Who Says Beautiful But Dumb?

If I were asked to select the smartest screen beauty I know, I would pretend to be deaf or retire behind the Fifth Amendment. A man can get a terrible bump on his head falling off a limb like that.

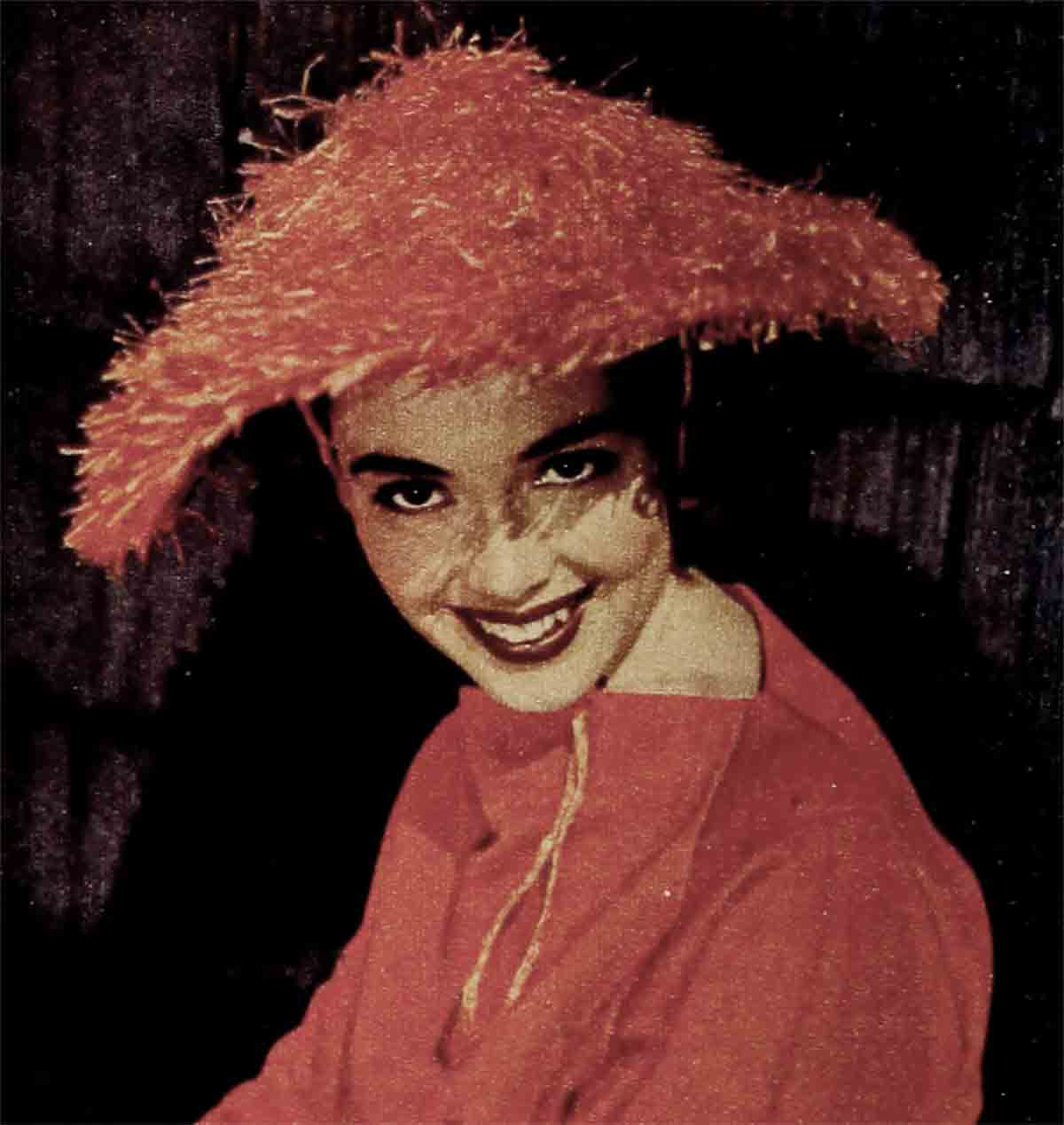

Certainly one of the smartest is Esther Williams, whom I happen to be directing currently in Metro’s Jupiter’s Daughter. I don’t know how much you know about Esther’s off screen activities, but I can tell you they are extensive, the tireless work of a good business woman and a wonderful wife and mother. The Ben Gages, of whom Esther is half, are seeing to it that their children will be off to a flying start.

