The Boy Who Swallowed A Dream

This is a story about a boy, a little boy who swallowed a dream. And this is where the story begins . . . where it ends, nobody knows.

It was a bright, clear day and the sand on the beach was hot and sun-soaked. The little boy clowned about the edge of the water and talked merrily to himself for he was alone.

As he stumbled, picking up broken crab shells, a giant wave rolled in and carried him out towards the sea. By the time the boy collected his balance, the shore seemed forever away. He began to swim back and, somehow, while he floated and kicked and struggled against the Pacific, as he fought back the ocean and coughed up the salt water, things became confused. But all the time, he knew he wasn’t going to drown. When, at last, he stumbled onto the beach, seven-year-old Aldo Ray knew why he was spared. He had swallowed the ocean and fought the waves—and he had found his dream. Filled with overpowering victory, he shouted his dream to the sea. “I’ve lived to be president. I want to be president of the United States. And I thank you for showing me the way.”

When you have swallowed a dream, it is not easy to get rid of it, and the dream was still with him ten years later on the island of Saipan. A sailor third class with nothing to do in the evenings before the Japanese bombers came over, he practiced writing campaign speeches. When the alarm sounded, he put his paper away and strolled out to look at the sky.

For fifteen nights he stood beneath the stars and watched the planes come over, their exhausts cutting swatches of flame in the midnight sky.

The sixteenth night, he kept the same watch—on a hill that sloped down to the ocean below. The first wave of planes came in from the beach and passed over him.

The dream flopped a little in his stomach as he looked down at the beach. In the darkness, it looked almost like the California coast. Following an impulse it he cannot yet explain, he slid down the cliff.

“I thank you,” he said to himself and to the ocean, softly, so that no one could hear and laugh. “I thank you for showing me the way. . . .”

And above him, the place where he had watched for fifteen nights was torn to fragments by a bomb.

