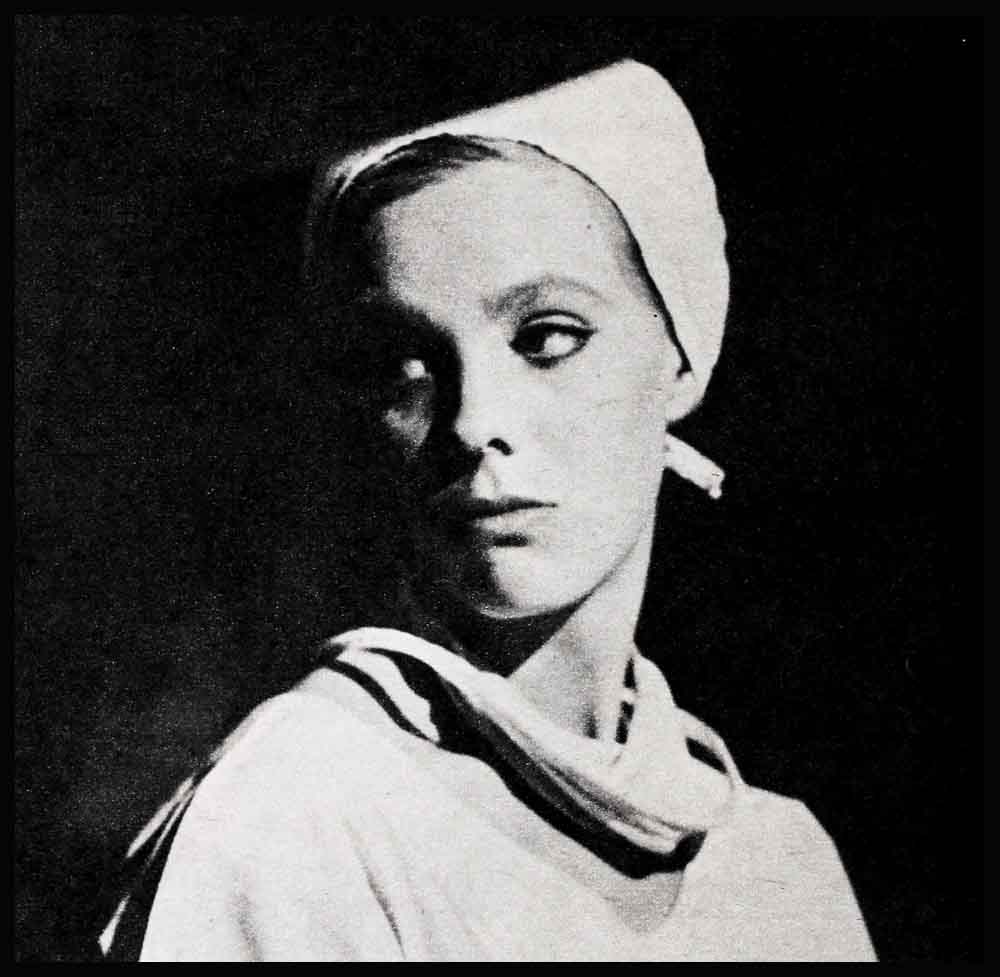

Introducing Zina Bethune

The time was late last January, a few weeks before Zina Bethune’s actual birthday. The place: the still photography room at studio publicity. The occasion: a party, a make-believe little birthday party, a strange little party.

Oh, there was a cake all right—real and pink and pretty. There were candles. There was a guest of honor, the birthday girl herself—Zina (who plays Gail Lucas on TV’s “The Nurses”). But there were no other guests present; no one except the photographer who was about to record this little scene, and he was hardly a guest.

“Okay, Zina,” said the photographer, after he set up the scene, “—I want you to smile, now.” Zina did as she was told, she smiled prettily.

“Okay, Honey, no w get ready to blow out the candles—blow ’em nice and hard.”

She took a very deep breath.

“Okay—” the photographer started once more but then there was a popping noise from some- where, loud and sharp, and the photographer shook his head and said, “I figured that light was about to go. Relax for a few minutes, Honey, while I get another bulb for this shot.”

And Zina let out the breath she’d been storing.

And she laughed a little as she watched two of the candles, teased by the breath, blow out.

And then, to pass the time, she counted the candles—“eighteen, correct!” She stared down at the candles, wondered what she should think about next and so continue to pass the time.

And. after a while, she found herself thinking about the years they represented, the seventeen years just ending . . . and about the things and the events and the people she remembered most in connection with all those years of her life.

