Beauty And The Beast—Audrey Hepburn

They’d had a wonderful week together. But now it was Sunday night and the week was over and they stood near the car, saying their good-byes.

Normally, Audrey Hepburn would have hated to see Mel Ferrer go away like this. But she knew that he had to leave her and return to Hollywood for good reason—to put the finishing touches on Green Mansions, a picture he’d directed, an important mark in his career.

Besides, Audrey knew, location work on her new picture, The Unforgiven, would be finished in less than a month and she would then be able to leave the village of Durango and be with her husband again.

And so she didn’t mind—not even as they held one another now, there in the heavy Mexican moonlight, and said good-bye, and kissed.

“Señor,” a voice called out, suddenly, from behind them, in the middle of their kiss.

It was Pablo, the chauffeur, rushing out from the pink adobe bungalow, carrying the last of Mel’s baggage.

“I told the pilot that we will definitely be there at ten o’clock,” the big, friendly voice boomed on, “—and it is nearly that time now. We must go.”

As he loaded the baggage into the trunk of the car, Mel and Audrey kissed once more.

Then, minutes later, the car began to pull away, jauntily, over the narrow, bumpy road.

Audrey waved.

“I’ll see you soon, my darling,” she called out.

And as she did,a cloud high above her began to settle under the moon.

And, slowly, everything became bathed in darkness and Audrey, cold suddenly, shivered and walked back to the house. . . .

It was at that precise moment, in the dimly-lit doorway of a stable only a mile away, that the two boys looked up from their game of cards and stared at one another.

“Did you hear that?” one of them asked. “How Fuego began to kick, just as the moon was covered by the big cloud?”

“That horse is nervous lately,” the other boy said. “Maybe it is because he knows that he will become a movie star in only a few days, that the beautiful Audrey Hepburn will soon be riding him in front of all those cameras. . . . Maybe it is because soon he thinks that he will be asked for his autograph—and he cannot write.”

The two boys roared with laughter.

But in the midst of their laughter, from the stall, they heard the kicking again—violent this time—four angry hooves slamming against the boards in heavy, stupendous fury.

“It is just a bad night for him,” one of the boys said then, his laughter gone. “He is really a good horse.”

“Yes,” the other boy said.

Uneasily, they got back to their game. . . .

