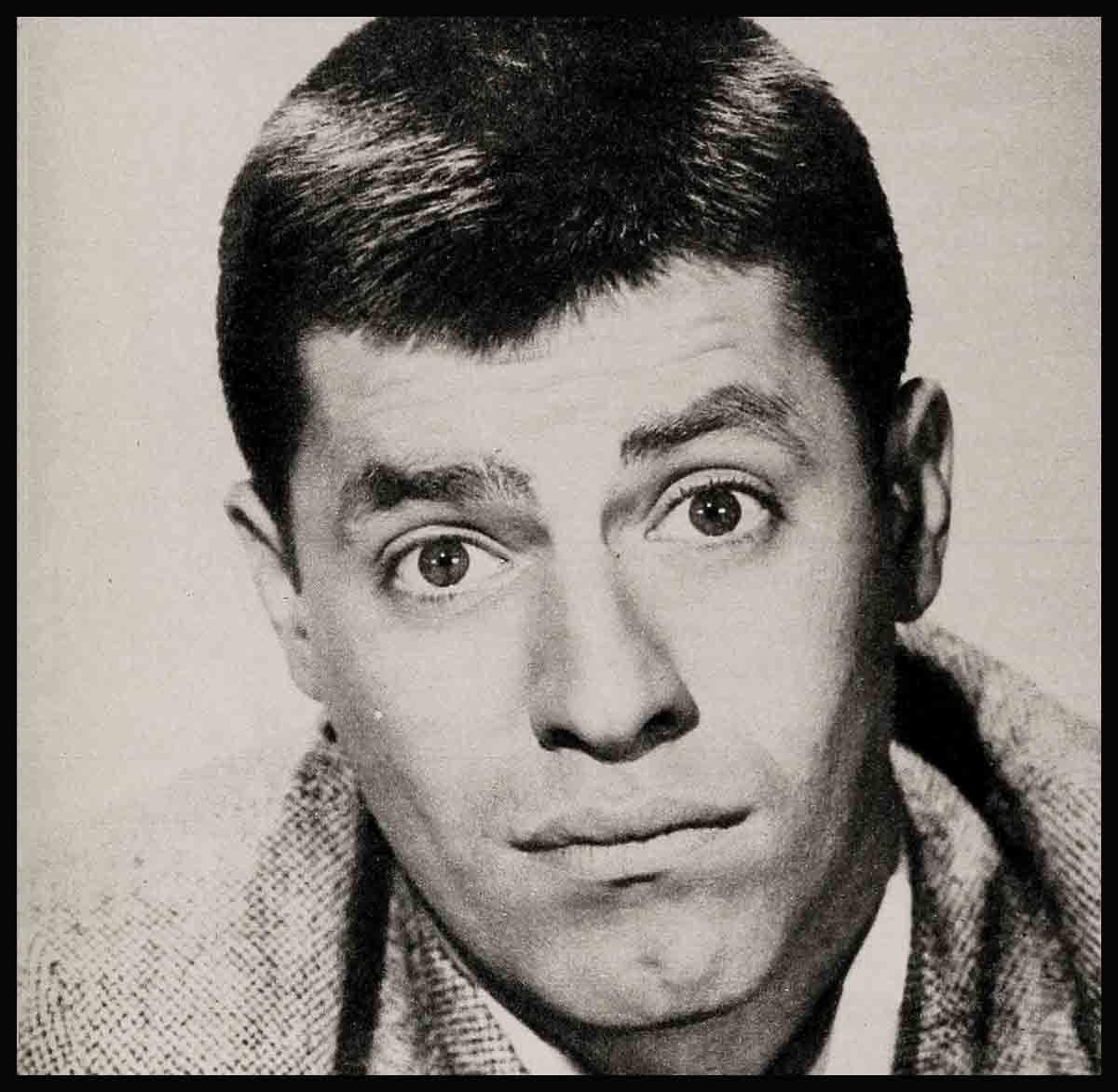

What’s Happening To Jerry Lewis?

A tide of resentment is mounting against Jerry Lewis.

Any mention of the great clown’s name used to arouse only smiles, laughter and happy memories of comic pandemonium. Now it also brings expressions of regret, puzzled head-shaking and grimaces of disillusionment.

The general opinion is that Jerry is beginning to resemble the cock who thought the sun had risen to hear him crow. His large circle of Hollywood friends is getting smaller.

Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis no longer make those riotous home movies with Jerry and his wife Patti. Mona Freeman, once a confidante, now blithely goes her own way.

Simmons and Lear, his writers, are objects of his annoyance. Although he is compelled by contract to pay them, he neither talks to them nor uses any of their material.

Jerry strongly dislikes Bob Hope. Bob doesn’t like Jerry, either.

Although Hal Wallis rescued Jerry from an unprofitable contract, Jerry’s behavior now borders on loud-mouthed hatred.

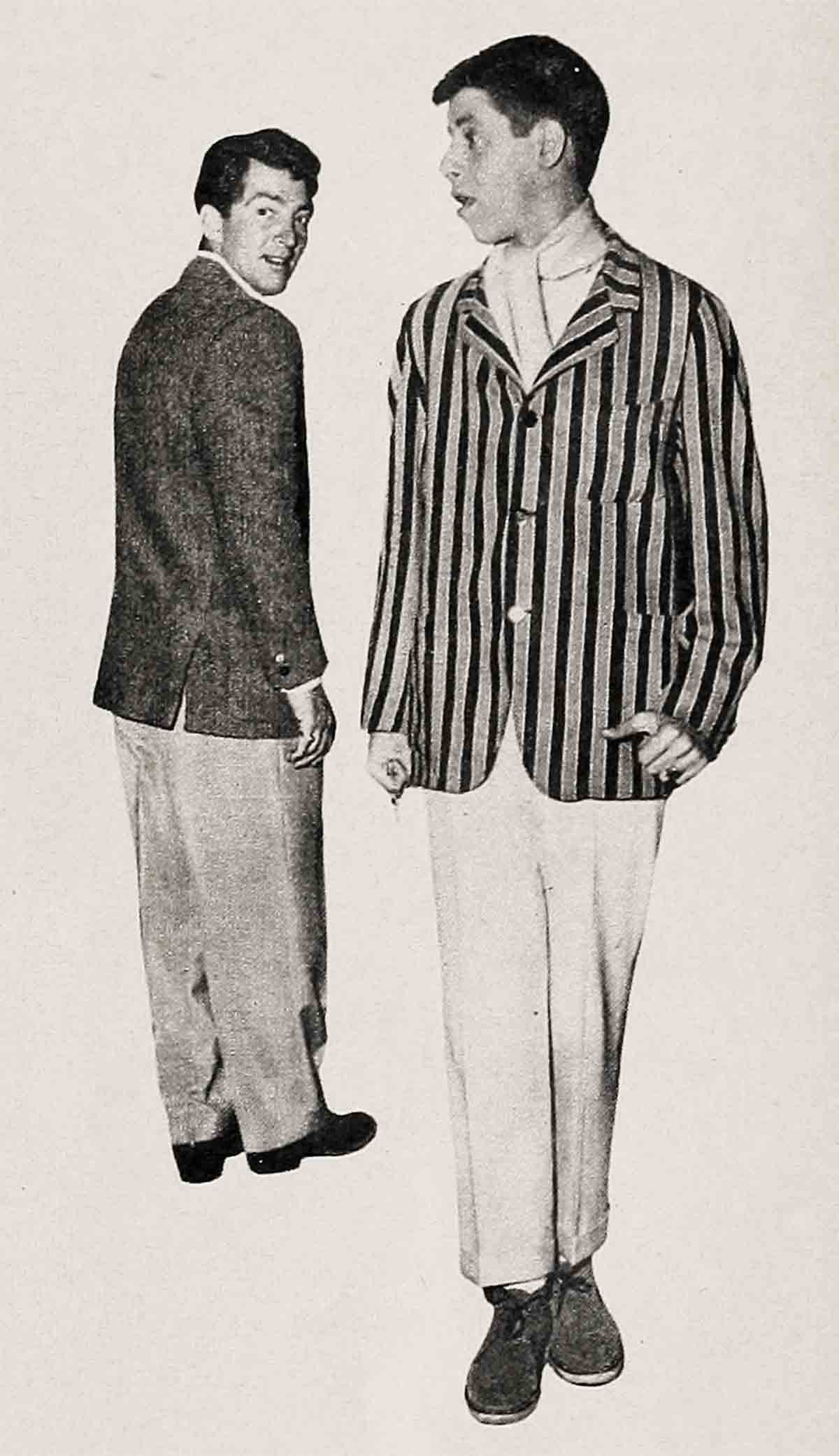

Worse yet, there are signs of family warfare in the Martin and Lewis camp.

