Hayley Mills With Elastic Abilities

It was her first ball, and she wasn’t really supposed to be there. At the last moment, her mother had scooped her up, scrubbed her clean and swooshed a party dress over her head. In the car, there were hasty instructions on how to behave. Then, all ribbons and ruffles, she watched wide-eyed as her older sister Juliet presented a bouquet of flowers. Soon it was her turn. Taking her skirts in hand, she bent low in a curtsy, just as she’d been told. Then she looked up, beaming. Princess Elizabeth—now Queen of England—beamed back.

After that, Hayley Mills did just what any other normal five-year-old girl would do at her first ball. She spilled a glass of orange juice all over the front of her dress. She was quickly taken home. It was years and years before she was allowed to meet another princess.

Ten years later, at her sister’s wedding, Hayley had the orange juice well under control. It was she who was spilling over. Some of it was the excitement of Juliet’s getting married. The rest was that, at fifteen loping headlong into sixteen, Hayley had a secret. She knew something that most girls her age don’t know. It was something that many girls, whatever their age, never know—or else they find out when it’s too late.

Photoplay heard about the secret and determined to find out what it was. We sent a reporter jetting across the Atlantic to see Hayley, and this is the story she brought back:

The minute I saw Hayley, at the Pinewood Studios just outside of London, I got my first clue.

She was sitting on a volcano.

It was phony. I asked about it, just to make absolutely sure. It was a bare rocky mountain, about four stories high, and the open mouth at its peak definitely looked menacing.

Hayley was real. I didn’t have to ask about that.

It was due to explode the next day, for a scene in Hayley’s new movie, “The Castaways.”

She had exploded five years and five pictures before, in “Tiger Bay.”

As for me. I thought I’d explode any minute. Laughing. This girl is too much.

Her parents—actor John Mills and actress-author Mary Hayley Bell—must have suspected that the minute they saw her. They must have taken one look and known that with this girl anything might happen. Anyway, as if to cover themselves no matter what happened, they gave her a whole string of names.

