A Shy Girl Discovers The Joys Of Love—Marisa Pavan

A couple of months ago, MODERN SCREEN referred to Marisa Pavan as “The dark one, the quiet one.” And she was, too. A shy, silent girl with large sad eyes, beginning to make a career for herself, but still living on the fringe of her sister’s life, spending her time with her sister’s gay young friends, and feeling desolately alone among them. A girl whose bright inquiring mind had been denied the university career for which it was trained, whose love of books and music was lost in the world of sports cars and night clubs and success (even her own) into which her sister, with the best intentions, had led her.

A couple of months ago, the spark and the brightness were the property of Pier Angeli, and Marisa Pavan made do with the lonely virtues of dignity and poise.

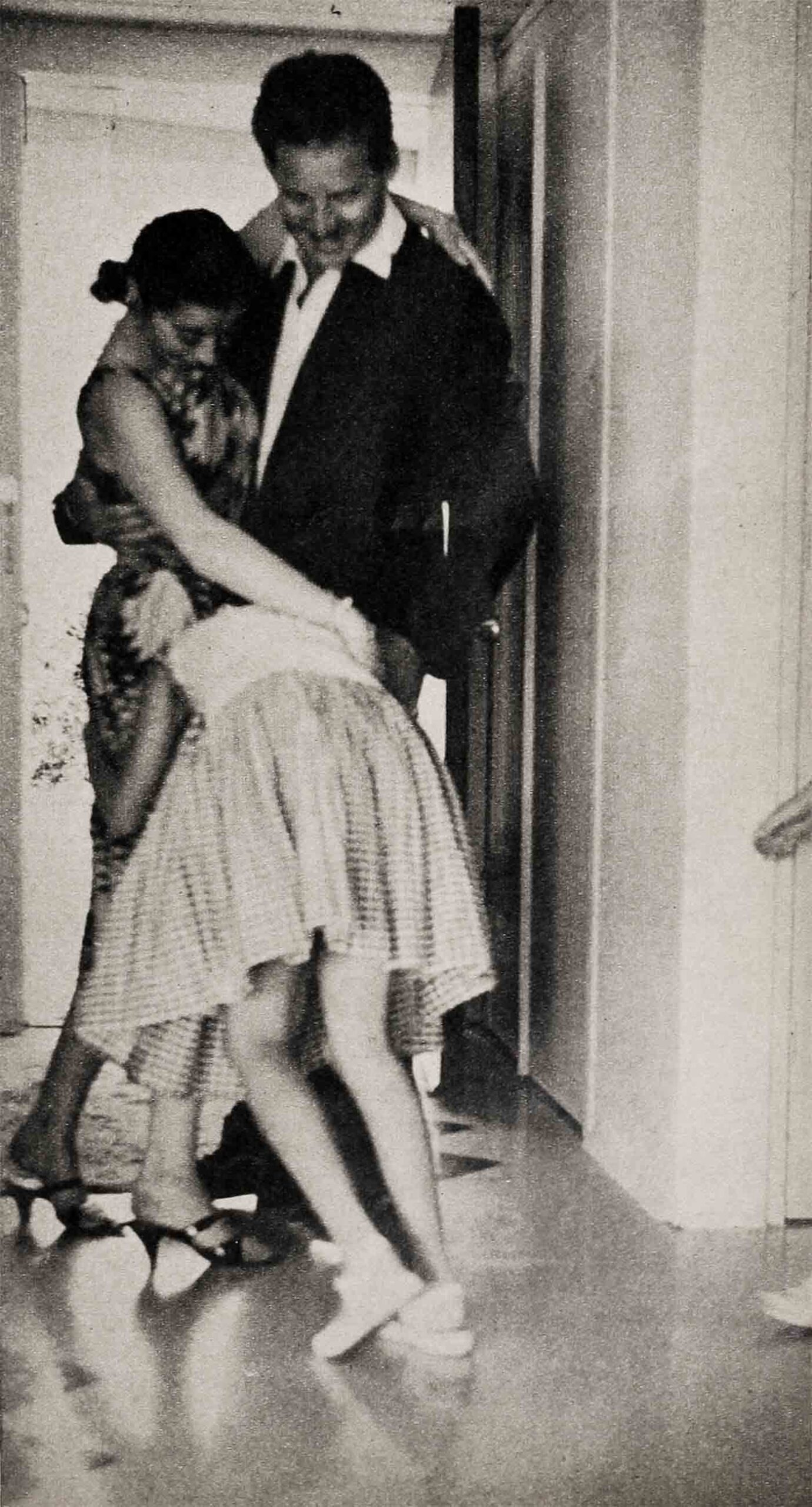

But today Marisa is a girl transformed, a sprite compounded of laughter and glow and shouting joy, a radiant, shining creature. And to put it simply—the cause was a miracle that took three years in the making.

