High Road To Happiness—Ann Blyth

They’re hoping the new baby will be here for Christmas. They’re no less thrilled over the second than the first. Ann doesn’t have to say so. The lovely way her face lights up speaks for her. “It’s a new miracle,” she adds simply, “every time it happens. Another link in that precious little family circle.” They’d love to have a daughter, but a son will be just as welcome. They’ve already picked probable names—Terence Michael or Maureen Ann—Ann for Ann’s mother, whose real name it was, though she was always called Nan.

Her mother’s love, her mother’s influence surrounds Ann always. At St. Vincent’s Hospital last year after Timothy was born, the past stepped strangely forward to join hands with the present. On a quiet evening one of the Sisters came in. Ann smiled in greeting, and felt suddenly that this was no casual visit, that something significant was about to happen.

The nun drew up a chair. “I’d been hoping to catch you alone for a few minutes. I’ve long wanted to write to you, but I am glad now that I waited. For I have a story to tell you and this seems a most appropriate time.

“It goes back to when I was a child in rather poor health and was sent to stay with my grandmother in New York. She lived close to where you and your mother and sister lived on East 49th Street. One day I went to the candy store where you used to buy candy and ice cream—do you remember?”

“How well I remember!” breathed Ann. “I remember the owner. He knew my Mommy.”

“Exactly. He knew how religious she was and how she loved praying for other people. She happened to be in the store that day. He said to her, ‘This little girl hasn’t been very well.’ I’ll never forget her look of loving kindness as she asked me my name and where my grandmother lived. “I’ll say a very special prayer for you, she promised, and the promise gave me comfort. A few days later someone knocked at our door. It was your mother. She’d brought me a little gold medal of the Blessed Virgin and Jesus, Her Son—on a gold chain, so I could wear it around my neck. She’d had my initials engraved on the back. I wore it for years.”

Out of her pocket she drew a small tissue-wrapped object and laid it in Ann’s hand. “To be quite honest, I hate giving it up. It means a great deal to me. But I feel still more strongly that it belongs to you now.”

Eyes blurring, Ann tried to thank her. She was grateful that no one else came to see her that night. Shaken by memories sad and sweet, she needed solitude. Alone, she unwrapped the medal with its holy figures, turned it over and stared incredulously. For the initials of that long-ago little girl had been A.M.—which stood for her own name, too—Ann Marie. Her heart lifted in almost unbearable thanksgiving. To Ann this was no coincidence, but God’s mysterious way of performing His wonders. It was like a gift from Him through His servant and like a benediction from her mother on Timothy’s birth.

“She was my great inspiration,” says Ann. “By her teaching, by her example. By her supreme gentleness and compassion. She had the kind of charity that doesn’t presume to judge. And a faith that never failed. This was her strength, and she did her best to instill it in me. Often when I’d read for a part I didn’t get and maybe grow a little disheartened, she’d put me right. ‘Setbacks are a necessary part of life, they make you try harder, they help to build character.’ Most of all, she’d say over and over again: ‘God in His wisdom has a reason for what He does and He always knows best. Even though the reasons may be difficult for us to understand.’ ” Ann paused for a moment, looking back. “There are some things we never will understand. But we accept them as part of His plan. That was the essence of my mother’s faith. It’s the essence of mine.”

So her childhood was spent in an atmosphere of love and faith, fostered both at home and in the Catholic school she attended. It was therefore a happy childhood, despite hardship. Their father had left home while the girls were little. Ann barely remembers him. Mrs. Blyth worked as a laundress, as a hair stylist, at whatever she could find. “She had beautiful, talented hands,” her daughter recalls. She managed so Dorothy could take violin and piano lessons—so that Ann, who’d sung and danced joyously from babyhood, could go to the Ned Wayburn School for training. “I think she hoped something would come of it, because she felt in her bones this was work I’d enjoy. And how right she was!”