She remembered. first, her father . . . “I treasure many things,” she thought. ‘‘But most of all I treasure the memories of my earliest childhood. Because that was when I knew my father. Because he was still alive then. I was only five years old when he died. I was too young to know about leukemia. I was too young to think that a parent could ever leave you.

“I can honestly say that my father is the only person I even remember in those first five years of my life. People who knew him have said to me since. ‘He was a wonderful human being.’ They tell about his spirit. his verve. his interest in every facet of life, his restlessness. They tell me how he was a jack of all trades—an interior designer by profession, but a man who tackled many jobs and left them at will. There is, in fact, one friend of the family who, everytime he gets disgusted with whatever he’s doing, swears, ‘I’m going to do what Bill Bethune did: quit, and seek out something more fulfilling.’ Yes, they still talk about my father. And they tell me many stories about him. I’m grateful for this, because it helps —in a way—to keep him alive for me. But my own most personal memory of him is not a story really. It has no plot, I mean; no beginning, no ending. It is, rather, a picture. Of the two of us out in the backyard one winter’s day. With him making a snowman for me. I stood watching. And he was there creating something—for me, his little girl.”

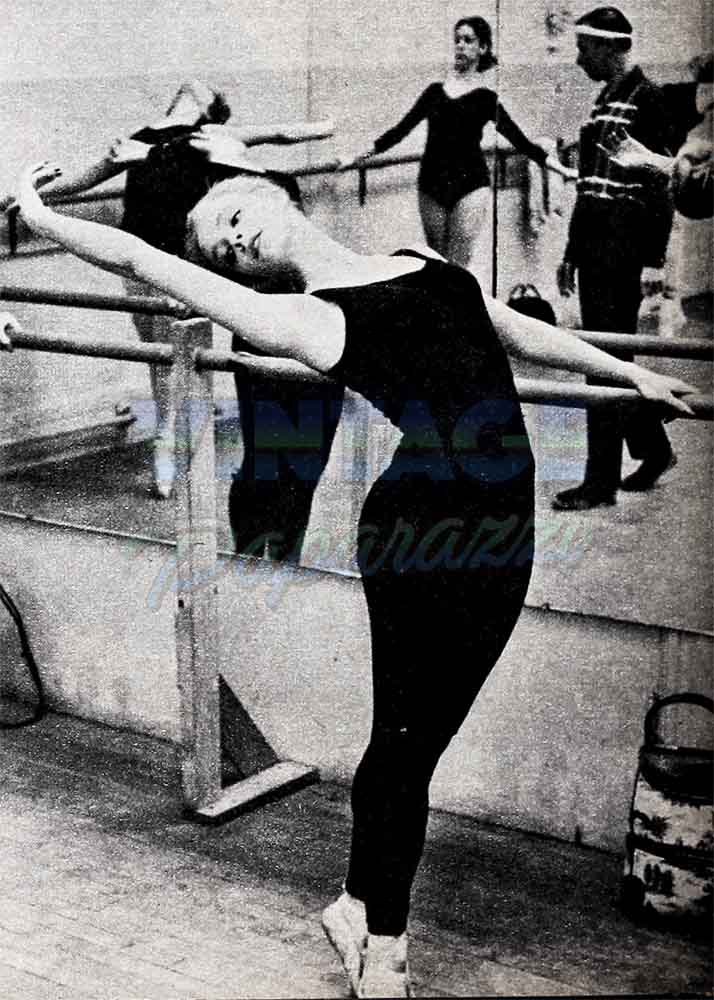

Zina remembered next the years after his death. . . . “Things were tough for us,” she thought, “—for my mother and me. We had many things to cope with and adjust to. And we had many responsibilities between us. There was the responsibility of earning money, for one thing. New York is not a cheap city to live in, under any circumstances. And it certainly wasn’t cheap for us back then. And I had a dream to one day go to ballet school. and I knew that this would cost money. too. It’s strange how, even back then, I knew how important dancing would be to me. I love to dance. I dance all the time. When people try to get hold of me and can’t, they just figure, ‘Well, she’s over at her dancing school again.’ I have to dance. I have to. When I go without it for any period of time, I’m a mess. I seem to lose some kind of balance. The world doesn’t seem to be as beautiful a place. And then, when I’m dancing again, finally, the whole thing focuses—just right—and everything seems just fine.

Back then, like my mother, I became an actress. I was very, very young when I started. Only six years old and this high. I played the little girl in something called ‘Monday’s Heroes,’ down in Greenwich Village. Fortunately, everyone said I was good in the play. Because I was i offered other roles after that.