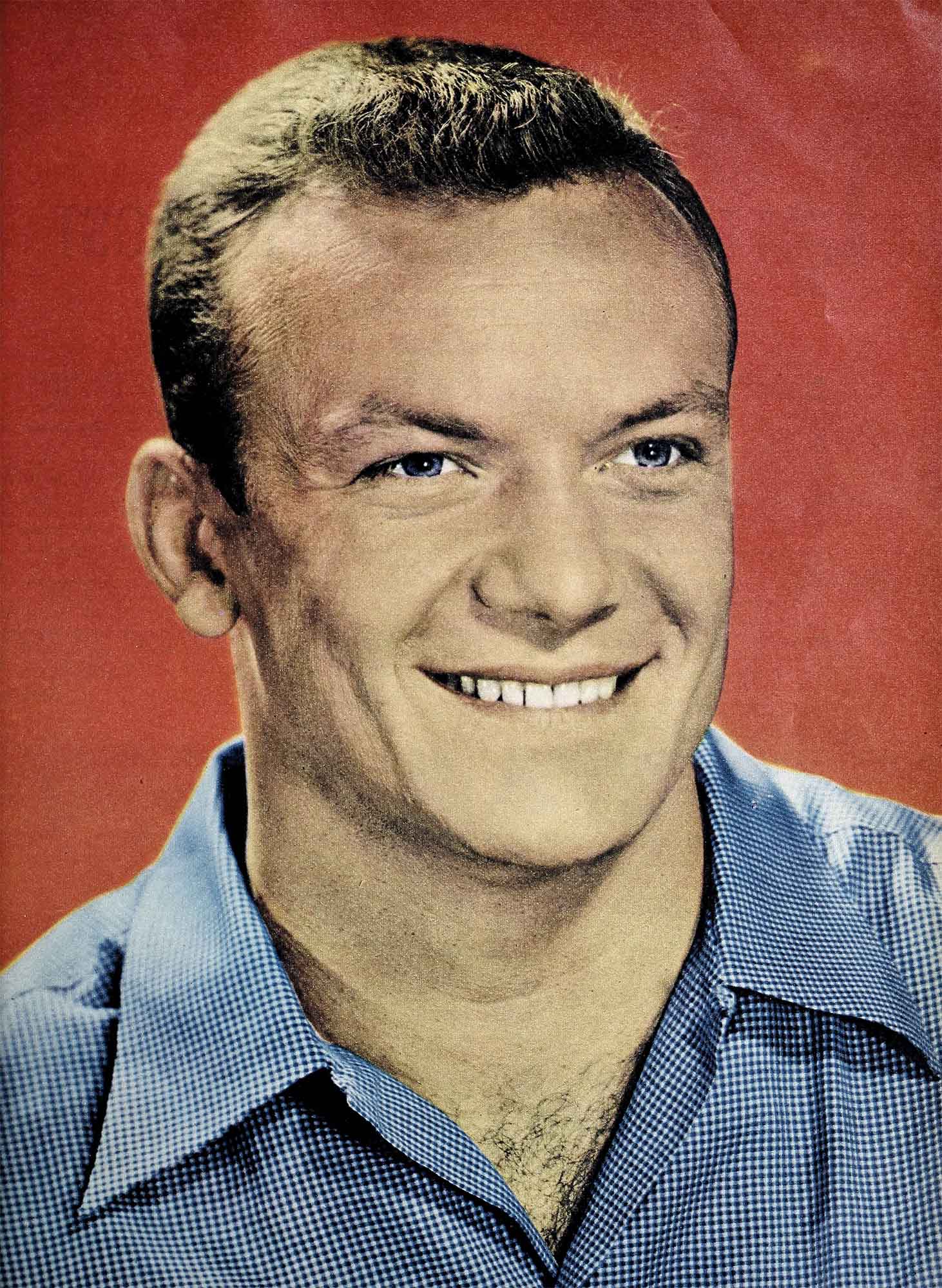

Aldo Ray will most likely never be president of the United States, and he has not quite gotten used to this fact yet. This is not to say that he couldn’t stand a chance to be president if he wanted to, but chance and fate have made him a movie actor instead.

The twenty-nine-year-old, frog-voiced ex-politician does not know whether to be pleased or angry at fate and chance. “You ow,” he says a little wistfully, “I think could have made a good president.”

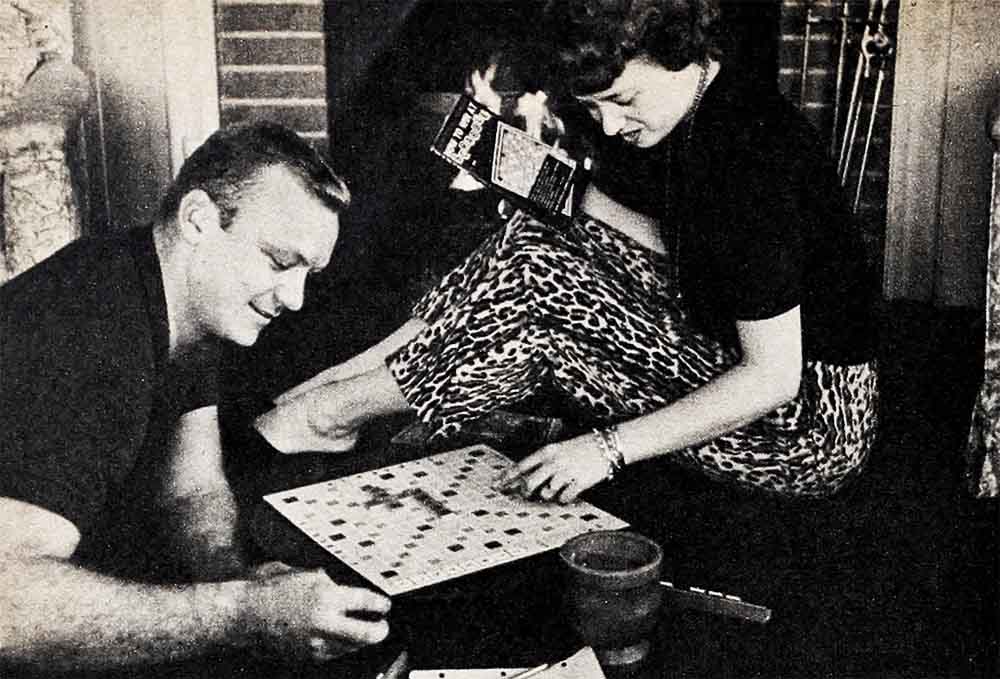

He puts one arm around his wife when he says it though, as if to remind himself that she is part of this new dream. He does not say that meeting Jeff Donnell, knowing her, building with her a house overlooking the city is worth anything that he might miss because of it. He does not need to say it. It is in his eyes.

