The Woman And The Legend

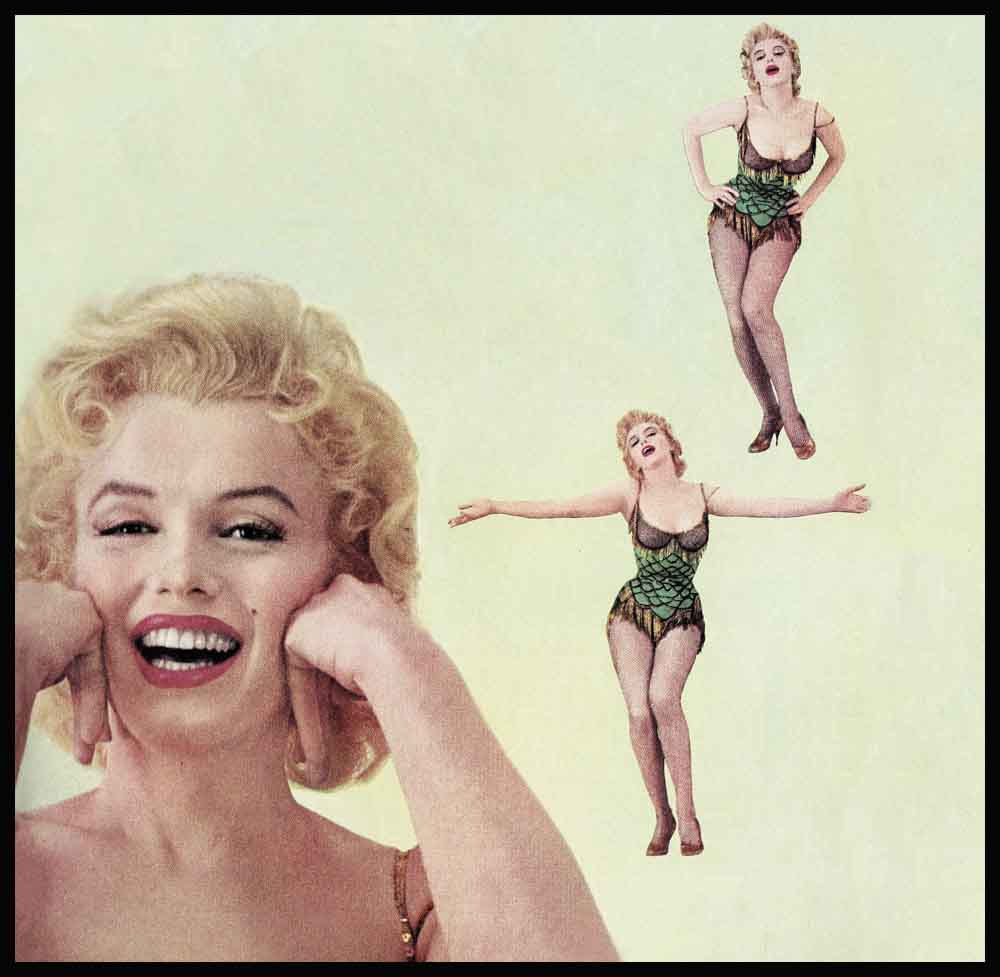

Once upon a time there were two women. Both of them were very beautiful, and both of them wanted, more than anything in the world, to be loved. One of these women took a childlike delight in the fact that she had a beautiful face and body. She was to become famous for such remarks as, “What do I sleep in? Why. Chanel No. 5,” and “I never suntan because love feeling blond all over.”

The other woman, equally beautiful, was more or less fascinated by the dizzying climb to success of the first woman who, in two brief years, became the symbol of sex to millions of her admirers, and an almost equal number of her detractors. This young woman was shy, hesitant. reserved—and terribly lonely.

