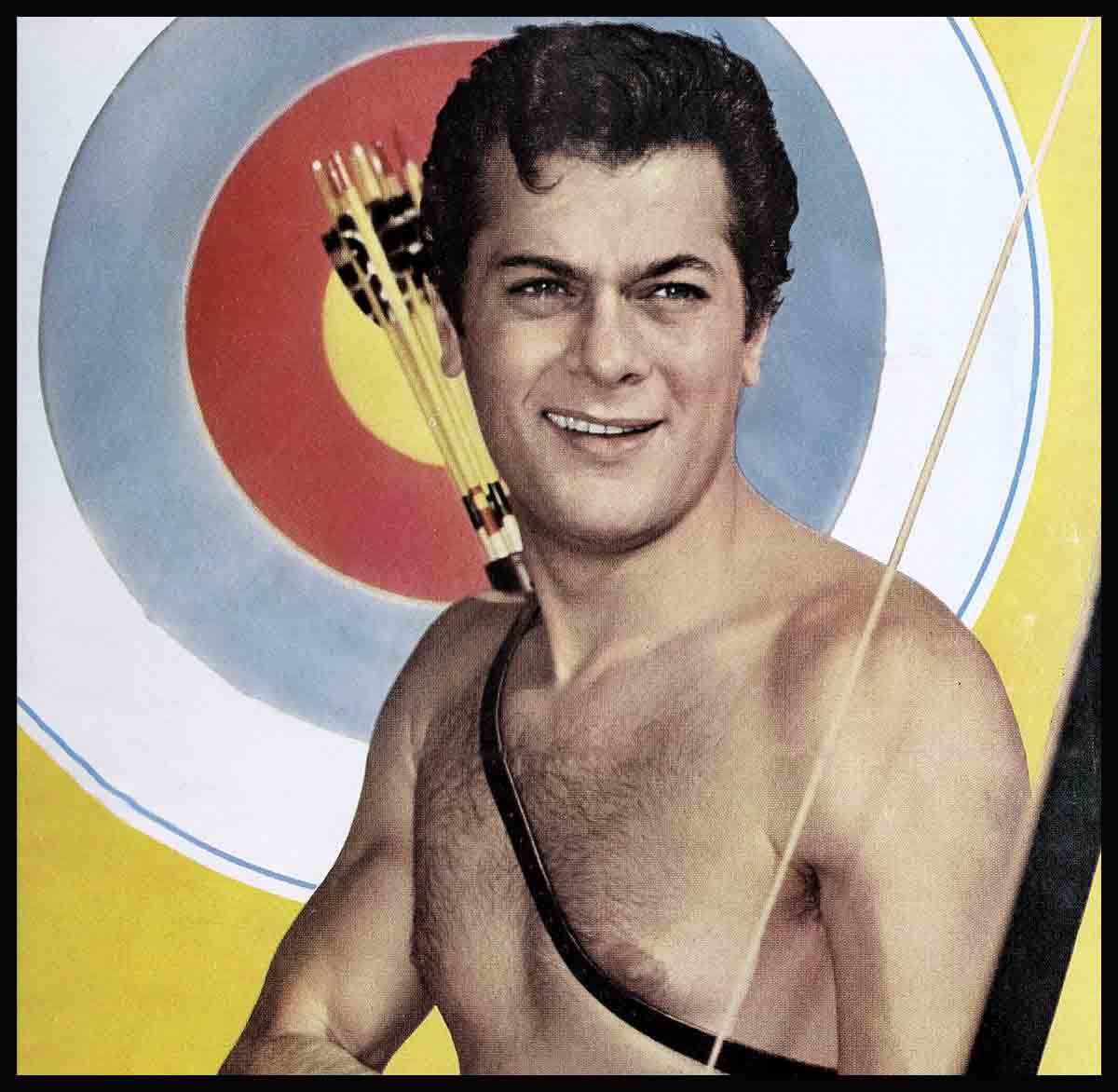

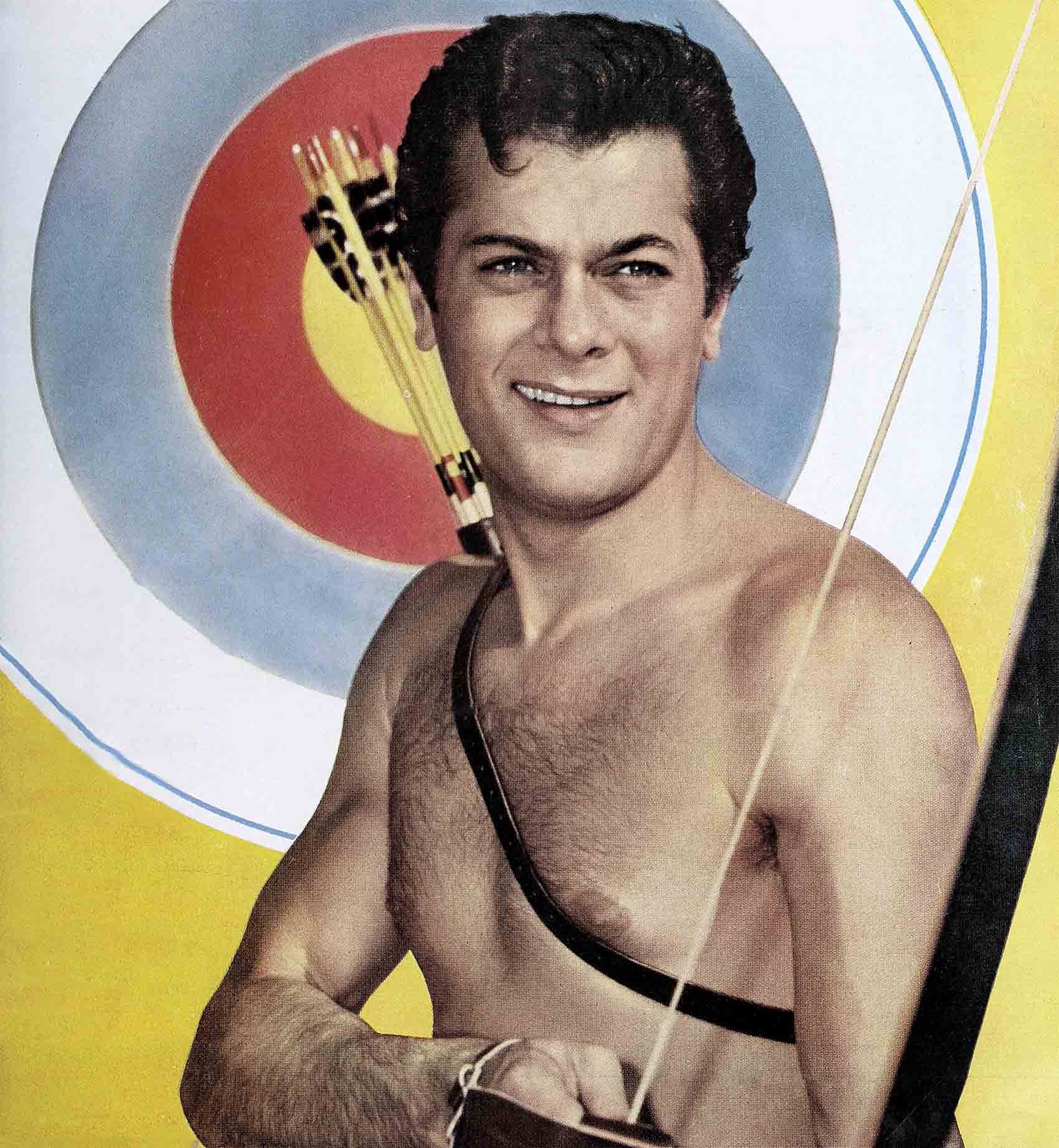

Boy Did I Goof!—Tony Curtis

“Last June third, I was thirty years old—and I never dreamed I should live that long,” said Tony Curtis. “The next day was my fourth wedding anniversary. A crazy guy like me, married four terrific years! Later that same week I signed to make a picture in Paris with Burt Lancaster and Gina Lollobrigida because, as my agent said, “The chemistry is right.’

“Chemistry! What was with chemistry and a kid who used to be called Bernie Schwartz? What was with that crazy ganef who in school in New York’s slums refused to learn because he wanted to be ‘free’? How could such a week come to a wild Hungarian who practically didn’t speak a word of English until he got beaten into it?