“He’s a good actor, too,” Jeff says. “In fact he would be good at anything he wanted to do. I think Aldo was born that way.”

“Thanks, honey,” Aldo says. “A good husband, too?”

Jeff deliberates. “You forget to hang up your clothes, and you forget to tell me anyone’s invited us to a party until three days after the party’s over, and you even forgot to bring money for our marriage license, but . . .” she smiles at him, “ . . . a pretty good husband, too.”

They are two mature people, building a life together on common knowledge and years of friendship and love. They waited a long time before they got married. For one year they resisted all the friends who arranged wedding parties for them in Las Vegas and Reno and New York. Then the friends gave up. And Aldo and Jeff smiled and looked at each other and were sure and decided last October on a honeymoon by the sea.

And Jeff is right about another thing. He is a good actor. With a little more training and a little more time, he will be a very good, a very versatile actor. Chance and fate have nothing to do with that. Their job was begun and over with five years ago.

And the part they played was that of a nonexistent car. It happened because Aldo’s brother Guido did not have a car. Guido read in the San Francisco newspapers that Columbia was looking for football players to be in “Saturday’s Hero.” He persuaded Aldo to drive him down. once there, Aldo decided to be interviewed, too.

The man in charge listened to him and laughed. “Come back when you don’t have

a cold,” he said.

“I don’t have a cold,” Aldo said. “I talk this way.”

“Have you ever acted?”

“No.”

The man shrugged. “If you can’t act…”

“I can act,” Aldo said. “Just listen to me.” It was a challenge. At that time, at that place, it was the biggest challenge in the world. He had already made a start on his political career. So he delivered one of the campaign speeches that had elected his constable—a job equivalent to police chief—of Crockett, California. The speech won him a part as John Derek’s roommate.

The same challenge that kept a young boy from drowning made an older one do something that happens once in a million times, get a good part in a good picture without ever having acted before. That was not luck. It was just something that happens to people who are foolish enough to swallow dreams.