Probably you know about some of her business ventures—the filling stations, the West Los Angeles restaurant (which began modestly enough and is now breaking in big name acts for Las Vegas) and the partnership in a nationally known bathing suit business. She has on paper the blueprint for the time she will no longer be in pictures.

She has worked out a personal appearance routine, beginning with a “dry” aquacade. This she will try out in Vegas in October. In it (I am a trifle vague on this myself, but Esther has it mapped to the last detail) she will do all the things out of water that she ordinarily does in it. Presumably this does not include a dive from a ten-foot tower onto a nightclub floor, but the rest—yes.

I see no immediate danger of Esther’s departure from our midst—indeed Leo the Lion likely would burst his appendix if she decided to check out tomorrow—but none of us lasts forever. Esther has the fine intelligence to be conscious of her limitations. Some recurrent trouble with an eardrum may have spurred her decision to design the future. Whatever it may be, Esther Williams’ mind never stagnates for a moment.

Beautiful? Assuredly. Dumb? I wouldn’t say so.

Then one might have said Ann Blyth had everything—certainly enough that she could rest on her oars, had she wished. Beauty, talent, great popularity, a handsome, successful husband, a loving family. But for Ann—and for so many like her—complacency does not exist. She wished to use her charming singing voice on the screen, to add a new dimension to an already versatile personality. It meant a tremendous amount of work, but what of that?

Let me get this point in now: The clearest mark of intelligence in the successful screen star is the absolute willingness to work, the recognition that without that willingness, one’s career is in genuine danger. Laziness is the unforgivable stupidity and the majority of those who have failed have failed because of it.

The film star’s life is not an easy one. Besides the constant battle for self-improvement, it is a life of appalling hours and often appalling drudgery. She gets to the studio about seven, is busy until nine when she arrives on the set, ready to go. The actual shooting creates strain, tension and stifling boredom—the waiting period when sets are struck or cameras realigned. During breaks, she may be called on for fittings, interviews, rehearsals, one of a hundred related chores. She is always studying. When she gets home she’s dead tired—sometimes too tired to eat more than soup with comfort. But she still has the next day’s lines to go over.

I contend that no woman beautiful but dumb would subject herself to such an ordeal. Your answer might be that she’s too smart. But I do not think so. The rewards for such rigorous, unstinting application can be great, both the material ones, and the tremendous compensation found in doing what one likes to do as well as one can do it and with every last ounce of energy.

I may be prejudiced but that, to my mind, is smart. It is more than smart; it is an order of high intelligence, the artist’s sort of life.

In Annie Get Your Gun, another directorial éclair of mine, Betty Hutton, had to learn to shoot and shoot so well that there would be no suggestion of fake. We wanted it so that Annie Oakley herself would have approved. Skeet is a hobby of mine so I’m pretty fair at it. I took Betty out to the back lot and put a gun in her hands. She handled it at first as though it were a golf club with a cobra wrapped around the shaft. But in a few days she was knocking the tops off bottles. I’m not fooling you. She gave hours at a time to nothing but shooting and became a crack shot. For what? Just for a few scenes. Conceivably, a double could have been used in most of them. But doing it that way is not what has made Betty Hutton what she is.

Look at her now. She’s in a fascinating phase of her career—nightclubs and other personal appearances—helping to get vaudeville back on its feet. She is not doing it for peanuts. If she feels she made the move at the right time, who am I to argue with her? She’s too smart to have made it any other way. As I understand it, she didn’t like the pictures she was getting so she took her case to the country. When she comes back to Hollywood, she’ll be writing her own ticket.

Rosalind Russell, a truly brilliant woman, did the same with that superb New York show, Wonderful Town. So did Judy ‘Garland, an incredible talent.

