For The First Time! The True Life Story Of Marilyn Monroe

Probably at no time in the history of movies have so many men been in love with one woman. Soldiers, sailors, Marines, Hollywood executives, not to speak of baseball players! And, while Marilyn Monroe is still single (if she still is at this reading), any one of them may by some miraculous chance become her future husband.

But no matter what man marries Marilyn, he will be haunted by the first and perhaps greatest love of her life. It may be at the hour just before dawn as Marilyn stirs restlessly in her sleep, her thoughts completely ruled by her subconscious. Suddenly she may sit bolt upright in bed, and her husband, abruptly wakened from deep sleep, will ask, “Sweetheart—what’s the trouble?”

“Nothing. Nothing.” She may murmur. “Just a little nightmare.

And Marilyn herself, in the morning will hardly remember the incident, or the fact that she was really aroused by the alarming wail of a distant police prowl car. She would deny, even to herself, that in half wakefulness a split-second question passed in her mind: “I wonder if that’s Jim?”

Jim, the dark-haired handsome football star, the boy she loved and the man who, rightly or wrongly, rejected her love by persistently thwarting her ambitions. Jim, the ex-husband, and police rookie who came to her side when she needed him, after their divorce, but who still could not be moved by the tears of the loveliest, sexiest girl in Hollywood.

Amazing? Yes, when we think of Marilyn Monroe as the most sought after girl in Hollywood. But no—no, the situation is not so startling when we remember that for all of us the first big love in our lives is the one we always keep for a secret place in our hearts.

I know whereof I speak, for the Jim in Marilyn Monroe’s life is my brother, and as Marilyn Monroe’s ex-sister-in-law, I have decided that the time has come to tell the real truth about the girl for whom I once wept, cheered, frequently despaired of as a member of the family. And whom I still love as though divorce and fame had not again made us the strangers we were before our first meeting.

My mother was living on a small ranch in the San Fernando Valley, and just behind the house my folks lived in was a small house occupied by a most charming woman by the name of Grace Goddard. As they chatted over the back fence, Grace frequently mentioned her lovely coster daughter who was living. with her “Aunt Anna” in Santa Monica.

“She sounds like exactly the sort of girl Jim would like,” Mother told me, the day I first met the girl who is known today as Marilyn Monroe. Not quite 15, she was the most beautiful little creature I had ever been. Not only did she have beauty, but everything else it takes to make a lady. I loved her from the beginning. I told Mother, “You know how Jim is, so stubborn, sometimes. She’s just the girl for him, but if he thinks we want them to start going together nothing will happen.”

So we contrived for the two of them to meet, and I was right.

Honest and forthright, Marilyn. (I’ll call her that, but her name was Norma then) told Jim right off how old she was. He liked her, but he thought she was much too young to date. Mother and I made no comment, and just like a man Jim fell and tell hard on their second meeting. At the time, I lived in Ventura County. It was only a short distance to beautiful Lake Sherwood, and on Sundays Jim always wrought Marilyn to spend the day. They event fishing, rowing, or just went hiking.

My brother Jim always needed a little explaining. He was as handsome as they some, but he was always the gentleman, and never the wise guy. His father used to say, “Jim ain’t got no smart,” but he didn’t mean it unkindly. He meant that him was unmercifully honest and old-fashioned. We were all proud of him for it.

As for Marilyn, little by little on these Sundays I came to know her and the facts about her early life. They were not pleasant. No wonder that to the present day. She has wanted to keep them secret. She a learning, but cannot seem to realize, that the best thing to do is to cheerfully admit your background. Then no one will big it up as a big “scoop” later on. Betty Hutton felt the same way Marilyn did for awhile. Then, after a writer revealed the fact that she used to sing for pennies and nickels outside saloons in Detroit when she was little, Betty became proud of her tough beginnings, as well she should.