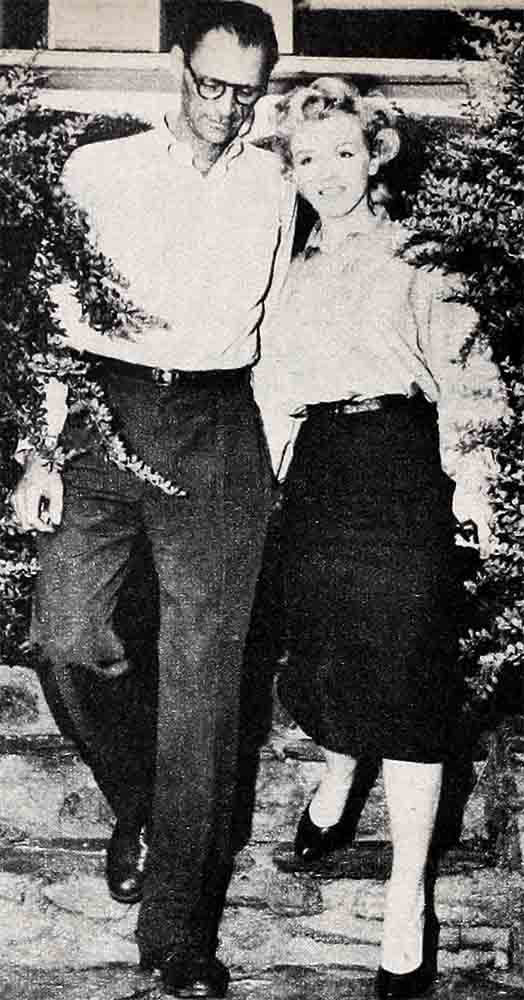

Both of these women were named, first, Norma Jean Baker, which later became Marilyn Monroe. And the latest thing this “two-in-one” woman did to become just a simple, uncomplicated person, seeking above all else, to love and be loved, was to change her name once more, this time to Marilyn Monroe Miller, wife of the famous playwright, Arthur Miller. Before then, she had made other bold steps toward blending these two personalities into one, once by marrying Joe DiMaggio and another time by breaking with her studio and leaving Hollywood.

Thus was born the story of Marilyn Monroe. It has become the story of a woman vs. a legend, with an equal number of admirers in each camp. There are those who know her hardly at all, who think that the legend—with its fame, its wealth, its admirers and its mink coats—would be rather foolish to try to settle for being a woman. And there are others who know the woman well, who hope with all their hearts that this time—when she has just been granted, so to speak, her third reprieve, her third chance at happiness—the woman will realize that her greatest enemy and the greatest threat to her happiness is this Frankenstein-like legend which has overshadowed and almost obscured the woman.

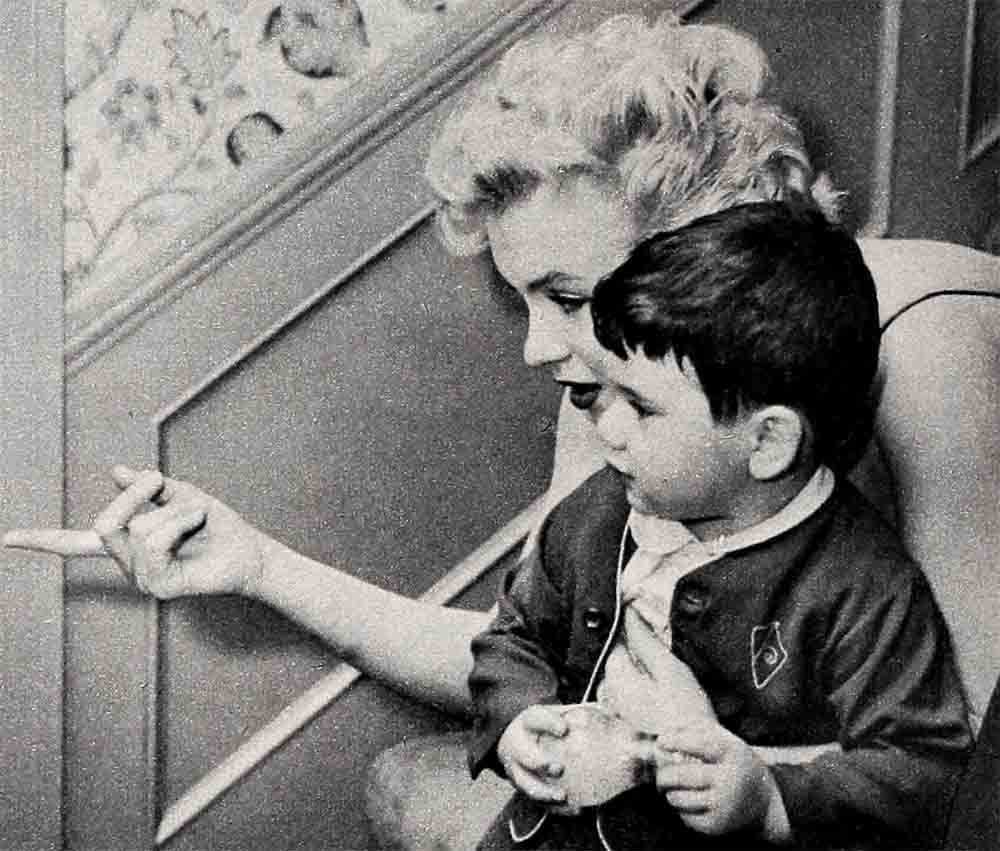

The final step on this road to becoming known as a woman and an actress first and a symbol of sex last and least will be, of course, when the woman also becomes a mother—because Marilyn has often expressed to friends her wish to have children. And anyone wondering or doubting how sincere is this wish, or speculating as to how good a mother Marilyn will make, would have been interested in a little incident that took place in Phoenix, Arizona, during the making of “Bus Stop.”