Jane Powell, one of the sweetest and most intelligent mothers I have ever known or seen, will be striking out on her own one of these days (Las Vegas last year was an impressive preliminary) and so will Kathryn Grayson.

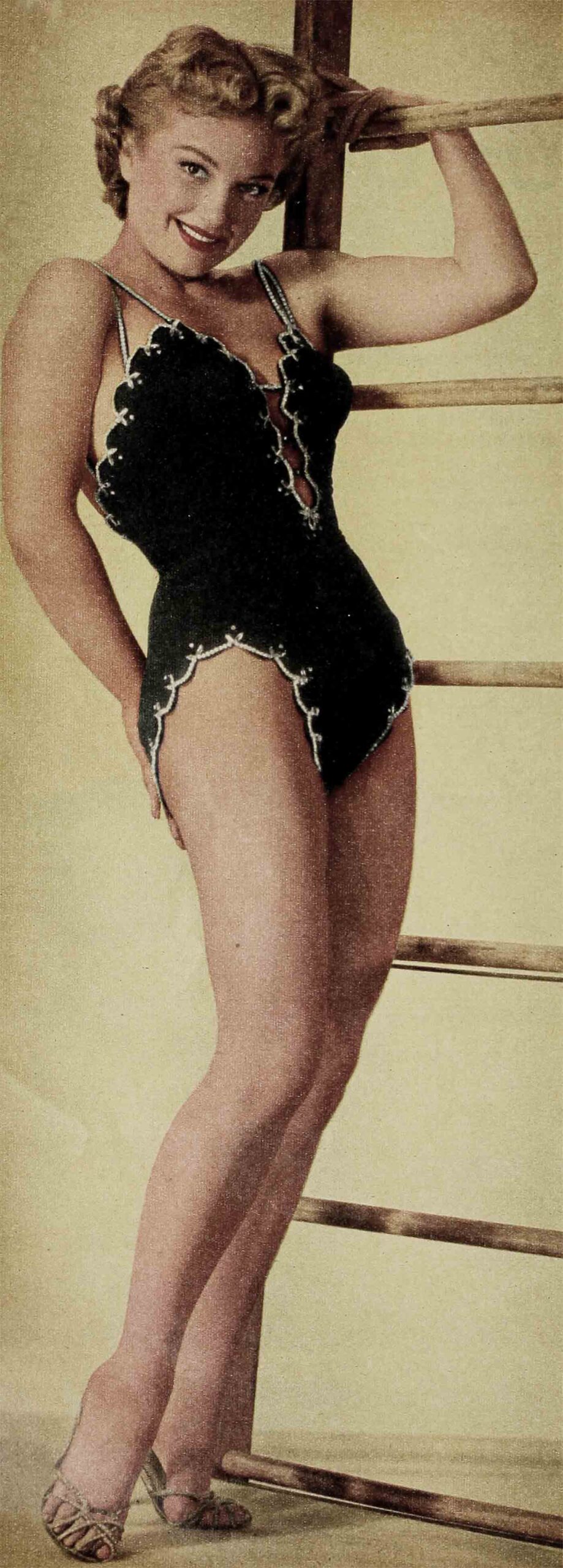

Kathryn’s Las Vegas engagement wasn’t just a routine, agented deal. Katie set up every last detail herself. They wanted her, of course, but she took care of her own end right down to the way the costumes should be stitched—and that niggling matter of dragging down $90,000 for three weeks.

She wasn’t sure whether a classical program would be welcome in nightclubs. Normally the procedure would have been a kind of sneak preview on a modest tour. But that wasn’t for Katie. She let Vegas pay for her gamble—what better patron would there be?—and then went on to the double satisfaction of proving that supper clubs did like her. Very, very much.

The point of Kathryn’s beauty has been satisfactorily settled long ago. Now you can see what else there is.

Jeanette MacDonald, like Judy Garland and Betty Hutton, has a feel for live audiences and is on the road much of the time. But she can’t be said to leave things to chance, which is intelligence on her part as it would be on anyone else’s. I am quite impressed that she carries with her her own lighting, setting it up in each new auditorium. And I am very much impressed by the fact that in one night recently, she drew down $17,000. Beautiful but what?