Something came of it when the little girl was five. Through a friend, Mrs. Blyth heard that NBC was auditioning children for Madge Tucker’s Sunday Show. “Let’s go over and see if they’ll listen to you sing.” As Ann talks about it, the memories come clear—how she had to mount a big box to reach the mike, how she sang “Lazybones,” how they stood outside anxiously awaiting the verdict, how the man appeared smiling and said, “We’d like to have you on our program.” They kept her on it for seven years. Milton Cross was the announcer. Every time she hears his voice nowadays, she’s back there for a moment.

For Ann these were sunlit years. She had her mother. She had her Aunt Cis and Uncle Pat, like second parents. Each summer the family went to their Connecticut farm, away from the hot city, where she could romp as she pleased.

By the time she graduated from the grammar grades, her plans had taken serious shape. Along with the Sunday Show, she was working on Miss Tucker’s Saturday program which produced little plays. She wanted to be an actress. So it seemed advisable to transfer to the Professional Children’s School, where they were just as strict about your lessons but gave you time off when a job came along.

There Herman Shumlin, casting for Watch On The Rhine, found the dark-haired twelve-year-old with the blue eyes.

On opening night she wasn’t scared a bit. Not after all the rehearsals and try-outs, when Paul Lukas and Mady Christian—whose daughter Babette she played—and everyone else had been so wonderfully kind. It was simply the most exciting night of her life. With telegrams and adorable little corsages delivered backstage, so she felt like a real actress. With the warmth of the audience flooding across the footlights, so they knew they had a hit. With a midnight supper among family and friends at a small restaurant off Broadway, and by the time supper was over, the papers were out. Ann read them and wept. She won’t tell you, but the papers will, that Babette reaped a goodly share of the raves. “It meant so much for so many reasons,” she explains. “It meant that for the first time in years my mother wouldn’t have to work so hard.”

The play ran for eleven months on Broadway, and on tour for a year. Henry Koster, then with U-I, saw it in New York and again in Los Angeles. “The child,” he said, “is as enchanting as I remember her. I want a test.” To the Biltmore Theatre came a phone call from Mr. Koster, followed by a visit from the casting director. He told Ann she could choose her own scene for the test. At the studio a few days later, she did one of her favorites—the scene from Peg O’ My Heart in which Peg leaves her father. The powers-that-be seemed pleased. But Ann, not yet fourteen, was well trained in self-discipline and control. “What looks good to the eyes,” she commented sagely, “sometimes doesn’t come off at all on the screen.” Refusing to set her hopes too high, she returned to work and to the paycheck envelopes that turned up in the mail regularly with her school assignments. The tour took them to San Francisco, where U-I called them. “We’re sending a contract for your signature, to take effect as soon as the play closes.”

How did she feel? “I guess everyone dreams about being in pictures. I was no different. I loved the stage. But children’s parts, especially good ones, don’t come along too often, and pictures promised at least the chance of a steady income. So Mommy and I said some prayers and signed the contract. Once it was signed, we felt everything would work out for the best.”

It was a wrench to leave Aunt Cis, Uncle Pat and all their friends for a wondrous place called California where they didn’t know a soul. They continued to miss the family. That never changed. But new friends certainly helped. There was Donald O’Connor, with whom she made her first picture, Chip Off The Old Block—Donald the pro who gave her so many tips and such moral support. The sneak preview was shown way out in Glendale. It took forever to get there by streetcar and bus. Ann sat low in her seat and pulled on a handkerchief. Mommy liked it. “She probably realized I had a lot to learn, but there for the first time on the screen was her daughter. Her daughter made little impression on anyone else. Nobody recognized me outside. Nobody asked me for an autograph.”

Another early friend was Al Rockett, the trusted agent who guided her career from the start. He realized that, along with her sweetness, she had fire and spirit. In short, he believed in her as an actress and kept his eyes open for a chance to prove it. The chance came with Mildred Pierce the Joan Crawford starrer at Warners. “The part of the daughter is open,” said, Al. “She’s a bad character, and one of the, juiciest roles I’ve ever read. U-I will lend you. Whether Warners would take you is another story. It stands to reason they’d rather use someone under contract. But, I’ll do my best to talk them into a test.”

