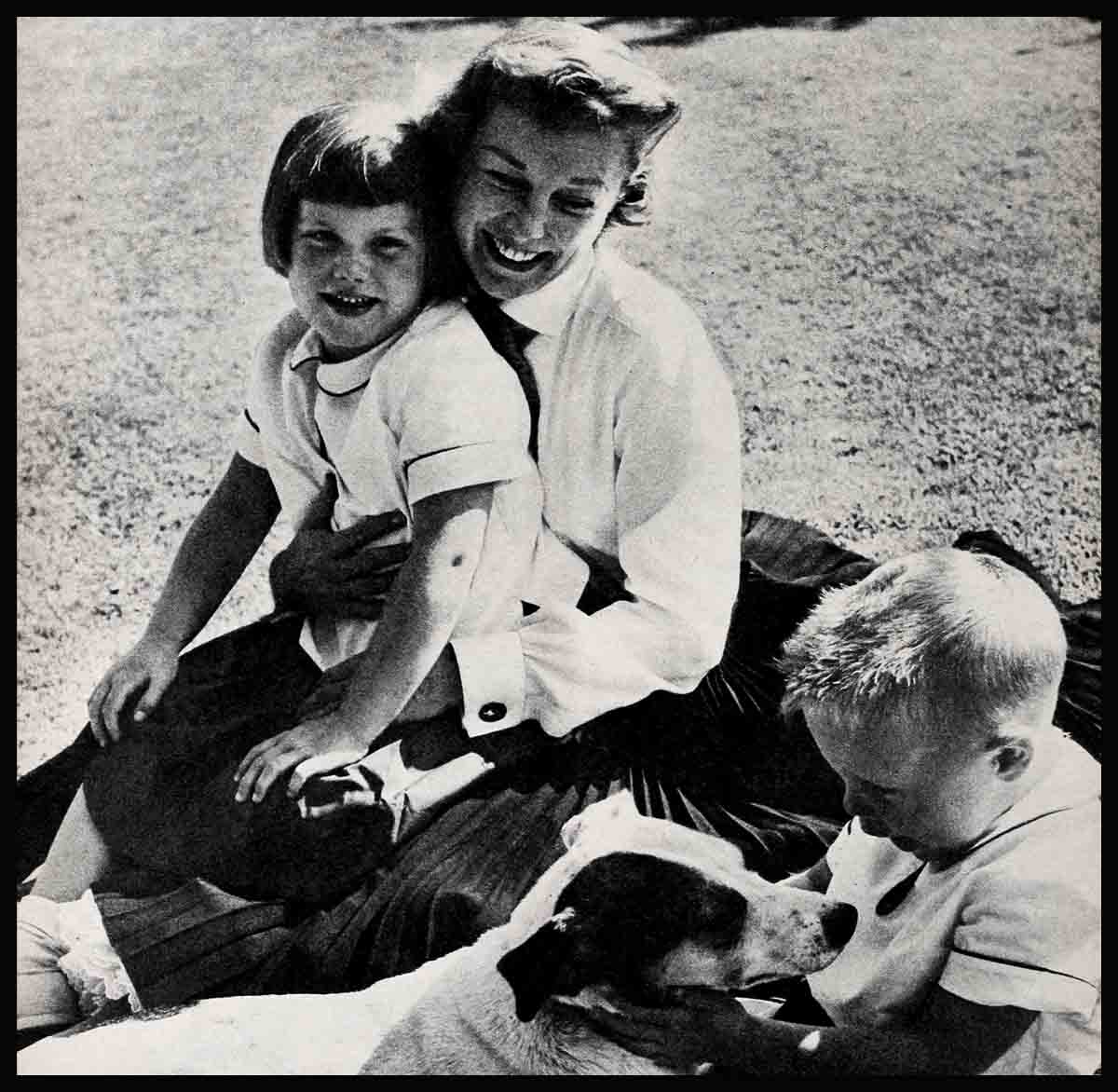

Mother’s Little Dividends—June Allyson

When I consider what we actually have done for our two children—gentle, determined, thoughtful Pamela, now six, and laughing, life-of-the-party Ricky, nearly four—I’m filled with wonder at how little it really is. Just a warm, clean room, a place to sleep, food and music, cuddling and love, acceptance. We give them clothes and toys for play. We try to answer their never-ceasing questions about the strange world surrounding them. We teach them about God and His infinite goodness. A nurse looks after them while I’m away at work. A doctor visits them when they need medical care. But what does this really add up to?—so very little in contrast to what they give back to Dick and me.

