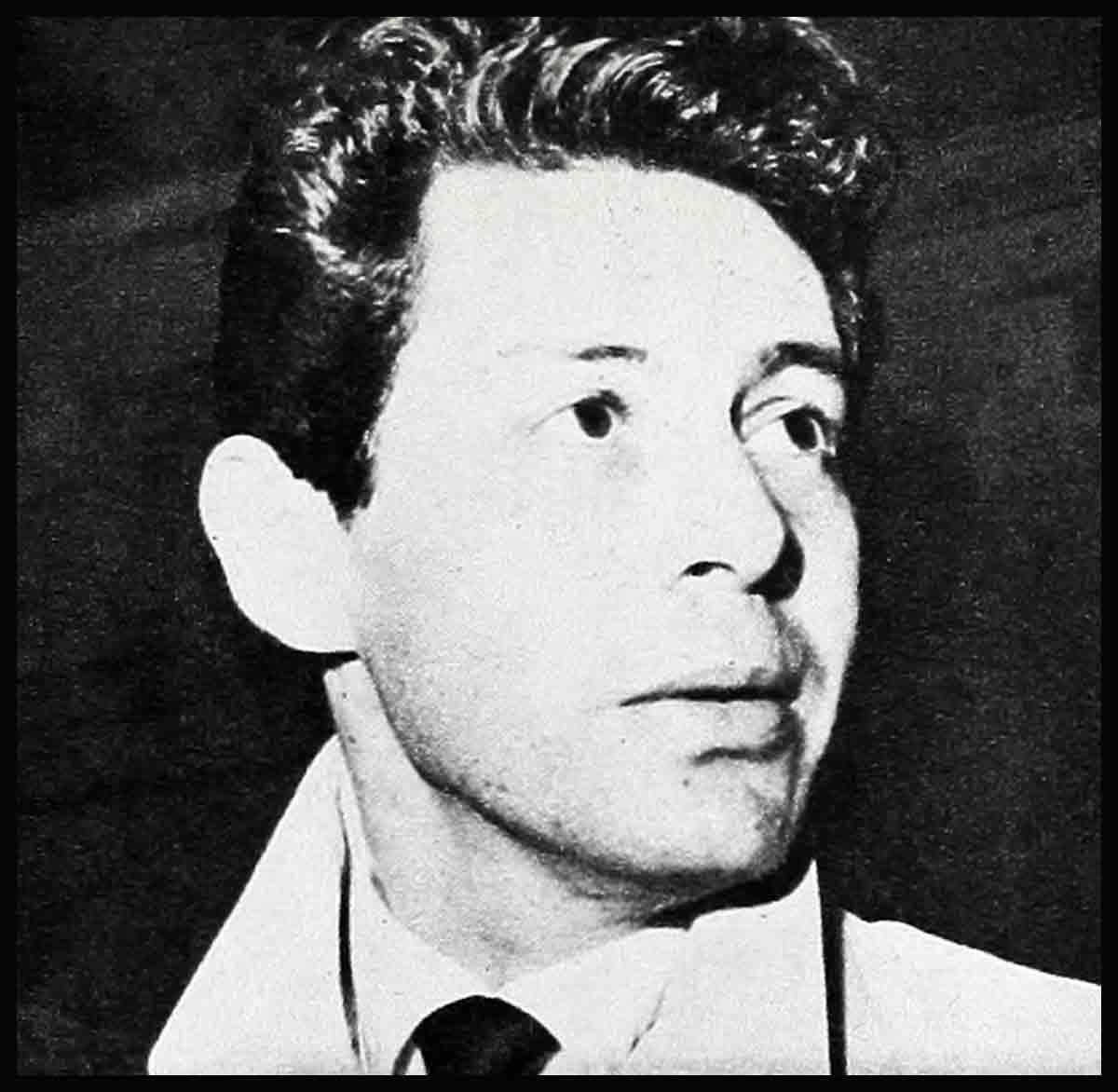

Town With Pity—Eddie Fisher

The assignment: Go to South Philadelphia—Eddie Fisher’s home town—and find out what old friends there think about his current plight. He’s being ridiculed from all sides now. The whole world seems to be laughing at him. Examples from today’s newspapers alone: Hedda Hopper wrote, “Eddie Fisher has a whole new career as a comedian. When asked if he had a new romance, he said, ‘There are lots of romances in my life—my children.’ ” Jack Gould: “On WNEW yesterday, Eddie Fisher heaped fuel on his own ridiculous image by trying to make jokes about his Roman scandal; the drab lad should simply shut up and keep listeners from suspecting he enjoys all this fascinating trash.”