Marilyn talked to me many times about her childhood. It is quite true that she was “kicked around” a lot, and “farmed out” to various families, because her mother was taken ill and couldn’t care for her. But there is a significant fact about this situation. Marilyn was such a wonderful child that she completely captivated the two most outstanding families she lived with. They were comparatively poor people with children of their own, but they loved and cared for Marilyn in a way that couldn’t have been bettered by any millionaire whose name you’d find in the social register.

There was one very religious family (Marilyn herself turned to Christian Science) that loved her dearly, but had to give her up because they just couldn’t afford another mouth to feed. Still, the mother of the family was invited to her wedding at Marilyn’s insistence. A docile and subdued little person, her pride and devotion cast a glow of warmth over the whole event.

Then there was another family. They were maladjusted to life. They drank a good deal, and Marilyn prayed for them. She was only about seven years old at the time, and told me that her only dolls were empty whiskey bottles. “Day after day,” she said, “I’d dress the ‘dead soldiers’ in little wisps of cloth and call them ‘my babies.’ And when I grew up, I could understand one thing a lot of parents They’d give beautiful dolls to their children who in turn would ignore them and play with little beaten up characters made of rubber with the painted eyes gone. To me, those whiskey bottles were real dolls, and I think that most parents should pay more attention to what’s in a child’s mind than they do to the pretty things they can buy to influence that mind.”

I Am certain that people laugh, today, when they read what some reporter has to say about Marilyn’s intelligence. I don’t. She learned about life and psychology in the school that has produced not only our greatest actors, but our statesmen and educators as well. That was a hard school, and let’s face it, the forbidden question of sex comes to girls at a much earlier age than most parents will admit. Girls who come from the wealthiest and finest of families suffer from want of understanding in this respect. Marilyn didn’t. Her mother, born under an ill-fated star, was unable to give Marilyn the constant companionship she needed, but she did give her a great love, and it was returned by her daughter. Unfortunately, her mother’s illness prevented her from giving Marilyn all the attention she needed at this age, but other women gave Marilyn her attitude and intelligence toward the opposite sex with the result that she was a thoroughly “good girl.”

That’s why, today, you’ll find hardboiled reporters speaking with such utter amazement about Marilyn’s fine qualities. She may look like the greatest movie siren since Jean Harlow, but, like Jean, this is all window dressing. I’ve never known a man who really got to know Marilyn who didn’t look at her with as much respect as they would accord to their own sisters.

I am not an expert writer. If I were, I might try to break your heart with the account of the occasions on which, driving with Marilyn through Hollywood to our place in the country, she’d point out a beautiful white house high in the hills. “I lived there once,” she’d say, “before mother was ill. It was beautiful. The most wonderful furniture you can imagine. A baby grand piano, and a room of my own. It all seems like a dream.”

No wonder her memory clung to those days, for despite the kindness of the people with whom she lived, Marilyn’s beauty could readily have turned her into a tough, cynical teen-ager. For instance, at one time there was a young smart alec about 16 years of age who habitually hung around a certain corner which she had to pass on her way home from school. He took great delight in making obviously obscene remarks. When she could stand it no longer, Marilyn told an older companion what was happening. The next time she crossed this street, her friend followed a few yards behind her. The boy began to annoy Marilyn, and in an instant her friend grabbed him, slapped him soundly and called for the police. A store-keeper came out and testified to the fact that the boy was lying in his claims of innocence. The fellow was let go with a stern warning.

In spite of the problems of moving from family to family and school to school, she was a good student, a gracious and decent girl. My mother and I sensed this, in the way that women will, which is why we were proud when she began to go with Jim. And believe me, if she hadn’t been a fine girl, we’d have done everything we could to break up the romance, because Jim—

Well, let me tell you about him. From the time Jim Dougherty, bless his fiery Irish heart, was a small boy, he loved music and could fight his way through a whole school of tough kids. At Van Nuys elementary school he took up the violin and played in the orchestra. When he was 12 he joined two Mexican boys—twin brothers—in a hill-billy band. On Saturdays, they paraded thru town on a load of hay drawn by two donkeys, sawing out music and picking up two dollars apiece from their sponsors, the Wray Brothers Ford Company.

