The boy who makes you forget; George Chakiris

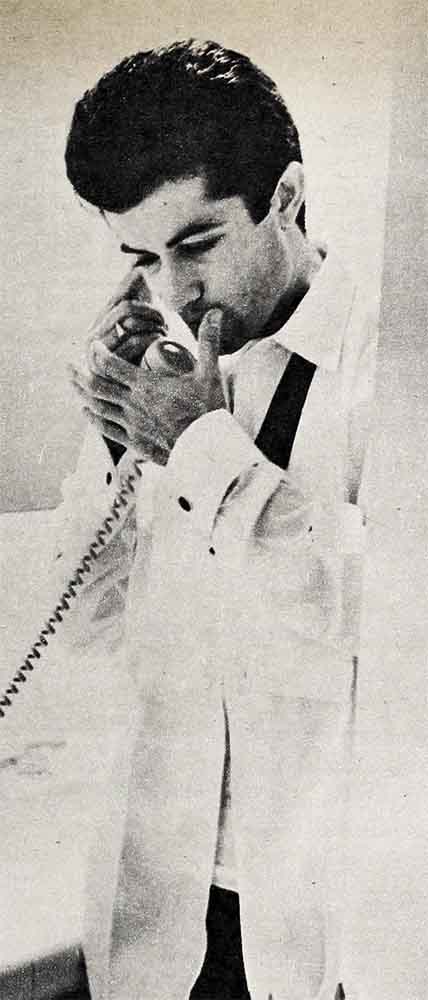

He sat there on the edge of the bed, a dark, handsome young man, short black hair tousled from sleep, blanket scrambled where he had thrown it when the phone rang suddenly in the first hours of a cold London dawn. The receiver lay in his hand, still alive with trans-oceanic static. The voice in New York had hung up, but the words crackled again in his mind: “George—You got it—yes—‘West Side Story’—yes—oh-did I say—they want you for Bernardo—congratulations. . . ”

When the voice was gone, he sat there.

Bernardo. But it was Riff he’d wanted. He knew Riff—he’d played him for six months here on the London stage. He was at home in the part. And now—Bernardo. His stomach turned over in disappointment.

“Why me?” he asked himself. He had tested for Riff, counted on it. He’d be nervous with the new role. Why did they have to pick him for Bernardo?

But he accepted, of course. Who in his right mind would say no to “West Side Story”?

Three weeks later, with dark makeup rubbed into his skin and his own brown eyes staring back from the mirror, he stood in a Hollywood dressing room wearing denims, a T-shirt, old sneakers.

Hesitantly, he picked up a thin, glittering knife and looked at it dumbly. Standing there with the face, clothes and weapon of Bernardo, he still wasn’t sure.

“It’s a tribute, George,” his agent had told him. “To your versatility. Look at it this way—in London you play Riff. He’s cocky, American, the big boss of the neighborhood. O.K. Now they want you to do the opposite. Bernardo—Puerto Rican—trying to get his foot in the door. Sure—a tribute . . .”

Riff—that was easy. After all, he was American. But Bernardo. . .

He stood remembering a dark night not long ago. He’d been visiting a friend who lived on New York’s West Side, near the river. It was after midnight when he walked down the four rickety flights of stairs, stuffed his hands in his pockets and headed down the dimly lit Street.

After a few minutes he became aware of the figures around him—dark shadows hunched on the dirty stone steps of rundown tenements. He saw their faces—boys his own age, pinched, lean, hostile, watching him with smoldering eyes.

He walked faster. Some wore jackets with emblems. They could have been the Puerto Rican “Sharks” or American “Jets” of “West Side Story.”

Except they were real. When they fought, they maimed and killed.

George clenched his fists inside his jacket, struggled to keep his steps measured. More boys hung around the corners, bound as if by an invisible cord of fear and hate.

He caught a glimpse of a girl’s pale, wistful face staring out of a dark first-floor window.