While the comedians were in Phoenix on location for The Big Top a national magazine was shooting a picture spread on Jerry. Apparently chagrined that he had been overlooked, Dean simply disappeared from the set, holding up production of the picture.

It had been no secret, of course, that Jerry’s wife Patti and Dean’s wife Jeanne avoid each other socially. Now it looks as though their resentment is spreading to the boys.

Until lately, Dean has always seemed to be content to play golf, relax, enjoy himself—and leave professional problems and decisions to “Jer.” Now he’s taking an interest.

He, too, could be suffering from a little head expansion. A few weeks ago a Hollywood composer dropped by Dean’s house. He had a new tune he thought would be just right for Dean. This composer has written almost as many hits as Irving Berlin and he doesn’t need Dean Martin to sing his numbers. But he’s thoughtful and naturally he expected Dean to appreciate his gesture.

When Dean was told that the composer was downstairs he turned to Killer Gray, his aide-de-camp, and said, “Can’t see him now. Let him leave the sheet music.”

When the composer got the message, he grabbed the sheet music out of Killers hand.

“Tell him for me that if he doesn’t have the courtesy to come down and say hello—” his speech began.

Still, Martin has not offended by untoward behavior nearly so much as Lewis. Not long ago, Lewis, accompanied by his gang stalked into the Paramount commissary. As usual, Jerry began to shout and cavort. A veteran studio employee was entertaining a guest. He leaned over and said politely, “How about taking it easy? We can’t hear ourselves talk.”

“Look,” snapped Jerry, “if it weren’t for me and my partner you wouldn’t be working here. We’re keeping things going.”

There are similar stories emanating from the wardrobe, publicity and script departments—all showing that Jerry Lewis is feeling his oats.

Jerry wants to sing ballads in his pictures that should logically be sung by the heroine—or by Dean Martin. And he was so furious about the script of The Big Top that he didn’t want to make the picture. It wasn’t until Hal Wallis threatened to take the boys off television and cancel their personal appearances and recording dates that Jerry got back in line.

The rubber-faced comedian’s friendship with Janet and Tony Curtis has also cooled. The two young couples were all but inseparable for a couple of years. Patti and Jerry stood up for Janet and Tony when they were married. Almost every weekend found the Curtises out in Pacific Palisades with the Lewises.

Now? Well, you won’t get either pair to admit that there’s any friction. But last New Year’s Eve there was a party at the Curtises—and Janet hadn’t remembered the Lewises. The same night there was a party at the Lewis house and the Curtises weren’t asked.

Rapidly, rumors of feud spread through the movie colony: Jerry’s press agent even advised the Lewises and the Curtises to make the rounds of the night spots together just to kill off some of the talk.

MODERN SCREEN raises the discussion of Jerry’s behavior because we have long admired his great talent and considered him a fine human being. We wouldn’t want him to change.

Jerry has contributed untold time and money to charity and to the victims of muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, infantile paralysis and other diseases. He has been fined by his union for giving benefit performances without permission. Surely, he has spent thousands of dollars on other people.

We are convinced of Jerry’s virtues and we hate to see him unwittingly antagonize his fellow employees.

Al Jolson did that kind of thing as a young man. In spite of his tremendous stature and remarkable public popularity he was once intensely disliked by those who worked with him. We don’t want to see this happen to Jerry Lewis.

We hope Jerry won’t need to reassure himself about his own value by behaving in a brash and dictatorial way—by appointing himself an authority on music, comedy, and story values—and by losing his friends.

Jerry is a kind, warm-hearted, considerate person. He could become one of our loved, admired and respected comedians.

It must be remembered that Jerry has been under a great strain since he reed from Europe last summer. He has finished three motion pictures, starred in half a dozen TV shows, appeared at the Copacabana in New York and played countless benefits and dinners.

Jerry pushes himself, driving his meager physical resources to the limit. He ignores his physician’s advice and works until he becomes nervous and irritable.