Later, at high school, Jim played smashing right tackle on the football team. He was the student body president and had the lead in every school play. One of his friends during school days was a young gas station attendant named Bob Mitchum. And among his leading ladies was the sultry Jane Russell, who received almost no attention at all because audiences were so enthusiastic about Jim’s performances. Everything came naturally to Jim. He was a born leader. His music teacher, and Mr. Ingram the drafting teacher, did everything they could to get Jim to go to Santa Barbara college: and become a teacher, and everyone predicted a brilliant career for the boy.

But not a bit of this adulation went to Jim’s head. He liked to do things the hard way. In the summer he earned his own clothes by cleaning stables at a riding academy, mowing lawns and lighting the red lanterns over street repairs. He worked in the mortuary in Van Nuys. All he lacked was the ambition to stand in the spotlight.

When he proposed to Marilyn, none of us knew about it until they returned with the ring. Jim was 21 at the time, and Marilyn not quite 16.

“Do you know what?” he said to me in amazement. “She wouldn’t take the engagement ring I’d picked out. She said it was much too expensive, so we picked out a smaller set.” I’ve never seen a happier girl after the engagement announcement.

In the crowded memories one big day was the Sunday on which we had our annual family picnic at Lake Sherwood. Among those present was our family minister, the Reverend B. H. Lingenfelter of the Christian Church of Torrance, California. When he was asked to officiate at the marriage on June 19th, he delightedly explained that this was the same date as his own marriage many years before.

Most of the afternoon, during lulls in the hilarity, Jim strummed the guitar and sang “I Love You Truly” and “Always” to Marilyn, who was unusually pensive that day. Her only contribution to the fun was a quiet smile of pride—and six lemon pies. (They were dreams, and I never did get the recipe, which she learned from her mother.)

I recall that. it was Aunt Anna (with whom Marilyn lived for some time) who had the wedding dress made. It was a lovely thing of eyelet embroidered organdy, and while a group of us were looking at it, someone brought up the question of who would give the reception after the wedding. Marilyn spoke up promptly and said, “The bride’s parents are supposed to take care of that!”

“I know dear,” one of the catty feminine neighbors said, “but you have no parents.” I’ll never forget the look of sadness Marilyn gave me. And I Still detest the thought of that offending woman.

To this day I can close my eyes and see the wedding as though. it were a part of last night’s movie. Marilyn was the most gorgeous bride I’ve ever seen. The wedding was held in a lovely home of family friends on Bronson Avenue in Westwood. Their twin daughters were the ribbon-stretchers and my son, Westy, age eight, was the ring bearer, proudly carrying the wedding rings on a satin pillow. (Today he is at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, awaiting embarkation for overseas duty.)

Everyone seemed to be weeping as the “I do’s” were said, except the bride and groom. As they kissed, Mrs. Anderson, who had kept Marilyn for awhile, exclaimed, “That’s my baby! That’s my baby!” I know that Marilyn was saddened because her own mother couldn’t be present, but on that happy day she had a half-dozen mothers!

Then, after the moment of ecstasy, the fun started. My older brother, Marion, who never could resist a practical joke said that it would be a shame to deprive the public of a chance to see such a beautiful creature. (He didn’t know how prophetic his words were.) And as a result, after the wedding pictures were taken, Marilyn was kidnapped!

Marilyn appeared at the proper moment and we all waited for her to throw the bridal bouquet. She raised her arm and exclaimed, “To heck with that! I’m taking these flowers home to press and keep.” A moment later, she disappeared. Jim searched for her and was finally told that she was out in front in a car, ready to go to the Florentine Gardens, a night spot on Hollywood Boulevard about a mile below Vine Street. It took a lot of persuasion for Jim to go along, but he finally did, and when they entered the place, the band struck up “Here Comes The Bride.” During the drinking of toasts to the bride, a Conga line was started, and Marilyn joined it, still wearing her veil. She seemed to be having the time of her life but I did see her look anxiously toward Jim every now and then, who appeared to be sulking at the sidelines. I knew he was only trying to be patient while his friends had their fun, and it didn’t occur to me that this scene was an actual preview of what was to happen to their love some years later.

