A day To Remember—Esther Williams

Esther Williams’ mother-in-law has a penchant for saving mementoes. No matter how old, faded or worn, if they mean anything to the elder Mrs. Gage they are wrapped in ribbons and tucked away. Otherwise Esther would have got away with it the night Ben came across the battered box under the window seat.

He’d been looking high and low for some canceled checks that would untangle his income tax work sheet, and now he was pacing the livingroom dramatically, hoping for help from his wife.

“They’ve got to be somewhere,” he said. “You just don’t throw things like that away.”

Esther put her book in her lap and regarded him in her Wifely Manner. “You haven’t thrown them away, dear. If you’re your mother’s son, they’re still around here somewhere.”

And so it was that, long minutes later, when Ben unfolded his big frame from a kneeling position in front of the window seat, holding a large, falling-apart cardboard box, he was wearing a remarkably evil grin.

“Ha!” he said.

Esther looked up from her book again. “What are you snorting about, sweetie?”

“You, too, are a string saver—Mother Gage,” he charged.

“What are you talking about?”

Ben strode to the center of the room and gestured as though stroking a long beard. ‘“Heah!” he shouted. “Lindy! Were you out theah with that Lee cur? If you were ah cain’t see how you could be mah daughter!”

Esther’s first thought, naturally, was that Ben had gone mad. And then, out of the past, came a faint recognition of those lines. Back in George Washington High School, in ’38 or maybe ’39, she had portrayed a character named Colonel Brewster in a musical comedy. It had been part of a football rally and Esther had been the colonel (because (1) nobody else would, and (2) because of her height) sporting a beard and a southern colonel-type hat. The play hadn’t been exactly Noel Coward caliber. In fact, Esther had written it, and it had been pretty awful.

She came back to the present with a start, and jumped out of her chair. “Ben! Where did you get that? Give it to me!”

And Ben held the box above her head. “From whom was Essie Williams hiding in the cafe closet?” he mimicked.

Esther groaned. Her treasured Memory Book must be in there, too, with all the gossip columns from the school paper, the dance programs, the flowers. “Ben! Please!”

“I understand a guy named Randy Henderson took you bowling and didn’t have to pay for you because your score was so low.”

He finally lowered the box and gave it to her, on the condition that she answer some questions. “Who,” he said, “was this Jimmie character whose name appeared on every page? And who were Frank and Kenny, the ones who always took half the dances away from Jimmie?”

“One at a time,” said Esther. “Jimmie McKinlock was one of mother’s pets. I went with him while he was still in school, a couple of terms ahead of me. I don’t know about Frank and Kenny—it might have been Frank Cookson. If you’ll give me that box, maybe I can find out.”

“What about the poetry?” goaded Ben. He snatched a rumpled paper and read,

“Once upon a time I knew

A coy, petite young miss.

There wasn’t a thing I wouldn’t do

To earn from her a kiss.”

“Help!” howled Esther, but Ben continued.

“However, she was not the type

To lose herself in love.

She was young and frivolous

And flight as a dove.

The first time that we e’er went out

I lost my head, I did.

And so I close with these three words,

I love you—Esther kid.”

By that time Esther had collapsed in hysterics and Ben wasn’t much better off.

“I know you’re enchanting and all that,” said Ben, “but tell me how you managed to collect a whole box full of poetry, all from different guys?”

“You might say I asked for it—in selfdefense.”

Ben grinned and lit his pipe. “Elucidate.”

And so she told him how she used to wonder how to say no when a boy wanted to kiss her—the classic problem of the teen-ager. She had gone to her mother for advice and her mother had said “Talk about something else. Get their minds off the subject.” Even the sixteen year-old Esther knew that bit of advice wouldn’t work for thirty seconds. And said so. “All right,” her mother had said. “You’re smart. You think of something to say.” So Esther cooked up a line: of defense. The minute a boy began his overture she backed off and looked at him coldly. “Why do you want to kiss me?” inquired the young Miss Williams. This usually set him back two or three years and when he recovered Esther said charitably there was no hurry for his answer, that he might like to give it to her in the form of a poem. So she collected a ream of poetry (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) and the system, as a stall for time, worked.