Mildred Pierce won her an Oscar nomination and a prominent spot on the Hollywood map. All horizons looked rosy. She started a second picture on loanout to Warners, called, curiously enough, Danger Signal. But Ann wasn’t superstitious them and isn’t now. Any link between the title and what followed was coincidental.

Some close friends had come visiting from the east. Though it was April and past the heavy-snow season, they decided to go to Arrowhead for the week end. Once in the mountains, they found a place called Snow Valley which showed enough snow to promise some fun. They rented a toboggan. The older folk, including Mrs. Blyth, stayed behind having coffee.

Ann was last man on the toboggan. First time they went down, it felt kind of bumpy. A doubt crossed her mind. “I don’t think it’s supposed to feel like this.” But the sun was shining, the kids were shouting, pulling the toboggan uphill again. Nobody realized how shallow the snow lay. Down they went for the second time, but fast. One of the bumps pitched Ann into the air and back against the hill. Pain stabbed through her. Instinctively she felt at her throat for the medal she’d been wearing, but the chain had snapped. Her hand went groping into the snow, found it, held it tight while she lay there, waiting for the pain to subside. For of course it would subside. It couldn’t be anything really serious. A pulled muscle maybe. Pulled muscles, she told herself, hurt very badly.

The others had been tossed off, too, but with less violence. They came running now. One of the boys helped her up and over to a tree stump. “Just let me sit here a minute. I’ll be all right.” But in a sitting position, the pain grew worse—so excruciating that it forced a sob to her throat, which she forced back. Because she had to prove to them and herself—and especially to her mother, unknowing down there in the ski shop—that this was nothing, that presently it would pass. How she managed remains inexplicable, but manage she did to walk down the hill and into the shop.

“What’s wrong?” asked her mother.

“Oh, we were bumped off the sled. No harm done, though.”

Nan Blyth took one look at her daughter’s paper-white face. Turning almost as white herself, she assumed quiet command of the situation. They had friends in San Bernardino. “You can rest there. Then, if you feel better, we’ll drive on home.” Again Ann walked to the car. But by the time they reach town, she couldn’t move and had to be carried into the house. There was no longer any possibility of pretense. All she could do was try to bear the pain. They got her to the hospital, where an intern, hearing that she had been able to walk, decided this must be a case of a strained back and taped her up. After which, on her mother’s insistence, X-rays were taken. A mass of quivering nerves now, Ann heard the doctor say: “Well, young lady, that tape will have to come off.”

She remembers flinching, she remembers his gentle “I’m sorry,” answering the mute plea in her uplifted eyes, she remembers how they began peeling the tape off—then she remembers nothing.

The X-rays showed a compressed fracture of the vertebrae. In a special bed that supported her back while her head and feet hung down, Ann lay stunned and incredulous, all the rosy future shadowed by dread, all her thoughts driven toward one she could hardly face—would she ever walk again? The physical discomfort was intense, but nothing compared to her emotional turmoil. She was little more than a child. Early hardship had been softened boy her mother’s care. She’d worked from the age of five, but at work she loved. Life, kind until then, now showed itself harsh. Lying there day after endless day, her head spun with the question all humans ask themselves when some seemingly senseless misfortune drops from the sky. Why should this happen to her? Why now, with everything in life going so well?

Each of us finds or fails to find the reply. Ann found it in her mother, who never left her side. Mrs. Blyth wrestled with her private anguish in private, resolved not to add its burden to Ann’s. Courage and cheer entered the room with her. Her belief in God was no reed to break under storm. Faith isn’t faith that doubts at the touch of affliction. What He sends one accepts, though one doesn’t understand the reasons. And the power of prayer is great. Through her mother, the seventeen-year-old gained new insight, new maturity, new spiritual strength.

In the end their prayers were answered. Ann would walk again, though not tomorrow nor next week. For four months, the doctors told her, she’d wear a cast, and a steel brace for eight more. She couldn’t go back to work for at least a year. But there’d be no permanent after-effects. Not only would she walk—eventually she’d swim, play golf, ride horseback again. To one of her age, a year seems longer than it is. But Ann was too grateful, too busy counting her blessings to lament on that score. Her head turned on the pillow, her hand sought her mother’s. “I’m the luckiest girl in the world,” she said.