Seldom has a star worked under greater stress and strain. For instance, when “mob scenes” were called for, the mobs (mostly local people, hired on the spot) mobbed Marilyn, their cameras poised, instead of mobbing the rodeo stadium as they were meant-to do. With hoarse voice and short temper, Director Joshua Logan had to remind these good people that they were to do the job for which they were hired, while the Assistant Director, Milton Greene, who is Marilyn’s good friend and vice-president of Marilyn Monroe Productions, went about the job of separating the star from her enthusiastic admirers.

To complicate things further, Marilyn was suffering from the nervousness and exhaustion which attack her whenever she’s making a picture. Whenever possible, she would slip away for a rest from the noise, the confusion, the desert heat that beat down unmercifully and was so intense that make-up began to “blister” minutes after it had been applied and had to be removed by make-up men and applied all over again.

It was during one of these brief respites that the small incident occurred which reminded the few people who witnessed it that Marilyn Monroe, the woman, is as real as the much-publicized vision of Marilyn, the legend.

She was seated in a canvas-back chair in the bit of shade she had found outside one of the tents that were used for resting, make-up and hair repair, and so on. Her legs were stretched out in front of her, her shoes wearily kicked off. Eves closed, she held her aching head in one hand.

Suddenly, beside her, a small voice asked timidly, “You are Miss Monroe, aren’t you?”

The tousled and tired blond head came up and the famous slow Monroe smile went on. “Hello,” Marilyn said easily. “Yes, I’m Miss Monroe. And what’s your name?”

The little girl shyly advanced another step. “My father’s a photographer,” she said. “He’s here to take pictures of you. But I thought I’d like to come and talk to you.” And then, anxiously, “You don’t mind, do you?”

Marilyn reached out her hand and drew the child closer. “Of course I don’t mind. But,” she added, “shouldn’t a little girl your age be in school—or don’t you like school?”

“Oh, sure, I like it fine—only today’s a—well, today’s a sort of holiday.”

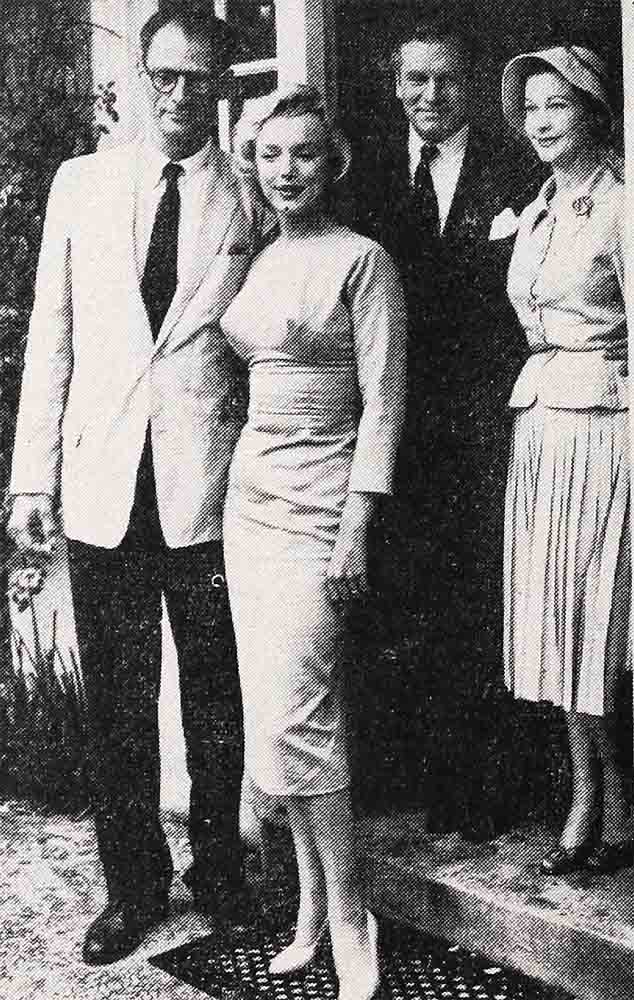

Visiting farm when pictures were taken was June Cunningham, English star who looks like Monroe

“I know what you mean,” Marilyn chuckled. “When I was your age and I had a chance to go to a movie or watch one being made, it was always a ‘holiday’ for me, too. But you mustn’t take too many of them, you know.”

