Troy Donahue Life Stor

FINAL INSTALLMENT: (Ed. Note: In Part 1 of Troy Donahue’s life story, “Here’s My Heart, Take It At Your Own Risk,” which Photoplay presented last month, author Kirtley Baskette described Troy’s boyhood—happy until his fathers death. Rebelling against the loss of a parent who had been his best friend, the boy ran wild with a wild crowd, got out of hand and forced his mother to drastic steps. W hat the steps were—and what Troy made of his life—is told below.)

Dede Johnson desperately called around town begging cooperation from other parents on holding down the hi-jinks. Nobody seemed to care. At school Troy goofed off more and more. In algebra class he faced a test knowing nothing. He handed in a blank paper. “What’s this?” asked his teacher.

“Invisible ink,” cracked Troy. He was bounced from class and flunked. To his harassed mother, all this spelled out one thing—military school. She couldn’t handle him and he couldn’t seem to discipline himself. But she didn’t pack him off, reform school style. They talked it over. In the clutch, an appeal to reason usually worked with Troy and still does. On location in Connecticut for “Parrish.” Troy turned up too many mornings with obviously weak homework. His unprepared fumblings held up shooting and. with reason, annoyed Karl Malden and Claudette Colbert. Delmer Daves took Troy aside and let him have it. “You’re hurting yourself and humiliating me with these professionals,” be pointed out. “If it happens again, we’ll pack up and go home.”

“Del,” promised Troy soberly. “I give you my word it will never happen again.” And it didn’t.

Back then, going to New York Military Academy made sense to Troy. “I could see myself going right down the drain in Bay-port,” he says. “I was lazy, wild, spoiled and off the track. I knew I needed straightening out with formal discipline. But I wouldn’t say I went up there laughing and singing. I knew that what was ahead for me was no bed of roses.”

He was heading for a top-rated military prep school at Cornwall-on-Hudson, right up the river from the U. S. Military Academy at West Point. In fact, uniforms were identical with those at the Point, classes as tough, hazing as rugged. Although he entered as a junior, Troy led the dog’s life of the first-year men. He shuffled around double-time, “braced” for upper classmen, shined their shoes, slept on boards and recited ignominious slurs at himself. His blond curls were clipped and with them his teenage cockiness. “I was rough on him and at first I imagine he hated my guts,” says his first year roommate, Owen Orr, now a pal in Hollywood. “But ‘Johnnie’ turned into a first rate cadet and a helluva guy—after he settled down.”

The first month in school, Dede Johnson paid out $300 in bills Troy piled up—for souvenir necklaces, bracelets and charms he sent the girls back home and for flowers for other girls he slipped off to see in nearby Newburgh. He also broke the school record for piling up extra-duty tours as punishment for various defections. “I hated it at first, but it was what I needed,” he allows. “Gradually I learned that rebelling was defeat. The whole point of the school was to make kids like myself realize that life is competition, that we were competing with ourselves, and that if you’re to win anything, your first battle is right inside you.”

Before long Troy liked military life so well he thought of going on to West Point and making Army his career. Actually, his marks never warranted that; now he paid for the time he had wasted in Bayport High. But athletically and militarily both. he qualified. He made cadet lieutenant. He made the basketball and football teams, and broke all school records in the high jump, soaring 6 feet 6 inches. Ironically, that triumph put West Point out of the question.

One day some joker dropped a brick in the jumping pit and Troy came down on it with one knee, knocking it out of joint and tearing the cartilage. After that he knew he’d never pass the physical for West Point. Later, when he put in for his military service, the doctor inspected Troy’s hum knee. “Step out of line, son,” he said. “No point in going on. You’re 4-F.”

Knocked out of sports by a brickbat, Troy concentrated on writing and acting. Nobody could keep him from scribbling. but always before there had seemed to he some deep-seated conspiracy to keep him back in the shadows of any school or church play. He was so tall and gangling that he wound up as an Indian or an Arab. “The nice little kids with the best marks were always Miles Standish or Jesus,” he recalls. It was frustrating. Now, in the most unlikely place, he got his chance.

His class in Theater Arts put on one big school show each year. Troy was already writing for both school papers and had wound up editor of “The Shield,” so his teacher invited him to see what he could whip up for the show. Troy came through with one called “Yea, Furlough!” a wacky takeoff on cadet life. He wrote, produced and directed it. Also—naturally—he gave himself a fat part.

