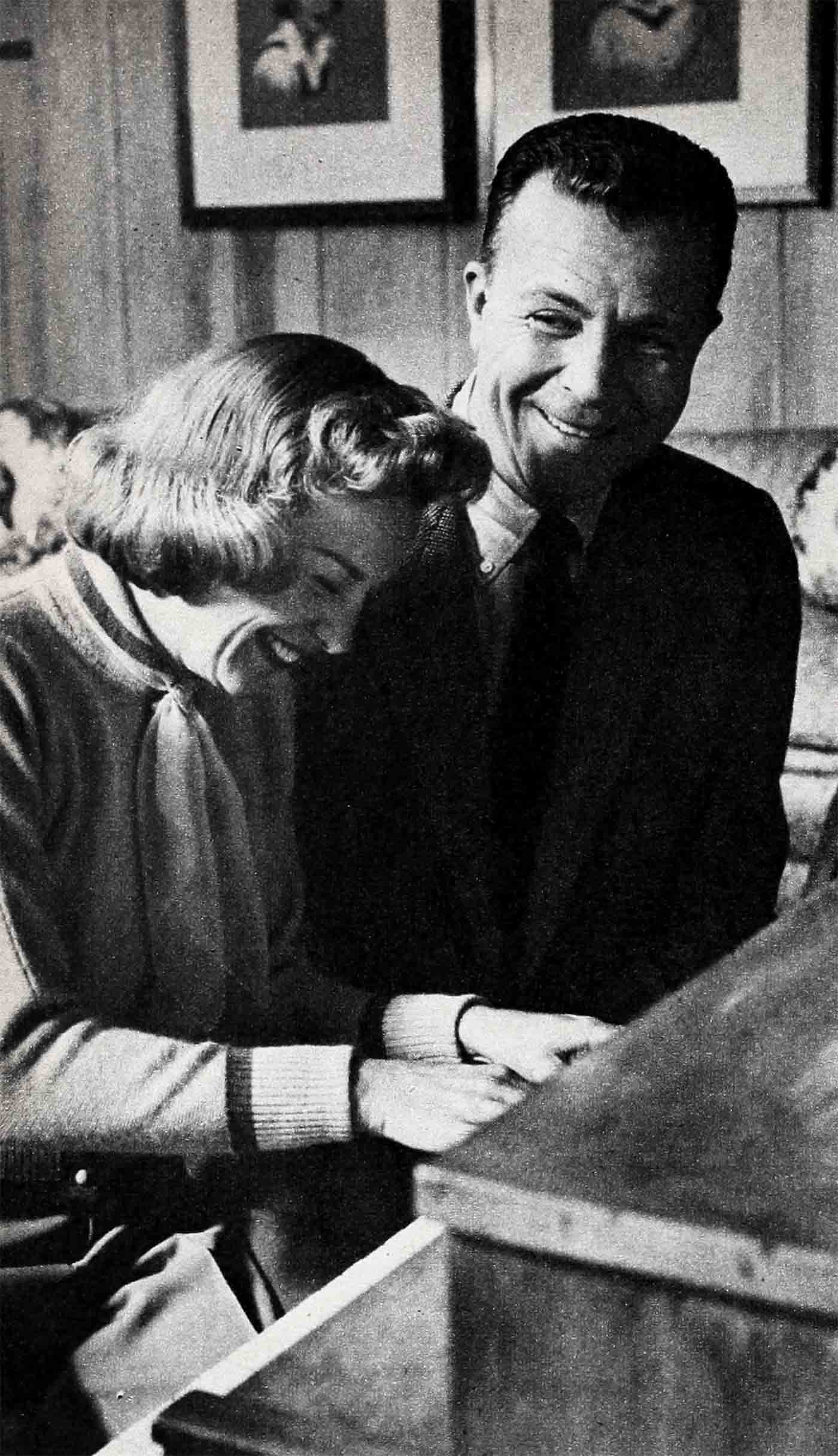

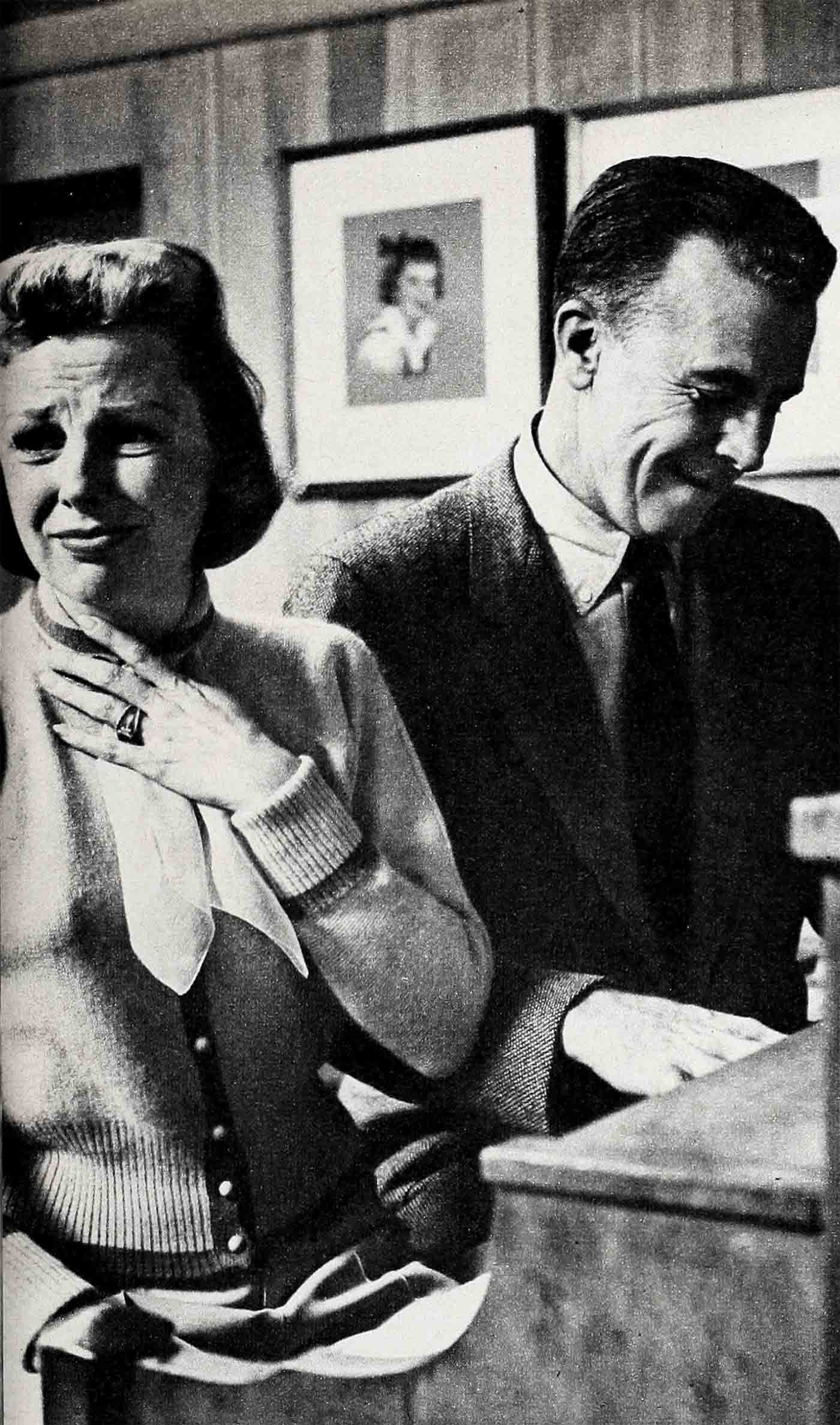

Rumor’s Targets—June Allyson & Dick Powell

Rumors of an impending separation in the Powell household persist. To read the papers, you’d think that divorce is a simple. matter, that love’s too uncertain to be believed, that marital vows may be recalled as a casual conversation that happened to take place one day.

You can’t crowd ten years of memories into a sentence. You can’t know the meanings of those memories unless they belong to you. You can’t cut the roots of a marriage with sharp, insinuating words. When a couple has worked day by day, year after year, to build and strengthen their marriage, it’s unlikely that they’ll suddenly turn their backs upon it and call it worthless. A marriage doesn’t end so easily. A real marriage doesn’t end at all. And though no one seems to have thought of it as yet, this may be the very reason that June and Richard Powell are still together.