Somewhere, he thought, maybe in this very block, there are girls like Maria, who fail in love without thought of nationality, who pray for escape from the hell of gang wars, hate, prejudice, slums. . . . Somewhere, maybe sitting on those steps, are boys like Riff—born in America, fated to poverty, desperate to crush all rivals, anxious to make any mark on a harsh, unyielding life. . . . Somewhere, maybe an arm’s length away, was a boy like Bernardo. A boy who had come to America with hope, only to find hatred; who reached for happiness and found knives; who turned toward a dream and met death on dark streets.

Suddenly there was a warning sound, and he jumped! But he was in his own dressing room, and the buzzer was only his cue to come on the set. He slipped the knife inside his shirt, turned on quiet, sneakered feet and walked out.

On stage, the buzz of talk fell away. The klieg lights dimmed. He was standing on an empty Street. The dark slums loomed down on shadowy figures of Sharks and Jets ready to fight it out in the reflected glow of the distant Street lights.

George—Bernardo—stood slightly in front of his Sharks. A few yards away, Riff stood at the head of his Jets.

The tragedy that was about to happen was make-believe. But it was made out of reality. It had happened to flesh-and-blood boys on the city streets, and it would happen again. But now—before the cameras—it must happen to him!

His breathing became shallow, tense. He felt the pressure of the two gangs pushing toward each other—watchful—deadly. They edged closer, in ragged semi-circles around their leaders. In the split second that he hesitated, a thought came to nag at him: This isn’t my fight! It was a bad moment to be hit by such a thought—just when a boy must make it come real before the cameras.

George—Bernardo—stood with arched, taut body, the knife in his shirt. Riff inched nearer, pressed forward by the cluster of Jets.

George stared at the tight, pale faces. Not my fight, he thought again. But he knew, too, that he had to make it his fight. He had to feel the hot burn of hate for injustice and tyranny that was in Bernardo’s heart. He wore Bernardo’s clothes, his face, his knife—now he had to feel Bernardo’s slow rage in his heart. It had to be his fight!

His hand reached for the cold metal against his chest. The only sound now was the deadly rustle of boys’ feet. Then the knife flashed and the two half-circles of shadowy figures lunged.

Even as his hands touched the knife, he held back. He saw Riff’s face, pale in the wild black shadows . . . the frightened eyes held his for a last moment. Even then, something stopped him.

Not his fight? Or was it?

Then, as gang clashed against gang and threw him forward, something cried out in him—a mingling of rage and despair: I only wanted to be your friend! Why didn’t you let me?

His hand struck. A single, silent gleam in the night—and suddenly all the boys were gone. Except for two pitifully young figures crumpled on the cold pavement. Riff—and Bernardo.

There was a long moment of silence. Then, “That’s it! Cut!” Harsh floodlights turned the brooding slums into painted cardboard, the blood into greasepaint.

George picked himself up, collided with the director.

“Great, George!” Someone tapped his shoulder. “Terrific!” Someone else grabbed his hand. The stage filled up with actors, technicians, onlookers. Through the confusion he heard a girl’s high-pitched voice.

“. . . so good—George, you even made me forget you are Puerto Rican!”

He felt the rage rising in him like flame. Then he caught himself: Why? Why the anger? Why should a girl’s careless words cut so deep?

It seemed like a long time before he finally remembered . . . he wasn’t Puerto Rican at all. But he knew! He knew how it would have felt if he was. And he didn’t like it one bit—knowing how he would have felt at her thoughtless words.

So it was his fight after all!