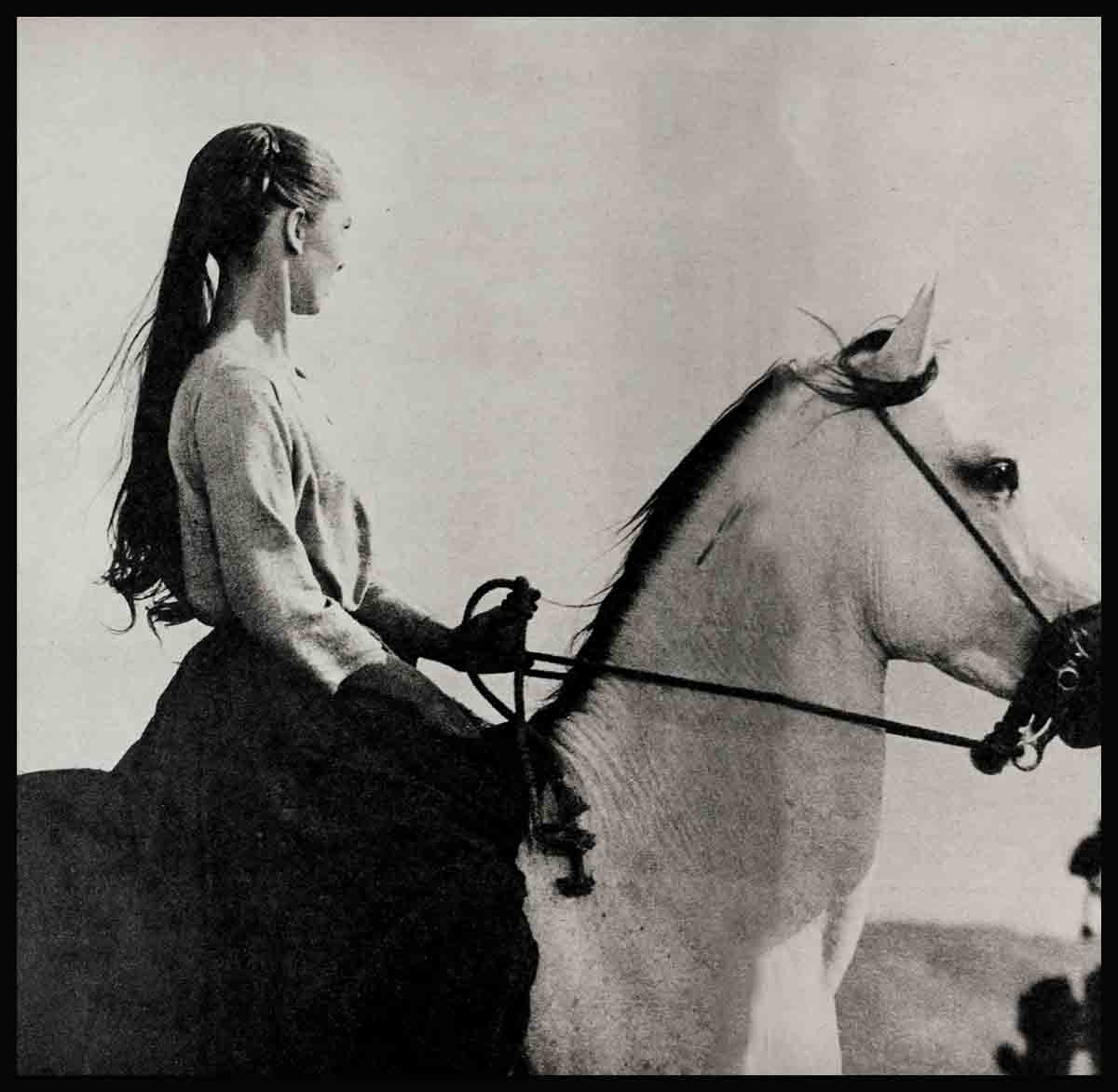

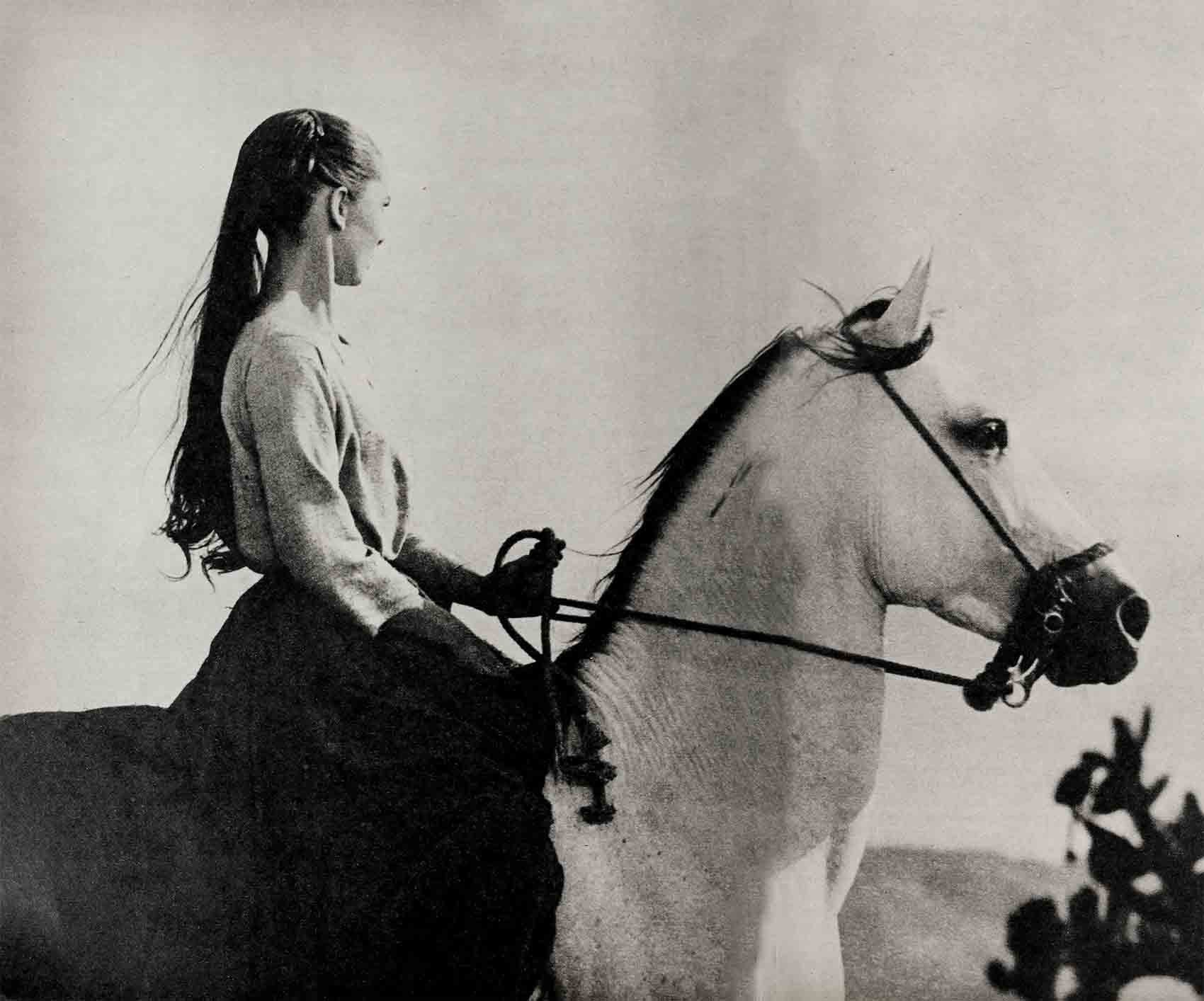

Audrey loved Fuego from the minute she saw him. And she felt enraptured now, sitting atop the handsome stallion, alone, way out in the middle of the windy, sun-filled field.

She was glad, she thought to herself, very glad she hadn’t let the director talk her into using a stunt girl for this scene. True, she’d had her private doubts at first about doing her own riding. She wasn’t a very good rider. She didn’t even like horses, particularly. But one look at Fuego that morning—so proud-looking, so white, so beautiful—and what fears she might have had were gone.

Sitting atop him now, she waited for the signal. Half a mile away, on the other side of the field, she could see the cluster of men and women—the movie’s production crew—getting ready. In a few minutes, she knew, Burt Lancaster, her co-star in the picture, would mount his horse and the director would fire a gun and the action would begin.

Waiting, she went over her instructions:

At the signal, your horse and Burt’s race toward each other. As you approach Burt, you turn your head and look at him. You pass one another. After you pass, you turn your head forward again and keep riding until—

The gunshot sounded.

“Miss Hepburn will live,” said the doctor, “but I cannot guarantee she will ever move . . .”

The marvelous gallop

“Here we go,” she said, aloud. “It’s just you and me now, Fuego.”

She patted the horse’s head, gently.

And then she gave a quick short tug at the reins, kicked Fuego’s sides and they were off.

The gallop across the field was marvelous. Swiftly, surely, the stallion sped through the sun and the wind, and Audrey began to feel her heart beating fast inside her, excitedly, joyously, and she knew—for these few moments, at least—that she and this magnificent creature on which she rode were one.

She looked down at one point, at the blur of brown earth below, spotted with fleeting rocks and cacti, and she began to laugh, like a happy child.

When she looked up again she saw Burt, on his brown horse, approaching.

She knew that she was in camera range now and that in a few seconds they would pass.

She got ready.

But then, an instant before they passed—very suddenly—Fuego stopped and reared and threw her.