On August 19 they celebrated their tenth wedding anniversary. Richard had warned June even before their first year was over, “I never remember birthdays or anniversaries, so don’t be angry. You’ll just have to forgive me.”

“Oh, Richard,” she’d cried. “Try to remember. They’re such sweet ideas.”

Along about the first of last August, due to the force of a nine-year habit, Mr. Powell inquired as to what Mrs. Powell might like for a gift. “A Thunderbird,” she said. “That’s what I’d like. With a Continental kit on the back.”

“A Continental kit is too much added expense. You can’t have it,” replied her husband who, on a hunch, had already placed an order for a Thunderbird in her favorite color, pink . . . with a Continental kit on the back.

“I drove it home a couple of days before our anniversary,” he smiles. “June ran out and danced around it and you’d have thought she was Pam’s age.”

After ten years, he still delights in delighting her.

After ten years, she goes shopping for gowns and stands before the store mirror staring critically at her reflection. “Do you think my husband will like this one?” she asks anyone who happens to be standing nearby. She still adds softly, “I want to look glamorous. For Richard.”

All might have been different if Richard had lacked his ever-present wisdom and patience and understanding, if June had failed to find the courage to grow up.

Even Richard had his doubts during their courtship. In fact, he refused to admit it was a courtship. The entire idea was pretty ridiculous to him. June Allyson was a cute kid whom he’d met casually when she was doing a show on Broadway. They’d met again when they made “Meet the People” at M-G-M. And again when June and Nancy Walker were sent to New York for theatre appearances.

Richard was in town at the time and he caught their show. The girls were good, but there wasn’t a great deal they could do with sad material. Afterwards, he went backstage. “Bad, huh?” said Nancy.

“If I tell you I’ll only depress you more,” he said.

“Impossible,” said June. So he sat down for a while and tried to cheer them up.

June Allyson was only a kid, of course, but she was such a sweet kid that once back in Hollywood, he thought he’d call her. June’s housekeeper, who doubled as chaperone, told him that June was in bed with pneumonia. “Tell her to be a good girl and get well and I’ll take her to dinner sometime,” said Richard.

“Sometime,” muttered June when she received the message. And the more she said it the more distant it became. How do you circle “sometime” on the calendar?

A few evenings later, Richard stopped by the apartment with an armful of roses. Several of June’s friends were there and Richard spent the evening playing bridge with the housekeeper. “That’s when June started flirting with me,” he says.

“As I recall, you were the one who flirted with me,” corrects his wife.

Eventually she recovered and he took her out to dinner. They liked being together and, as the weeks went by, they found themselves together quite often. But it was no courtship. Anyone could have told you. Richard Powell, for instance.

However, confusion set in the night he delivered her to her doorstep and leaned down to kiss her good night. June drew away. “I have something to ask you,” she said. And it took every ounce of her nerve.

“All right,” said Richard.

“Just what are your intentions?”

He looked at her standing there so primly. “Had any other offers?” he inquired.

“Two,” she said and stepped inside and closed the door.

He went home, but that night he couldn’t sleep. He tried counting sheep, but they turned into proposals from two other guys. What if she were serious about accepting one of them? How could she when she was in love with him? “As it turned out I had to ask her to marry me several times,” he says. “She became quite coy.”

“I liked to hear you ask,” she says.

The wedding was at the home of their friends Bunny and Johnny Green. They’d set the time for 7 P.M., but around noon June began to worry. Her maid of honor wasn’t ready. Her housekeeper would surely never be dressed in time. To save their sanity, they shoved a book at her and commanded rather heartlessly, “Read. Don’t talk.”

When it was time to leave for the Greens’, June insisted on taking the wheel. And talking. “Out of the way,” she crowed to the evening traffic. “I’m on the way to my wedding!”

There were tears in her eyes and she walked down the stairs to stand beside Richard. “And those eyes were four times bigger than her face,” he remembers.

When the ceremony began she hardly heard it. Then the judge’s voice got through to her. “Do you take this man to be your lawful wedded wife?”

“Do I . . . what?” said June coming out of the trance. The statement was corrected when the laughter stopped. “I do,” said June. “Yes, I do.”

After the honeymoon on Richard’s boat, the Powells moved into an apartment to await the completion of their new home.