Before she’d completely recovered, tragedy struck. During those months in the little apartment on Highland Avenue, while she nursed her daughter back to health, Nan Blyth began feeling ill. Not only did she keep the knowledge from Ann, but tried to dismiss it from her own mind, ascribing it to shock and strain. Once Ann was well, she’d be all right again too. But the time came when she could no longer dismiss it. One day they went out to San Bernardino for new X-rays of Ann’s back, which showed the fracture to be all but healed. At home again, Mrs. Blyth steeled herself to the task ahead—the task of dealing her child a bitter blow. What had to be done, she did. “Honey, I’ve seen the doctor. He says I need an operation.” The color drained from Ann’s face, her heart froze within her. “I’m going to be fine, dear. But I don’t want you here alone while I’m in the hospital. So I think we’d better phone your auntie and uncle and see if they can come out to stay with you.”

After the phone call, after Aunt Cis and Uncle Pat had promised to come right out, Nan Blyth’s face dropped into her hands. For the first time in her life, Ann saw her weep. With the world crashing around her, with the nightmare sense that none of this could be happening, she cradled her mother in her arms.

Through the weeks that followed they hoped against desperate hope. But the operation came too late. Ann’s beloved mother died.

Such was Ann’s grief that she cannot talk of these things today. In her first desolation, even prayer didn’t help. The same heartbroken cry went up. “Why, why? Why should it happen to her, so good, so dear, so needed?” But she was fortunate in her dear aunt and uncle. No two people could have loved her mother better. To them, her loss meant less only than to Ann. Yet, once the first shock lay behind them, they refused to stand by, watching her shatter herself against the inevitable. Out of their larger experience, out of their clear good judgment and honesty they spoke. “Ann, we can go just so far with you in your grief. You must find your own way. Your mother isn’t lost to you if you seek her through prayer and faith and the knowledge that she’s still with you forever and ever. But you cannot find her if you nurse a sense of betrayal.”

It couldn’t happen overnight. But little by little Ann did find her way through the blackness back to the gates of prayer, where she drew close to her mother’s spirit again. Again the beloved voice sounded in her ears. “God in His wisdom has a reason for what He does, and He always knows best.” Why it was best for her mother to be taken, shell never understand. But she understands that it’s not for her to question. As a child of faith, she need only accept His word.

She’ll never forget how Aunt Cis and Uncle Pat left their farm and all their ties in the east to answer her need, to give her solace and support through the dark days, to make a home for her here, warm and sunny as themselves. They found a little house in the valley—Ann’s first house with her first bedroom to herself—and none of your Murphy beds, but a real one.

When she was well enough, she returned to U-I and life began to resume its normal round. Her career throve on loan-outs. Goldwyn borrowed her for Our Very Own, MGM for The Great Caruso. Even Lanza’s brilliance failed to dim Missy Blyth’s. Who that ever saw her will forget the lovely little figure dancing and singing “The Loveliest Night Of The Year?” Certainly not Leo, the astute Lion, who from then on made a habit of borrowing her—for All The Brothers Were Valiant, for Rose Marie and Student Prince. Last November, her U-I contract up, she signed with MGM, where she’s just finished Kismet, first of her pictures under the new contract.

Meantime, Hollywood was playing a game called Let’s Marry Ann Off. To be objective, she wasn’t its only victim. For her name you can substitute Terry or Rock or Tab, since it’s a game played with all eligibles. Ann didn’t care for it. Speaking of the period when she was being tagged, her soft voice takes on an edge of firmness. “This is a phase of your life—even if you’re in pictures—that’s quite private and special. Not that you’re unwilling to share a certain amount, but only so much. It took me a little while to get used to these stories which I knew were untrue both about myself and others—and in many cases, unfair. Of course I went to parties and dances and had wonderful fun. It’s the natural way of youth all over the world. Yet in Hollywood some people seem to believe that girls and boys can’t go out without marriage in mind. They seem to urge it on you. But it was my life, and I felt no sense of urgency. When I fell in love, I wanted to marry. Until then I had no intention of marrying, whatever anyone wrote.”

