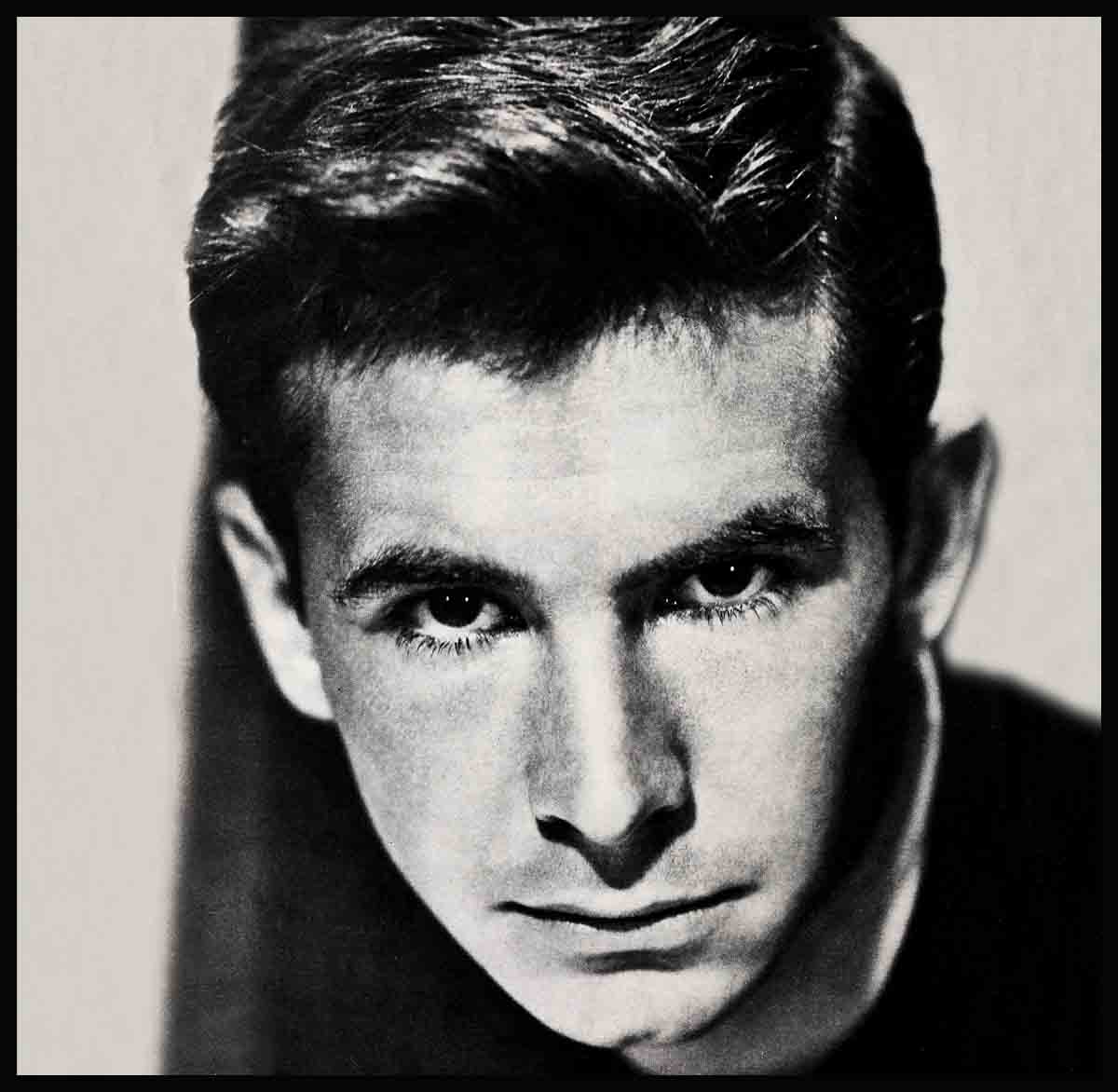

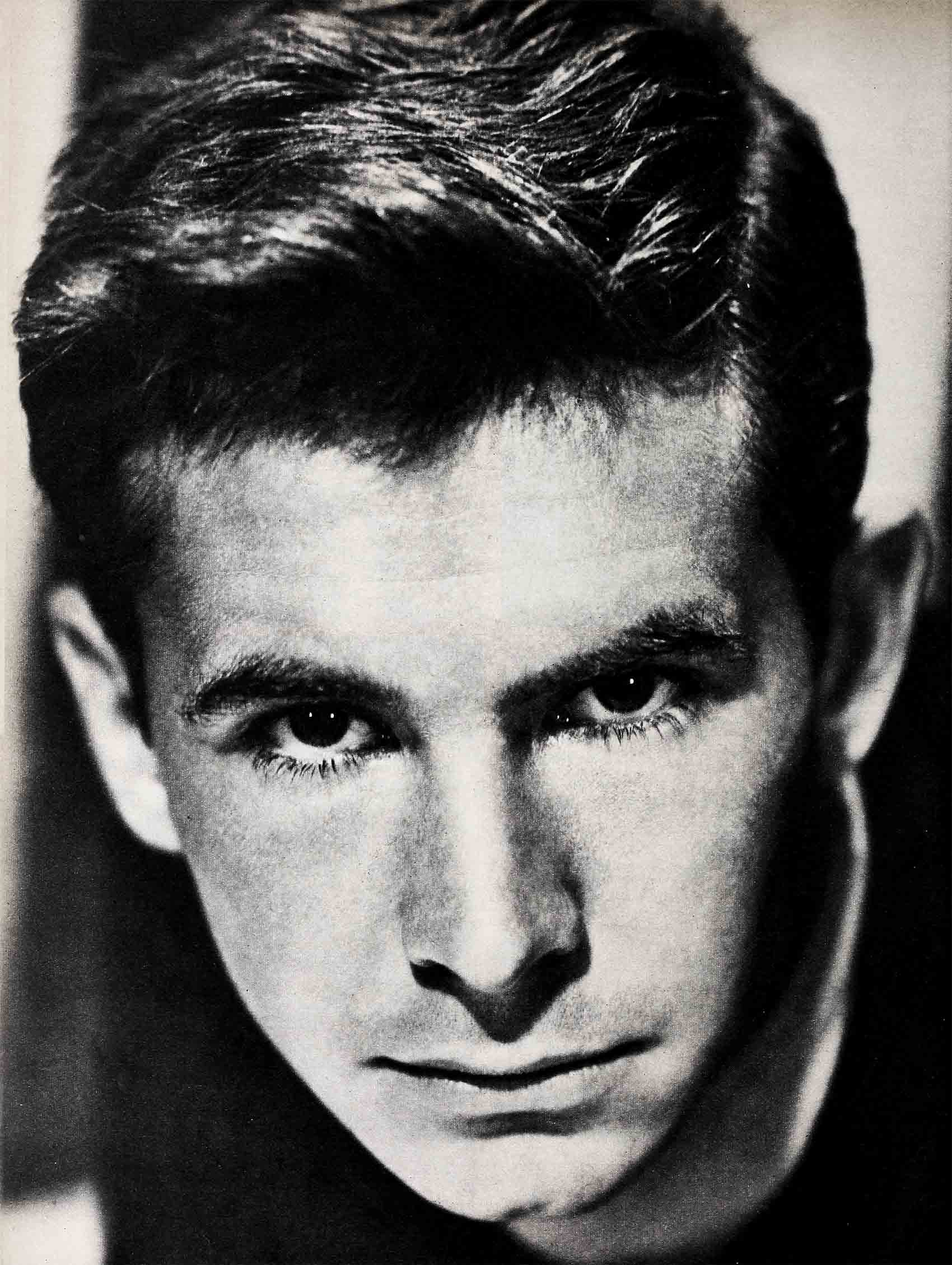

“He Still Baffles Me”—Tony Perkins

Editor’s Note: Tony Perkins was not like most children. He was what the psychologists call an “unusual” child—unusually sensitive, unusually imaginative, unusually gifted. In this first story by his mother, Mrs. Osgood Perkins, as told to Patty De Roulf, she reveals, as only the person closest to him can, the brilliant, complex boy who became the brilliant, complex actor.

My son said to me recently, “Mom, it’s going fast. Almost too fast. One picture after another. Busy every minute.” He looked at me searchingly. “I know where it is I want to go. I know what it is I want to be. But right now . . .” He stopped and glanced away, uneasy.

Tony has grown tall, in some ways wise and in many ways mature. Yet I remembered then the fifteen-year-old, the five-year-old, and I felt toward him the same way I did in those days: proud delighted, slightly baffled.