Mrs. Powell was on her own in housekeeping. She tried cooking. The first time, they sat down to what the cookbook said was a well-balanced meal. Technically, it was true. However, the meat shriveled, the potatoes would have required identification by an expert, and the salad turned out terribly tired. “Who cares?” Richard.

Richard was a man of many interests. She’d never had time for hobbies or sports. He loved planes. She didn’t like them even when they were standing still, on the ground. So she’d grit her teeth, climb into his plane and they’d be in Palm Springs before she’d breathe again.

Richard was nuts about golf. She’d get up early and head for the golf course. About sundown she’d stagger home, having had such encouragement from the caddy as, “You’re doing fine. In a couple of years you’ll really have the game down.”

The idea was to go around the course with Richard occasionally. “But you’d go out of your mind waiting around for me, wouldn’t you?” she’d ask him.

“Uh huh,” he’d say.

She’d never lived in a house before. There had always been apartments. “I set out to be a real, solid housewife,” she recalls.

One day she went shopping for furniture for the den. The next day it was delivered and put into place. June took a good look at the results. “It’s awful,” wailed the solid. Housewife.

The room was Tudor and the furniture was Early American. And somehow the combination failed to turn out as she’d expected. “Say it, Richard,” she requested. “It does look awful.”

“Well, yes,” he said. “It does.” And the furniture went back the next day.

With each mistake, she felt more foolish, became more afraid to accept the responsibility that she already feared. She began to shy away from it again. How could she make a mistake if he did everything? “She was scared in the beginning,” says Richard. “Her fear of responsibility magnified the mistakes. But after a while I began sort of shoving it off on her, by just leaving things undone. She’d call me and say something was wrong. I’d say, “You take care of it.’

“When we redid the house for the first time, I had to do it. She wanted the same next time. I said, ‘No.’

“It took her a month, but she did it,” he grins. “And she did a good job of it.”

His friends terrified her. “They were all well-established people who had achieved their goals,” says June. “I had just come out and was starting a whole new life. Mentally I was a good deal younger. They all seemed so well-organized and put-together and I never thought I could be.

“But mostly I worried about the fact that they might not think I was right for Richard. I was surprised when they accepted me from the first. And I was grateful. I learned a lot from them.”

There were the Justin Darts and the Leonard Firestones, among others. “I didn’t know where to put a chair or what color it should be when I got it put,” says June. “Polly Firestone never told me anything. She’d just say, ‘Let’s go sit in the house and see what would be pretty where.’

“She steered me into doing things she knew Richard would like. I always thought I’d done them. Now I know I never really did!”

Her career had been the most important thing in her life, until her marriage. Yet she’d wake up and moan, “I don’t feel like going to work today.”

“Then you won’t feel well enough to get your check,” her husband would say.

“Richard taught me that the picture business is actually a business, not a thing you play with,” says June. “And he’d remind me of a fact that would sometimes escape me—that you’re only as good as your last picture.”

“Richard taught me . . .” is a phrase June still often uses. Richard was gentle, but he never pulled punches. “His basic honesty was one of the things that attracted me to him,” says June.

He understood her moods. He’d come home and find her in a black one. “You’re not for me tonight,” he’d tell her. “I’ll go away.”

The scowl would disappear. “Don’t you dare,” she’d grin.