Even as tiny, helpless babies who just looked at me and smiled, they have enriched me with faith and tolerance and patience and a growing maturity. They gave me the most precious gift of motherhood—and with it fulfillment and completion as a woman. They have strengthened an already good marriage. They have given me inner contentment and happiness and the boon of relaxation. They’ve opened my eyes to a new realization of the meaning of Christmas and birthdays. They gladden my heart daily. No queen ever had a more loving entourage.

I confess freely that I’m an incurable sentimentalist where children are concerned: the kind of mother who even ape-records her children’s Christmas prayers! And though our marriage ceremony was simple and unostentatious, when it came to the children’s christenings, you’d have thought I had delusions of grandeur.

Not long ago a woman who expected her first child within four months complained, “I’m bored with this whole project by now. I’ll be glad to get it over.” And I felt myself stiffen with momentary anger.

As for myself, I wanted a child with all my heart—and for years. When my doctor told me that I probably couldn’t have a baby, I was so full of tears you could have flooded a battleship with them.

Try as I would, I couldn’t set my thinking right about this bitter personal disappointment. I’ve had disappointments before—plenty of them—including a long hospital siege with a broken back, but I found myself thinking over and over—“Why am I denied a child?”

Finally, I asked Richard how he felt about adopting a baby. “I’ve just got to have a baby,” I said. “I can’t wait.” At first he demurred a little, saying I was so young and had so many career problems ahead. Then, a little later, he agreed. And our name went on the waiting list. Immediately, I was a changed person. I could study the wonderful family pictures in the magazines, attend baby showers and be contented. For I, too, was going to have a baby!

And when little Pamela cooed in my arms, it was love at first sight. I couldn’t even wait until she was a year old, so I gave her a six-months’ birthday party. And when she said “Ma-ma” and “Da-da” at only ten months and walked a month later, I considered her a genius and became very tiresome with our friends. In fact, with both children, I’ve had to restrain myself from saying to Richard, “Call Hedda Hopper, quick” at each new manifestation of their remarkable skills.

I wanted to start very early to familiarize Pammy with the word adopted long before she could understand its meaning. Love is the greatest bond between parent and child. And the adopted baby fills an emotional vacuum and thus is the recipient of much pent-up affection. Knowing that she was confident of our love, I explained to her, from time to time, that God had meant her for us and we had brought her home and adopted her. I pointed out that we had wanted a baby girl just like her for a long time and that we were so happy to have her.

And then, five years after our marriage, I knew I was to have a baby. And I realized again that “All things work together for good, to them that love God.” The miracle filled us with joy.

But there was one tiny misgiving. How would I explain to Pammy so that no question of rivalry between the children would arise? As it turned out, I had no cause for worry. I explained to her that I was carrying the baby because I didn’t want to leave her to go find a baby brother or sister for her. She was deeply content. As it happened, Ricky was an incubator baby and I left the hospital a week before he was ready to come home.

So Richard and Pam went to the hospital to bring him home. “See, Mommy,” explained Pam, “we had to go to get our baby, just as you had to go get me. Now he’s adoptinated just like me.” And when Ricky is older I’ll explain to them both that although they grew nine months in different mothers, they were born the same way and now have the same mother. and father who love them alike as members of one family.

After Ricky joined the family, Richard and I decided that when friends came to see the new baby we’d first visit with Pam and then ask her if she wouldn’t like to show her little brother. The first time Pam proudly led the way to the nursery. But the second visitor hardly entered before Pam was asking if she wouldn’t like to see the baby. A little foresight took care of any evidences of jealousy.