It was an odd life, I guess, for a little girl. Because you’re expected to be very disciplined, and this isn’t particularly easy, not at first. And you don’t go to school with any real regularity, you have tutors instead. And you are alone with your books a lot of the time instead of being with other kids. No matter how hard I study, how much I read, I’ll always regret not having a real diploma.

“Yet—I had advantages, even back then. I had the advantage of having to deal with so many people, young and old, so that I have never become conscious of age as age; I mean, I have friends anywhere from eleven to sixty and I don’t think of people as ages, but as people. And I had the advantage of having a wonderful mother, who was never a stage mama, thank goodness. I had the luck of working with some fine people who helped teach me my craft. But the best of all, I was able to get enough jobs so that we could afford the one thing I’d always dreamed of—my dancing lessons. And when I was barely eight years old I was accepted for training at George Balanchine’s School of American Ballet. And I was the happiest eight-year-old ever.”

She remembered next the very special friends of her childhood, her links with a more “normal” way of life than the theater, modeling, even dancing school. . . .

“There was that boy on the block. I was crazy about him. He was eleven and I was nine. We barely spoke, but we were always looking over at one another. And then one day, suddenly, he moved away. And that was that; the end of my first great love. . . . There was Jackie Rosett, who is still one of my very best friends; my adopted sister, I call her. We lived in the same apartment building. And I’ll never forget the way we first met. She was out walking her dog. I was walking a few yards in front of them. At one point she called out, ‘Tina—stop.’ And I turned around and said, ‘My name is Zina, not Tina.’ And Jackie laughed and said, ‘Ho, that’s funny. I was calling my dog. Her name’s Tina.’ And then we both laughed. And a little while later we were fast friends already and both in Jackie’s mother’s kitchen, a place where I was to spend much time. We were baking a cake. And when that cake was finished, well, I’m sure it’s the only cake in the history of baking that ever bounced. I mean, you could lift it a few inches above the plate, drop it and it would bounce.

“There was, of course, my Grandmother Bethune. She was always very special to me. As, still, she is. She lives in Buffalo, New York, and her home has always been a very dear place to me. As a girl, I would go there summers. I still go when I want to get away for a while, when I want to kind of run away.

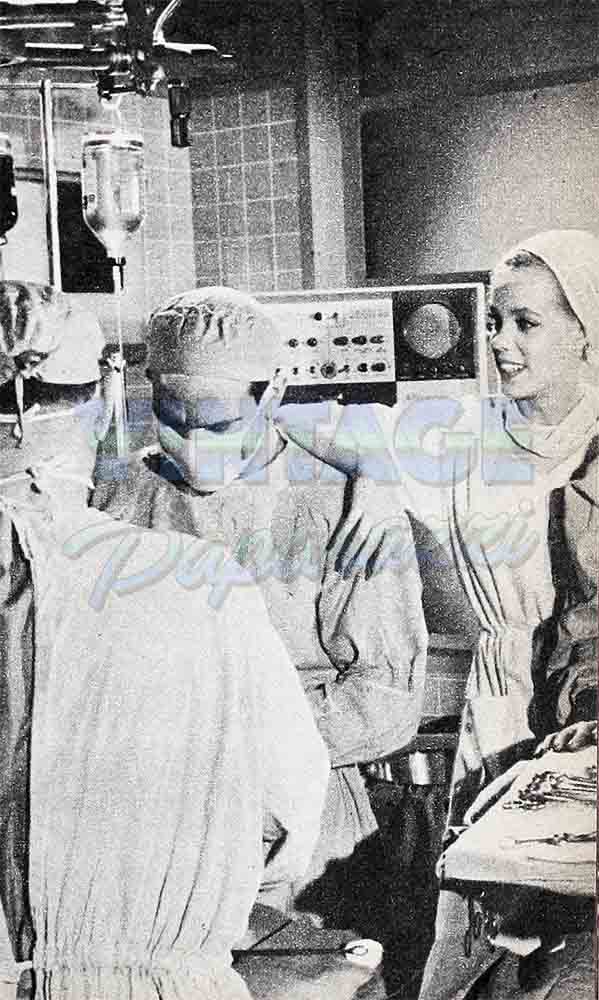

“Grandpa Bethune was a doctor. And Grandmother was a nurse before she married him. So she’s very proud, of course, that I now play a nurse. She watches the show faithfully. She even says she learns a lot from it, since nursing techniques have changed so much since her time.

“I can only get there rarely now. But my most treasured possessions are there, in that house. I’m a sentimental slob. Ever since I was a little girl I always saved every toy I ever received, until they bulged out of the big barrel I had for them. And one day not long ago my mother said to me, ‘Throw those things away, will you, Zina?’ And I said, ‘I can’t, I can’t.’ So, to compromise sort of, I shipped them up to Buffalo. And they’re in the attic there now—my toys.”