Robert Sylvester: “Merv Griffin saw a film so old, Eddie Fisher got the girl!”

But what do the home-town folks think of the boy they knew “when?”

Are they laughing, too?

Or do they feel sorry for Eddie?

Or what?

The trip down

On the train from New York to Philadelphia, I read through some old notes I’d stuck in my briefcase. Specifically—an interview I had with Eddie’s mother, Kate, back in April of 1954; when Eddie was twenty-five years old. the most promising of the new crop of singers; when his recording of “Oh My Papa” was tops on everybody’s hit parade.

The interview with Kate had taken place in the living room of a nice new house Eddie had just bought for his family, on the outskirts of South Philly. I remember Kate as very happy and proud that day. Eddie had just completed an engagement at the Copacabana in New York and was up at Grossinger’s relaxing. In a few days he’d be leaving for Hollywood—his first big trip. She felt a little sorry that he had to go, she said, because Hollywood was so far away and she’d miss her son. But business was business, she said, and maybe—knock wood—he’d have good luck in that place called Hollywood. . . .

I got into a cab at Philadelphia’s Penn Station and asked the driver to take me to 2512 Fifth Street. It was the house where Eddie lived from the time he was horn. The house where he grew up.

The driver—Morris Solomon, forty-one, of Pennington Street—smiled and said, “That’s my old neighborhood. You know people there?”

I explained about the story I was doing.

Solomon started up the cab and then he shook his head and said, “Eddie Fisher. That poor guy. You know, I feel sorry for him. I really think he’s ruined his life. He was foolish. He had a good girl there in Debbie, his first wife. She would have stuck by him through that other mess. But what does he do but leave her. . . . He’s ruined. Sure, he’s still got a good voice. He sings nice. He sings good. I’m not saying he should kill himself. Far from that. But just think what a nice life he’d have had if he kept things the way they should have been kept. With such lovely children. . . . Well, Debbie’s all right now, at least.

“I have a brother-in-law, Charlie. Fourteen years ago Charlie went to California to work. He got a job in a shoe store out there. And one day he was fixing a window display and the boss of the whole chain of stores came by and complimented him on what he was doing. Charlie thought that was a nice thing for a boss to do. The boss’ name happened to be Harry Karl, the fellow Debbie’s married to today. So at least she’s got herself a nice husband there. . . . But Eddie. I don’t know. He just seems ruined to me. What kind of girl can he marry now? Where does he have left to go?”

Solomon let me off at 2512 Fifth. A tiny house, fresh-painted, two stories high, fronted by a small stone stoop, connected on either side with similar houses—a whole row of houses down the block.

I walked up the steps of 2512 and rang the front doorbell.

A pleasant woman answered and said no, she didn’t know Eddie Fisher, nor any of the Fishers; that her family had bought the house after the Fishers had moved.

“But,” she said, “the tailor across the street knew them. He’s been here about thirty-five years, on the same street. Maybe he can help you.”

The tailor

“Don’t use my name. I don’t want anybody thinking I’m saying anything for publicity. But did I know Eddie Fisher? Did I know him? I fixed for him his first pair of long pants. His mother bought him the pants for the holiday, same holiday as today, the Passover. And they came from one of those stores where you just buy the pants with no alterations—you know? Cheap, in other words. So his mother brought Eddie in here with the pants and she said to me, ‘They’re his first long ones, they’re important, so would you fix them well for him?’

“I got to know Eddie since then. He was always coming in my store, sometimes to bring stuff in for cleaning and pressing, a lot of times just to come and keep an old man like me company. And I can’t say anything hut nice about him. Try to get me to say something bad about him and see how far you’ll get. How can anybody help liking somebody who’s good to his friends and his parents? To me. that’s the mark of a good man. Ever since he was a kid, Eddie was a polite boy, a nice dresser, courteous—very courteous. He was the kind of kid if he’d be in the store here with a suit to be pressed and if somebody else came in a few seconds after, he’d always ask the other person if he was in a hurry to go first.

“He was full of favors, always doing favors for people. Even when he got to be a big star. Once he played the Latin Casino here and he invited practically the whole neighborhood over. He picked up the tabs for everybody. Me he even gave employment that week. He called me up and he said, ‘I need a tailor to come over and fix some things before I go on stage every night, so I was wondering if you could come over.’ But who was he kidding? What things did he need fixed? He had suits and tuxedos from all the finest stores in Hollywood and New York and London. The fits were perfect. So what did I do but stand there a few minutes before every performance and take a whiskbroom and dust a little lint from his jacket. But you know what he gave me for this? Ten dollars a night, plus cab fare. Every night for a week. Just because he’s a boy who’s always doing favors for people.