After earning so much money, it seems incredible that Martin and Lewis could be in debt both to the U. S. Government and to Paramount Pictures. They have already paid back more than $750,000, but they spend a remarkable amount of money. Jerry can’t buy one pair of slacks or one pair of socks; it’s got to be half a dozen in all colors. Dean’s support payments to his first wife come to more than $3,000 a month. Between them, they keep twenty-three people on their payroll. You can see how tough it is for them to try to get even now.

According to some old friends, his financial situation is not responsible for Jerry’s domineering ways. Others think that’s part of it.

“Look,” one of them said, “I remember that kid from the 500 Club in Atlantic City. In 1946 his act consisted of mugging to phonograph records. His wife was in the hospital with a new baby and he didn’t have the dough to bail her out.

“I don’t want to use an overworked line, but the kid was very humble then. Very nice and very grateful for anything good that came along.

“Three years later he was earning $15,000 a week. The hangers-on were gathering around him, and—well—the setup went to his head. He’s only twenty-seven, after all. It’s only natural.”

An actress who used to be his pal and no longer is, says, “Jerry Lewis is a contradictory guy—a strange guy. One minute he’s warmhearted and generous. The next he’s fighting and quarreling.

“You’ve got to remember that his success came quickly. By the time he was twenty-two or twenty-three he was earning close to a half million a year. Under circumstances like that it takes great strength of character to keep a level head and a civil tongue. Jerry has begun to throw his weight around.

“Dean’s wife recognized that early in the game. She felt and she still feels that Dean is 50% of the act and is entitled to 50% of the attention. That rubbed Jerry the wrong way, and that’s why his wife and Jeannie don’t mix. That’s the way it looked to me, anyway.

“I’ve seen only one man put Jerry in his place—Hal Wallis. Unfortunately, both Dean and Jerry would like to get out of their contracts with Wallis. It’s no secret that they’ve been more than dissatisfied. They believe they’re being exploited in lousy pictures. Actually, their movies have been grossing less and less. It’s difficult to find story material for them, but by contract they’ve got another four or five years to go with Wallis. Maybe that’s one reason Jerry has been rather disagreeable of late.” But the actress knows Wallis, too.

She said, “There’s another side of the coin. Wallis is a producer of stature and experience. The boys have achieved their greatest popularity under his wing.