And Audrey could hear herself screaming, flying backwards through the air. . . .

She had no idea how long she’d been lying there when she came to. She knew only that her face felt heavy with sweat and that her back felt heavy with pain and that a lot of people were talking—some in Spanish, some in English.

She didn’t open her eyes.

But she listened to the voices.

She realized after a while, from the talk, that she was still lying on the spot where she had fallen, that no one had dared to move her, that they were all waiting for the local doctor to be driven out from Durango.

She was afraid. “Mel!” she called out.

The talking around her stopped.

“Mel!” she called again.

“Señora,” she heard a voice answer her.

She opened her eyes.

A man, dark and old and gentle-looking, leaned over her.

“I am the doctor,” he said. “I have just arrived. If I may examine you—”

It seemed to Audrey that he had barely begun his examination when he stopped and looked into her eyes, sadly, worried, as if he too were afraid now.

“Will you give me your right hand?” he asked, after a moment.

“Yes,” Audrey said.

She tried to move the hand.

But the nerves inside it seemed dead, and she couldn’t.

Straining, she tried to move her other hand. But again, she couldn’t.

“My body feels numb,” she said, finally. “The only thing I can feel is my back . . . the hurt. It hurts so much, doctor.”

She took a deep, obviously painful breath.

She closed her eyes again.

“I cannot move,” she said.

“I cannot move.”

The doctor took a handkerchief from his pocket. As if there were nothing else he could do for her at this moment, he wiped some of the perspiration from her forehead.

“We will get you to bed, in your house,” he said. “You will be more comfortable there, my child. You will see. . . . And then we will see what we must do for you. . . .”

The phone rang in Mel’s office at the studio just as he was about to leave for lunch.

“Audrey?” he shouted, happily, when he heard her voice. “Darling, I was going to phone you tonight. . . . Are you working today, or off, or what?”

“Mel,” he heard her say—and just by the way she said it that time, he could tell that something was wrong. “Mel, when you read the papers tomorrow . . . about the accident . . . please don’t worry.”

“Accident?” Mel asked. “What’s wrong, Audrey? What’s wrong?”

Audrey told him a little about what had happened that morning.

“But you’re all right?” Mel asked.

He waited for an answer.

But instead, for those next few moments, he could hear only a voice moaning, then a few other voices talking in the background.

“Audrey!” He called into the receiver. Audrey darling—are you still there?”

“Daring. . . .”

It was her voice ‘again, very weak now.

“Darling, please don’t worry . . . And I know—when you read the newspapers, all exaggerated, the way they always tend to exaggerate something like this—you’re going to want to come down here, to be with me . . . But don’t . . . Please don’t . . . Right now your work, the picture, that’s the most important thing in your life—and you must stay—”

Mel heard her voice trail off into another long moan.

And then, a moment later, he heard another voice say, in a low whisper:

“Mr. Ferrer? This is Marcia, from publicity. I’m afraid your wife can’t talk anymore right now.”

“What’s wrong?” Mel asked, the receiver beginning to tremble in his hand.

“It’s her back,” came the answer. “She was thrown on her back . . . She can barely move anything but her head. Ever since we got her back to town she’s insisted on phoning you, so you wouldn’t worry when you heard about the accident. And in order for her to talk, I had to hold the phone to her mouth. Because she can’t even use her hands, Mr. Ferrer. . . .”

Dazed, Mel hung up a few moments later.

Then, frantically, he picked up the receiver again and phoned a friend, a doctor.

“Audrey’s been in an accident, in Mexico,” he said. “Can you drop everything and fly down with me this afternoon? It sounds bad. It sounds very bad.”

The doctor said he’d meet Mel at the studio within the hour, ready to leave.

Then Mel phoned another friend, Jim Hill, a producer. He told him about Audrey and what had happened. “There are no commercial flights to Durango, Jim, and to rent a plane takes hours and I was wondering if I couldn’t borrow yours—?”

Hill interrupted to say that his plane and pilot were always available to Mel at a moment’s notice.

Finally, the two calls made, Mel slumped into a chair.