“It was really a darned good show,” says Owen Orr, who played in it too. “Even the flint-faced instructors howled.” After that hit, Troy thought he saw his future come into focus. He’d be one of two things, a writer or an actor—for sure. But first he had to graduate. He made it after one last narrow squeak with disaster. As usual, it involved a girl.

Troy had met her at the one formal hop they held each year where. romantically, all the cadets and their dates walked through a giant replica of the school ring. She walked through with somebody else, but a thing like that never bothered Troy. He started writing, and at Easter vacation knew he just had to go down to New Jersey and see her. He talked a pal into going along. Both wrote their mothers that they were visiting each other. The plan seemed foolproof.

Unfortunately, Dede called where Troy was supposed to he visiting. “I thought my boy was staying with you!” gasped the other mother. The next call Dede made, anxiously, was to the police. After that, Troy’s sentimental journey turned into a Hitchcock thriller. Cops chased them on trains and buses, while the fugitives dodged and double-tracked. They were never caught, but finally scurried home to safety—after they’d seen the girl. Luckily, the authorities at NYMA didn’t hear about t his.

Troy graduated in June of 1954, and now felt ready to tackle the theater. But his mother, while sympathetic to his ambitions and convinced he had talent, decreed that college came first. Troy couldn’t see studying what he’d never use, and fought the decision. Now he admits, “I made a mistake. I wish I’d listened and got a better education.” But at that time he was so confused that he decided to shake himself down with hard work all summer and make the Big Decision come fail. If it came out what he thought, a stake would be handy to have.

Until then. the only thing Troy had ever tackled even resembling a self-supporting job was as counsellor at Camp Tabat on Long Island. Eve went there and Troy, between terms at the Academy, marched her and the rest of his kids around like soldiers. But that was really fun. This time he tackled a killer—on a crew building a parkway in New Jersey. He looked like a man, so they gave him a man’s job—dredge work and hoisting heavy iron pipes.

Troy collected $55 a week and earned every cent. He worked hip-deep in the muck of steaming swamps, the only kid in a crew of husky Norwegians and Poles—who couldn’t speak English. He lived on the job, flopped into his bunk at night so tired he slept through the ear-splitting din of the night shift. Near summer’s end, he almost buried the foreman alive in a load of sand and got fired. But by then—although he’d saved only $50—he knew what he had to do, and Dede couldn’t talk him out of it. With his $50 and two bags of clothes, he went to New York and checked in at the Y.M.C.A.

Troy couldn’t have told you just what he was after. Not then. The closest definition would be his manhood. There comes a time when every boy has to make the break and test himself. Troy Donahue did it early—maybe too early. He didn’t have to. He had a comfortable home where he was welcome to linger, even if he didn’t take up a free ticket to college. He knew his mother would even stake him for this precocious career Hing if he asked, even though she couldn’t exactly cheer him on. But that would have killed the whole idea. He had to discover his own values, capacities and hungers wide open, with no strings attached.

To support himself, Troy found a job as a messenger boy with Sound Masters, Inc.. a film company his dad had founded. Acting was on his mind, of course, but Troy wasn’t silly enough to haunt Broadway agents hunting a job on the strength of a military academy show. He went to Ezra Stone, an old friend of the family, and asked to join his Theatre Wing Workshop. At the same time he signed for some night extension courses in journalism at Columbia University. One or the other, he thought, would surely show him the way. Neither did with a big, green light.

Troy batted out some sketches and sent them to the New Yorker. They came back with encouraging notes, but back just the same. At the workshop he felt he was accomplishing something (It’s the only serious acting instruction Troy Donahue has ever had.), but the others there seemed so much more advanced, so confident and talented. “They were all in it a little too deep for me,” as Troy puts it. “I felt like an outsider.”

Self-conscious with the arty set, and suddenly feeling very young, Troy was lonely. He couldn’t live decently on his messenger boy salary. He rattled around a dozen cheap hotel rooms and dingy apartments that year. “Walk-ups, walk-ins, walk arounds, cold waters, cold floors—every- thing,” he remembers. “Six times I got kicked out for not paying my rent.” Although Dede Johnson had sold the big Bayport place and moved with Eve to a nice apartment on Riverside Drive, Troy went there only to visit—and get an occasional square meal. But often his belly felt like an empty sack full of gnawing mice. He discovered a cheap way to chase them out.