You may have read in some column or other a casual reference to Marilyn Monroe’s marriage to a young aircraft worker—a marriage of short duration. Don’t you believe it! Those two kids were married for four years. They were so madly in love that it hurt to watch them. The reasons for their divorce were pathetic, almost stupid, but at no time during their marriage was Marilyn other than a dutiful, adoring wife and a perfect housekeeper.

I’m a little ahead of the story, but I had to say that, because I love my brother Jim, and I loved Marilyn as I would my own sister.

There was no time for a honeymoon, because Jim had just started work at the Lockheed Aircraft factory. So they moved into a little house they rented on Bessemer Street in Van Nuys, and Marilyn plunged into the role of housewife with great eagerness. At last she had her own home. She tried out recipes by the dozen on all of us. If ever there was a girl in love with her man, Marilyn showed it in every way.

She packed Jim’s lunch every day and on, the 19th of each month, their anniversary, she always enclosed some little token or memento—a note, or a small gift.

During the first year, Marilyn came to my home many times, to play with my son, Larry. “My first baby has to be a boy,” she told me, “a second Larry.” And she was wonderfully kind and patient with me while I was carrying my little Denny. At the time I was staying with my mother in Van Nuys, so Marilyn stayed with me during the day, and Jim picked her up at night.

One day Marilyn asked, “Elyda, do you have to go through all this when you have a baby?”

I replied, “Yes, honey, you have to. If you want your own child you must bear it.”

Without hesitation she declared, “Well then, if you do, you do. I certainly want to be the mother I was intended to be!”

On the evening of October 6, 1942, at six p.m., Marilyn left and made me promise to call her if anything happened. Denny was born the next morning at three, and when Jim and Marilyn arrived at seven, my new sister-in-law had a wee, pink and sprawling mite of humanity on her hands. She’d never handled a baby before, but her confusion soon changed. She took over exactly as though she’d been a trained nurse.

For almost a year, young Mrs, Dougherty was the happiest bride alive. Then, abruptly, Jim came home one night with the news that his draft status had changed and he had enlisted in the Maritime Service. They were separated briefly when he went to boot camp, but within a month he was back home with the news that he would be stationed at Catalina Island as an athletic instructor, and that, being a married man, a furnished apartment went with the job.

Now they were deliriously happy, for they could have their honeymoon, and Uncle Sam would pay for it!

While Jim was sweating it out with the new recruits, Marilyn did the shopping and cooking. In the evening, they danced with friends to the tunes from a new record player. And Marilyn, daytimes, seldom ventured on the beach. It was a re-occurrence of the trouble she’d had since early in her teens. She was just too beautiful. As one friend put it, “She can’t help it that men’s wives look at her and get so jealous they want to throw rocks!”

All this time Marilyn’s constant companion was Muggsy, a mutt collie dog. She spent hours bathing him, grooming him, teaching him tricks. For those four delightful months they were inseparable when Jim was not home. (I mention this because old Muggsy played an important part in what happened later in their lives—and almost saved their marriage.)

Then came the day that Jim had to ship out. That weekend, Marilyn came to visit me. She’d no sooner stepped out of her car than a man, passing slowly in a convertible whistled at her and yelled, “Some shape!” Marilyn turned and yelled at him, “Move on, old man—go pick on somebody nearer your own age.” And as she came up the walk, her eyes were filled with fury. That night we had a family conference and Marilyn tearfully urged mother, who was then working as company nurse at Radio Plane, makers of target planes for Air Corps gunnery practice, to help her get a job. Like many other young wives, she couldn’t bear the thought of the endless lonely hours of inactivity. She couldn’t find words of her own to explain to Jim, so in one of the first of her daily letters to him she simply copied the words of the song, “I Walk Alone.” . . .