Even those closest to Tony seldom know how he really feels about things. His emotions remain hidden, and you can only guess by what he doesn’t quite say whether he has been disappointed or hurt. He was five when his father, Osgood Perkins, died. This must have been the greatest shock he’d ever experienced, but there were no tears. Leaving the memorial service at the Little Church Around the Corner, in New York, Tony remained completely composed. When an aunt consolingly caught his hand, he shook off her grasp, held his head high and walked out.

Afterwards, Tony and I took the train to Florida in an attempt to forget our loss. That first night, as we started for the dining car, my little boy affectionately clutched my arm and said, “We’re going to be all right, aren’t we, Mother?” His concern was for me, not for himself. But a while later I had some insight into his real emotions. Tony liked to make pictures, with crayons or watercolors. As he sat painting one evening, he looked up at me and said, with almost imperceptible sadness, “Isn’t it nice that Daddy taught me how to paint before he had to go away?”

From babyhood, Tony had been very much the individual, and Osgood and I felt ourselves fortunate, even in the qualities about Tony that sometimes confused us. His intelligence and his imagination reached out in so many directions. At three and a half, Tony began going to a private nursery school, where he took a piano lesson every day and learned to chatter in French like a true Parisian. In the afternoons, he’d come home and get out his paints. When he got bored with art, he’d ask to be read to. Half an hour later, he might decide to paste pictures in a scrapbook or just go outside and play—sometimes alone, sometimes with his friends.

As he grew, the restlessness remained, the sudden impatience with the project of the moment. Even today, when he isn’t working, Tony will stroll aimlessly for hours, then rush home and listen to records, then swim or play on the xylophone or his guitar, then go to a movie or wander through a museum or just stay home and read.

I sometimes wonder how my son concentrates on a script and learns all of his lines. Then I think back—and I know the answer. Whenever Tony has become truly interested in something, he has followed it through all the way. But it must be his own interest, of his own choice—or there must be a good reason for applying himself. When he was in high school, he expressed his resentment of formality by refusing to study those subjects he considered useless for his purposes: science and mathematics. His teachers finally told him that failures in these examinations would mean failure to graduate. Because he knew that I would be disappointed in him, he studied ferociously with me all summer. When the tests came, he passed.

His feelings for me were more important than his distaste for algebra. That’s where the real test of a person comes, and that’s where Tony always passes. He will do anything if it means sparing the feelings of someone he really cares for.

Nevertheless, those summer studies were merely a chore. He didn’t concentrate on them with one-tenth the intensity he devoted to subjects he loved outside school: music, art, literature. When he went to college in Florida, his record in the fields e liked was excellent. One year, he walked off with all four twenty-five dollar prizes for the best stories in the quarterly literary magazine. And in his second and third years, he won scholarships as a history major. The scholarships meant a great deal to Tony, with his already well-developed sense of responsibility. He had helped to pay his own way through his freshman year.

His scattered interests may make him sound like an impractical person, but he never has been. As a youngster, he used to remark, “I like the sound of money jingling in my pocket.” Somehow, he always made money, by one ingenious means or another. He was always a great trader. In high school, he’d trade a thermos bottle for a tennis racket, sell the racket and make enough profit to buy two more thermos bottles. During the same period, he also ran a record shop, buying records cheap from schoolmates, selling them at a gain. He used to baby-sit for friends, and when he’d meet people walking their dogs on the street, he offered his services. At one time, Tony Perkins was one of the busiest dog-walkers in Manhattan!

Dog-walking, however, was no drudgery for him, because he loves animals. When he was two, we got him a small male Boston terrier, named Medor. Medor lived to the age of twelve. When he died, Tony begged for another pet. We went down to the pound and picked up a short-haired, part-terrier, mostly mongrel pup. Tony named him Skippy and spent endless hours teaching him tricks. It broke Tony’s heart to part with Skippy, but when he decided to go to college in Florida, he had to. He searched among his acquaintances and finally gave Skippy to a little boy who also loved dogs. Today, Tony has another dog, Punky, an indescribable mixture of breeds. Where did he get him? At the pound, of course. And Tony does his own dog-walking.