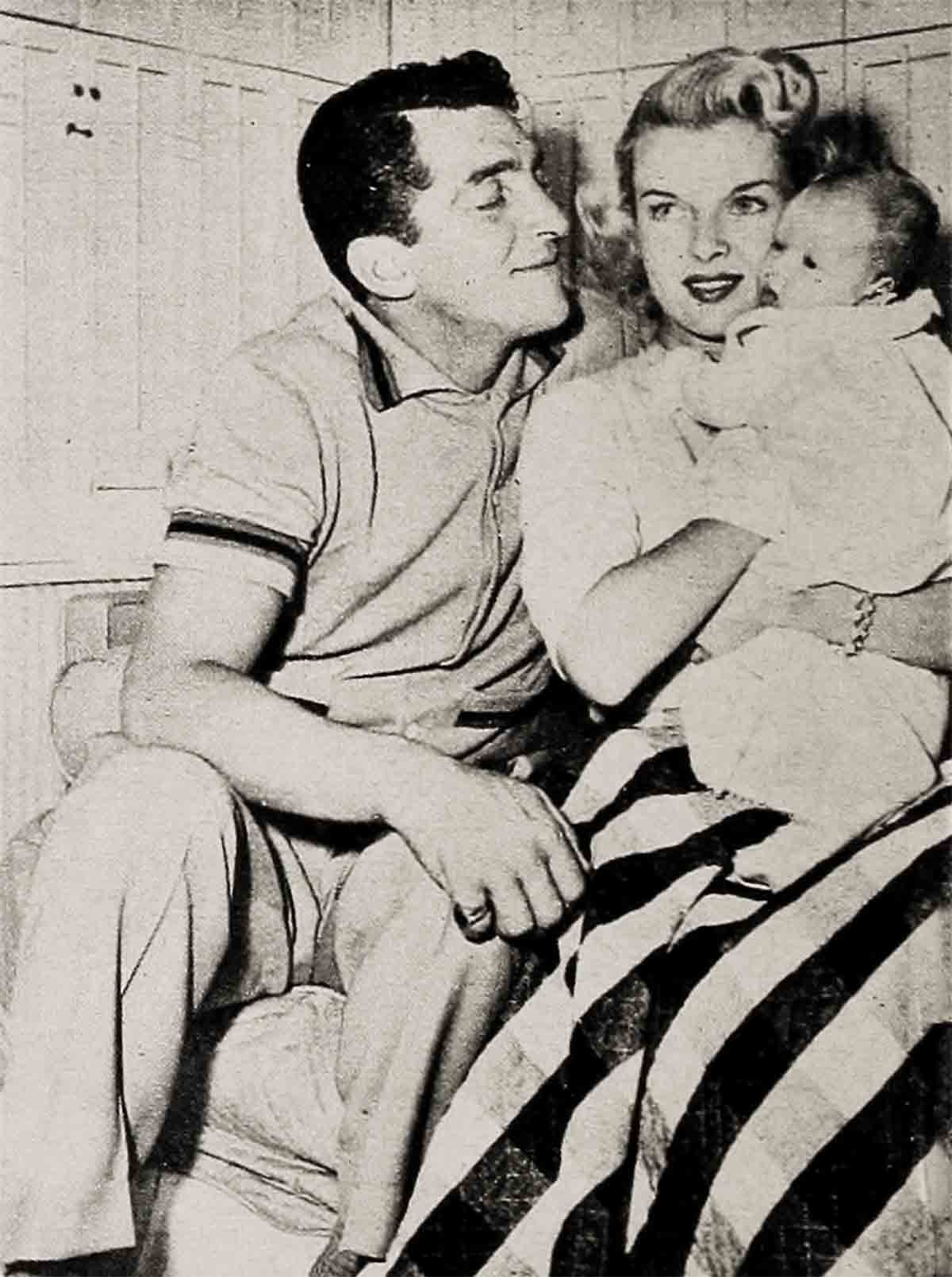

“Jerry is lucky to be married to Patti. There’s a young woman with both feet on the ground. If it weren’t for Patti I think Jerry would be completely unmanageable. She’s a settling influence—it was she who got him to the point of sleeping without a gun under his pillow—and if anybody cai keep him in line, Patti can.”

Jerry likes to say, “I wasn’t brought by the stork. The bat brought me.” He was named Joseph Levitch when he was born in 1926 to a pair of vaudevillians, Danny and Rea Lewis.

Jerry was brought up in Newark, mostly by his grandmother and his aunt. His parents were on the road most of the time and he felt so lonely and unhappy that he hasn’t been able to recover to this day. Probably that’s why he has surrounded himself with yes-men and why he cannot abide being alone.

He never really had a definite home. During summer vacations he used to work as a bus boy in resort hotels where his parents were entertaining. At Brown’s Hotel in the Catskills he put on a wig and began to do imitations. Irving Kaye, a local comedian, heard Jerry, thought he was hilarious and got him a job in a Buffalo burlesque house.

When the scared fifteen-year-old boy trotted on stage for his debut, the hardened customers shouted their disapproval. “Get off! Bring on the dames!” Jerry started to cry and ran to the wings. Max Coleman, a friend of Jerry’s father, persuaded the boy to go back and finish his act.

With such a rocky start, it’s no wonder Jerry needs constant encouragement and admiration from those around him. He surrounds himself with employees who won’t speak up when Jerry steps out of line, either because they don’t know or because they won’t take a chance on Jerry’s reaction. As a boy, Jerry felt inferior too many times to hazard that experience again.