“When I saw those representatives of a billion-dollar agency walk into my dressing room and tell me that the plans for my studio, U-I, had been juggled around and the Lancaster schedule had been juggled around, just to fit my time, I flipped. I was not thinking first of the wonderful time Janie and I would have living three months in Paris. I wasn’t thinking I’d become a big man now. I wasn’t even thinking how lucky I was, that such things could possibly come true for me.

“No, I was just wondering if I knew enough to play the role in that picture, ‘Trapeze.’ And don’t misunderstand me, that wonder wasn’t any humility. Because humility is one of the things I’ve had to unlearn about. Being ‘free’ is one of the things I’ve had to unlearn, too. And another is facing up to the fact that you won’t always be as brave, or as honest, or as worthy as you want to be. Those are things I’ve had to unlearn, along with the realization that such a failure on your part is no crime.”

Tony talked, sitting in his new dressing room, which is really a glittering sight. Originally, at U-I, he had a small dreary place. Then he graduated to sharing space with Jeff Chandler. But now he has what’s practically a small house, as big as many young couples’ first home, with a charming living room, a small inner room that could be for sleeping but which Tony uses as a studio office, a fine kitchen and a bath.

Janet’s in “Pete Kelly’s Blues” and “My Sister Eileen”

Getting back on the subject, “I think the first thing I had to unlearn,” said Tony, “was that your ideal for yourself isn’t always necessarily attainable.

“I remember when I was just past seven. I was a real retarded kid. I was too small for my age, and I spoke no English because I never heard any at home or even in our New York neighborhood. For four blocks in every direction from where we Schwartzes lived there were nothing but Hungarians, most of them as freshly over from Europe as we were, most of them as hungry and poor.

“Then one day we moved. One day? We were always moving because my father’s tailor shop didn’t very often bring in enough for us to pay the rent more than a month or so, and every time I moved into a new place it was the same old story: I had to take a beating from the kids on the block. I was too small to defend myself. I was a new kid and Jewish. So I was always in for it.

“Only this time I determined to be brave. I knew I’d be knocked around, and maybe I’d crawl home, half-conscious. Only this time I knew, I was going to be fearless and stand up to it as long as I could.

“So I started down the tenement steps and there was just one kid waiting for me. But how he was waiting! He was just staring me down and he was twice as tall, twice as heavy as I was. He was completely relaxed, except for his tightened fists which looked harder than the pavement.

“For all of one second I looked him fearlessly, bravely in the eye. He looked me right back, just waiting. I looked again, and then I fled, straight back up the stairs, straight back to my mother.

“Sure, I was a coward, and I knew it. But I knew I’d learned something. Or rather, I’d unlearned about fearlessness. Right then I discovered that merely being brave, merely being fearless isn’t enough. It can even be stupid.

“Almost at once I started trying to acquire some muscle and brawn, because that way I was going to get ‘free,’ be able to do exactly what I liked, and nobody would be able to push me around ever. It says here. Then I didn’t grow up tall enough to suit my dream of Bernie Schwartz, great free man, I did all sorts of things like delivering ice, so that my arms developed and my shoulders broadened, meaning that when I went into a street scrap I could sometimes come out the winner.

“But at that time the one muscle I never considered developing was my brain. That took too much discipline and, to be free, I had to be an anti-discipline man. I didn’t intend to submit to teachers and lessons. No, sir. I was going to stay untamed.