Even as a boy, he followed through conscientiously on his small money-making projects. He’s like that now about anything that seems important to him. When he begins to read a book and finds it interesting, he can’t go to sleep or to an appointment until he’s finished reading. He’s even passed up parties. If he hears a song on the radio and likes it, but has missed the beginning, he’ll head for the nearest record shop and hunt stubbornly until he can hear the whole song. When he starts a meal he enjoys, he can’t stop eating until he’s full. He can’t turn an album off in the middle, and he can’t leave a story or a letter half-written. So, when he decided to become an actor, he couldn’t stop until he got where he wanted to go. (And I don’t think he’s there yet, but with my son I can’t be sure.)

Osgood Perkins was a fine actor on the stage in “The Front Page” and “Goodbye Again,” on the screen in “Scarface.” But until Tony was twelve or thirteen, I had no idea that he wanted to be an actor like his father. There were all those other enthusiasms, you remember. Then, slowly, I began to realize that he was acquiring an unusual interest in the theater and in performing. By the time he was fifteen, I was certain. A friend was running a summer-stock company, and I approached him to ask whether Tony might play some small parts. My friend agreed if I would go, too, and hold down the boxoffice. Yet up to this point Tony, reserved as ever, hadn’t expressed any wish to act. We were driving up to the playhouse when I asked, “Would you like to appear in some of the plays?”

“Well . . .” Tony looked away from me, out the window. “. . . I guess so,” he said softly.

Tony did three roles that year and appeared in stock every summer until 1953. Acting became his vacation, but I still didn’t realize that he was considering it his vocation. As with so many things that he wants very badly, he never gives a clue to show how much he does want them. He was putting on the greasepaint in high school, too, and dreaming of enrolling at Harvard, his father’s alma mater, where he could take theater courses. But, with his inconsistent work habits, he hadn’t made grades high enough to meet Harvard’s exacting standards.

“It’s all right, Mother,” he said, believing he was covering up his disappointment. “I’ll go down to Rollins College in Florida. They have a very good drama department there.”

So the theater bug had bitten! Even then, I wasn’t sure the effect would last. But I learned the truth in 1953, while I was in Europe and Tony was only one semester away from graduation. I received a letter from him: “I’m transferring to Columbia University, so I can be in New York and really get into the acting business.”

Then I knew, and I wondered how much attention his Columbia studies would get. Anyhow, I was delighted that he had had three and a half years of college—more than I had expected. Just the same, I was worried about him. I’d been around the theater long enough to be familiar with the problems of young people trying to break into show business: the insecurity, the disappointments, the small percentage of people who become “somebody” or even manage to make a decent living. I wondered how all these would affect a shy and sensitive boy, in a world where these qualities take a constant beating. But I was too far away to do anything about it—and I don’t think I would have been able to, in any case. Tony had made his decision.

He went to New York that summer and started knocking on doors. He had decided television would be the easiest medium in which to start, and he tried to get on just about every TV show on the air. In each letter I received, Tony tried to sound cheerful and optimistic, but I could detect his frustration. The truth was that all summer he hadn’t been able to land even.a single small television role!

When I returned to New York, I was surprised to find Tony still determined to become a professional actor. It was a quiet kind of determination, a solid stubbornness. No ranting, no rash promises. Just a set-jaw attitude and a firm “I’ll make it.” I’ve seen that attitude since.

Of course, once Tony got going he was uncommonly lucky. At this point, he has achieved some of the goals he set for himself: to be on TV, on Broadway, in the movies. But he’s still unsatisfied. He wants to grow as an actor, to become one of the best in the profession. And when he does this (I’m convinced he will), there will be still other goals. Eventually, he may write and direct. His own approach to each part he plays is serious, original and carefully thought out. So, with application and time, I know he can move. into these other branches of movie-making.

Look at the way he went about his singing. Tony always loved to sing for his own enjoyment, but he didn’t talk about doing it professionally. With his customary reticence, he held back, because he wasn’t sure that he could do it well enough. Then, on the television show “Joey,” he portrayed a shy young man who wanted more than anything else to sing. Tony found a song, full of sweetness and tenderness, and sang it. His voice had a sincere, untrained, but pleasant charm, and it reflected his own personality.

Even before he came to Hollywood, he was signed by a recording company and made his first record. Without telling anybody, he continued to sing to himself and by himself. When he made his first album, everybody at the recording session was amazed to discover how much his voice had strengthened and how much command of the music he had acquired.

The natural reserve my son has always had extends to matters of appearances, too. He doesn’t believe in flashy clothes; he’s happiest in dungarees and sneakers—not because he’s making an act of being unpretentious, but simply because he believes in comfort. He likes plain food and unplush restaurants. He’s as fascinated by dime stores, as when he was a boy. He can spend a quarter at Woolworth’s and come out happier than if he’d bought gold cufflinks at Tiffany’s.