For it was a little less than three years ago that Marisa met Jean-Pierre Aumont.

Back then she was Marisa Pierangeli, who had still to be noticed by anybody at all, and as usual, she was tagging along on a spree of Pier’s. This time it was to Paris. And as usual it was Pier who dashed happily about from theatre to theatre, seeing the shows and meeting the stars, while Marisa, by choice, roamed through the museums and bought tickets to the operas. But one night Pier came home so excited she could hardly talk. She had been to a show and she had seen Jean-Pierre Aumont. He was absolutely the most wonderful thing in Paris, so handsome, so charming. Of course she had gone backstage afterwards to say hello and in person he was even more wonderful—simply a delight. Marisa must tear herself away from her sight-seeing and come too. So must Mama. She, Pier, would adore to go again, and afterwards they would all go backstage. Would they?

They certainly would. Mama because she loved the theatre, and Marisa because—because all of a sudden, sitting there with her dark eyes shining, she wanted very much to meet Jean-Pierre Aumont. A real actor, not a glamour-boy. A man everyone talked of with respect and love. A man who had lost a wife he adored and who had recovered from despair to make a life for himself and his daughter. Marisa thrilled to the prospect of the meeting. For once—a really exciting man!

But when the great moment came, and after watching the play for an enthralled three hours they were ushered into his dressing room, Marisa was shy. After all, what was she doing there? Pier had every right to chat with a fellow-artist, and Mama would get along anywhere, but who was Marisa, with her skimpy French and worse English? A bystander, that was all. Of course, Jean-Pierre was most charming. He talked to her for quite a long time, and if he was bored at what she’d been doing in Paris, or surprised that she had seen Napoleon’s tomb instead of the Folies Bergére, he had the tact not to say so. And of course she could tell him how wonderful he was in the play—but she couldn’t rhapsodize like Pier, or discuss the technical problems of the show, or laugh the way Pier could, so lightly and joyously and easily, at his wit. So when Jean-Pierre turned his attention back to her bubbling, beautiful sister, that was to be expected. All men loved Pier. Why not? So sweet and pretty and good. She did seem, Marisa reflected, watching, just a little young for Jean-Pierre Aumont, who had lived so much—but then, maybe Pier was just what he needed to take the sorrow out of his eyes.

So you could have knocked her over with a feather when Jean-Pierre phoned the next day and asked if she, Marisa Pierangeli, would have dinner with him.

The first date

That was how the miracle began. Very quietly at first, so that no one, especially Marisa, could have told what was happening. Why, she couldn’t even tell what happened on her date. She got home at a respectable hour and let herself in with the brand-new key that had been given to her on her twenty-first birthday, and she found Pier and Mama sitting up waiting for her. The minute she shut the door they descended on her like a pair of vultures. “Well?”

“Well what?”

“Where did you go?”

Marisa thought. “Oh. To dinner. A very nice place. . .”

“Yes?”

“And then for a walk. . . .”

Pier was dancing with impatience. “Tell us what happened. Tell us all about it!”

Marisa sighed. “Well, we had a shrimp cocktail and then soup and then . . .”

“Not that, you idiot! What did you do? What did you talk about?”

Marisa paused. “I don’t exactly know,” she said slowly. The dark lashes lowered while she concentrated. “Oh, yes!” she said. “We talked about Mozart!”

“Oh, Marisa, for heaven’s sake . . .”

But Marisa was half way out of the room, on her way to bed. At the door she turned to look back. “Good night,’ she said. “I had a simply wonderful time . . .”

And that was all anyone got out of her, that time or the next or the next. For they saw each other three times in that brief week before they said goodbye and Marisa packed her bags to follow Pier home to Hollywood. When they parted they made no plans to write to each other. Their goodbyes were a little sad, but not heartbreaking. They had had fun together, but that was all. Neither of them knew that the miracle was begun.