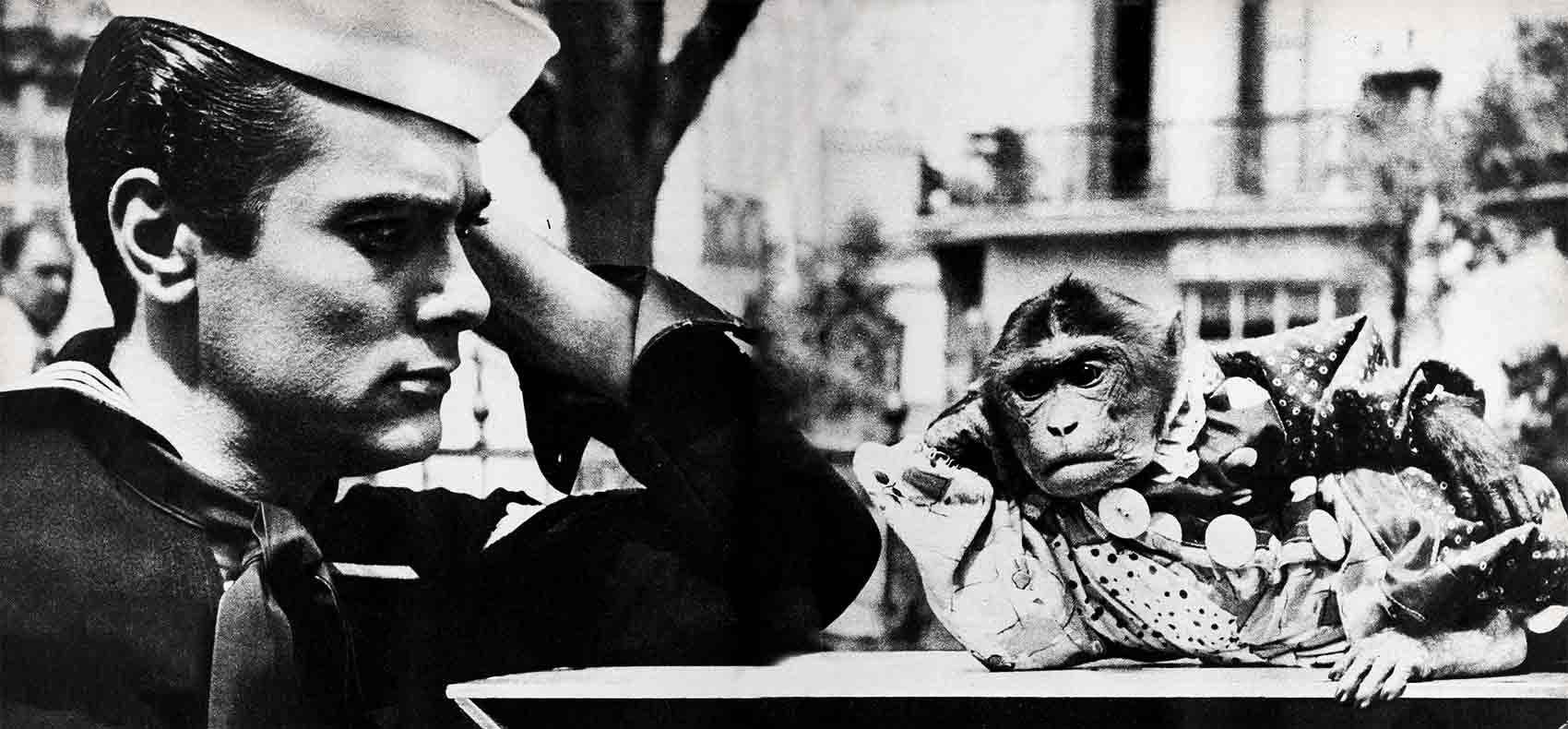

“It wasn’t until I was seventeen and in the Navy that I wanted to unlearn that no-discipline bit. The orders I had to take or get my block knocked off, I took, of course. But the day I saw a different perspective was when an officer came round and asked which of us gobs would like to be officers. My hand shot up so fast I nearly pulled my arm out of the socket. The idea of wearing gold braid, of: being constantly saluted, really reached me.

“So they let me be an officer candidate—for all of one class. Then the character who was examining my I.Q. looked at me and said, ‘How can a bright kid like you be so dumb? Why, you can’t add seven and four.’

“That wasn’t strictly true. I could add seven and four—but not easily. So I went right back to being a gob again, and for the first time I comprehended how my ‘freedom’ was merely earning me less freedom, that is, more orders, more being subject to other people’s commands and demands.

“So when I was out of uniform, I started to correct that. I hustled around, trying to get my diploma from high school. But I soon goofed. I told myself I was now too old to study.

“But right about then I got my big break, the chance at a term contract with U-I. Oddly enough, I landed on the lot on my birthday. It’s weird how so many of the important dates in my life have coincided with my birthday.