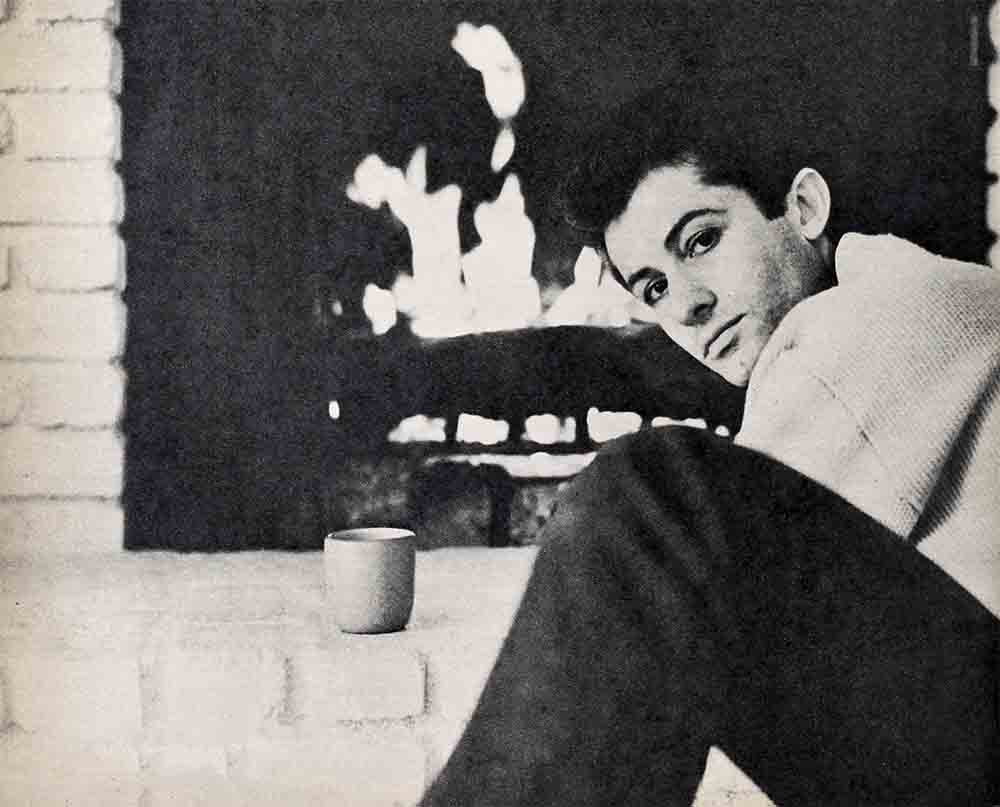

That night, George Chakiris walked away from the studio, shoved his hands into the pockets of an old sport jacket, dropped his eyes in a brooding stare and tried to think.

Passersby on Sunset Boulevard turned to take another look. He was handsome in a sensitive, off-beat way. Tall, with black, arched eyebrows, thick black hair, full, sensuous lower lip, dimple-cleft chin.

He never saw the stares, the half-smiles from women.

All he could think of was the rage and hurt that had welled up with explosive force inside him tonight. For one moment he had become Bernardo, lashing out at everything that had ever hurt him. . . .

He was back in his childhood, listening to his grandfather’s stories. With tears welling up in his eyes at the pitiful memories, the old man would describe how their people—Greeks living on Turkish soil—had to flee from massacre and butchery. The boy, big-eyed, lips parted, would hear how his own father and uncles and aunt, children then, ran for their lives to the ships that would take them to freedom—if they could board them in time! For all around them, in the sea, floated the murdered bodies of their friends who hadn’t made it!

They were old stories, handed down from father to son. But every time the boy heard them, he felt again a searing, scalding hatred for the kind of injustice and tyranny that makes one nation of people behave with cruelty to another.

In Turkey, his grandfather had been a proud, wealthy man. In America, in Ohio, he fed his family by running a candy store. He opened a beer garden and his sons worked for him. But when George was three, his father and mother, Steven and Zoe Chakiris, took him and his two brothers and four sisters away from Ohio to Tucson, Arizona. Later, when George was in public school, they picked up again, this time to Miami, Florida. And still later, to Long Beach, California.

Wherever they moved, Steven tried to work for himself, not for others, but he’d wind up in somebody’s Greek restaurant or driving a laundry truck.

And it wasn’t easy for a small, shy boy to move from school to school, to wear his brothers’ hand-me-downs and feel rootless when other children seemed so happy and secure. Many a time he stood at the edge of the playground longing to be part of “them”—yet hating the idea of belonging if it was going to cost him his independence. A young “loner” who nevertheless wanted friends. . . .