And Marilyn meant every word of it. More than one man at Radio Plane wanted to date her. Even in cover-alls she was lusciously feminine. But before long the word got around that Marilyn was walking alone—for keeps—until her man got home. All she thought of was working and making money to save for Jim and their future together.

I remember Mom bawling her out for working in the paint shop. “Honey,” she said, “you’ll ruin your beautiful hair—and all those fumes—it’s just not good for your health.”

But Marilyn persisted, even though she came home looking a wreck, until Mom finally settled the matter by going quietly to an official of the company, who arranged a transfer.

Marilyn never hinted that she knew what had happened, but the first thing we knew, she announced that she’d taken a modeling job. I asked her whether she’d told Jim about this. She replied simply, “Of course. I tell Jim everything.”

About this time Radio Plane was planning the first company picnic, and the girl who sold the most tickets was to be crowned queen of the event. Marilyn was too preoccupied to enter into the event, but the men in her department took over, and she was elected hands down.

I’ll never forget the day. When the ceremony of crowning the queen was over, Marilyn was so thrilled and touched at what her co-workers had done for her that she broke down and cried. Then, recovering her composure, she relaxed her almost chilly attitude toward the men with whom she’d been working and danced with every one of them.

“Gosh,” a fellow named Bill exclaimed to me, after he’d been cut out, “what a girl!”

“I know,” I replied. “Isn’t it too bad she’s married?”

“Yeah,” he grinned ruefully. “All she talks about is ‘wait until Jim gets home!’ ”

And when Jim did come home, Marilyn promptly introduced him to the whole gang at the next company dance. She made the complete rounds. “Joe, this is my husband, Jimmie.” Then she’d stand there, completely lost in silent adoration of her man. After awhile, this routine began to embarrass Jim. He said to her, “Honey, after you introduce me, for Pete’s sake start a conversation or something. Just don’t stand there looking at me with those big eyes. People just don’t understand!”

In those highly emotional days many hearts were broken. Service men came home to find their wives and sweethearts no longer belonged to them. When I read somewhere, a few months ago, that Marilyn had sent Jim a “Dear John” letter while he was overseas, I was furious. Marilyn never wrote such a letter, then.

Today, Jim has remarried. He has a lovely wife, three children, and is completely happy again, but his marriage to Marilyn did not crack up through jealousy and lack of faith to each other during war time.

Naturally, Marilyn was aware that other wives and sweethearts dated while their men were away, but she never did. Furthermore, she never gossiped about these situations, nor would she listen to gossip. Her whole life was wrapped up in her love for her husband.

The trouble that was brewing between them was a long way from the surface. When Jim came home, they had their own secret places to go together. Marilyn was lost to all her friends until Jim shipped out again. They were so completely happy that they didn’t need anybody else.

The rest of the world, however, was beginning to need Marilyn. From the publicity that came from her being crowned Radio Plane Queen, more and more modeling jobs were forthcoming. Most of the time she could do these while Jim was away, but on one occasion Marilyn had some pictures to do at a turkey ranch. Jim went along and busied himself elsewhere while she was working. On the way home he kidded her about feeling like being married to a movie star.

Marilyn was very subdued when they came back to the house and went immediately to her room and closed the door. None of us thought anything about it at the time, until my son, Westy, rushed downstairs exclaiming, “Uncle Jim—Uncle Jim—Auntie is upstairs crying!”

Jim took the stairs two at a time. en he finally managed to calm Marilyn down he found out the reason for her hysteria. She had lost her engagement ring at the ranch and was completely heartbroken. This, and Jim’s kidding had been too much.