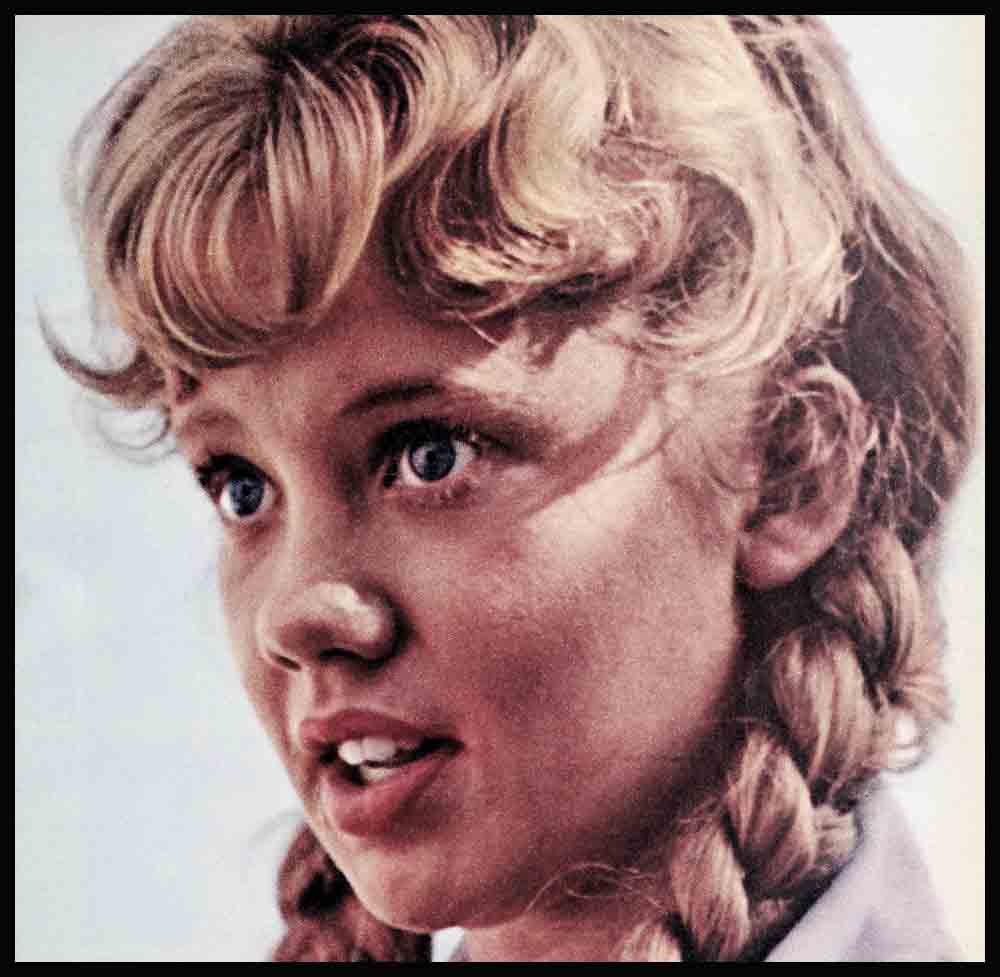

Hayley counted them off for me on her fingers. “Hayley Katherine Rose Vivian Mary Mills.” on the “Rose” her rubber face went into action: “Ugh.” She admitted that that many names was unusual. Her sister Juliet, four years older, has just two, and her brother Jonathan, four years younger, has just one name to his name.

I pulled up a rock and sat down. As we talked. Hayley stretched out her legs, wriggled, then tried tucking them under her. She couldn’t sit still. It wasn’t the volcano, it was Hayley.

She’s a study in perpetual motion—especially her face. She was complaining that people were beginning to exaggerate about her. “They make too much of my pranks,” she said. She admitted there had been a few. She rattled them off. I couldn’t write quite fast enough, but I got some of them down.

2- She had her hair done specially for the wedding, and looked the picture of poise as she sat under the drier. But she told us later, “I was really more nervous than Juliet!”

The master prankster

Tike at school. She’s just been graduated from Elmhurst, a boarding school for girls. Her mother had picked that one because it wasn’t the usual athletic kind of English girls’ school; they had ballet instead of cricket. Otherwise, Hayley made it sound like the kookie kind of place in “The Belles of St. Trinian’s.”

“All the girls wore uniforms,” Hayley said, “gray suits and coats or gray skirts with a blue blouse or sweater. And blue berets. The berets were the giveaway; anyone seeing them would spot you for a boarding-school girl. You were never allowed off the school grounds, even on weekends, except by very special permission. Of course, we managed.”

Hayley would ditch the beret, wear the sweater and skirt that could be anybody’s clothes and sneak into town to the sweet shop. “Once a friend and I managed to sneak out to meet a couple of boys down by the trees. And at boarding school, boys were even more forbidden than sweets,” she told me. “We were complaining about our school and they were complaining about theirs and we didn’t even hear the teacher coming along until she was practically right down on us. My friend was caught—and fined—but I got away.” Evidently Hayley can outrun any teacher. But it was an historic occasion in its own way. It’s the only time Hayley ever ran away from anything; usually, she’s running toward.

4- Hayley stood with Juliet and Russell in the receiving line.

Monsters from outer space

“Juliet pulled the best prank,” she gallantly confided. “I was in my room at school, trying to get the algebra done. Algebra,” she moaned, “the very mention of the word and I’m gone. Then there came a knock at the door and there was a teacher with this little old lady in a funny hat and all muffled up in a big fur. She had a quavery voice and she kept dabbing at her nose with an enormous lace hanky. I didn’t recognize her, but she said she was one of my aunts. Well, we have a big family. and if she was willing to take me out of school for a few hours, I was willing to go. I was told to come downstairs and all the while the teacher kept telling her what a dear girl I was. That’s the way they talk when your family’s around. When there are no relatives, they’re more honest—then we’re more like monsters from outer space.