But Marisa, from that first date on, walked with a firmer step. She, the ugly duckling, had been chosen over Pier for the attentions of a man any girl would give her eyeteeth to date. And she hadn’t had to act a part, she hadn’t been one bit phony. She’d been Marisa, that was all, and he liked it. They’d talked about authors and music and painting and all the things she loved best—and he had known about them from ’way back. He had told her about his daughter—such a beautiful little girl in his photos—and she had seen the tenderness and the concern in his eyes, and she knew he was really interested in what she had to say about her young sister Patriza, who was almost the same age as Jean-Pierre’s Tina. And when they talked about her, Marisa, he had listened gravely to the interrupted dream her life story was, and he had told her that it wasn’t over—that she could have a different dream and make it come true. She could make her own place in this new world in which she had to live, he’d said. Of course it would take work. She’d have to improve her English and overcome her fear of competing with Pier. She’d have to go out and go after the things she wanted, but it could be done.

His words echoed and re-echoed in her head. On the way back to America, Marisa made up her mind. She would talk to that man who wanted to give her a screen test. She would stop sulking about what she could not change and make something good out of what had to be. And she could do it now, though she could not have before, because a boyish-looking man with sad eyes had shown her that she didn’t have to be Pier, or anyone else, to be somebody. She would be Marisa, whom Jean-Pierre Aumont had liked. She could do anything.

And for Jean-Pierre, the miracle was this: he knew he could love again. It had been years since Maria Montez’ death, but he had never ceased to mourn. At the beginning it was almost more than he could bear. His child, Maria Christina, alone kept him from utter despair. Later he was able to go back to his work, and find forgetfulness for a while in that. But his heart was closed to all but his daughter. When he needed a date, he made one with a friend, or with a starlet who would be happy to be photographed with him—and that was the end.

But Marisa was different. Marisa he had called because he wanted to see her. He had found no need to take her where they would be entertained—he merely wanted to talk to her. He found pleasure in her company, and when he made her laugh—that deep laugh coming from a depth of joy no one had ever really seen in her—his heart responded with equal joy. He saw so much in her—secrets behind the dark eyes, talent in her quick perceptions, and that hidden well of happiness covered presently by her discontent.

When Marisa left, Jean-Pierre realized that he had awakened once more to life.

Then he met Grace Kelly.

People said three years later when JeanPierre married Marisa that she reminded him of Grace. But the truth is this: Grace reminded him of Marisa.

Grace, too, was cool and poised in a silence that might be haughtiness but was more likely shyness. She, too, would explode from time to time with a sudden, unexpected glee, almost like a little girl. Only this time it was Grace instead of Marisa; this time he was ready for love.

But that is why, when the idyll with Grace was over for Jean-Pierre and he came to Hollywood again, he and Marisa were ready for each other.

“We meet again . . .”

Marisa by then was a star. She had done what he had told her to do, and it had succeeded—just as he had said. She was, professionally, out from under Pier’s shadow—she had made her place in the sun. Now she needed only her sort of people. This time when the phone rang and Jean-Pierre asked for her, she had no terrors. Just joy. She had read about his romance with Grace, and frankly, she had been—how can it be said—just a little pleased that it came to nothing. That she had been indirectly responsible for it, she had no idea. But now it was over, and now Jean-Pierre was in Hollywood, and he wanted her to come to dinner. And to bring Mama and Pier if she liked, and anyone else. There began to grow in Marisa’s eyes the glow of happiness and love.

Because right from that first evening at Jean-Pierre’s home, they both knew. And the next night when he took Marisa to a premiere. And the night after, when he phoned, and the night after that when they saw each other again and felt that they had been parted for years!

On the fourth date, Jean-Pierre proposed. Well, it wasn’t a real proposal—because even though both of them knew that they would be in love and be married, it was still so very soon. So he made a joke out of it. “When we’re married . . .” he would tell Marisa, and go on to elaborate the marvelous things they would do. And Marisa would agree, “Of course, when we have our third child . . .” and continue the jest that wasn’t a jest at all.

When a month was up, they stopped joking. “Would you marry me, Marisa,” said Jean-Pierre across the dinner table, very seriously. Marisa laughed with the new laughter that came to her so easily now. “I’d love to,” she said, watching the sadness leave Jean-Pierre’s eyes forever.

“So soon?”

And so they went home to tell Mama about it. Mama was a little nervous. She liked Jean-Pierre just fine. She liked the new light in Marisa’s eyes even better. But—“So soon?” said Mama. “You hardly know each other. Better to wait.”

“Wait for what?” said Marisa. “We know each other quite well. We are in love. We want to marry.”

“Good,” said Mama, “marry. But not yet. Wait just a little bit. Don’t tell people so fast.” She smiled at her son-in-law-to-be, who is forty-three years old. “I know you are not irresponsible children, but . . .”