Helplessly, he began to cry.

“Oh God,” he mumbled, “help her, help her . . . please God, please help her. . . .”

At Durango

Mel listened as his friend, the doctor, spoke.

“My examination shows that two of her vertebrae are broken, that we probably won’t know for some six to twelve hours whether the paralysis caused by this ’ breakage is temporary or not. . . .

“The Mexican doctor has.done a good job. What little there is to do in cases such as this, he’s done . . . Meanwhile, I’ve given Audrey something to make her sleep. It’ll do her good.”

He looked down at his watch.

“It’s after midnight, Mel,” he said. He smiled. “I don’t think a little sleep would hurt us any right now, either.”

Mel shook his head. It had been a rough trip, all right—the weather had been bad, the plane had been forced down by fog at one point, for a while it had looked as if they might never make it.

But now that it was over, and he was here, one room away from Audrey, he knew that no matter how exhausted he was he would not be able to sleep.

“You catch a nap,” he said. “I’d rather wait up.”

The doctor shrugged and went to the room that had been prepared for him.

And Mel turned and looked at the door that led to the room where Audrey lay.

“Señor?” he heard a voice whisper, a couple of moments later.

It was Pablo, the chauffeur. He had been waiting in the kitchen, for a moment alone with Mel. He glanced at Mel.

“Señor, before I go home for the night, maybe I can get you some coffee?”

“No . . . thank you,” Mel said.

“At least these I hope you will take, then,” Pablo said, handing Mel a tiny bunch of flowers. “I took them from the church just now. They are part of many offerings the townspeople have brought there today for your wife . . . You see, señor, the people of Durango love your wife very much. Not only because she is beautiful, and an artist. But because she is kind. We all heard today of what she said in the car as she was being driven back here this morning, sick, in such terrible pain. We heard how she said, ‘I feel so sorry now for all the people here. They are so poor. And many of them were working in my movie, earning a few extra pesos. And now, with the picture stopped, it will be a long time before they can look forward to earning extra pesos again!’ . . . Yes, señor, we heard how in her pain she thought of us. And in gratitude today, in the hope that the Lord will hear our little prayers and help her, hundreds of us have gone to the church. Many of the men have brought their best ears of corn from their farms and laid them at the foot of the Virgin Mary. Some of the children have brought the hard candy they always save for Sundays. And the women have brought flowers from the little gardens they tend . . . These flowers you hold are only a few of all those now in the church. I thought you might like to have them.”