“I waited while my aunt had an inter- view with the teacher. She wanted to talk about her own little girl, she said. Perhaps she’d come to the school, too. In the middle of the interview, my aunt began to shake all over, as if she were having a fit. Then her hat fell off—she was laughing so hard—and there was my sister Juliet. She’d even had me fooled—she’s a marvelous actress. But the interview was too much for her and she cracked up. I expected the teacher to he furious, but even she had to admit it was funny, so she let me out anyway.”

As Hayley talked, there was something about her that reminded me of nobody else. Not Debbie. Not Sandra. Not Tuesday. Except, of course, she has one thing in common with another child star from England. Like Liz Taylor, she has a desperate passion for animals.

“We live in the city half the time, in a flat near Leicester Square,” she told me, “and the rest at the farm. It’s about forty miles south of London and the house is fourteenth-century. Of course, we’ve brought it up-to-date, plumbing and all that.”

She’s happiest at the farm—except about the hunting.

“We only kill birds and animals that are varmints or scavengers,” she explained. “Still, it makes my heart sink when I watch a bird fail—dead. When I was little, I tried to talk Daddy out of it, and he’d try to explain that some birds ruined the crops and some animals dug holes that made the horses stumble and break their legs. But I felt I had to do something about it.

“Mommy and Daddy would go out hunting early in the morning, and I was supposed to be too young to go along. But I’d sneak out of the house and follow them, still in my nightgown. I’d hide behind the bushes until I saw Daddy taking aim at a flock of birds. Then I’d jump up and down, clapping my hands together as hard as I could and shouting at the top of my lungs, ‘Bang! Bang! Bang!

6- Hayley and Jonathan shared a big secret at the reception! It was held at the Mills’ farm not far from the little church where Juliet and Russell were married. “I love that little church,” Hayley told us later. “I’d like to get married there, too.”

Her father would miss his shot and be furious, but by that time the birds were warned and had flown off. It was sort of a one-girl SPCA. To protect the horses, which she loved best. Hayley decided it would take several girls.

“I got all my friends together in a secret society,” she said. “We called it USH.” That stood for Unlawful Slaughter of Horses.

Once, as president of USH, Hayley found out about a mare that was going to be destroyed because of a broken leg. She begged her mother to save it, and Mary Mills, from whom Hayley must get much of her tender-heartedness, bought the horse and nursed it back to health. Mary took a lot of teasing from her own friends about it, so later, when the mare had a foal, it was named Mary’s Folly. The foal grew up to be a famous race horse.

“Once a photographer, wanting to take a picture of the horse, phoned the Hat.’’ Hayley told me. “‘Where’s Mary’s Folly?’ he asked the housekeeper. She was sure she understood. She told him, ‘Hayley’s at Pinewood Studios!’ ”

When she was younger, Hayley used to bring a bit of the farm, usually a pet mouse, to the city with her. “Mine was Stanley.” she said, “and Juliet’s was called Elsie. We carried them in our pockets wherever we went. Once, in a big London department store, they got loose. It was a long time ago,” she hedged, “and I don’t remember if we did it on purpose or if they just jumped out while we were trying on clothes. But all the women began shrieking and it was panic. We had to get down on our hands and knees and crawl around under the racks and counters till we found them again.”

Hayley’s concern for living things extends to human ones, too. “I’m very taken up with the bomb,” she said. “It’s terrible, it could be the end of everything. Did you know I was asked to be on the Committee of 100?” She told me about the group, led by Lord Bertrand Russell and many of England’s top intellectuals, that had been staging pacifist sit-down demonstrations. They were trying to bring about disarmament. “I was flattered that they asked me, and I really wanted to join them, too. Not that I was so anxious to sit down on the cold pavement and maybe be dragged across it like a sack of potatoes by a policeman, but my God,” she almost pleaded. “I felt we just have to do something. Then I had to realize that it might embarrass Mommy and Daddy and I knew Mr. Disney wouldn’t like it. So I didn’t join. But I still get letters from them and pamphlets that say things like: ‘Doom is near but don’t despair, come sit down in Trafalgar Square.’ ”

She paused for the first time in her rapid-fire of talk. I went on to another question. “Do you daydream a lot?” I asked her.