“I used to get up in the morning, walk to the corner and buy a ten cent hot dog,” recalls Troy. “Ever eat a hot dog with mustard for breakfast? It makes you so sick you don’t want to see food the rest of the day.”

For diversion there were always girls, but not the kind of girls Troy had known on Long Island. He picked them up on the Street, in subways and in cheap cafes. Usually they left a flat taste afterwards. Then suddenly one came along who left Troy with worse than that—a badly bruised heart.

He met the girl with the mink coat at one of the few respectable uptown parties he took in that year. He had never known anyone like her before. He fell hopelessly in love and for four months lived in a daze of adoration, a devoted slave and putty in her hands. Then one day she tossed him aside like a squeezed lemon. “I guess I walked in the door at the wrong moment,” he says ruefully, thinking about it. “When I walked out I didn’t know what to do. It was the first time I had ever been really hurt. And it came at a bad time for me. For a while I didn’t care about anything, I didn’t want to do anything. The world turned black.”

About the same time he suffered another blow. At Sound Masters he had finally worked up to film cutter. Ironically, the boost cost him his job. He was too young to join the union, and the other cutters complained. “Sorry, Merle,” said his boss, “but you know how it is. I guess we’ll have to let you go.”

The one-two punch took the steam out of New York for Troy. Suddenly he wanted , to get out of town. He knew he hadn’t found what he was looking for, whatever that was, but he also knew he’d gone through a lot of growing up. Dede still talked college and Troy still considered it —vaguely—but he was impatient to get hold of something in a hurry. He thought of Hollywood—and had to grin remembering a remark Eve had made the first time she looked at a copy of Photoplay: “Some day you’ll have your picture in this.” Eve always thought he could do anything. Maybe it was his fault; when she was just a little girl he used to tell her, “I’m really Samson. I’m the strongest man in the world and whatever I want to do, I can.” Silly kid, she believed it.

The only person Troy knew in Hollywood was Darrell Brady, a man his dad had once helped get a job with Paramount News. Brady now ran his own commercial film company on the Coast. Troy wrote him a letter, but an answer didn’t come right away. Meanwhile he found a job on a surveyor’s gang back on Long Island, near Sayville. Sayville had a playhouse. At nights he fooled around there. His best job was a supporting part in “Stalag 17,” but it was hardly a ticket to Hollywood. Success wasn’t to be that easy.

The letter came at last saying what Troy hoped it would: “Come on out. You can stay with us and I’ll give you a job.” To make things even easier, Darrell Brady said he needed a new car which Troy could pick up for him more cheaply in the East. Why not drive it out and save plane fare? Troy showed the letter to Dede and Eve. At the time, Eve had a crush on about every star in Hollywood. “Take me, too,” she begged. Outnumbered, Dede Johnson gave in. Troy and his kid sis drove out of New York in a new Chevy convertible in February of 1956, “feeling like pioneers.” Troy was nineteen and Eve twelve; neither had ever crossed the country before.

Troy was so impatient to get going that he barreled the new car across Route 66 in five days, driving ten hours a day with his foot pressed to the floorboard. “The only time Troy took his mind off California was in Albuquerque,” Eve recalls. “He must have had a good time because he got back to the hotel room at four o’clock in the morning.”

Troy and Eve checked in at the Bradys’ house in Calabasas, in the San Fernando Valley just over the mountains from Malibu Beach. Troy went to work at Commercial Film Industries in Hollywood, cutting film. He knew the work and liked it okay. He knew Darrell Brady would teach him the business and see that he got going. But that wasn’t what he was after, and Darrell Brady knew it, too. He knew Troy wanted to act or write. Brady felt it his duty to set him straight.

“Both are very long shots,” he warned. “Nothing’s more uncertain and full of heartbreaks.”

“I know,” Troy replied.

But to him a big dream was the essence of California. The very sunshine gilded the place with promise. From the minute he arrived he felt anything could happen. Young people with fresh ideas were scoring all around him. “It seemed crazy,” he admits, “but I believed I could do it, too.”

Troy Donahue is a sensuous person in that he doesn’t always figure—more often he feels. At night he used to borrow the Bradys’ car, roll into town and stand around Sunset and Vine, looking at people who passed, listening to what they said. On weekends he went out to Beverly Hills and the Strip, around the studio districts, all alone, with his antennae spread wide. “I wanted to get the feel of this place. I didn’t have any plan. I guess I wanted to be discovered,” he confesses. And that’s exactly what happened.