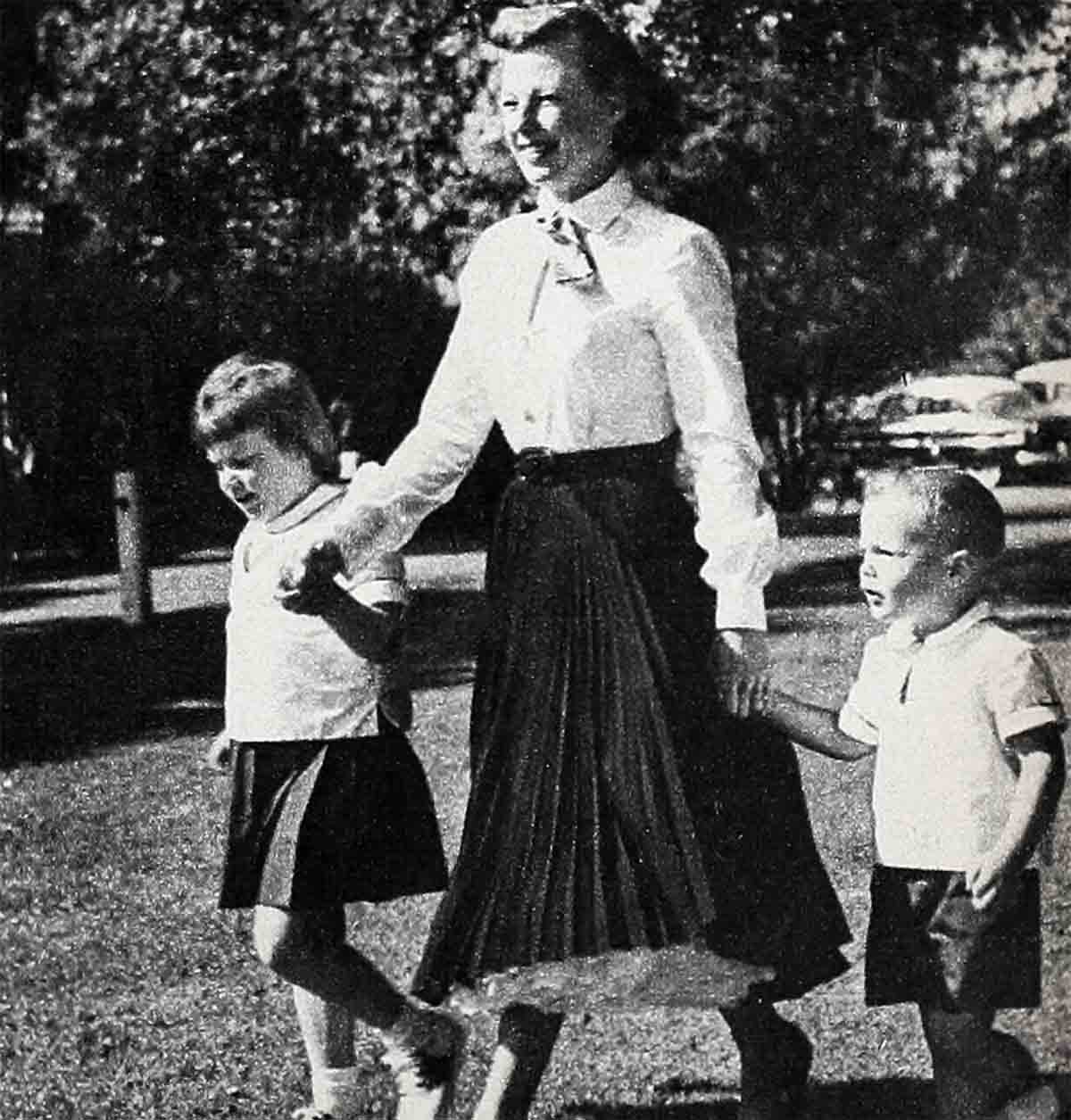

The Powells had one another and they had their work. But after two years of marriage, there were still no children. “When the doctor told me I probably couldn’t have a baby, I was so full of tears I could have flooded a battleship,” says June.

The movie star June Allyson was a girl to be envied, career-wise. But Mrs. Richard Powell was filled with envy for others. Let anyone talk about babies and she’d get a wistful look. Let her overhear a woman complain about pregnancy and she’d explode, “How can any woman say such a thing?”

She wanted to adopt a baby. But Richard balked. “I can’t for the life of me imagine June as a mother,” he told a friend at the time. “Anything new frightens her. I don’t think she realizes the responsibilities of motherhood.”

Finally he gave in and they put their names on the waiting list at the Tennessee Children’s home.

Then came the gossip. There had been rumors before, but the Powells had shrugged them off. Now they threatened to do real damage.

June had to go to New York for radio shows. Richard couldn’t go with her. And the rumors flew. When they reached Richard he realized that they might cost them their baby. He knew that those in charge of the home might hear the irresponsible talk and postpone or cancel the adoption. He called Tennessee to reassure the officials that all was well. And he convinced them.

June returned with a bad cold and the doctor put her to bed. One evening the telephone rang. “Hello, Mrs. Powell?”

“Yes,” said June.

“Hello, mother.”

June was puzzled. “You hab the wrog number,” she finally croaked.

“Mrs. Powell, your baby is here. You have a daughter,” the voice went on.