“Why did you ask that was I wandering?” She looked a little guilty. Then she said, “The bomb. I guess I even daydream about it.”

She was discovering that it was even harder to save people than birds or horses. “Do they think about it as much in America?” she asked. “I loved America when I was there,” she told me. “Especially Disneyland and the drive-ins.”

She met a lot of boys in America, but she didn’t go out with them much. “I was more interested in horses at the time.” She thought it over. “I must have been crazy!

“But while I was in Hollywood, I actually saw Elvis Presley,” she recalled. “We were driving along, and this big white Cadillac pulled up alongside us at a stoplight. We saw lots of Cadillacs in Hollywood and we always looked inside to see who was in them. Well, there he was. Juliet and I thought we’d die. He was sitting inside, smoking a cigarette, and there were some other men with him, all dressed in black. He’s a terribly good-looking man. I couldn’t take my eyes off him. Then the light changed and that was the end of it.

“But I almost met him another time, too. Mommy and Daddy were going to a party and Juliet and I were invited. But we had something else to do, and besides, we thought it would be just an ordinary grown-up party. Wouldn’t you know? He was there! And Cary Grant! Mommy told us about it at breakfast the next morning. Juliet and I kicked ourselves for weeks.”

I asked about the boys she dated.

“My boyfriends are all men”

“My boyfriends are all men,” she said. That meant they were at least eighteen. “They have lots more to say than boys, and they’re more fun. Boys tend to get embarrassed. And I hate show-offs or loud boys. And phonies, that’s the bottom of the street.

“I’d like to find someone as wonderful as my father—if that’s possible.” She wrinkled her forehead as if she thought it wouldn’t be easy. “He’s so understanding and patient. And so funny. I mean,” she summed up, “he’s all right.

“I think teenagers are the same where-ever they are,” she went on, “but we’re a little different about dating in England than you are. We don’t usually start so young; Juliet wasn’t allowed to date till she was eighteen! Mommy and Daddy are being more lenient with me. I could wear lipstick at night when I was fourteen. Still, they’re tricky about letting me go out. They want to know the people I go with. On weekends, I can stay out as late as I want, till one or two o’clock. Weekdays they want me back by about ten.

“We usually go out in a gang. What I like best is to go see a movie and then go tramping around Soho looking at all the restaurants and shops. Then we end up finding a place to have coffee. We usually pair off, but I do think girls should put in when they’re out with boys. That’s what you call going Dutch treat.

“And I love parties. Usually I like to wear casual clothes, straight skirts and sweaters or suits. But once in a while, I love to dress up. It puts you on a pink cloud. Last weekend I was at Cambridge visiting my cousin, and there were just lots of parties. It was marvelous. Sometimes, at a party, I feel shy if I don’t know anybody. Then if the other people are shy, too, it’s the end. But up there my cousin introduced me to everybody. I met Prince William of Gloucester.” She rolled her eyes. “He’s divine.”

I’d asked her what she’d like to do most in all the world—if money and parents were no objections. She didn’t hesitate. “I’d like to go to a university,” she shot back. “Cambridge!” She looked at me conspiratorially. We both knew Cambridge was an all-boys school—mostly.

She admitted that she’s always getting crushes. “I’m suffering at the moment,” she confided. “Unrequited love.” She agreed it was a problem if you liked someone who didn’t like you back. “Any girl who chases a boy is really the bottom,” she said. “But there are things you can do about it. There are different tactics for different boys. For instance, if he’s a quiet boy, you just sort of go and sit down next to him and talk to him— quietly. You can bring him out of himself. But I’d never call up a boy unless I had something to ask him. You know, if I had an extra ticket to the theater or an invitation to a party. It’s different about the phone here, too. In America, I was always on the phone. For hours. It used to drive Daddy crazy. He’d pace up and down in front of me, wringing his hands and saying he was expecting an important long-distance call.