“About his present situation I’m not going to tell you a word I don’t know from nothing. People don’t know what it’s all about, anyway. What they read, they believe. A lot of people are idiots. They believe everything. Well, not me. I only believe Eddie Fisher is a great boy.”

Mrs. Bendroff and Sylvia

A few doors away—at 2516 Fifth Street—I rang another doorbell.

A very old woman, Mrs. Fanny Bendroff. Answered.

“Ja?” she asked softly.

When I told her about the story I was doing, her face burst into a glowing smile | and she said: “I don’t speak the English good. But I will tell you. Yes. Eddie Fisher—I just wish my grandchildren would grow to be like him. Nice. Nice. So nice boy he was. He used to sing in the synagogue sometimes. Over by Eighth Street. Near Porter Street. He would sing in the backyard. He would even sing in the street. His father—he have a pushcart sometimes—with fruit, vegetable. And Eddie would walk along with the father—only six. seven years old he was—and sing so the people would look out the window and see what the father was trying to sell. . . . Nice. Nice.

“I bear the other day he sing again for the microphone?—the gramophone?—ja, ja, the phonograph, that’s right. I hear he sing better than ever. It make me happy. But, too, it make me not happy now. I see a picture of him in newspaper, and he look like—skeleton. Too bad. I want to see him happy again. Eddie used to be happy boy. His mother, father—they poor. Sometime the other children on street—they all have nickel for ice cream in summertime. And Eddie, maybe he only have penny, for a little piece of candy. But it never make a difference—not to Eddie. He was always happy—then. Always. Nice.”

A phone call interrupted Mrs. Bendroff.

When she returned to the door she said. “My daughter Sylvia. She calls to wish us the Happy Passover. And I tell her about you. And she would like. too. to say something about Eddie.”

Said Sylvia: “I just wanted to tell you—I liked Eddie when we were kids. And I still do. As a kid he was the finest type—not a snip, not fresh, like some other kids in the neighborhood. And even after he grew up and had his success, he was still the same good person. I remember once—not too long ago, in fact—I was visiting my mother and we were walking down Fifth Street. And this big black chauffeur-driven limousine pulls up alongside us and stops, and Eddie Fisher leans out smiling and asks how we both were. He happened to be in Philadelphia on business, I know. He happened at that minute to be on his way somewhere. But he took time out to stop and talk to us. And I thought this was very kind of him. . . . It’s too bad he’s all mixed up in this divorce business with Liz Taylor today, that his name is all over the papers, that they make the remarks about him they’re making. He’s a sweet kid.

“By the way,” Sylvia went on to say, “you might want to talk to my brother Al about Eddie. Al’s just a few years older than Eddie and I guess you could say he knew him better than just about anybody in the old neighborhood. I’ll give you his phone number. I know he’s not home now. But why don’t you give him a ring later this afternoon?”

I thanked Sylvia for the information.

I left the Bendroff house and, canvassing the neighborhood. I talked to several other people who had known Eddie Fisher back in the old days:

Ada Shifrin, who with her husband Martin runs a general merchandise and check-cashing store on the corner of Fifth and Shunk Streets.

A woman druggist (who prefers to remain anonymous).

Seymour Wald, seventeen, who works in a shoe repair store on the corner of Fifth and Porter.

An elderly woman and old neighbor of the Fishers, Mrs. Anna Spector.

And a gentle and kind-faced man, a rabbi, named Pupka. . . .

Ada Shifrin

“I think Eddie—poor kid—got in the situation he’s in because he’s too good, too chicken-hearted. He’s the most faithful guy you want to know. I hear that was part of the trouble about his marriage to Debbie Reynolds—that nice as she’s supposed to be. she didn’t like his old friends hanging around so much, and Eddie wasn’t the kind of guy to kick old friends out. Oh. he’s faithful to people he loves.

“And such an easy touch. Like the reason he married Liz. She’s a good actress, after all. She played on his sympathy after Mike Todd was killed. She’s gorgeous. No wonder she got him . . . But right or wrong in that, don’t let anybody ever tell you Eddie’s anything but good. He’s helped people all along the way, ever since he made his first cent. He still sends bis father $125 a month. He loves his family and he helps them all—and that includes six brothers and sisters. All the actors and singers you read about should be so good to their families. I know Eddie from the time his kid brother Bunny used to work for us, when Martin and I had our luncheonette. I remember Eddie’s manners, even when he played something like a pin-ball machine. Other kids get all excited and start shouting all kinds of things—but he never lost bis manners.