“This one was my twenty-third birthday, and I was quite disappointed with myself because I’d read in the movie magazines how Tyrone Power had started when he was twenty-two. I’d missed it by a day! To my mind, this put me a year behind in the race for fame, but I actually didn’t have too much doubt that I’d soon overtake Ty and overtake every other actor, too.

“That’s when I discovered that the opulent one hundred dollars a week I was to start with turned into thirty-five dollars when all the deductions, agents’ fees and the like were out of it. That’s also when I found out that while everybody on the lot was very pleasant to me, nobody was exactly dying till they got me into a picture.

“It was a funny thing. I’d learned just the faintest bit about acting in New York when I got a chance to play in Clifford Odets’ show, ‘Waiting for Lefty.’ I had to smoke in that, and I’d never smoked in my life before. So I nearly smoked myself sick, for weeks before, learning to handle a cigarette naturally.

“So there, at U-I, I tried to study everything. I lived in a sort of boarding house, with a lot of other young actors, and we talked nothing but ‘shop.’ And finally I did get into ‘City Across the River,’ not the lead, nor the second lead, or even the fourth—the fifth. Most of the time my back was to the camera, yet the miracle happened and a few people noticed me and wrote in to the studio and the critics were unbelievably kind.

“I zoomed, emotionally. And deflated again, as the studio continued to ignore both me and my notices. Finally, I got in a second picture, which starred Yvonne DeCarlo. I delivered a telegram to her.

“I got one fan letter from that. Just one, but I’ve still got it. It said, ‘Who was that boy who delivered the telegram? Why doesn’t he star in a picture?’ At the time it arrived that much faith in me was very important.

“You see, a director—almost any director—is the toughest foreman or overseer. He has to be. He has to get his expensive product into the can as quickly as possible or he will get fired, and we actors are the raw material he has to deal with. So he criticizes you—usually in front of a bunch of people—and you learn to take it, even if you hate it. He criticizes your walk, your talk, your height, your coloring, your personality and your stupidity. It’s brutal, and maybe sometimes it is unjust, just as it is in other jobs. But if you can learn to take it, just as you must in other jobs, you come out strong.

“That’s what I meant when I said, thinking about this new picture ‘Trapeze,’ I wasn’t thinking in humility. I don’t believe in this so-called humility. As you begin to learn a little, you get perspective and learn how little you do know, and how much more you must know, and that you’ll never know enough. But the very way you know that is because you already know more than you did. So you aren’t ‘humble.’ For the first time in your life, you are beginning really to know something and, therefore, you have more faith in yourself.

“Or at least this was true with me. I’d ditched that freedom gag long since, and I went gratefully to the U-I training school and tried to rehearse all my poor diction, all my corny mannerisms out of me. I came to see myself clearly enough to realize I was cut from the material of children of my environment—too tough in some ways, too sentimental in others, too uneducated all the way around. But nothing was stopping me from learning.

“Falling in love with Janet, getting her to marry me was a terrific step forward. A good marriage changes the whole pattern of any man’s life—and that Janie and I have. Sure, we have quarreled. Sure, we do quarrel. I can come home dragged as the next guy and take out my fatigue on her—or vice versa. But the quarrels are only part of the necessary way of getting to know one another. Love is what makes you grow, and we are in love.

“As a very pleasant matter of fact, I had less to unlearn in love and marriage than anywhere else. My folks had had Janie’s and my kind of marriage, too—full of laughter, color, enthusiasm and a few rousing rows. Her folks have had a great marriage also. I did have to learn more neatness, more punctuality, less impulsiveness about what I wanted to do. Or, I was unlearning that old ‘freedom’ snare again. But it was a lot to give and take, and my girl having to learn to relax a bit, too, and not be quite so on the dot and on the dime all the time.

“Now I own my home. I know I’m not going to get arrested by the cop on the beat because I don’t know my way around. And I’m in love with my job, which happens to be acting. And here I am planning months in France, so that maybe a little language and even culture will rub off on me.

“It’s great, and the chief thing it all unlearns for me is that being ‘individual’ is for the birds. You’ve got to get with life, get with other people, get with the sums of knowledge that are just there for the asking.

“That’s kicks!”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1955