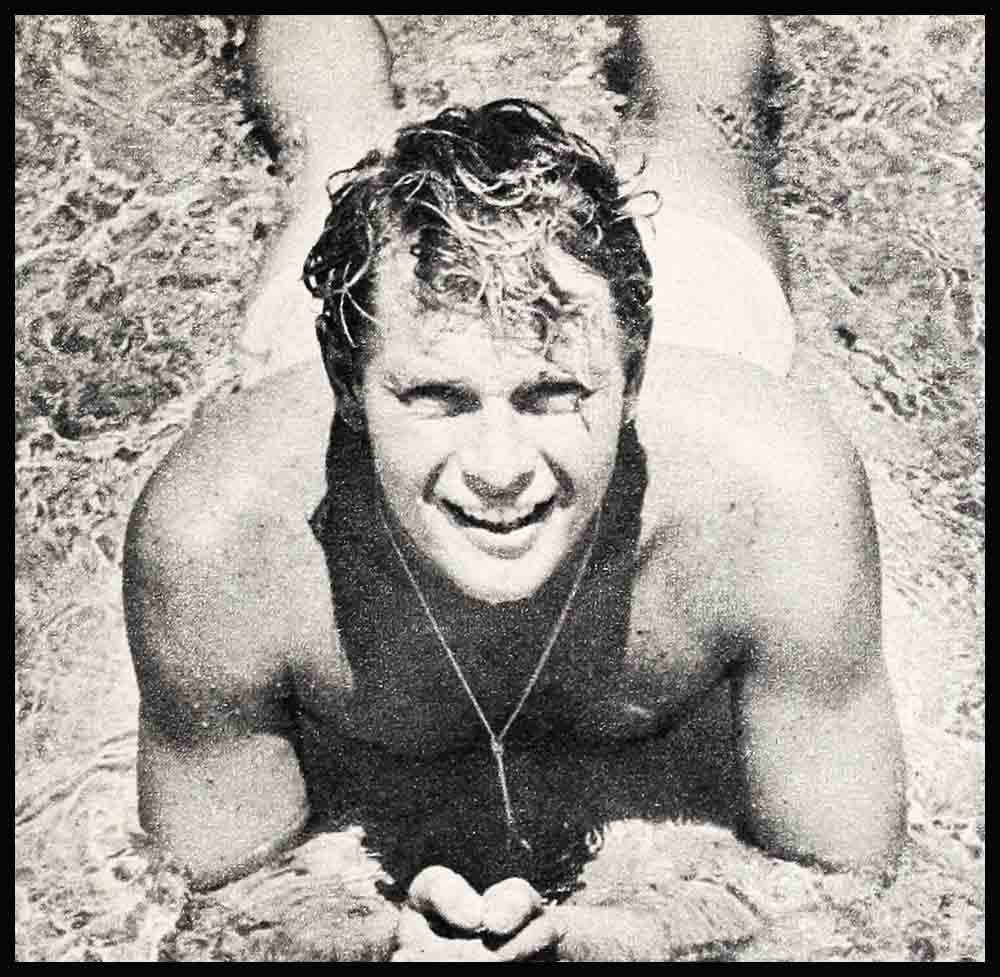

Dede Johnson had come out and rented a house in Malibu, but she didn’t like the climate and soon took Eve with her back to New York. Troy found a garage apartment nearby and a used MG for $700, on time. After work he liked to drive through Malibu Canyon to a cafe called The Golden Pheasant in the Valley. One evening about 8 o’clock he was sipping beer at the bar. He didn’t sit at a table because he thought he looked awful. He wore levis and a heavy jacket over a T-shirt. His face was burned brown, his hair sun-bleached and wilder than usual. “I could have been a beachcomber or a truck driver,” says Troy. “Turned out I was rigged perfectly for a young actor.”

At least two people thought so. Troy felt their eyes on him and finally they came over. One was James Sheldon, a TV director; the other William Asher, a producer at Columbia Studios.

“Done any acting?” asked one.

“A little.”

“Are you interested?”

“Very much.” And Troy told them his story. Jim Sheldon brought in a television script from his car. He explained that John Erickson already had the part, but if Troy would read it and come see him next morning—well. they might have something to go on. “Come see me, too,” invited Bill Asher. Troy stayed up most of the night studying the script. Next day he had his moment of truth when he read for them both. “I was terrible,” says Troy.