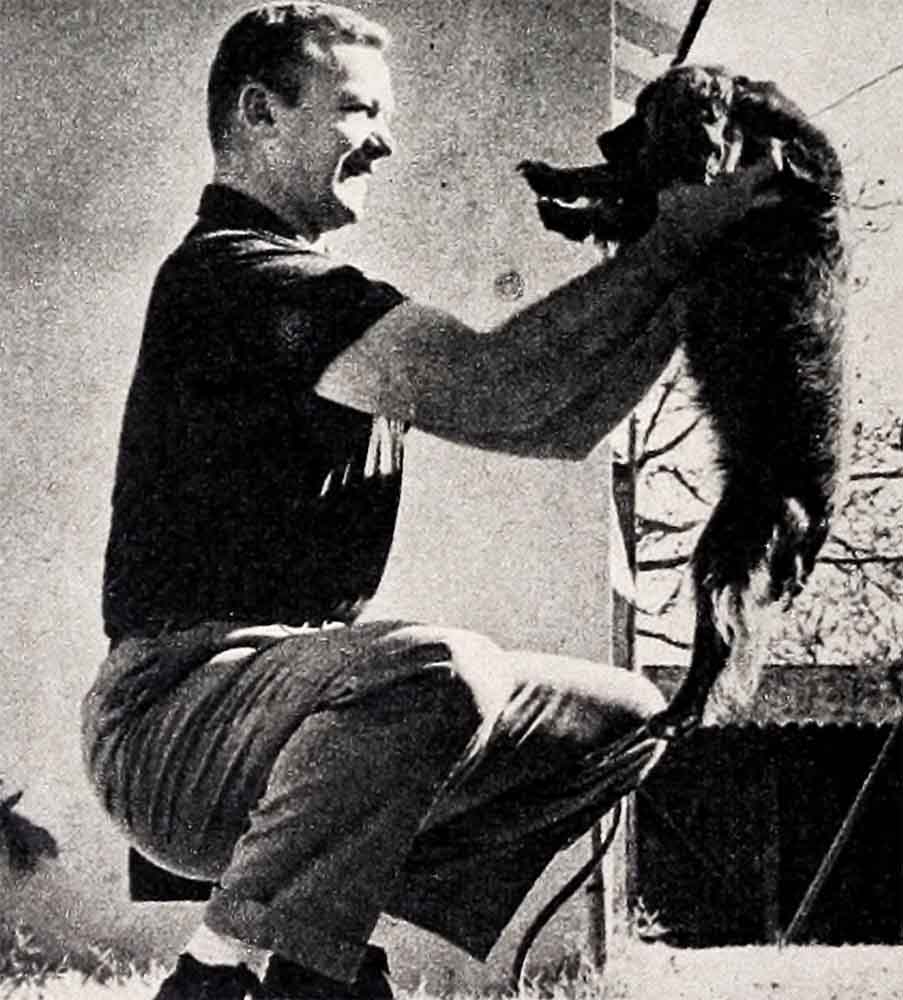

There is something else that seems to happen to such people. They grow up to be very nice. Intelligent, not overly critical of life or people, their hair turned golden by the sun, they are always bounding after rainbows, and the sound that they make is laughter.

There was nothing much for Aldo Ray to laugh about when he was a child. Born September 25, 1926, he was three years old when the Depression left men begging for jobs as day laborers at the sugar refinery m Crockett. Silvio da Re, his father, was one of the lucky ones. His job paid $4.50 a day. It was enough for a man who had only come to America nine years earlier, a man who still spoke Italian in his home.

By 1937, there was not even a job. There was a strike instead, a strike so important that it was written about in the New York newspapers, so violent that for three months the schools in Crockett were closed.

Silvio and his wife, Maria, and their six children sat home and waited, while goons and scabs from the factory fought in the streets outside. This is Aldo’s version of the waiting:

We didn’t have much money, but what did that matter? Every day we looked at the wine that Papa had made the summer before, to be certain it didn’t turn sour. Then we went fishing. We fished every day, and there was always fish soup on the stove and fried fish for supper, and Guido and I—we were the oldest—even made some money. I was eleven and Guido was ten, and we collected old scraps of copper. We averaged fifty cents a week from the junkman.”

That was not Aldo’s only job. When he was eight, he had gotten a job in a grocery store. He worked after school, Saturdays and Sundays. In return, he got five dollars a month and all the fruit and vegetables that were about to spoil. He got a bonus, too. Each week the market held a drawing tor free bags of canned food and vegetables, a drawing that was more important to them than a drawing today for a 1955 Ford. And each week, the owner put one of the bags aside for Aldo.

Even now the owner smiles when he thinks of the boy. “He was always laughing, always dreaming, always running very fast as though there was something ahead that he wanted to catch up to and that he was still too young to catch. But I think we all knew that he would catch up to that goal of his someday.”