“We will wait a little,” said Jean-Pierre. “Because there is someone else I must tell. And in the meantime, we kids will say we are going steady.” And so they did.

“Maria—this is Marisa”

The next day Jean-Pierre flew to New York, to his daughter. When he had come to America earlier in the year he had brought her with him. Partly because she was forgetting the English she had spoken with her Mama, partly to visit her grandparents in New York, but mostly because wherever he was, he needed her with him. A beautiful little girl, ten years old, who watched over him like a mother and adored him like a petted child. A child so bright that though she had lost some of her English she went right into her own grade in a New York school, and got high marks from the beginning. Jean-Pierre arrived in New York to be greeted with hugs and ecstasy. “I’m taking you out of school for a few days,” he told her. “I want you to come to California and meet somebody.”

In California she met Marisa. Maria Christina, not knowing yet about the marriage, was totally at ease. Marisa was excited, but not nervous. Just as she had known “from forever” that she would love Jean-Pierre, she knew she would love his Tina. From the first moment, they were friends. They even looked alike a little, both so beautiful and dark. And Marisa was far from a stranger to children—had it not been she who stayed home with Patriza through those years—how far away they seemed now—when she had been the ugly duckling?

That night, Jean-Pierre told Tina that he wanted to marry Marisa. And because the fates had decreed that nothing should spoil their perfect miracle, Tina flew into his arms, mingling French and English. “Qh—Papa—je suis—so glad!” The next day she dashed into Marisa’s arms with promises to learn Italian as well.

And then, back in New York, Dorothy Kilgallen announced in her column that Marisa Pavan and Jean-Pierre Aumont were engaged to be married. No one knew where she got her information—no one outside of the family was supposed to know anything at all. But while any other Hollywood couple would have wept over the loss of their privacy, to Jean-Pierre and Marisa it was a blessing in no disguise at all. “Now,” said Jean-Pierre reasonably to Mama Pierangeli, “what should we wait for? Tina knows, you know, and now the whole world knows. Besides, I just happen to have the engagement ring with me, and why shouldn’t Marisa wear it? And besides that—I would like to have Tina at my wedding, and I cannot take her out of school again, now can I?”

It was that last that did it. Mama Pierangeli had not brought up three children to pull them out of classes for little things like weddings every day. As long as Tina was here—well, the wedding might just as well take place.

And everybody cried . . .

They went to Santa Barbara for it. Marisa wore a white shantung suit and the bridegroom wore blue. Irving Thaw of MGM, a close mutual friend, was the best man, and Pier carried her bouquet as matron of honor. It was the weepiest wedding anyone had ever seen—except that no one could see anything for the tears. Mama cried, sentimental Pier sniffled, Marisa wept buckets, and the judge himself came close to breaking down. Only Patriza and Tina stayed dry-eyed, disgusted with all this inappropriate nonsense on the part of the grownups. “Aren’t you happy?” they demanded. “What are you crying for? Nobody died . . .”

The next day the honeymoon began. They took off for Hawaii and in the ladies’ room at the San Francisco airport, Marisa lost her engagement ring. She had taken it off to wash her hands, and just forgot about it. “I’m not used to wearing anything on my right hand,” she explained miserably to Jean-Pierre while the plane waited for the searchers to come back ten minutes later, “and I have to wear it there now that I have the wedding ring on my left.” The search was unsuccessful; the plane left an hour late, with the Aumonts, but minus the ring. “It was so beautiful,” Marisa mourned. “Shaped like a rose, so pretty . . . and to think you designed it and I lost it . . .”

Two weeks later the person who had found the ring read about it in the paper and sent word to the Aumonts. They picked it up on the last leg of the honeymoon flight back home. “You must have been inconsolable,” the reporters said to Marisa as she slipped it on her finger. She gazed at them, astonished. “Oh, no,” she said. “Jean-Pierre made me forget all about it. You see how wonderful he is . . .?”

And that is the way it is for them now. Everything that would have been a disaster for others was a blessing to them. Everything that made them wrong for other people made them right for themselves. Everything that is good and golden has come to them and made its change in their lives. The laughter that pours from them, the happiness that fills the air around them, are things of beauty. The joy of Jean-Pierre, who has found a second happiness to match his first. The radiance of Marisa Pavan, who, when she walks into a room, makes the other girls fade quietly into the wallpaper.

And that is the way it should be, for two people who were picked to have a miracle done to them.

THE END

—BY SUSAN WENDER

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1956