Remembering all this, Esther slipped into a comfortable hour of reverie, poring over her souvenirs, sharing some of her memories with Ben, punctuating others only by a giggle. Husband-like, Ben wanted to know, what with all these slaves at her feet, hadn’t Esther ever had a crush on any of them. Had she? There had been devoted Jimmie, but before he joined the Coast Guard she had been too young to be serious. And Don Schutz, the boy famous for being the only one with a car of his own, and Frank Cookson captain of the football team. She and Frank had double dated so much with Bud Fisher and Barbara McConnell. Whatever had happened to them all? And there was Randall Henderson, dear, sensitive, deeply intelligent Randy, who later had been killed in the war. There were dates with all of them and a certain fondness for each, but she couldn’t remember a crush until she thought of Frank Reynolds. He had been the football hero and she recalled that after he made that ninety-yard touchdown she kept dreaming of it—and of him. There was the night she went to her first formal dance, wearing the peach chiffon handed down from her sister’s wardrobe. She had walked into the gym on Jimmie’s arm and there had stood Frank Reynolds. Esther believed this was a rare creature, a blond giant, and when she heard him tell Kenny There’s a nice looking dish—I’ll have a dance with her, Miss Williams stood riveted to the floor. Kenny had warned her about Frank, reputed to be the school’s sophisticate, and tried to keep them apart. ‘You’re too innocent for him,’ Kenny had said like a big brother.

She remembered the football rally immortalized by the stunt she had dreamed up, in which she and four other girls swiped the team’s jerseys for their song and dance number. It would have gone great, except that when the girls managed to get the jerseys out of the boys’ lockers they considered one and all sufficiently gamey to deserve a tubbing. So they took them to Esther’s house and dumped them into the washing machine. When they came out the red numbers had run into the white jerseys until the whole thing was a pink mess, with the numbers indistinguishable.

She spoke aloud to Ben. “Poverty Flats, we used to call it. Because the kids who went there came from such poor families. But Ill bet there was more fun there than at any other school in L.A.”

“You were busy enough,” said Ben, looking up from her year book. “From what I can find out by a casual study you were in the Tri-Y two semesters, a member of the Scholarship Society, and an officer—usually president—of your class, of the cabinet, of the Girls’ League, whatever that is, of the Student Body, and of the Commerce Honor Society.”

“I was so busy,” Esther laughed, “I had to go to City College for my education.”

“Some fireball,” said Ben. “Here’s one of your speeches, for some office or other. Listen: ‘You and I know that what I say here will make very little difference in the way you vote. You want in your girl’s vice president someone who will be your friend. If I have been friendly, perhaps you will trust me again to be your friend as girls’ vice president of the Student Body’.”

Esther grimaced. “Pretty corny, huh?” And Ben nodded.

She thought a moment and said, “I wonder if Spearsy’s still there.”

“Who?” said Ben.

“Miss Spear. She was my pet teacher—science. A wonderful woman. She used to be so interested in all the school activities, and she’d help us get out of scrapes all the time. She was my mentor.”

“Why don’t you call her up?”

It was as simple as that. Esther called Miss Spear, who was delighted and asked Esther to come to Washington High for lunch with the faculty. Esther asked if she could say hello to the kids while she was there, and Miss Spear said she’d arrange it—maybe an auditorium call.

The night before the appointed day, four-year-old Benjy began to run a fever. It began at 101 and climbed steadily. It was 104 by the time the doctor arrived, and he suspected German measles. “There,” thought Esther, “goes Washington High, Spearsy and the whole day.”