Always I’ve had to work things out concerning the children in my own way. Some mothers find their solutions in child psychology books. As for me, I know that deep down within my heart I’ll find the answers. If I followed a book it would only mean doing things by rote, not by my instincts. I think we can find truth just in ordinary living. And that’s why thoughtful mothers have hunches: “It seems to me that Johnny does better when . . .” or “One thing I’ve noticed about Mary when she’s with strange children . . .” And we don’t need child study to live by such rules as “Love thy neighbor as thyself” or to discover that “You can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.” Such rules were made long before the books.

Not long ago, Pam, a determined little miss, was deliberately naughty while a friend was over. I said to her: “Mommy loves you, Pammy, no matter what you do. But she doesn’t think your actions are very lovable at this moment.” And I explained why those actions were harmful in their effect. I knew I had to stop her but my main concern was with making up after the incident was over. Later, my friend, who had studied psychology, explained, out of Pam’s hearing. “You handled that very well, June. You made Pam see that it was what she did and not she herself that you didn’t approve of.”

“But that seems the only natural way to me.”

“Some mothers would say, ‘You were a bad little girl and Mother doesn’t love you. Mother couldn’t love such a mean, nasty child. If you do it again, I’ll give you away!’ ”

Of course, there must be discipline and punishments. Though I’m deeply sentimental about children and would spare them any pain, I feel instinctively that we must draw the line when we sense that children want us to. I know that Pam and Ricky want limits. They’re struggling to take on the ways our world considers right. And I want to bolster their efforts with warnings of what conduct is off limits.

I believe Pam and Ricky understand that discipline is a sign that we care. Youngsters have to feel that from us, or they have no reason for wanting to be good. Take away love and you take away the surest guarantee that a child will attempt to work through his problems, whatever they may be.

As far as I’m concerned children can be children. If that means noise, occasional freshness or giggling or shouting or bouncing, that is all right with me. But I draw the line always and without hesitation when Pammy or Ricky endanger themselves, if they should mistreat playmates or animals, when they are unnecessarily destroying property. And sometimes when I simply cannot stand what they are doing! I try not to be capricious, approving something today and getting all upset about it tomorrow. But I’m not ashamed of being human. After all, children have to live with humans.

And I believe that punishment should be effective. When I told Ricky to sit in a chair as punishment, I saw that he was having a good time, rocking back and forth and not in the least realizing why he was there. If I sent Pam to her room, she began to color in her painting books, to sing to herself, to have a fine time. So I just reversed the discipline—Ricky was sent to his room, Pam told to sit on a chair. And they understood then that certain actions bring certain effects.

Sometimes it happens that our children become teachers—and we learn from them. Pammy is attending a Catholic girls’ school, Marymount (And need I explain to any mother that filling out a school application for her brought tears to my eyes at how fast time was flying?). For years she’d been saying her prayers as I had been taught to say them. So one night shortly after she started school when I was hearing her prayers, she completed the Lord’s Prayer with “And lead us not into temptation: but deliver us from evil. Amen.” And then stopped. “Go on, dear,” I said, “you haven’t finished.” And I began to prompt her: “For thine is the kingdom and—”

“I’ve finished,” said Pam. “That’s the way we say it in school.” I had a slight sense of shock. After all, I thought, does one tamper with the hallowed form of a prayer? But I considered and told her, “All right, darling,” and then listened to the string of “God blesses” which Pam—and Ricky, too, tack on so that it will keep them up longer and require my continued presence. “. . . and God bless the trees and the tractor and my skates and my bicycle and the well and the new pump and Daddy’s new tools in the workshop . . .”

The next night Pam asked me to say the prayer. I did, using her school form. “Go on, Mommy,” she said. “Say the ending like you always do. I’ll say it my way and you say it your way.”

A fine lesson in tolerance. Like all parents, I’ve wondered how best to introduce my children to God. How much do they understand when I attempted to answer their questions? Will it help them if I explain those times in my own life when hope and love and faith convinced me that He was near? Not long ago Ricky asked, “Who makes puppies?” and I answered, “God.” “Yes,” he said. “Just like Daddy makes things in his workshop.” So I know that the children will make their own interpretations of what they see and hear, interpretations that make sense in their little worlds.