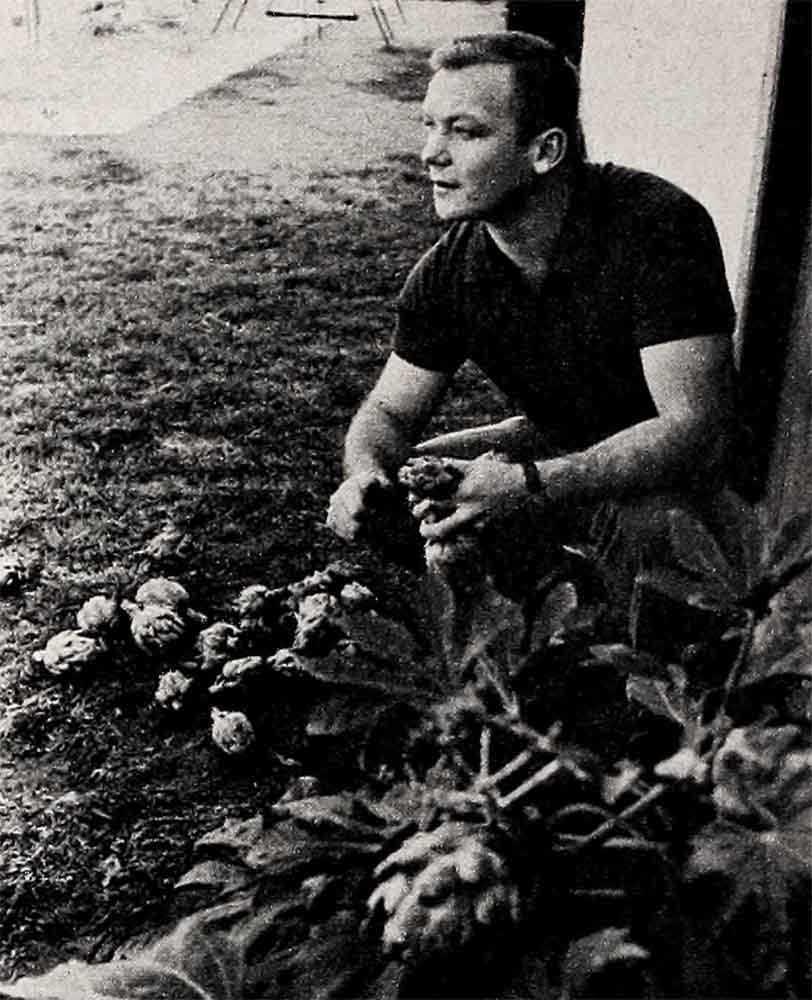

Aldo does not think that he became really independent until he was thirteen. That summer, Angelo, a friend of the family, gave him a job. Angelo had forty acres of land where he raised artichokes, and he and Aldo worked the land alone.

Angelo called him “Il Matto”—the crazy one.

“He was, crazy,” Angelo has said. “I take him out to a field—a big field. I tell to him plow it. I leave him. He does not come in to lunch. Then, about two o’clock, he comes back. He is covered with dust, with sweat.

“ How much have you done?’ I ask him.

“ ‘How much?’ he says. I’ve finished it.’ ”

Angelo scratched his head. “A field that would take a hired man a day and a half. A field I would plow in a day. And he—Il Matto—he does it in four hours.”

For his summer’s work, Aldo got room, board and $60. He took the money home, put fifty dollars in his pocket and went to talk to his father. He went to talk about football. In his first year of high school, he had been on the freshman team and he had broken a leg. But now he had plowed all summer, and he knew the leg was well.

He took the fifty dollars out of his pocket. “Papa,” he said, “for the doctor, when I broke my leg.” Then he smiled.

“Now,” he said, “now I can play football again.”

The other ten dollars bought two pairs of corduroy pants. Never again did his family pay for his clothes.

“I was the oldest,” he has said. “I had to do it.”

The next summer his salary was tripled. Angelo felt that his fourteen-year-old helper was worth the money.

When he was not working, Aldo was winning prizes and presidencies. He was an officer of every class from the second grade through the twelfth for at least one semester. The other semester of each year he was such diverse things as Thrift Manager (second grade), Keeper of the Rabbits (third grade), and Commissioner of Boys’ Athletics (sophomore year).

He has been characterized as ambitious, determined and determinedly forthright. One of his teachers had reason to remember the last. When he was graduated from grammar school, he took the prize for athletics, the prize for general scholarship, the prize for English, the prize for sportsmanship and the prize for mathematics.

The American Legion Award for all-around student was given to another boy. After the assembly, he walked politely up to the judges and asked why It seemed to him that if he had won all the other prizes the school offered, he was its all-around student. He still feels this way.

It is not conceit. It is an honesty that is almost brutal and it is still with him, both as his greatest asset and his severest fault. It was also the cause of his first quarrel with Jeff.

They had been married three weeks, and friends were coming to dinner. Jeff had made hors d’oeuvres and Aldo had been official taster. The hors d’oeuvres was, he said, the worst thing he had tasted in his life.

The rest can be imagined.

Despite his brilliant honesty, he is not a diamond in the rough, waiting to be pounded and polished into shape. He was president of the California Scholarship Federation at Crockett High School for two years and he was awarded a scholarship to the University of California when he graduated.

But it was 1944 and there was a war going on. So Aldo Ray became Seaman Ray and was sent to Saipan. After a while, Saipan was no longer target practice for the Japanese. So, when a notice went up on the bulletin board that tryouts would be held the next day for the “frogmen”—underwater demolition teams—Aldo decided to volunteer.

So did every one of the other one thousand two hundred and fifty-four sailors on Saipan. There had been a rumor that the frogmen would be sent back to the United States to train, and they all showed up at the edge of the Pacific for the tryouts.

They were pushed into four lines by the harried commanding officer, told to swim to the coral reef about a mile away and sent off at three minute intervals.