But how often, alone and watching, he had to writhe with anger and the shame of helplessness when the class bully picked on some classmate. How many times he said, “I hate to see anyone made fun of.” By instinct, he sided with the underdog. Yet he longed not to be one.

By the time George started high school in Long Beach he had a credo: “To be successful is to be accepted.” He was proud, like his father and grandfather. He vowed to achieve success. But he wasn’t sure how.

Perhaps as a singer? He had sung with a boys’ choir in Tucson, and the director had been enthusiastic.

Perhaps as a dancer? He sat enthralled through all the old Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers movies. He started to dance in high school, fell in love with the girl who danced best with him, followed her to college only to drift apart after a year.

Impetuous and intense, he dreamed of glory but lacked a sense of direction. “Just like a kid,” he says now, “I saw myself doing everything in show business, but nothing in particular.” He quit college, enrolled at the American School of Dance in Hollywood. He studied at night, worked as a clerk by day.

Now, when he remembers, it seems like a dream. He recalls the “tiny apartment—threadbare rug on the floor—no pictures—a chest of drawers and a bed—faded old denims—hamburgers—handouts from friends.”

With no money for dates, he hung around a gang of star-struck kids like himself: the outs—broke, always hungry, dreaming of the wonderful day when doors would open and Hollywood would take them to its great brass heart.

“It was my lowest financial and emotional point,” he recalls. “I was a failure, I had to hint for money from my parents. There’s nothing more discouraging.”

True, he danced in the chorus of four or five musicals. once, his hopes shot sky-high when queries poured in after his picture was in a magazine from a scene in “White Christmas.” Paramount looked him over, signed him up, then quickly forgot him. In June, 1958, he was still grabbing hamburgers, still ravenous with disappointment.

But by one of Hollywood’s ironies, two months later he had to take pep pills to get through a twenty-hour day. He had landed a job assisting a night-club choreographer; he did a TV spec, “Salute to Cole Porter,” and appeared in repeat portions of the show at the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas.

“I’d get up at 5 A.M., grab a bite and work till 2 A.M. the next morning,” he says. “I looked like a refugee—skinny, no time to shave.”

Seven weeks later the job ended and money got scarce again. In September, 1958, he spent his last dollar on a one-way ticket to New York.

A week after arriving, he took a tip from a friend and went to audition for the London cast of “West Side Story,” Broadway’s hit musical drama based on Arthur Laurents’ book about New York’s teen gang wars and the Puerto Rican problem. By October he was in London, sharing the play’s great success in the part of Riff. Six months later he was back in America at UA’s call for the film version. And asking himself, “Why me for Bernardo?” even after the shooting started and everyone kept assuring him he was perfect for the part, as if born to it.

“I thought a lot about Bernardo,” he explains now. “Who was he, anyway? A lonely kid who comes to America with all these phony ideas based on pictures and advertisements in magazines. He comes here hoping for the best, and ends up in a slum. He wants to belong, but finds that even the slums want no part of him. The American kids make fun of his clothes, the way he talks, the color of his skin.

“Bernardo is proud and Spanish. He rebels. He thinks—‘O.K. If you won’t let me be one of you, I’ll fight back.’ He only wants to belong, just like anybody else. He ends up killing and being killed.”

“Just like anybody else. . . .”

Who was he trying to kid? He meant, “Just like me. . . What he really meant was, “Just like the Bernardo in me.”

He knew what it was like to be of the under-dog race—in his bones he knew it, because it had happened to his father and his father’s father and all their kin. Wasn’t it only by the Grace of God they hadn’t all been slaughtered for being Greeks instead of Turks? . . . And for himself, didn’t he remember what it was to be a loner on alien “turf”—the new kid in town, the outsider—watching from a corner of the playground and aching to belong . . . or the sense of danger at school because he came from a family that spoke a foreign language at home and worshipped in a Greek Orthodox church like few other people in the United States?