But they liked him, as most people do who meet Troy Donahue. “I’ll keep an eye out for you,” promised Jim Sheldon. “You’re a good-looking kid and you can learn to act,” encouraged Bill Asher. He took him to Benno Schneider, Columbia’s head drama coach. Benno set up a screen test for the next Monday. By Monday Troy was in the hospital.

He had meant to take it easy that week- end. But a friend he’d met at the beach dropped by. “Come on, let’s get polluted!” he commanded. “I’ve just passed the Bar exam. Call me Attorney, son.” Troy always has a rough time saying “No,” especially to a good time. And didn’t he have a screen test in the bag to celebrate? “I’m with you,” he said.

They cut out for the Golden Pheasant. About one o’clock, after too many beers, Troy was screeching the MG around Malibu Canyon’s curves, headed for home, when he hit a wet spot in the road. The light sports car skittered over a cliff and smashed against a tree forty feet down the canyon wall. On the way Troy’s friend bounced out and landed on his feet without a scratch. Troy doesn’t remember anything until the next afternoon. But his pal told him he climbed out of the wreckage cussing a blue streak, grabbed the MG’s door and hurled it the rest of the way down the cliff. Then he stalked up the side, down the road and out on the highway, yelling bloody murder. That’s how he looked, too. “They say my face was just two blue eyes staring out of a bucket of red paint,” says Troy.

At Santa Monica emergency hospital the doctor who patched him up ticked off the damage: Two cracked knees, brain concussion, bruised spinal cord, crushed kidney, missing tooth, severe shock. He took forty stitches in Troy’s scalp, ten in his nose. When Troy came to at last, the doc told him, “Son, God must be saving you for something. By rights you ought to be dead.”

He lay in the hospital a month. Dede flew out to help, and then went back to New York. Jim Sheldon and Bill Asher told him not to worry—they could resume where they left off when his shaved hair grew back. still banged up, and his car wrecked, the road back seemed long and dismal. One day, when he was feeling as low as a snake in a swamp, Troy thought of a peppy girl he’d known back in New York. Joyce Branning had played in commercials at Sound Masters and then. he remembered, gone on to Hollywood. There were about fifty Brannings in the phone book, but he got her on the third try. girls don’t forget Troy. “Merle!” she cried. “Where in the world are you?” He told her where and why. “Don’t move,” ordered Joyce. “Two utterly fascinating girls are coming right out to see you.”

Joyce Branning was kidding, but not too much. She later married a Vanderbilt. The other charmer was Fran Bennett, a blond, cameo-faced rich girl from San Antonio, Texas. Just out of fashionable Finch School in New York, Fran was having fun with a fling as an actress. Fran’s the type of supercharged Dixie belle who thinks and talks a mile a minute, likes nothing better than a Cause. She took over Troy’s. Like General Forrest, Fran believed in getting anywhere “fustest with the mostest.” To her, Troy was the mostest. The fustest thing was to get him a good agent. Hers was Henry Willson.

“People say I’d make a better agent than an actress,” Fran admits cheerfully. “But I knew what Henry could do with Troy. He was just his cup of tea.” Willson has cracked open careers for more raw young stags than any man in Hollywood—Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter, to name a couple. Trouble was, he had a waiting list a mile long. But Fran can talk up a storm.

A few days later she called Troy. “Run like hell to Henry Willson’s office and meet me there,” she ordered. “Hurry—he’s leaving for Hawaii right now.” Troy borrowed a car and made it just in time to catch Willson in the hail, lugging his bags for the airport. After a few fast questions and keen looks, Willson said, “Go out to Universal. Say I sent you. ‘Rock Pretty Baby’ is already cast, but they’ll know you should have been in it. Bet you get a test anyway.” To Fran Bennett he made a circle of his thumb and forefinger. “You’re right,” he said, and vanished.

“I think you’re in,” said Fran to Troy.

She was right. Troy got his first screen test at U-I and it was A-Okay. Back from Hawaii, Henry Willson took him over. A few days later Troy called Henry’s office, but the line was busy. Henry was calling, too—Troy’s number. Finally they connected. “I just wanted to congratulate you on your new U-I contract,” he told Troy. Three days later, Willson rolled in the studio gate. “Has Merle Johnson come in?”

The name game

“Nope,” said the guard. “She hasn’t been around.”