“Some of them couldn’t swim at all” Aldo said, grinning at the thought. “They just thrashed around and tried to keep from being stepped on. Finally, one of the officers waded in and pulled them out”

Aldo was in the last line. A hundred yards out, he had passed most of the men in the third line. Five hundred yards from shore, he was first. From then on, he merely lengthened his lead. He was sitting on the coral reef for almost five minutes before the second man panted up.

Aldo and thirteen others were chosen and shipped to Hawaii for training. His training was brief. He managed to get himself attached as a replacement to a team that was going back to the South Pacific, Their job was to reconnoiter and report everything they saw and felt from the point they were dropped off (usually five hundred yards from shore) in to the beach. Three days before American assault troops landed, Aldo and his team swept the beach at Okinawa.

As they did in all their missions, they swam in when it was turning light—in the early morning. They had no aqua lungs, only swim fins, goggles and knives, and they swam on the surface. But the Japanese shore defense never even found out they were there.

A little later in the war, they were dropped off the coast of Japan. Their job then was to make sure there were no mines, and their mission took them less than forty miles from the bombed ciyt of Hiroshima.

After that, the war was ended for Aldo. He traded his swim fins for his old university scholarship. And the old dream began to flop around a bit again. He looked for a place to start. He decided to run for constable of Crockett. It was a fine job, but there was one obstacle. The man who was constable had been doing a good job for fifteen years.

It is almost impossible to dislodge man who has been doing a good job for fifteen years. It is even more difficult when you are still in college and you are only twenty-three years old. But Aldo did it. He was elected town constable.

He is very proud of the year he spent in office.

“We have a jail in Crockett, but I didn’t use it. I didn’t make one arrest that year. There was no serious crime, and I’ve always figured that it’s senseless to put a black mark on a man’s record for a little thing. So when the old pensioners would get drunk and start trying to knife each other, I’d just go down break it up and make the soberest man my deputy.

“Then the two of us would pile the rest in my car. I’d open the windows and take them back to their rooming houses. By the time we’d delivered the last one, my deputy would be sober enough to walk home himself.”

He was a good constable. When one of his “boys” got into trouble with the county sheriff and was put in jail because he couldn’t pay a $100 fine, Aldo paid the fine.

“He had a wife and a kid,” Aldo said. “I couldn’t do anything else. And he paid me back—every bit of it.”

It was then—when he was worrying about his final exams and thinking about running for Congress in a year or two—that his brother Guido needed a car.

After that first picture, he went back to Crockett and bailed out more drunks. Then he got a call to test for the lead opposite Judy Holliday in “The Marrying Kind.” (The person who played the test with him was Jeff Donnell, and that was the beginning of that.) When he got the part, he resigned his office and took a house by the ocean in Santa Monica.

There were a few more parts, and then he sat by the ocean and waited. After Jeff’s marriage broke up, he learned about Jeff, met her friends, took her son, Mike, to the movies, read her daughter, Sally, fairy tales.

He learned that he and Jeff both liked to cook and he would come over to her house at four in the afternoon, his hands full of difficult recipes and the groceries he’d bought to try to make the recipes. Her first gift to him was a snail tray (for serving cooked snails). His first gift to her was just as practical. It was a gold bracelet with a heart engraved “Happy Birthdays Forever.”

“It was engraved that way,” Jeff says wryly, “so that he could forget all the rest of my birthdays.”

His first gift after their marriage was practical, too. They were honeymooning among the rocky crags of Santa Cruz and his gift was a pair of tennis shoes.

After the waiting came “Battle Cry,” in which he plays Andy and in which he makes the audience leave the theatre thinking of Andy most of all. “Battle Cry” and success. High point of the success right now is “The Gentle Wolfhound,” which he is making for Columbia and in which he plays his first real romantic lead.

Has he changed? A sunbeam doesn’t change. It may grow more confident of its power to shine. It may stop swimming so fast across the sky. It may grow a little older and settle down for a while on a comfortable cloud. But a sunbeam doesn’t change.

Neither does a boy who has swallowed a dream. The dream gets a little bigger perhaps, or even a little smaller. But it still churns around after the last field has been plowed and the last prize won and the last beach unmined.

It causes a queer feeling in the stomach when the last part has been won and the last performance has been the best possible. That is when it pulls you a little faster and heads in another direction.

And when that happens don’t take any bets that Aldo Ray won’t be president of the United States after all. Don’t take any bets at all.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1955

No Comments