“Yes,” says George now, “I finally got to recognize the Bernardo in me—but it was the studio that saw it way before I did. I was instinctively putting myself in Bernardo’s place when I got before the cameras—feeling his hurt at rejection and his need to fight back. Only I didn’t know why. Or maybe I didn’t remember. Or want to remember. I knew I was an American and that was good enough for me. But if you’ve got some Bernardo in you—it’s got to show up!”

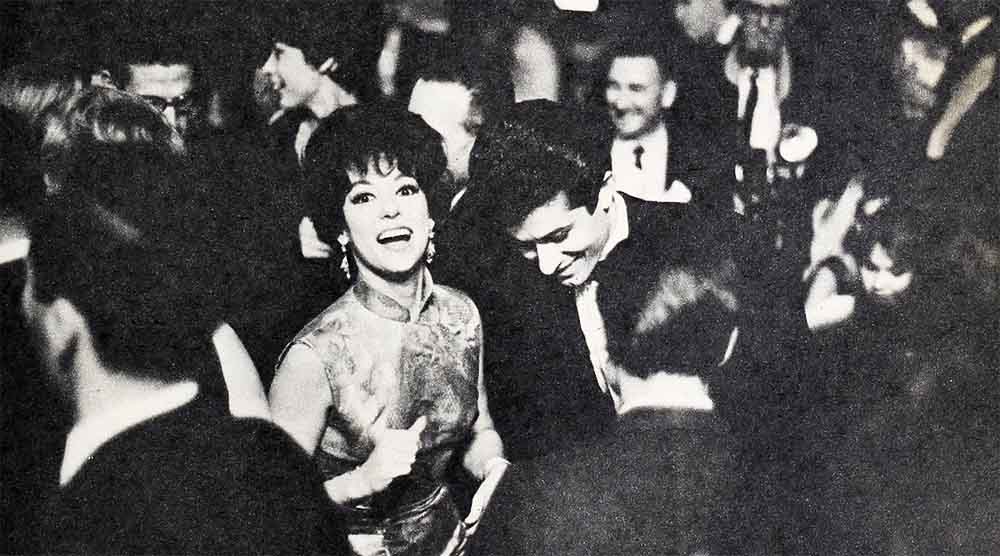

Today, George’s old high school credo has come true. “To be successful is to be accepted.” Successful and accepted, he is outwardly an easy-going young man who is often compared to Eddie Fisher in appearance. He spends money too easily, perhaps to make up for the years of deprivation. He talks smoothly, but keeps his real thoughts to himself.

So far, his dates are casual. He prefers to move on the fringe of Hollywood society, avoiding the big parties and publicity gimmicks. He lives with his parents, a younger brother and sister, but has “complete freedom” to come and go.

At twenty-eight he is outwardly sophisticated. Inwardly, he is stunned by his success. The years of dancing in a Hollywood chorus (“that’s as low as you can get”) were recent enough for him to remember the way people said, “Hey you over there!” even when they knew his name. Or snubbed him on the Street the day after he failed an audition.

He still wants to “belong.”

But he refuses to join Hollywood just for the sake of belonging.

“It’s all right,” he says, “to belong to something big. A club or society or fraternity. The danger is when the people who belong get the idea they’re superior—don’t ask me why—to those who don’t.

He fears there will always be Riffs and Bernardos and sad little Marias in the world. But he hopes he’s wrong—that some day even teen gangs may learn to live and let live. Then every boy can grow up strong, finish school, marry the girl he loves, raise a family and be happy.

He says these are the things we should know so we can live together in peace:

One side can never stop a fight alone. It has to come from both.

If someone tries to hit back, it’s usually because he was hurt—maybe for the color of his skin, or the way he speaks or the poverty and ignorance into which he was born.

Maybe he’s tried to get along, but no one gave him the chance.

“Maybe if kids learned to give each other that break,” George says, “it wouldn’t matter any more that one is Puerto Rican and one native-born American. or of Greek extraction or maybe Polish or Italian. If they could just learn to forget their prejudices—or rather the prejudices foisted on them by adults— then boys like Bernardo and Riff could meet on a football field instead of a dark alley.”

—JANE STANFORD

George is in “West Side Story” for UA and will be in “Diamond Head” for Col.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1962