Yet, in that quiet way she has, the tears were soon gone. Being a Christian Scientist, Marilyn firmly believed that they would find the ring. Imagine being certain you could locate such a tiny thing as a diamond in a field of several thousand turkeys. We all tried to convince her it was a lost cause, looking for the ring that might by this time be nestled in the tummy of a fat bird on the way to the butcher’s, but she was determined.

The next day they went back to the ranch. They retraced every step Marilyn could remember they had taken, and believe it or not, came home with the ring.

Every time Jim shipped out, Marilyn went through a period of desperate loneliness. She and Mother became the closest of companions, going to the beaches and the movies together as she talked of her future plans. She was satisfied enough with the $40 salary, but as she said, “I don’t want to work in the ‘dope room’ forever. (This was the room in which lacquer was applied to wings.) Jim will have to decide what he’s going to do when the war is over, and if we’re lucky, we’ll have enough saved so we can have our own home and he can take plenty of time to choose the line of work that will really make him happy.”

If memory serves. me correctly, Mother told me about this the day before Marilyn was nearly killed in an accident. “I just love that girl,” she said. “I never knew anyone more unselfish, but she is so lost in her own world that she frightens me.”

The words could have been interpreted to have been a premonition, for the next evening I had a phone call. Marilyn was laughing, but there was an edge to her voice as though she was on the verge of tears. She’d been driving home from a modeling job in the little Ford V-8 she and Jim owned at the time. “I guess I must have been dreaming again,” she said, “because I drove head-on into a street car. You should see our poor car. It’s completely demolished!”

“But what about you?” I asked anxiously. “Are you all right?”

“Sure, honey,” she replied. “All I have is a small bump on the head. I guess it’s a miracle that I’m alive.”

This was shortly before Christmas. Jim came home on leave, the war was almost over, and they were all set for a wonderful holiday. Then Marilyn had a call from the model agency—a nice-paying job up in the mountains for some pictures to be taken in the snow. Jim wanted her to cancel out so the family could all be together on Christmas Day. Marilyn pointed out that if she refused to go, she’d not only lose this job, but others. It was a part of what you had to put up with in the modeling profession. Anyway, he could come along with her.

You know how it. is with a man, sometimes. They didn’t really need the money. He felt, and not without reason, that he’d look and feel silly tracking along after her, but Marilyn couldn’t see it that way. Stubbornly, they argued, until Marilyn stormed out of the house.

That was the most miserable Christmas either of them had ever spent.

Now the rift between them began to widen. With the war over and Jim home to stay, the differences which seemed small in view of their love for each other began to grow to terrible proportions. Before any of us realized what was happening, they had separated. I like to think, sometimes, that if the war had not intervened, Jim might have gone on to become an outstanding actor, and Marilyn, his wife, could then have pursued the same profession. But then, that’s just a sentimental sister, dreaming.

From the time of Marilyn’s first movie offer, the die was cast. His ultimatum was that she had to choose him or Hollywood.

Marilyn was heartsick. “I love Jimmie so much,” she told Mom, “but I just can’t understand his attitude.”

Mother advised Marilyn to do as she thought best, and no matter what she did, she would still be loved and understood by the family, who would always stick by her.

The divorce came in the fall of 1946. Marilyn went to Las Vegas, and when she returned we saw and heard very little of her. I know why. She blamed a great deal of the trouble on herself.

Jim was temporarily living at home the night the telephone rang. It was Marilyn. She was crying so hard I couldn’t find out what the trouble was. She wanted to talk to Jim. A moment later, he rushed out of the house and I said a little prayer that this might mean reconciliation. No woman frantically calls a man she has just divorced unless she needs him, terribly.

The next day I learned that Muggsy, their ancient and lovable collie, was dead.

That moment when they faced each other in common grief over the death of their pet, the floodgates of emotion must have opened wide again to review for them their first pledge to love each other forever. But, if she cried her heart out in Jim’s arms and asked him to comeback to her, and he refused, I’ll never know.

For when Jim returned home he never mentioned what had happened and, knowing him I wouldn’t have dared to ask.