Although Pam is attending a Catholic school, she will soon start Sunday school at an Episcopalian church. My friends feel this might confuse her; I feel that it is immaterial where she learns to “Lift up thine eyes to the hills from whence cometh all strength.”

Pam loves to play records and to listen to songs on the radio. One night, she said, “Oh, Mommy, I heard the most wonderful song and I’d love to have the record.”

“Fine, dear, what’s the name of it?”

“The name? I don’t know.”

“Well,” I asked, “who sang it?”

“It’s somebody you know, but I can’t remember his name.”

“But what was the song about?”

“It’s—it’s something like a prayer.”

Armed with this confusing information I relayed it to the clerk at a record shop. And with no more ado, she brought out Frankie Laine’s “I Believe.”

“Oh, no,” I told her, “it can’t be that. It must be a child’s song. She’s only five.”

But anyway, I took it home and it was the song. And the line Pammy particularly loved was “Every time I hear a newborn baby cry” because it reminded her of Ricky when he was a baby!

The ways of children are indeed inscrutable. They may say, as Pammy does, “simple city” in her prayers instead of simplicity or, as one child I heard of who named his Teddy bear “Gladly.” “That’s a funny name,” commented his mother. “Oh, no,” said the tot, “all bears must be named Gladly. In Sunday school we sing “Gladly my cross-eyed bear!” As you’ve guessed, this is “Gladly, my cross Id bear.”

It brings a lump to your throat to think how much there is for children to learn. They are new to this world; we are the senior citizens. Actually, we are their world. Can you blame me then if, when my contract at M-G-M expired, I seriously considered giving up my work and staying home with my children? Everyone was aghast at the idea. It’s true that I was extremely career-minded, filled to the brim with biting ambition when I started in pictures. If a part I wanted desperately was given to another, I was sunk in the depths for weeks, thinking there was nothing left for me any more.

But the years passed and my sense of values changed. Today, no career problem can effect me so deeply. Today, only my husband and my children are the source of my real happiness. And, after considering the number of actress-mothers who are doing a fine job at home and the studio too, I decided to continue making pictures. Now and then, something happens at home which shows me that children don’t need as much guidance as we suppose.

For instance, Ricky is a ball of fire, always on the go, bubbling over and inclined to show off while Pammy is quietly taking everything in on the sidelines. When guests come, Ricky goes right into his act, monopolizing the conversation, showing his tricks. Pam sits by, quietly watching. And in about ten minutes she usually decides that her brother has had the stage long enough and she goes over to the guest, sits down and begins to talk in a most interesting way of her school, her playmates, her activities and soon the guest’s attention is diverted from Ricky, and Pammy gets in her innings. She could vie with him in a continuous bid for attention—but that bright little miss knows a better way (You will bear with me while I boast just a little—won’t you?).

It seems to me that many working mothers worry themselves needlessly about the time they’re apart from their children. As for me, I believe that an hour spent teaching Pam to square dance or skate; daily story-telling or watching Ricky build something; a Sunday-afternoon ride with Pammy and me on bicycles and Ricky proudly wheeling his birthday gift tractor; a long hike to see our chickens, with frequent stops to observe the wonders of nature, such as an intricately woven spider’s web or a shiny darting lizard—these are enough to keep our youngsters secure in the knowledge that they are loved. There has always been a nurse, but the children knew from the first that, although she might care for their physical needs, it is their parents to whom they turn. We show them we’re with them every step of the way. We enjoy them—relax and have good times together.

Maybe I feel so strongly about this need for a secure childhood because my father and mother separated when I was six months old. My father took my brother, and I lived alternately with my grand-parents and with my mother when she could afford a place of our own. Later she remarried and I had a stepbrother. And at fifteen I began to earn my living. Might all this make me desire to coddle the children? I hope not.

Most parents are annoyed at the early rising of their youngsters, but Richard and I love it because we have to get up early when we’re working. So we all breakfast together at 6:30. It’s a long day until we return at 7 or so for a brief playtime before we tuck them in for the night. Even though Van Johnson once described my froggy voice as “your million-dollar cold” I’m afraid it leaves something to be de- sired for lullaby singing purposes. Though I’ve earned my living singing and dancing, the first time I started singing a lullaby to Pammy she looked up at me quizzically and said, “Oh, Mommy, a lady with the pur-ti-est voice, real soft like, on the radio. Peggy Lee, she was. It makes my face feel all softlike, just like when Daddy sings to me.”