Mae West has a similar gimmick for her tours, but on a very special scale. Miss West still is a big apple of the public eye and after each of her performances large numbers of her fans swarm to her dressingroom. They’re entirely welcome—but not until Mae has lighted herself at her dressing table with a special battery focussed and adjusted for Mae and Mae only. Thus she makes sure she looks as striking off as she does on—and Mae, believe me, is still very much something to see.

You may tend to look down your nose a bit at capers like this. But I don’t. I speak here from a rather insular point of view, as part of the film industry, but I think they’re great. We’re showmen out here, and showmanship is as much our business as body-lines are Henry Ford’s. I want to cheer when Marilyn Monroe makes one of those entrances, when Terry Moore cuts loose with her latest nip-up, when Joan Crawford never for a second behaves like less than a movie star—and would you say that dumbness has kept her on top for twenty-five years? Janet Leigh, a prime example of the hard-working, level-headed girl, continues to consent to those eye-filling picture layouts. That’s a piece of this business, and it is a very vital piece. It’s wonderful—and it’s smart!

Then there are samples of what I think of as cool, no-nonsense intelligence. They may not seem like much as isolated episodes, but it’s trouper stuff, little victories of poise and common sense over the sort of upset that unstrings a low-calibre brain.

I directed Ava Gardner in a scene in which she was to fondle a monkey. It was rather long but she played it without a hitch. This was noteworthy, for throughout the sequence, the monkey had been chewing steadily and painfully on Ava’s forearm.

She could have stopped the action immediately. But it would have (1) cost money, (2) necessitated a re-take.

Ava declined to be heroic about it. A re-take, she explained, would simply have meant more chewing, so she wanted to get it over with the first time.

If I had been chewed by a monkey, I never would have thought of that—and I haven’t the excuse of beauty to defend my short-sightedness.

You may recall the cat in Cass Timberlane. Now Lana Turner is kindness itself to animals but she has, like many persons, an aversion to cats. She feels about them much as some people feel about snakes. There is nothing to be done about it. Judy Garland is that way about horses.

That presented us with an impasse, of course, since Lana was one of the stars of the film, and she was called upon to lug that cat around. I defy you to this day to read the slightest trace of fear or revulsion in her comportment throughout the picture.

If Lana were feather-brained, she might have refused to touch the animal or succumbed to hysterics. But she swallowed an authentic phobia and went ahead with her job.

No one has ever suggested that the magnificent Ethel Barrymore is in any way dumb. But she plainly is beautiful and she is incontestably an actress. One of my favorite stories bears on my point.

I had done some early scenes with Miss Barrymore and afterward I asked if she would like to see the rushes to determine for her own satisfaction whether she was happy with the way she was screening.

She asked me, “Were you satisfied with them?”

I said I was.

“Well, then,” she said, starting to walk away.

“But, Miss Barrymore!” I called to her; “Aren’t you curious in the least about your performance?”

“Mr. Sidney,” she said, “I have appeared in many, many plays, and have yet to see myself in one. Why should I start now?”

On the metro lot, we have yet another highly intelligent young woman. Her mind dominates her moves and decisions which usually are cagey ones. She is witty and cool, well-balanced and well-read, humorous and highly receptive and sensitive to direction. All this proves is that she is not dumb. It does not establish her beauty. But as one who knows every plane or Elizabeth Taylor’s face, I will leave that to you, confident I am in safe hands.

Finally, real stupidity, dumbness, would come through on the screen; not mock-dumbness in character parts, but the truly vapid expression of low-cell mental equipment.

So why should anyone be surprised that film beauties are not dumb? Intelligence registers vividly and on occasion it is ever misnamed “personality.”

The faces of the new crop are alive with intelligence. This is an integral part of their beauty, not a contradiction.

Beautiful but dumb—all these lovely women of Hollywood? Not a bit of it. Au contraire, as they were saying in high school French the last I took note of it.

THE END

—BY GEORGE SIDNEY

(Lana Turner can be seen in MGM’s Betrayed, Elizabeth Taylor in MGM’s Beat Brummell.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1954

No Comments