“In England, we don’t talk that much on the phone. We just get together and talk in person,” she said. “That’s how I came to be in the movies. One of Daddy’s friends drove down to the farm to talk.”

They were talking business. John Mills was already signed for the movie “Tiger Bay.” They still needed to find someone for the young boy’s part. “Instead,” Hayley said, “they found me.” While they were talking, the visitor’s eyes kept wandering over to Hayley, who was playing nearby. He asked if she’d ever done any acting or had had a screen test. He was told no, except for little plays the family did together at home. Her father agreed to a screen test for Hayley and, once they had a look at it, the part was promptly rewritten for a girl.

“I’d always said I wanted to go into acting, but I only said it because Daddy was in it,” Hayley told me. “Actually, I was afraid of it. What I really wanted was to have lots of horses and run a livery stable. And some day I wanted to be a mother.

“But in our family, when you get to a certain age, if you can act, you just do. Juliet’s on the stage, and Jonathan was in ‘Parent Trap’ with me. Someone in the movie says to him, ‘You have red hair—what color is your sister’s?’ And he answers, ‘Gray!’ He’s like that in real life, too. We used to have great fights and pull out chunks of each other’s hair and bite and roll all over the floor. But now that we’re older we only fight with words. He’s a monster.” Then thinking about it, “No, he’s really divine—most of the time.”

Once she started to act, Hayley found there was nothing to he scared of. “She’s instinctive,” her father says. “She’s absolutely got it. It’s wonderful to see it come out.”

Hayley doesn’t absolutely agree. “I don’t really know anything about acting yet,” she says. “But I do want to become a good actress. Right now, I’m like an old flannel, just soaking up every bit of information I can get when I’m working. I would like to try something really dramatic one of these days and shriek and yell all over the place. But l like comedy because there isn’t so much strain.

“I’d also love to do a western,” she said. “I adore cowboys. But in my movie, I’d really like the Indians to win. I don’t mean to rewrite American history, but the Indians were in the right, you know.”

So far, she said, her mother has a clear field in the family on writing. “Except maybe for Juliet. She writes beautiful poems. I write them, too, but mine are pathetic little poems. I’d never show them to anyone. I write them down in my journal. It’s sort of like a diary,” she said, “but I don’t write in it every day. Only when I feel like it. When I see something beautiful or I have an interesting conversation, I write it down. Sometimes, when I feel like the bottom of the basket, it helps to write.

“I have ugly days,” she explained. “Juliet and I used to have them together. We’d just sit around feeling ugly and hating the way we looked. It was great. We’d go out of our way to make ourselves i look even uglier. Like I’d tell Juliet, ‘Take off that sweater, it’s too pretty,’ and I’d throw an old, torn one at her to wear instead. Eventually, the feeling would go away. Especially when we had an ugly day together. Juliet could never look ugly enough.”

As we talked, I thought of something one of her countrymen, George Bernard Shaw, had once said about youth being wasted on the young. Of course, he’d never met Hayley—even on an ugly day. Nothing is wasted on her.

Perhaps that’s her secret. Hayley’s young and has no complaints about it. She just acts her age. She did it at five; she does it at fifteen. What she knows that so many people don’t learn till it’s too late is that you get only one chance to live every year. She has fun at fifteen, because she knows she’ll never be fifteen again. She knows that if you live too much in the future, you lose too much today.

As for Hayley’s future, there’s only one cloud on the horizon. Next year, she’s going to a finishing school in Switzerland. That’s where they make a proper lady out of you.

It shouldn’t happen to someone as alive as Hayley Mills.

—FLORA RAND

See Hayley in “The Castaways,” Buena Vista, “The Chalk Garden,” Universal-International, and “Whistle Down the Wind,” released through Pathe-America.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1962