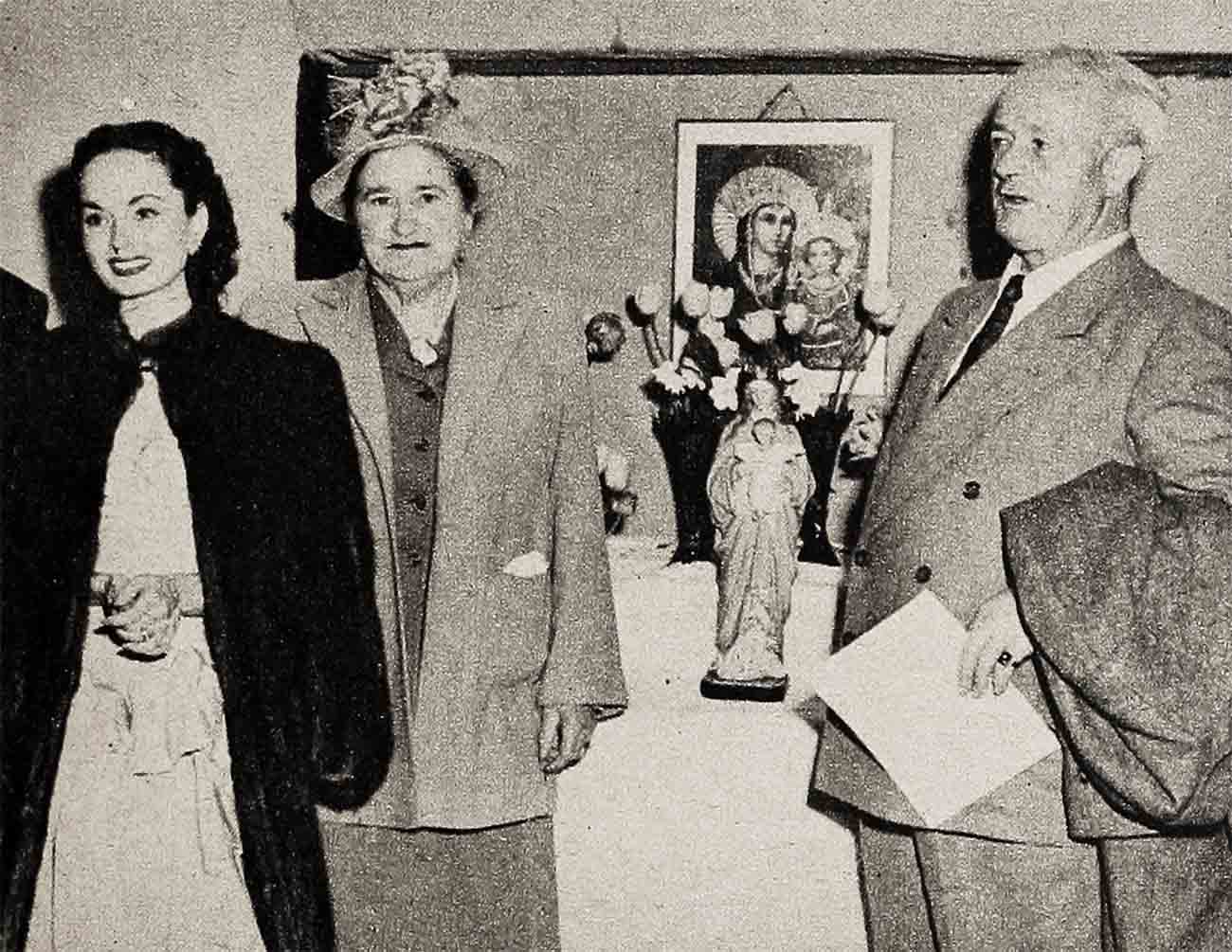

It’s been reported that Ann met Jim|| through Dennis Day. Not so. Five years ago during the holiday season she’d asked some friends to visit. They were also friends of Dr. James McNulty and thought these two might enjoy knowing each other. “Perhaps he and his mother and dad would like to come over,” Ann suggested. So it was in her own home that she met him first and remembers that she loved his face at once. “Such a kind face, so warm and happy. And I loved the sweetness of his manner to his parents. I can’t describe it but, if you knew him, you’d understand its quality. He had it then, he has it now, he’ll always have it.”