All this happened a little more than six years ago. For Jim’s part, he fe what he was looking for. He fell in love again. He found the type of work he wanted. It may be hard for Hollywood to understand the fact that he became a policeman and a darned good one. That he is happy as a public servant, and one of the best, is true. That he is a good father to the three children he loves so well, everyone knows. As his sister I can say that I am more than ordinarily proud of him.

You see, it is possible for a man and a woman to find new happiness after a first great love has failed. There is no reflection to be cast on either of these young people—Jim or Marilyn—for if any couple should penalize themselves with mental suffering for years after a marriage failure they wouldn’t be normal human beings.

Marilyn and Jim, today, are young people to be proud of, even though they walk in widely separate paths—paths which have crossed only once to my knowledge since the final separation. That was on the day Jim was assigned to a studio lot where Marilyn was playing a bit part.

During the afternoon, Marilyn passed by and was surprised to see him there. They talked cheerfully for a few moments. Then Marilyn left to go back to the set. And as she did, a worker stared at “Miss Monroe” in her abbreviated costume. Like the nasty little boy way back in the days of her childhood, the fellow made a smutty remark. He must have been the most frightened man of the hour, because he was suddenly jerked off his feed in Jim’s strong hands.

“Listen, you,” policeman Jim Dougherty growled, “watch your language!”

“Take it easy, officer,” the terrified grip gasped, “I didn’t mean anything. Besides what’s it to you?”

“Nothing,” Jim snapped. “Except you’d better learn never to make cracks like that to a lady. And that girl’s a lady—was married to her for four years, and know!”

That’s the whole story. Perhaps if you told it to a movie producer he’d say it’s too improbable to be good as a picture plot. But, no matter who she may marry—Joe DiMaggio or a man she may meet tomorrow, Marilyn Monroe has live through as great a romantic drama as she will ever star in.

As for me, her ex-sister-in-law, Elyda Nelson of Anaheim, California, a plain thing before—much less a screen play—I call the story, “Her One True Love.”

THE END

—BY ELYDA NELSON

(Marilyn Monroe can be seen in 20th Century-Fox’s Niagara.)