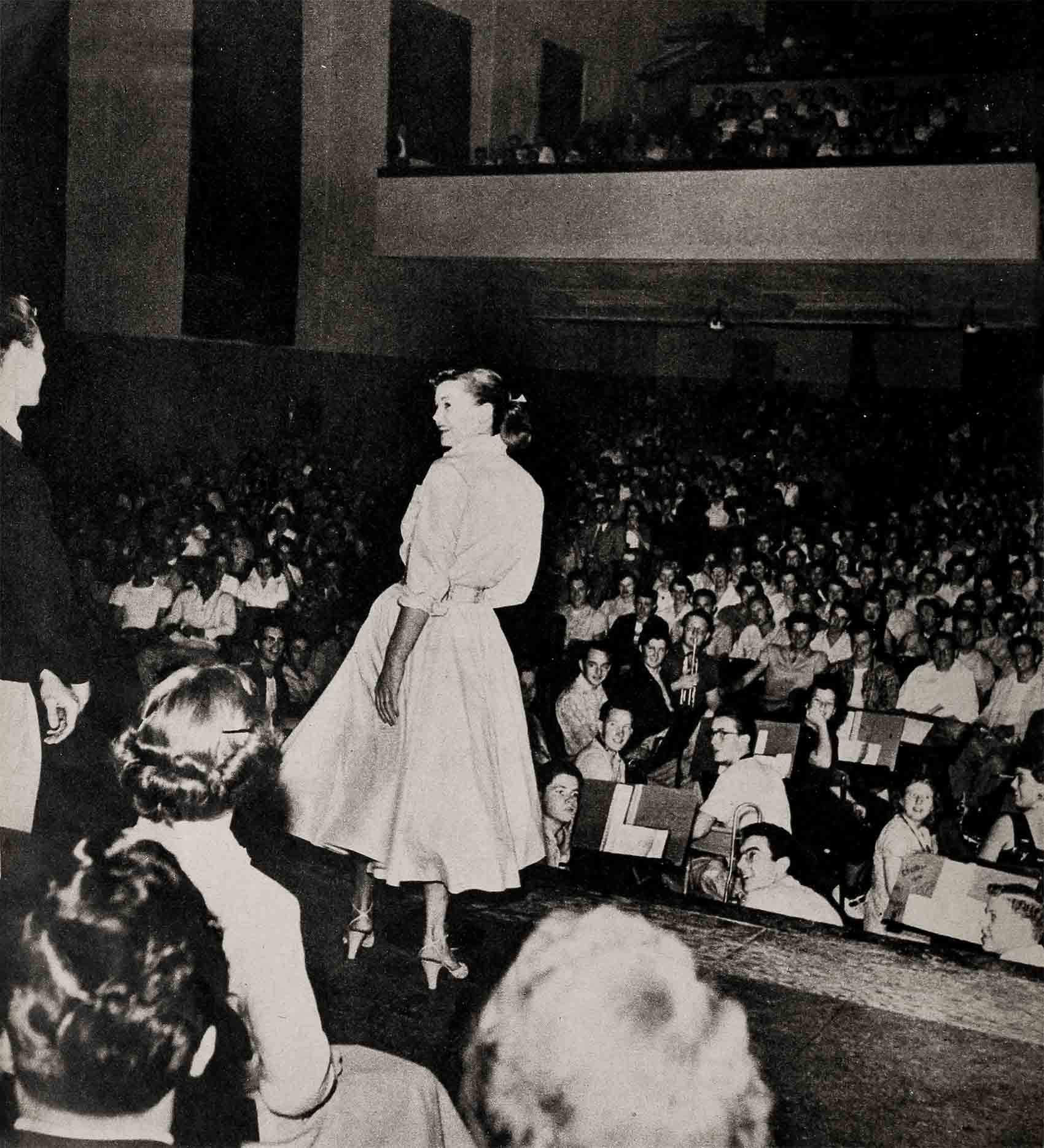

Instead of measles, however, Benjy developed a twenty-four-hour virus and through the night Esther sponged him with alcohol to bring down the fever. At five am. he went into a fitful sleep and and the next morning Esther was ready to call the school and cancel her date. But the doctor returned and said it was perfectly all right for Esther to leave for the day, the nurse would stay with Benjy. Esther flew into a pink orlon dress, jumped into her station wagon and drove the twenty miles to the school, through the city’s worst traffic, with as much speed as the law would allow.

When she arrived the first auditorium call was over, and the second ‘aud call’ in progress. Doctor Fisher, Washington’s principal, met her at the stage door of the auditorium and steered her backstage, where she was greeted by the teachers who remembered her. There was Spearsy, of course, and the two women fell into each other’s arms. And there was Miss Fitzpatrick, who’d had Esther in ‘home room, and Mrs. Segal who’d taught her physical education. There was much hilarity and Esther was puzzled at the fact that all the teachers, after fifteen years, looked exactly the same as she remembered them. “I’m the one,” grinned Mrs. Segal, “who advised you against a swimming career because it would be too strenuous for you.”