So, even if I don’t measure up in that department, I try with Richard’s help, to keep the children from distorted values because their parents are in the spotlight.

Not long ago, the nuns at Pam’s school asked me if I’d model at a fashion show. I accepted gladly. A little classmate of Pammy’s came rushing up to me. “Aren’t you June Allyson—the fam-u-us movie star?” she asked, wide-eyed. Before I could answer Pam spoke up sharply. “She ain’t, either—she’s my Mommy!” And I even forgot to correct her English.

Because mine was a poverty-stricken childhood in the shadows of the rumbling Third Avenue El in New York, I confess that I wanted to give the children twelve of everything. One Christmas Eve, for instance, filled to overflowing with warmth and happiness and the Godlike glow of that heavenly day, I piled the space under the lighted tree with a fantastic array of beautifully packaged gifts for the children—ours and those sent by our many dear friends. A sort of hush over my heart, I stood looking at the fairyland scene as darkness was falling. Richard came in and I expected him to be as thrilled as I. “Sweetheart,” he said, “this is all wrong. No children should have all these presents. Let’s leave a few; put some away for special occasions during the year and send all the others to children’s hospitals, orphanages and adoption societies where there may be no gifts at all!” As usual, Richard was right, and that’s been the pattern for Christmas ever since.

Once I stood by Ricky’s crib, watching him, relaxed and at peace, trying to stretch his toes and stuff them into his mouth and I thought, “Look, he has a built-in toy. He needs so little to keep him amused.” And on his first birthday party the crinkly cellophane and the colored ribbons from his gifts were much more wondrous than the toys. As I watch Rickey and Pammy at play—cutting out paper animals, building fabulous contraptions, painstakingly coloring with crayons, I marvel at their tremendous intentness and concentration. No wonder, I say to myself, they rebel so when lunchtime or naptime rolls around. I, too, have this childlike concentration. You can always tell what picture I’m in by watching me. If it’s a comedy I go around making what I fondly hope are gags; if a musical I’ll dance instead of walk; if I’m portraying a doctor I’m a crisp Dr. Allyson, day and night.

And that reminds me how worried I used to be about my health—hypochondriac June, they called me. My medicine chest was a forest of bottles and pills. I’d rush to the doctor with every little ailment and imagined symptom. But my children helped me overcome such anxiety. Because children rely on you so completely and because you’re so busy taking care of them and a household, you simply haven’t time to be concerned about yourself. That’s the best remedy for too much self-concern—motherhood. Of course, everyone knows that getting interested in someone—or something—is the best remedy for grief, for shyness and loneliness.

But when I suddenly needed to get rid of my appendix, I had to go to the hospital. It didn’t frighten the children because Richard was with them. And when he became so dreadfully ill (our darkest hour), I was with them. I found the strength through prayer to bear up during those nightmare days when his life hung in the balance; when he underwent two emergency operations and even when he felt he wouldn’t make it. I just had to bear up—for the children’s sake. It was difficult but I kept my fear from showing. And I think I succeeded because, when Richard was brought home, pale and weak, Pammy stood by his bed, took his hand in hers and said softly, “You been sick, Daddy?” Richard grinned. “I know you wouldn’t want to stay in that old hospital because it’s much better here at home. This is the best place in the whole world.”

So—is it any wonder that I can’t keep the glow out of my face when I see our children—or any children? I’m consumed with excitement and curiosity as I observe each new step in their growth. Right now Pam is listening to news commentators and asking intelligent questions. A year ago Ricky spoke only two words, “India” and “Balboa.” Where he got them I never knew. Today he goes on like a magpie. I know they are eager to do more, anxious to be big, excited to find out, thrilled when they’ve mastered right or left or stopping short on a tricycle. And I hope I’ll never lose my interest and eagerness to help them grow along the way. Even when, some decades later, suitably attired in a matron’s chiffon dress and fluffy hat, I’ll happily attend two lovely June garden weddings!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955