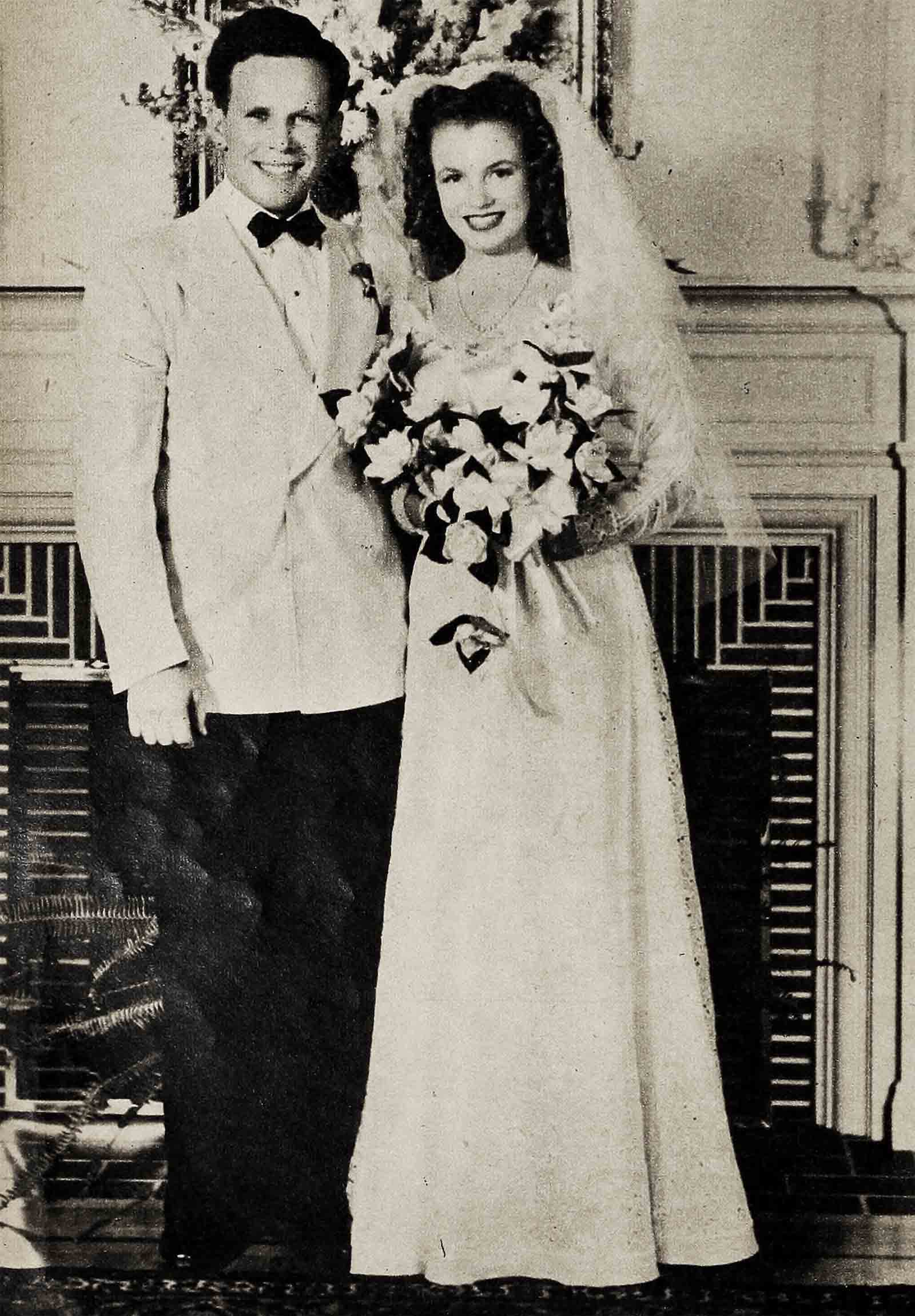

These pictures chronicle the unhappy story of Marilyn Monroe’s first romance. They come from the family scrapbook of a woman who knew her intimately, Elyda Nelson, the sister of the man Marilyn met, married and left behind long ago Jim was a simple man, content to lead the useful, but obscure life of a policeman. Marilyn wasn’t made for domesticity . . . a dazzling career was her goal. Her success is a legend, now, but does she have what she really wants, at last?

1- This is how Marilyn looked at 14, the first time her husband, Jim Dougherty, met her. He fell for her right away.

2- They married two years later; Jim was 21, Marilyn not quite 16. She wouldn’t accept the engagement ring he selected, insisted on a less expensive one. Although her mother couldn’t attend, several of her “foster mothers” were present.

3- There was no time for a wedding trip, but, a year later, Jim enlisted in the service, was sent to Catalina. They loved it there, called it a honeymoon.

4- Marilyn shared this first letter, and the ones that followed, with Jim’s mother, after her husband was shipped overseas.

5- “To the most wonderful hubby in the whole wide world, love, Norma Jeane,” was how Marilyn in scribed this picture she had taken to send to him.

6- This is the house Marilyn (left) rented when she worked at Radio Plane while Jim was away at war.

7- Co-workers chose Marilyn (second from right) Queen, The publicity brought modeling jobs.

8- Modeling for ads, magazine covers, like this one took a lot of time. Jim didn’t mind until it began interfering with his seeing her.

9- A policeman’s life appealed to Jim (left), who joined the force when he got out of service, but Marilyn longed for a career.

10- After they were divorced in 1946, Marilyn continued modeling. Fashion shots like this led to movie nibbles. Her first part was in Scudda Hoo, Scudda

11- It was a small part; but even then Colleen Townsend, director F. Hugh Herbert, knew she was on her way up.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1952

No Comments