“I’ve managed to last,” said Esther. “Maybe because you put me into good shape for it.”

“I see you’re wearing glasses,” said Miss Spear. And they laughed together, remembering how they had discussed the problem of Esther’s nearsightedness and how she had worried about snubbing people. Spearsy had told her to smile at everybody she saw.

“Anyway,” said Miss Spear. “I’m happy you’re wearing them because it might have some influence on the girls here. They’re as bad as you were—afraid it’ll spoil their looks.”

While they were speaking a girl’s voice drifted backstage, a youthful voice thanking the students for bestowing an office upon her. And Esther thought of the many times. she had stood on that very stage, asking to be elected or grateful that she had been. Now a tall boy was introduced to her, Merle Lauderdale, president of the current Student Body. He went on stage to announce Esther to the students.

She joined him, almost buckling with nostalgia, and put on her glasses to hide the mist in her eyes. “I’m not wearing these to look intellectual,” she told the assembled kids. “I’m nearsighted, and without them I can get into a lot of trouble.” She told them Spearsy’s advice to smile at everybody. She thanked Merle for his introduction and remarked upon his height. “When I was here, all the boys were so short,” she said and fondly stroked the sleeve of Merle, who blushed and hurried to his seat.

Esther told them a lot of things that made them laugh. She told them of the day she was honored by membership as a ‘Lady’ in the Knights and Ladies organization, and given the prized sweater with its emblem. Esther was wearing a blouse that day which had been worn to the last straw by her two older sisters. The back of one of its sleeves had been steadily ripping all day and was now left in plain sight by the sleeveless Ladies’ sweater. Her only recourse had been to wear her long-sleeved Tri-Y sweater over everything, and the temperature that day had been just over 100 degrees—so Esther had been dissolved by both the honor and the heat.

She turned serious, too, and told them that the old cliché about high school being the best years of their lives was true. She said she remembered her first ‘dance, and the basketball games in which she played more clearly than her first screen test or her first movie. And she told them that while she might kid about studying, and grades, it was true that she had been a Sealbearer and that if they didn’t mind her giving a bit of advice, nothing is worth doing (or any fun) unless you do it well.

The teachers backstage smiled happily at the sage counsel being handed out by G. Washington’s celebrity, and afterward steered her through the school. It all looked dear and familiar to Esther, and every few minutes another teacher would approach her, and Esther would remember another friendly face out of her past. They took her to the vice-principal’s office where she signed the guest book, then to the bungalow where the Student Body holds meetings and where Esther herself had so often presided.

By the time she sat down to lunch in the faculty diningroom, all of Washington High, including those students who had missed her because they were in the first ‘aud call,’ knew that Esther was there. She found time to write this last group a note of apology, to be put on the bulletin board, before she was whisked away to the drama class. Here the Thespian Club stood her on the stage and she worried that they might ask her to spout Shakespeare, which, Esther explained, is not her forte. She stood a moment longer while a breathless boy with a complicated camera knelt to take her picture. “Gee!” he said. “I thought I’d never catch up with you. They told me there was a celebrity in ‘aud call,’ but I thought it was the County Supervisor or something, so I didn’t go. Gee, I darned near missed you!”

When Esther left the drama class and headed for a gym class on the field, the students could no longer be controlled. Wherever she passed, boys and girls broke out of classrooms, even jumped out of windows, in order to join the mob following her. Doctor Fisher, the principal, was worried for Esther’s safety, but she smiled and assured him she was accustomed. to such things.

It added up to a great day for Esther and, despite the crowds, even included a long talk with Miss Spear. It was after four in the afternoon when Esther got home, to find Benjy much improved, and soon big Ben came in the front door.

“How’d it go?” he wanted to know.

“Just wonderful, thanks to you.”

“To me?”

“If you hadn’t found that box of souvenirs, I never would have got started on the whole project.”

“Glad to be of service,” said Ben. “But I never did find those canceled checks I was looking for. Maybe if you could bring yourself to graduate from high school now and marry me—you could help me look for them!”

“Sure,” said Esther, pulling a cluttered drawer out of a table. “Like I told the kids today, school days are the carefree days.”

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

(Esther Williams’ next picture will be MGM’s Jupiter’s Darling.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1954

No Comments