“Now he’s still polite. He doesn’t want to hurt other people, so he never gives his side of the story in the papers. He doesn’t like to say no, so he says yes to everything : ‘Yes, I’ll marry you’ . . . ‘Yes, I’ll go away’ . . . ‘Yes, yes, yes.’

“Well, it’s too bad he’s got bad luck in his love life. But he’s got enough else on the ball to make him overcome any bad luck he might be having now. . . . Why, do you know that when he was just getting started singing and playing a date at the Vie En Rose nightclub in New York, he sent an invitation to me and Martin to come up for an evening and be his guests? The entire evening—free—on him. How’s that for faithfulness to old friends? Any wonder that the people down here remember him? And are crazy about him?”

The woman druggist:

“I have nothing but the highest and finest to say of the entire Fisher family—especially Eddie. He was a good-living Jewish boy. I can still see the little tyke walking by my store with his fiddle case in his hand, going for his lessons. Such a quiet boy, he couldn’t speak loud. A mama’s boy. Mrs. Fisher would come in to buy a card for someone’s birthday or anniversary, and the way Eddie’d hold her hand and look up at her—a mama’s boy!

“Poor Eddie, I feel sorry for him today. He’s too unsophisticated to play the role he’s been forced to play. I feel sorry for Debbie Reynolds, too, and the way their marriage ended. And for Liz Taylor, too. Yes, I even feel sorry for her. I don’t think she’s a bad woman. I just think she’s used bad judgment.

“But most of all I feel sorry for Eddie. Oh, how could a boy like he is stand such a shock, to be told he was no longer wanted, to get out? A mama’s boy like that. They say, well, he did the same thing to Debbie Reynolds, now someone did it to him. Well, such is life, I imagine. And now I just wish Eddie would forget everything and begin to sing again. I imagine he wants a comeback. God grant it.”

Others speak

Seymour Wald: “I first met Eddie through his sister Arleen. Arleen and I were just babies then. And one day we were playing with a ball. And the ball went rolling out into the street. I ran after it. A car came by and hit me. And it was Eddie who came running out of the house to take care of me while we waited for the ambulance to take me to the hospital.

“The last time I saw him was a couple of years ago. He was married to Debbie Reynolds then, and he brought her here to Philly to show her his old neighborhood. They spent the whole day talking to people. And then, at one point, they sneaked off to a little cafeteria a few blocks away. To have a cup of coffee. Well, a few of the kids followed them to the cafeteria. I happened to be walking by to see what was happening. I looked in the window and saw Eddie sitting there. He looked very tired. But when he saw me he smiled and called me inside. And introduced me to his wife. And bought me a cup of coffee.

“And when you ask me what do I think about Eddie Fisher today—I just think that he’s a guy who was very nice to me. Twice. And that’s enough for me.”

Mrs. Anna Spector: “He was not really a success yet. But we were hearing his records on the radio. He was beginning to get places, so to speak. And this one day I was standing in the Hopkin Candy Store, down the street. Eddie walked in. I began to joke with him. I said, ‘Well, now that you’re getting so famous I guess we’ll never hear a song from you again without having to pay—no?’ And do you know what he did? Right there in the candy store he sang three songs. For me. And I thought, ‘This boy will always come out on top—because he’s a good boy.’ ”

Rabbi Pupka: “I am sorry that I cannot give you too much time. But today is our Passover and I am very busy. But yes, I will tell you what I know—or knew—of Eddie Fisher. He came to our synagogue—not often, but once in a while. He sang for us at social functions from time to p time. His favorite song, I recall, was ‘The Donkey Serenade,’ very popular at the time. He sang it well, very well indeed.

“His present situation today? I don’t know much about it, except that he was sick for a while, and I am sorry about that. The other matters? I know only that with faith, Eddie Fisher will overcome all obstacles. With faith. . . .”

The final interview

Late that afternoon, as I’d told his sister Sylvia I would do, I phoned Al Bendroif, an old friend of Eddie’s, who said: “I knew Eddie when we were kids. And I knew a lot about music, too. I used to feel sorry for him when I’d hear him singing—he had a swell voice, but no vibrato. So one day I called him into my house. I said to him, ‘Eddie, I’m going to teach you vibrato.’ Then I placed my fingers at the base of his throat, told him to sing, shook my fingers around till he got the idea finally—the vibrato.

“Well, I went into the Army in the early ’40s. And when I came home in ’46 my mother told me that Eddie was singing in New York. I felt good for him. I always knew he would make it, and I knew that he was beginning the big climb. At the Navy Yard, in fact, where I work, I began telling people, ‘Listen to Fisher.’ They didn’t know who I was talking about at first. But they soon found out.