“Oh-oh,” muttered Henry, “I forgot something.” That week he took Troy to a birthday party for Lana Turner. As a game Henry suggested. “Let’s think up a new name for Merle.” Ideas flew thick and fast. Everyone knows about Henry Willson’s blunt male-tags: Rock, Tab, Lance, etc. How about “Crash Helmet,” “Mack Truck,” “Pebble Beach,” they fooled. Not amused. Willson went into a Creative trance. “Very handsome,” he mused. “Who was so good looking?—Paris! Paris— Helen of Troy—that’s it. ‘Troy’—Troy-uh- Donahue.” They christened him with a squirt of fizz-water. By now Troy has almost forgotten that he ever was Merle Johnson. He likes his movie name; even Dede and Eve use it now.

But “Troy Donahue” started very few hearts fluttering in the eighteen months he lasted at Universal—except in certain limited circles. He ducked in and out of sixteen pictures, but you had to look fast to see him. He made $125 a week and spent every cent of it. He mortgaged the checks ahead for a Porsche sports job, moved around from one bachelor apartment to another. With too much time on his hands, he mixed in with party boys and party girls. He had some shabby romances and one or two that shook him a little. Sometimes he drank too much. But it was the Porsche that got him in trouble.

In one stretch he collected four tickets—for speeding and running red lights. Carelessly, he let them pile up until the police nabbed him on a bench warrant. Troy figured he was in for a stiff fine; he had $200 saved up to pay it. But the judge thought it was time to make an example of these wild young Hollywood actors.

“Fifteen days in the county jail.”

Troy served them. He’s never forgotten it. “Frankly,” he says, “it scared the living daylights out of me.”

All this Troy appraises as “just a sample of what can happen to someone like me, all souped up and no place to go. Keep me busy and I work hard. idle me down and I have the instincts of a beachcomber.” For a while he almost was one.

Because suddenly the party was over. Universal cut production back sharply, keeping only their stars. Troy Donahue was out. He was also stone broke. Oddly, he wasn’t a bit discouraged. “I’d found out what it was all about,” he explains. “You pay to learn. That was my shakedown cruise. I didn’t feel like a loser. Funny, but I had more faith in myself than ever. I knew something good was ahead for me.” Even at twenty, it took some pretty rosy glasses to see that.

Troy was so broke he couldn’t afford a place to live. His mother and Eve had moved to Beverly Hills, but Troy felt the same way he did in New York. Going home was defeat. For a while he slept in his car. Sometimes a friend gave him a bed. “I managed to find a few nice places to sleep,” Troy grins. “Some very comfortable, too.” Eating was tougher. Once when the mice gnawed inside, he cleaned up around Hamburger Hamlet for free burgers.

Troy Donahue thinks the rock bottom jolt was good for him. “When you’re hungry,” he says, “you don’t muff the next chance.” For a while they were just TV bits. Then Ross Hunter called him back to U-I for “Imitation of Life.” It wasn’t a part Troy or any other young actor would deliberately pick. Pretty ugly. in fact. He had to kick Susan Kohner in the gutter. when he discovered she was a Negress. But it showed Troy off at last and gave Henry Willson something to sell. He thought he knew just the spot.

At Warner Brothers, three pictures were ready to cast, and all three begged for someone like Troy Donahue. They were “A Summer Place,” “Parrish” and “Splendor in the Grass.” Henry Willson moved into the opening like a scatback. Troy tested for “A Summer Place.”

“There were eight other good actors after the job,” reports Delmer Daves, boss of that show. “But the sensitive. groping boy we were after was Troy Donahue. right out of life. He didn’t have to act.

“The hardest thing about ‘A Summer Place’ was believing it was happening to me,” Troy recalls. “At U-I I’d never got anywhere near Sandra Dee. Now, incredibly, I spent day after day doing nothing but kissing her. But,” he grins, “she seemed to like it.”

Apparently, so did everyone else. At last Troy had what he’d needed—a romantic lead in a smash picture and a fat long contract.

Warren Beatty beat Troy out of “Splendor in the Grass,” but Donahue followed up with “Parrish” and “Susan Slade.” Along the way, ABC-TV executives told Warners, “Get us a show with Troy Donahue and we’ll buy it.” They cooked up “SurfSide Six,” and Troy has been running between movie and TV sets ever since—among other places. In the past two years he has crossed the country seventy-five times—on locations, personal appearances and television jobs.

What has all this success done to “the boy” who left home at seventeen hunting something, he wasn’t sure what, but wide open to the world?