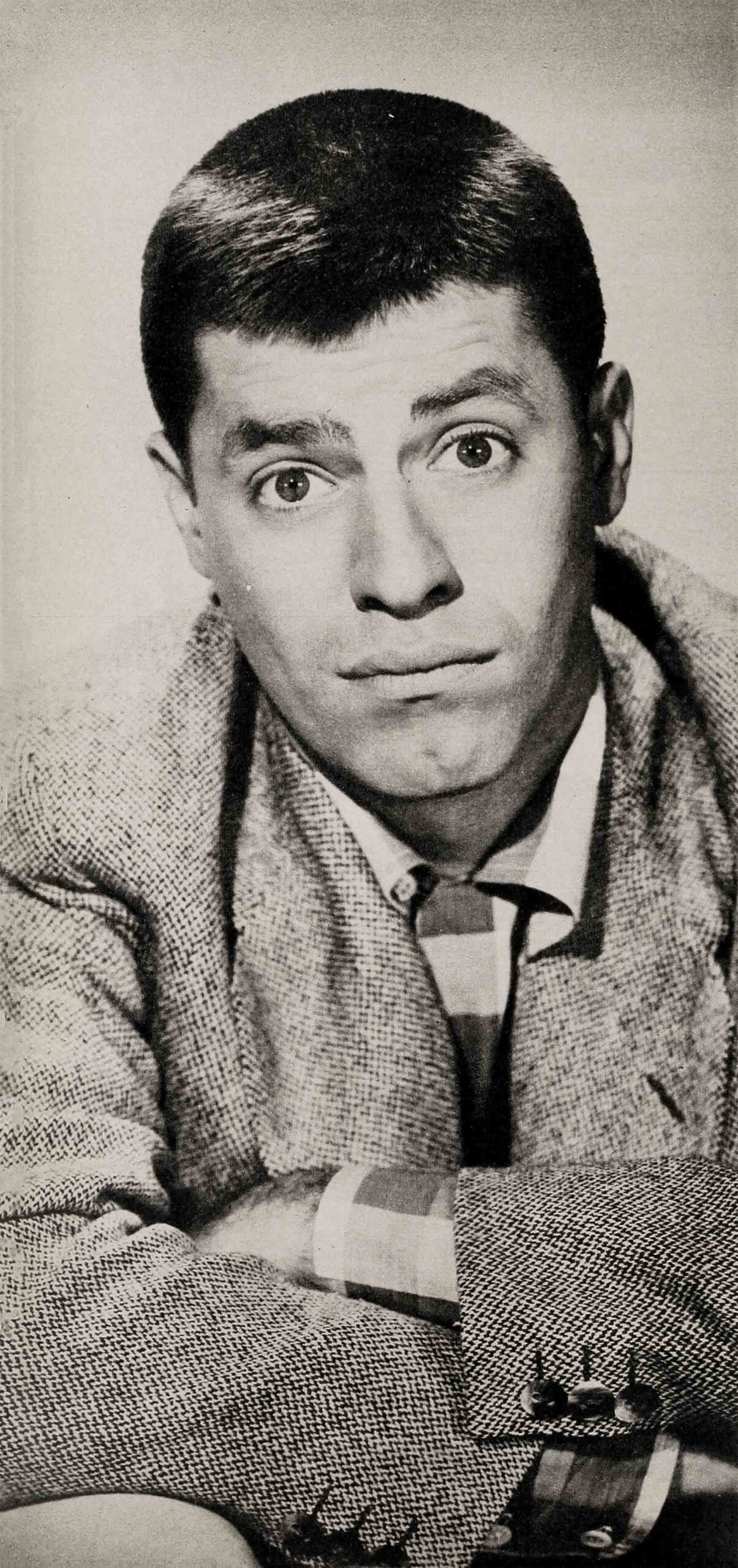

Essentially, Jerry is a moody, melancholy young man with a genius for mimicry that can take him out of his depression into the world of responsive laughter. So, again, he must have an audience.

The Lewis house is usually filled with people—Patti never knows how many will stay for dinner—all assuring Jerry that he is the greatest. He demands boundless loyalty of his friends. He gets jobs for acquaintances, gives them money, puts them on his payroll. In return he expects slavish devotion over and above the bounds of normal gratitude. Apparently, he has not yet realized that this is too much to ask. People can’t give it. If they could, it wouldn’t be worth much.

When they refuse to build their lives with Jerry as the cornerstone, there is bitterness and tapering-off friendship.

Under Jerry’s wackiness there is perception and shrewdness. Probably he knows what’s happening, but he does not or cannot stop it.

He knows he should relax, vacation, enjoy himself, but he doesn’t. Maybe he can’t. He loves to entertain. He is compassionate, generous, humanitarian and—like all great entertainers—stubborn and self-centered. Many Paramount employees will testify that he has done more for people than any actor on the lot. He is genuinely and deeply loved. It is a shame that a young man who formerly had only friends should now have enemies, too.

Of the explanations for this untoward behavior of late, probably the most valid is that Jerry and Dean are unhappy about their work in Hollywood. Several months ago they tried to buy back their contract. Hal Wallis wouldn’t sell.

Since then, Jerry’s temperament has been showing.

THE END

—BY STEVE CRONIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1954