“Anyway, more important, I began writing songs at about this time, a field of work I am still trying to break into. Well, one day back then, I found out that Eddie’s mother was going to New York to visit him and I sent along two of my tunes, for him to look at. A few weeks later I went to New York myself, to see Eddie. I asked him about my tunes. I wanted no favors. And Eddie was doing no favors. In answer to my question he said, ‘I can’t do just any tune, Al. They want me to do tunes from movies, shows. You know how it is.’ Naturally, I was disappointed. But I had a new tune with me, which I call ‘The Girl from Rio.’ So I asked Eddie to at least look it over, and he said he would, he’d be very glad to.

“A couple of months later I went to hear Eddie at a place called Chubby’s, over in Jersey. As soon as I walked into the club and Eddie saw me, he shouted over the p.a., ‘Al, I love that tune!’ Needless to say I was pleased, delighted. After the show, I asked Eddie if he knew anyone who might be interested in the tune. He said, ‘I am.’ He told me to call him a few days later. I did. And Eddie said, ‘I love your music, Al. And I’m going to team you up with Jerry Ross. He’s in ASCAP, so you know what this means. You’ll be made.’ Eddie added that I should send anything else I wrote to his suite at the Essex House in New York.

“Well, probably someone threw a monkey wrench into the works. I waited. Nothing happened. And not too long afterwards, Eddie’s parents told me he was going into the service. And I knew, as far as I was concerned, that he had other things on his mind now, and that this was the end of our relationship. . . . I’d talked to Eddie a few times those last weeks. I could see that the pressures of his work were changing him.

“I remember his father came home from New York once. He was sitting outside and when I asked him how Eddie was, Mr. Fisher said, ‘I’m very upset about him. He forgets a lot of things now. They’re loading too much on him.’ . . . So, as I said, that was the end of my relationship with Eddie Fisher. I guess you might guess that I feel some resentment towards him, for having helped him once and for his not really having helped me in return. But actually I don’t feel resentment. On one hand—as far as my tunes go—I feel I’ll get my break someday. And on the other hand, no matter what happened between us, I can’t help remembering that as a kid Eddie was as terrific as they come—and after all, that phase of knowing him was as much a part of my life as any other.

“Yes, I feel sorry for him. You see, he was never an extrovert. Excepting in his pushing to be a singer. But otherwise he was very quiet, a real introvert. And I feel that from the moment he entered the big time he got involved with people who found it easy to sway him, and that he was more or less easily influenced in everything that followed in his life.”

The trip back

My day in Philadelphia was over, It was evening now. I was back on the train again, heading for New York. I read a newspaper. I smoked a cigarette. For a while, I looked over the notes I had taken I that day.

And then, once more, I found myself looking back at those April, 1954 notes—that interview with Eddie’s mother, Kate, eight long years ago.

I read a little here: “He once told me, ‘Mama, if I can’t be a singer when I grow up, I’m going to be a street cleaner. I don’t want to be anything in the middle. . . .’ ”

A little there: “Eddie’s favorite dish is lima beans in chicken soup with noodles. Lots of noodles. . . .”

A little more here.

A little more there.

And then I read this quote from Eddie’s mother, the final page of my notes:

“Not too long ago I had a talk with Eddie. It was a sort of mother-to-son talk, I guess you might say. What I asked him was, ‘Eddie, when are you going to get married?’ I told him that he was twenty-five now, that he had made his name, that in a way he had everything he wanted. ‘You have everything you want,’ I told him, ‘except a wife. And a wife, Eddie, that’s something I think you should start looking for now.’ And you know what else I told him? I said, ‘You know, Eddie, it’s none of my business, and I don’t really know the kind of girls you go out with, the kind of girl you might end up marrying. But the kind of girl I’d like to see you marry. Eddie, is a nice little poor girl, a girl who’s never had anything before, a girl you can give things to, show things to, things that will be new to her, that will make her the happiest girl in the world. Not a rich girl, a spoiled girl—the kind if you take to Florida, she’ll tell you about the hotel she stayed in the last time she was there. Not a rich girl like that. But better a poor girl who’s never been to Florida before, who’ll get a big thrill when you take her. when you show her something new and beautiful like Florida.’

“And do you know what my Sonny Boy said to me after I told him this? He said, ‘Mama, that’s just the kind of girl I’d like to find someday. I just hope I do. . . .’ ”

—BY ED DEBLASIO

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1962

zoritoler imol

31 Temmuz 2023I like this post, enjoyed this one appreciate it for putting up.