After Tony got his driver’s license, he called me from Hollywood to tell me about it and to confide that he’d always wanted a Thunderbird. “Do you think I should have one now?”

“Of course! You can afford it.”

But a year went by before Tony got up the courage to buy his Thunderbird. Remembering the days after his father died, when we didn’t have too much and often had to cut corners, he thought the car would be too much of a luxury for him. And he was afraid people might think it showy. Reticent as he is, he does have a regard for other people’s opinions; he has genuine respect for the city and the industry that have brought him such good fortune.

I remember when we were living in Cambridge, Mass., and Tony was attending high school. He’d go out with the other boys in the evenings, but he would always phone me, saying where he was going and when he would be home. One. time, he didn’t call and he didn’t show up all night. Naturally, I was worried sick.

Later, I learned what had happened. Tony and some of his pals had gone to a café a few miles out of town. The fellows sat around, drinking Cokes and playing the jukebox. When Tony noticed it was getting late, he suggested they leave. But the others weren’t ready to go. Tony ambled off by himself and, not having car, thumbed a ride. The auto broke down and Tony tried to help the man fix, it. Finally, they phoned for a mechanic; but by the time the car was repaired and, Tony had arrived within the city limits, it was two o’clock in the morning. Tony rang a school friend’s doorbell and bunked at his house that night.

“Mother,” Tony explained the next morning, “I didn’t want to come in so late and wake you.”

Tony still hates the idea of being a bother. I have a small apartment in New York, and naturally I could arrange to have my son stay with me when he’s in town. But Tony sees it differently. “l’d be getting phone calls, coming and going all hours of the day and night,” he says, “and you wouldn’t get any rest.” And that’s why Tony keeps his own tiny place in New York and I keep mine. Even this arrangement sometimes worries him. “You don’t mind, do you, Mother?” he’ll ask.

When things are really upsetting him, Tony seldom tells me. It seems he just doesn’t think anyone else should carry his burdens. While he’s making a picture abroad, he writes to me oftener than most young men would who are as busy as he is. Mostly, he isn’t much of a correspondent. If he writes a lot, then I begin to suspect that he’s unhappy or lonesome or homesick. I’d never hear this directly from him! In letters, Tony always skims over troubles, serenely thinking, I suppose, that I can’t read between the lines. When he was working on “This Bitter Earth” in Italy, he wrote that it was a little difficult to get accustomed to the Latin routine. The Italians, he said, began shooting their scenes after lunch and worked until late at night.

Well, this isn’t for Tony! He’s always one to rise early in the morning, full of energy and ideas. Even as a youngster, he had a dozen things that just had to be done before he went to school: walk the dog, play a record he’d bought the day before, try a new magic trick or think up new ways to earn money.

Tony has become a true professional, and he carries his profession with a great sense of responsibility. I like to think that his attitude stems from his heritage, his father’s career. When my husband died, we didn’t stop mentioning him. We kept his photographs around the apartment and we went on talking about him, remembering the happy times and thinking of him as an active part of our lives. As Tony grew up, he met many of his father’s colleagues, saw some of his old movies. He developed a natural appreciation for Osgood Perkins. And somehow, deep inside, Tony must have made a silent vow never to let Osgood Perkins down.

As for all the publicity that goes with his success, it seems quite natural to me. If the stories about him are good, I like them. If they aren’t, I don’t. (After all, I’m slightly prejudiced.) But the results have mostly been happy. Because of everything that’s been published about Tony, I’ve received letters from old school friends that I hadn’t heard from in thirty years. And my mother, who is eighty-seven, is kept alive by her keen interest in Tony’s work and his progress.

When I read fine reviews about Tony’s performance in “Desire Under the Elms,” for me it is like reliving the past. My husband always got wonderful notices! It all seems enjoyably normal. Yet, when Tony looked away from me that other day years ago, his voice trailing off with “I know what it is I want to be”—I couldn’t be sure just what he was thinking. When we drove up to the summer-stock playhouse, and my fifteen-year-old looked out the car window, I didn’t know what thoughts or ambitions were in his mind, either. Today, I don’t know what lies ahead for Tony, either, but I’m proud and delighted—end still a little baffled.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1958