A week later he phoned. Would she care to go to the christening of Dennie’s new baby! She’s found out since that he asked her with some misgivings. Despite his brother’s place in show business, it was a business foreign to the young physician. They were reminiscing about it last Father’s Day. “I liked it,” said Jim, “that you seemed to have such a good time, just playing and singing and talking. I didn’t feel that you had to be entertained. I began hoping it wasn’t true what they said, that movie stars live in a different world.”

Through the next two years they dated on and off—went dancing when they could, since they both loved dancing, or just to a movie. But Jim was busy establishing his practice, while Ann flew off to England on a picture commitment and to Hawaii and Alaska to entertain the troops. Therefore long periods elapsed when they didn’t see each other at all, When they did, it was on the same basis of friendship.

Till a summer’s day in 1952. Friends invited them down to Balboa for some deep-sea fishing. Their friends described the excitement of latching onto an albacore. But before day’s end, something more exciting happened. Ann discovered that she was deeply, truly and beyond any shadow of a doubt, in love.

Aunt Cis had awakened her at 3:30. Jim came knocking at 4. They took along a picnic lunch of sandwiches and fried chicken. Out on the boat it was wonderful, the sky so tranquil, the air so sun-drenched, the hours with Jim beside her so perfect. Why the revelation should have come that day rather than another is one of love’s mysteries. Ann only knows that come it did, with some new and poignant sweetness stirring between them as their eyes met, quickening her pulses. On the way home Jim held her hand. Both were rather silent, though Ann’s frank to admit she kept hoping the man would speak up. He didn’t. Not in words, anyway. But for the first time he kissed her good night. With a hug. It was enough, she told her joyously beating heart. The words could wait.

Not until almost Christmas time did Jim venture to say them, and then only with a spirited assist from his mother. At a family party his eye caught a pretty necklace worn by one of the guests, and his thoughts were on a Christmas gift for Ann. “Mom,” he asked, “d’you think she’d like something like that?”

Mrs. McNulty’s a woman who minds her own business but this was too much and she gave it to him straight in her rich Irish brogue. “Now, Jim, why don’t you stop all this foolin’ around an’ give the girl a ring?”

The slow smile gathered, yet left his face grave. “Suppose she doesn’t want it?”

His mother eyed the son whom she once called the tenderest of her children. “If I were in your boots, lad,” she said gently, “I’d take the chance.”

He carried the ring in his pocket for a week, still incapable of shaping the question that might bring him high happiness or the end of hope. On the 18th he helped Ann and her folks trim the tree—always an intimate family ritual. Maybe the fact that he was drawn into it lent him heart. The hour grew late. He took leave of Aunt Cis and Uncle Pat. Ann walked him to the door. They made a date for a couple of evenings later. He kissed her good night, started down the path, paused and turned back, reaching into his pocket. “I have something for you, Ann. Will you wear it for me?”

The box was blue, the diamond beautiful, the moment more so, as she threw her arms around him and whispered, “Oh, Jim!”

The rest of the story’s been too well and recently covered for re-telling here. Ann will carry with her forever the memory of her wedding day in June. The honor of having His Eminence, Cardinal McIntyre, marry them. The good feel of dear Uncle Pat’s arm as they went down the aisle. The smile on Jim’s face at the altar as he stepped up to claim her. “Such a sweet smile,” she recalls. “So sweet that apparently everyone noticed it.”

With the birth of Timothy Patrick a year later—her cup brimmed over.

Now they’re waiting for the new baby—the new link in their precious little family circle. Ask her how many links they hope for, and her head goes back in laughter delightful as Tim’s. “Who am I to tell the dear Lord His business? As many as in His wisdom He chooses to send.”

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITLIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955