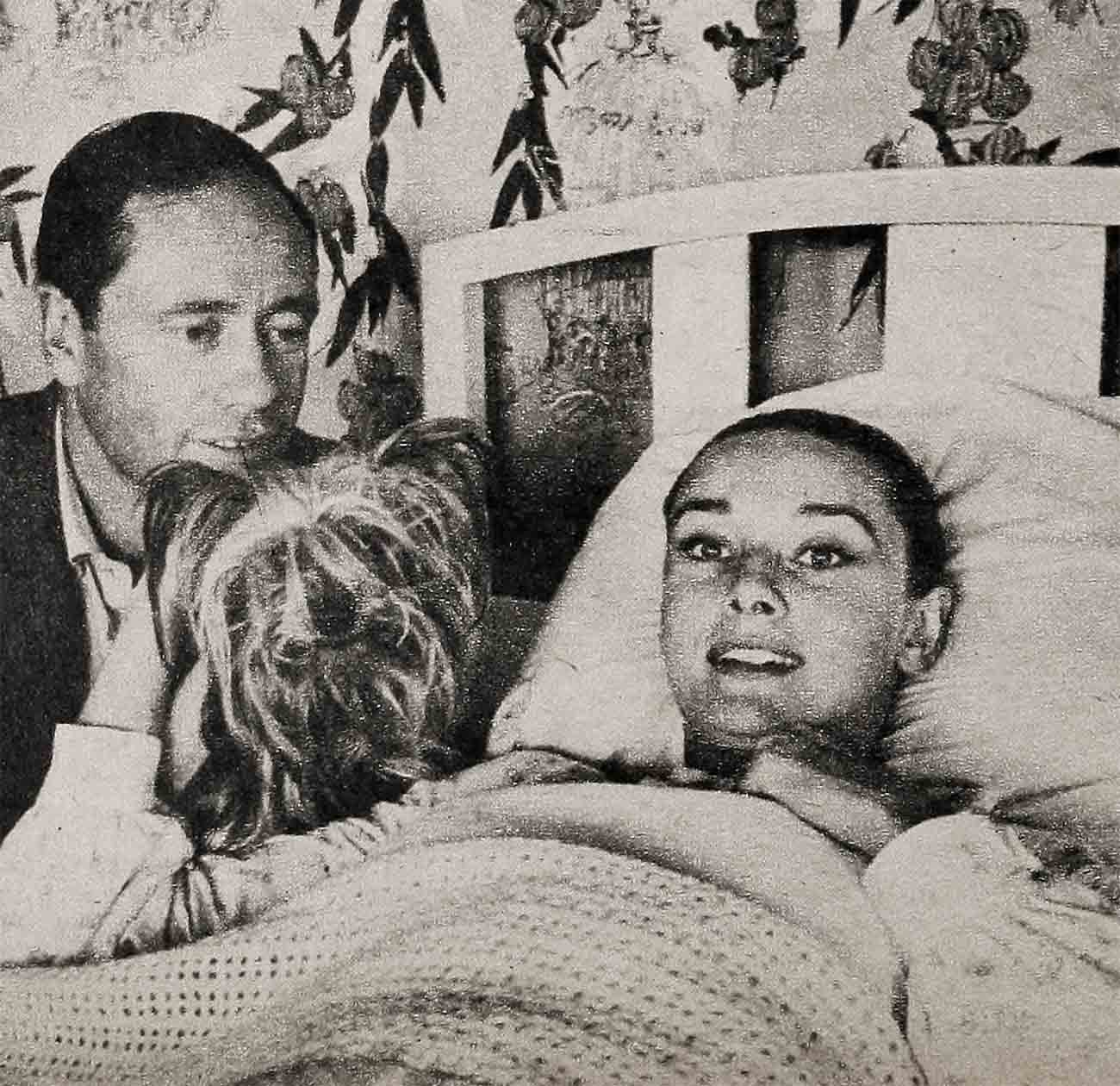

Too moved to say anything, Mel carried the bouquet into the room where Audrey lay asleep and placed them on a table. And then he sat on a chair, at his wife’s bedside, for hour after hour after hour, until finally his shoulders hunched forward and he, too, fell asleep. . . .

The hand at his brow

“Mel?”

He heard the voice, in his sleep.

“Mel?”

At first, he thought that he was dreaming—about other mornings when he had been asleep and when Audrey, lying next to him, had awakened him by placing her cool hand on his head.

But then, for a third time, he heard the voice and his name. And he knew now that he was not dreaming, that he was awake, still sitting in that chair, next to her bed, his head resting on the bed.

And he knew, too, that it was her hand that lay resting on his head.

He couldn’t believe what he thought was happening.

Slowly, he moved, reaching for the hand on his head and grasping it, and raising his head at the same time.

He looked at Audrey. She was smiling.

“You’re here,” she said. He nodded.

Then he looked down, at the hand he was holding.

“Yes . . . I’m going to be all right,” she said. “Don’t worry, Mel—not any more. Did you see? My hand? . . . I moved it, and I’m going to be all right.”

“You are,” Mel said, nodding again.

And, believing now, he kissed the hand he held—lovingly, gratefully. . . .

THE END

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following day, Mel flew Audrey back to California. She spent a few days in a Los Angeles hospital, and was then taken home. According to doctors, the temporary paralysis that set m after the accident is completely gone. And she is now completely recovered and back at work.

Audrey is appearing in M.G.M.’s GREEN MANSIONS and will soon appear in Warner Brothers’ THE NUN’S STORY and United Artists’ THE UNFORGIVEN.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1959