“Richard,” she said. “Our daudder’s cumb.”

He took the receiver from her hands, held a brief conversation with the party on the other end of the line and discovered he was going to be a father.

They had eight days to prepare for Pam’s arrival. En route to and from the studio June would detour past the local stork shops. She’d come in with her arms loaded. “What now?” Richard would ask.

“More diapers,” she’d say.

He’d grin. “I wasn’t sure you’d remember such practical things. I got some, too.”

But she remembered everything—sheets, blankets, bottles, the delicate little gowns, the booties.

She was at the studio when the nurse arrived with Pam. Richard called. “Hurry home,” he said “She’s here.”

June raced from the studio. She ran up to the nursery. She peered into the crib. “Oh,” she said. “Oh.”

Then suddenly, “Richard, she smiled at me!”

The nurse didn’t have the heart to tell her it was just gas.

When Dick had to leave town on business, he’d call with advice. One time the phone rang in the middle of the night. It was Western Union. “I have a message for you, Mrs. Powell,” said the operator in a bewildered voice.

“Go ahead,” said June.

“The telegram reads, ‘Darling, hold the bottle up straight when you feed her so she won’t swallow air. Love, Richard.”

“Thank you,” June told the operator.

When Pam came along, life changed in strange little ways. “Before,” says June, “it seemed I was always sick. I’d have a cold or an ache or pain and be certain I had some disease or other.

“When Pam arrived, I found I didn’t catch as many colds. I felt fine. When you have a child, you forget about yourself. You put your energy into other things. It’s a great, wonderful responsibility. A responsibility I wanted with all my heart.”

There were the usual disagreements about discipline. More often than not, they didn’t reach the papers.

Pam had a habit of picking up everything within her arm’s length. And she didn’t really care just where she put it down. One night she grabbed an ash tray. “No, Pam,” June told her. “I’ll find something else for you, but you may not have the ash tray.”

“Don’t be silly, June,” said Richard. “At Pam’s age, you can’t expect her to know what she can or can’t have.”

“She can learn,” said June.

“She’s too young,” said Richard.

“And you don’t want me to tell her any more?”

“No.”

A few nights later, Richard walked into his den and June heard a bellow. “June!”

She came running. He was standing in the middle of the room. At his feet were all the things that should have been on his desk. The floor was sticky with soft candy. “June,” said Richard. “You must talk with Pam. You’ve got to tell her there are things she mustn’t touch.”

“Yes, Richard,” said his wife.

It was June who tackled the problem of discipline head-on. It’s June who does it today. “June tells me I’m too soft with the kids,” says Richard. “But when I come home at night I want to play with them!”

He’s proud of the way the mother of his children has taken over. He likes it when she puts her foot down, orders him to bed when he has a cold, hovers over him like a pint-sized angel of mercy. There was no happier man on earth the time she flew to the Utah location of “The Conqueror” to be with him.

Only when June arrived was the situation well in hand. She kept their room neat as a pin. She added her feminine touch to make it more like home. She was up at 6 A.M. to prepare breakfast. When he returned evenings, the laundry was done and June was there looking as if she’d stepped out of Saks Fifth Avenue and had never seen a clothesline.

He thought about the day at the table when little Pam asked him, “Daddy, is Mother a little girl or a lady?”

He’d smiled. “Sometimes, Pamela, I really don’t know.”

Slowly but surely he was finding out. And so was June. He thought about how he had been the one who had seen June through the jitters of Pam’s arrival. When the doctor announced that they might expect Ricky, it was Richard who needed a calm, steady influence.

The baby, said the medico, would be born on January 12. June thought differently. “I’m going to give you a little boy for Christmas,” she told her husband. “And he’s going to look just like you.”

Two days before Christmas, she said, “I ache.”

Dick patted her on the head. “Wife,” he said. “You don’t know what a labor pain is. Just put your trust in my judgment.”

“Call the doctor,” said wife.

He did. “June aches,” he told the medico. “But it can’t be labor pains. I’ve been timing them.”

He began to tell how he’d been timing them, but he never finished. The doctor was shouting something about getting June to the hospital. That’s when Richard officially became a nervous wreck. “You’d have hardly known my usually cool, calm and collected husband,” says June.