She remembered next the years that followed her childhood: “Dance recitals, lots of them . . . Ingenue with the New Dramatists . . . Robin in ‘The Guiding Light’ on CBS-TV, for three straight years . . . . Then Lisha, on ‘Young Dr. Malone,’ another year or so . . . In 1956, a Broadway musical: ‘The Most Happy Fella’. . . . Then a movie, playing young Anna Roosevelt in ‘Sunrise at Campobello.’ . . . Followed by more TV: ‘Route 66,’ ‘Cain’s Hundred,’ ‘Naked City,’ ‘The U.S. Steel Hour.’ . . . And the test for ‘The Nurses.’ ”

She remembered the day of the final test . . . “Shirl Conway had already been cast to play Liz Thorpe. Now they were down to three girls, testing them for looks—how they’d look next to Shirl. It was nervewracking in a way. But I managed to stay quite cool. The test was held down at Liederkranz Hall, where I’d done ‘Guiding Light.’ And I knew so many of the crew. And they were all so nice to me, like real friends. One of them even found it hard to recognize me, in my nurse’s outfit with my hair piled high under my cap, and he said to me, ‘My, my, Miss Bethune, but you’re really growing up.’

“When I got the part I realized that ‘The Nurses’ was going to be a serious show . . . That Gail Lucas, despite her sometimes youthful idealism, was going to be a serious role . . . And that I was growing up now . . . I was!”

She thought next of some of the pains of growing up, and of one particular pain which she had experienced recently . . . “I liked this young man so much. I thought he liked me. From the minute we met, well, he seemed to pay me so much attention. We went out quite a bit together. And, oh, the good times we had. I even used to think in the back of my mind that maybe someday he would ask me to marry him, and how wonderful that would be. I’ve always dreamed of being married and having a family. Not much different from millions of other girls, I know. But with me it was a very special dream. Because I thought that there was someone who thought I was very special. . . . But then, all of a sudden, it was over. My young man went off and got married to someone else. Just like that. I felt so bad about it—until I heard that the other girl had known him for six years. Then I thought how heartbreaking it would have been for her, after waiting, to have him run off and marry someone else. Like me. So I didn’t feel so bad.”

She continued staring down at the waiting birthday cake.

“Besides,” she thought, “I have so much work to keep me busy now—who can even think of men? I mean, five days a week —from seven in the morning till 7:30 at night, just on the set. Working. Working. Working so hard sometimes that you look over at an old wooden chair and it looks as comfortable as the biggest bed. . . . But—I love my work. I love this show. I love playing Gail Lucas. I find it very thrilling when people actually sit down to write to me. I find it thrilling when I’m recognized. And it’s even funny sometimes, too.

“Like the other night. When I went to the movies with my friend Lily Felcher. We’d gone to a theater in Lily’s neighborhood, to see ‘Barabbas.’ It must have been eleven o’clock when we got back to the new apartment where Lily, her mother and her sister live. We got into the elevator, and by some mistake we got off on the third floor instead of the fifth. I didn’t realize anything was wrong. And neither did Lily. She just walked over to the door which she thought was hers, got out her key, and began twisting it and twisting it into that lock. Until finally an old man opened the door. In his bathrobe. His eyes so bleary. And he looked at me as if to ask, ‘What the heck’s going on here?’ But his eyes suddenly popped open when he saw me. And he asked, instead. ‘Miss Lucas—what is it?’ And Lily and I didn’t know what to do. So we just turned around and began running up the stairs. And we giggled so much that our stomachs ached something awful—”

Zina smiled at the recollcetion.

“Hey,” a voice called out to her.

She looked up from the cake.

“Hey,” said the photographer, back alongside his camera now, “—enough’s enough. I didn’t mean for you to stand there posing all this time. I went and got that bulb fixed.”

“But I wasn’t posing,” Zina said.

“You’re still smiling,” said the photographer.

“I’m happy,” Zina said. “I was think- ing of something pretty funny.”

“Oh . . . well . . . good,” said the photographer. “Now then, back to work. Ready? Okay. . . . Deep breath, Zina and then when I say ‘three,” you blow out those candles.”

Zina nodded.

The photographer counted.

Zina blew on three.

The photographer got his picture at the same moment.

And suddenly it was all over . . . the little make-believe birthday party.

—DOUG BREWER

See Zina on CBS-TV’s “The Nurses’ on Thursday nights at 10-11 P.M. DST.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1963