“Nothing at all,” answers Fran Bennett, who knew Troy when he was almost that. Never in love with Troy, Fran is safely married, a mother, and lives in San Francisco. Recently she came back to Hollywood on a visit with her husband and baby. “Stay with me,” invited Troy.

“He hasn’t changed in any respect one bit since I met him.” Fran swears. “There’s no one I’m more at ease with. I can’t believe it.”

Owen Orr, Troy’s old roommate at military school, backs her up. Recently Troy arranged a reading for Owen at Warners and introduced him to Henry Willson. Now he’s a client and on his way. “Troy’s just like he was at school,” says Orr. “The same guy.”

That’s not quite true and no one knows it better than Troy himself. “I still have all my faults,” he points out. “I’m a financial idiot. I’m disorganized. I put things off. Basically I’m lazy. I drive too fast. I like sports too much, fun too much, nice things too much. But I think some of the rough edges are rubbed off at last. I’ve matured in several ways. I’m serious about my work and luckily I love it. To me the whole thing is a big, wonderful ball. I can’t wait for each day.”

Particularly, Troy likes action. “I’m a frustrated stunt man.” he confesses. Making “Susan Slade” on the rocky Monterey coast, he was supposed to ride a horse off a cliff into the sea to rescue Connie Stevens. They hired a double, of course, but when the cameras rolled, it was Troy who rode out from behind a rock aboard the horse. He’d figured a way to shorten one stirrup and jet out of the saddle in mid-air. But he could have got himself killed. If he avoids that fate, Troy thinks, “I might be a fair enough actor someday, but I’ve got a long way to go.” Eventually he plans to produce and, especially, write. That kick has never left him.

As for another—girls: “Well, I’ve simmered down there,” says Donahue. If you read about the explosive ending of Troy’s engagement to Lili Kardell (see Lili’s own story of how Troy beat her up in the November Photoplay), you know he hasn’t simmered down all the way.

Yet Lili was aware of Troy’s temper even while she loved him deeply and expected to be the girl he’d finally marry.

“Troy has his faults,” she admitted in that earlier, happier time. “He has to learn the hard way; you can’t tell him anything. He has a temper that flares up, and fizzles out as fast. We’ve had our fights. If something about you bothers him, though, he lets you know right away—and that’s good. He’ll never get ulcers. But he can’t be clever about himself. He has a fine mind. but he isn’t using it fully. There are a lot of things he can do if he ever buckles down to them.

“With women, Troy likes to be boss,” continued Lili. “He’s the protector, and that’s as it should be. Sometimes he’s thoughtless, but he’s sympathetic and kind, too. Troy needs a little of everything in a woman—sister, mother, sweetheart. He needs to be needed, too, by somebody. He’s possessive. At the same time he doesn’t like to be possessed. He can’t be tied down or taken over. He has to have a woman who understands that, or else he’ll rebel. But Troy wants a deep relationship with a woman. and he’s found he can’t have that with several. I think he’ll make a wonderful husband if he isn’t forced.”

That was the pre-disillusion appraisal of the girl who probably knew him better than any other of his flames. As of now, nobody can make a bet on if, when or who Troy Donahue may or may not marry.

But when and if Troy ever has ten years of marriage behind him. or twenty, nobody expects him to be too different than he is today, in one basic respect. If he winds up grizzled and full of success in Hollywood, as Clark Gable did, Troy will never play life by the rule book. cautious, cagey and safe. The way he’s made, he can never close the door.

“The tragedy of the closed people,” Hoyt Brecker also pointed out in “Susan Slade,” “is that they’re closed to the joys, too. So they live only a half-life.”

When Delmer Daves handed Troy that line to read, he had just a little trouble. “How can anyone live a half-life?” Troy wanted to know. “That doesn’t make sense to me.”

“It wouldn’t to you, Troy,” grinned Daves, who had a bead on his boy by then. “But go ahead and read it like you meant it. You’re only acting.”

—KIRTLEY BASKETTE

Troy’s in “SurfSide 6,” ABC-TV, Mon., 9 P.M. EST and “Susan Slade,” Warners.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1962

vorbelutr ioperbir

17 Temmuz 2023Attractive element of content. I just stumbled upon your site and in accession capital to say that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your weblog posts. Anyway I’ll be subscribing in your augment or even I fulfillment you get right of entry to consistently rapidly.