“June laughed through the whole thing,” Richard says, still amazed. “Ricky was born Christmas Eve day. They’d given her something to ease the pain and make her sleepy. But the only effect it had was to wake her up.

“She never stopped talking or laughing. She came out of the delivery room grinning and waving to everyone in the hall and calling, ‘Merry Christmas!’ ”

Ricky weighed in at 4 pounds, 10 ounces and they kept him in the hospital for several weeks. When it was time for him to come home, Richard and Pam went to get him. They’d told Pam about her own adoption, how they’d gone to a big building and had chosen her especially. Now Pam was going to a big building to get her brother. There was only one thing that marred her happiness. “Ricky ought to be adoptinated,” she told them. “Please adoptinate Ricky.”

June aged a hundred years during Richard’s near-fatal illness. He hadn’t been feeling well and the doctor had put him to bed. June nursed him for three days and on the third evening fell asleep from exhaustion. She was awakened suddenly. Richard had collapsed at the foot of the bed and was moaning, “Help me, June.”

Somehow she managed to get him back into bed. She called the doctor who rushed him to the hospital. Richard, they found, was allergic to the miracle drugs that might save him. The first operation was unsuccessful. There was another.

Richard was on the critical list. June was told that it was doubtful that he would live. She waited. And she prayed. Every so often she’d rush home for a moment to see Pam and Ricky, to smile and reassure them daddy would be all right.

She was in the waiting room at the hospital when she was told, “You’d better go in.”

She walked into her husband’s room. She sat beside the bed and began to talk to him, to tell him that he must live. She had no way of knowing whether he could hear her.

She’ll never forget when he finally opened his eyes. There was a tube in his mouth and he gave her a weak smile. “This is a heck of a way to quit smoking,” he said.

“That’s when I knew he would be all right,” she smiles.

They know what it’s like to come close to losing one another. Could they voluntarily say goodbye and walk away? Could they leave their home, cold and dark and empty and blot out the memories that would haunt it? The columns make it sound a cinch.

In the summers, the Powell family increases. Richard’s daughter, Ellen, lives with them. She’s a teenager now. She was seven when they were married, and she thoroughly approved. She’d watched as her brother Norman had given the Powells a book as a wedding gift and she refused to be outdone. Disappearing for a minute, she’d returned with a hastily wrapped package. “I want to give you a book, too,” she’d said. It was “The Adventures of Superman.” Her allowance had been a bit limited, but the thought was there.

June’s brother, Arthur, has also come to live with them. He graduated magna cum laude from USC last summer and the Powells attended the ceremony as Richard puts it, “So proud our chins were practically in the clouds.”

Arthur’s the first student admitted to the new medical school at UCLA. “Now we’ll have a real family doctor,” says Richard.

As the rumors went on, the Powells began working together in “It Happened One Night.” The picture stars June. Richard is producing and directing.

Fireworks were predicted. “Anybody at M-G-M or U-I can tell you that Allyson is temperamental,” said one expert.

Proof may be found on at least one office wall at U-I studio. Thereon is tacked an elaborately printed card. The large print reads, “Allyson Obnoxious Club.”

It’s a membership card and it’s signed by the club president, June Allyson. “Just anyone can’t get in,” grins the owner proudly.

As for the temperament, June says, “Some people think others are temperamental because they’re definite.”

She had to learn to be definite. Richard helped teach her. And he drank a toast to her when she announced that she was going to take the part of the wife in “The Shrike,” despite the fact that he thought it was a mistake.

As for their working together, when the script of “It Happened One Night” was finished, they began discussing one of the scenes at home. There was a slight difference of opinion as to how it should be played. June listened as Richard described his ideas. “But . . .” she began. Then she sighed, “But who am I to tell you?”

“But I value your opinion,” he told her. “But you’re such a wonderful actor,” she told him.

Suddenly they were grinning. Instead of tossing furniture they were tossing verbal bouquets. “How could anyone think that” we could ever resign from such a mutual admiration society?” laughed June.

A ten-year membership is a long one. “It seems more like ten minutes,” says Richard, remembering.

June remembers, too. And it’s doubtful that the wife and mother who is the Mrs Powell of today will ever forget the uncertain young girl of yesterday who, as a bride, prayed “Please, God, give us a long life together.”

THE END

—BY BEVERLY OTT

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1955

No Comments