Then the assistant director blew his whistle and all the many people who are in constant and personal attendance upon the star came dashing over to help her get ready for the next take. And standing there, watching her go, the little girl said breathlessly, “Gosh, she’s—why she’s just great!”

That’s Marilyn Monroe, the woman. That’s the woman who looks dreamily off into the distance and says, “Children, especially little girls, should always be told that they’re pretty and that people love them. If I have a little girl, I’ll always tell her how pretty she is, and I’ll brush her hair until it shines, and I’ll never let her alone for a minute.”

That’s the part of Marilyn Monroe that is still a shy, lonely little girl herself, and still unable to believe, completely, in the legend into which her beauty has transformed her and from which she has tried, from time to time, to run away.

One of these disappearing acts occurred just about two years ago, when she fled to New York. Her plane ticket, made out to Zelda Zonk, signified she hadn’t lost her sense of humor. Disguised in black wig, dark glasses and rumpled polo coat, tired and ill, she was unrecognized.

Marilyn’s bathroom leading fro the master bedroom. House has nine bedrooms, four bathroom

But it wasn’t long before Marilyn Monroe was identified. She announced herself a free agent—under contract to no one. She communed with nature in Connecticut part of the time, studied acting, moved about like a nomad from apartments to hotels and haunted the public library in Manhattan. The rest of the time, she caused a sensation at cocktail parties and charity premieres. Meanwhile, her fan mail dropped from a high of 10,000 letters a month to less than a thousand.

Twentieth Century-Fox left Marilyn’s deserted dressing room with the framed photo of Joe DiMaggio, the jumble of make-up, false eyelashes, medicine bottles, boxes of pills, the faint odor of Chanel No. 5, just as it was—a light in the window for the prodigal’s return. The fatted calf was a fat role in the movie version of the Broadway comedy hit, “Bus Stop,” and an amazing seven-year contract.

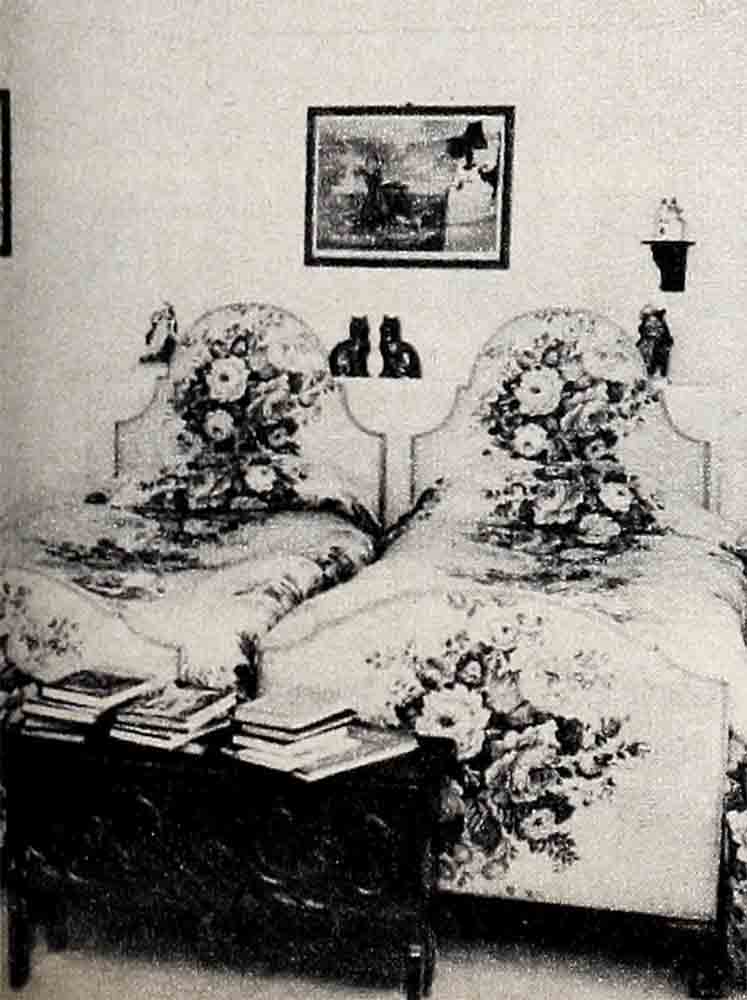

One of the guestrooms. All have breathtaking view of velvety lawns, gardens aglow with English flowers

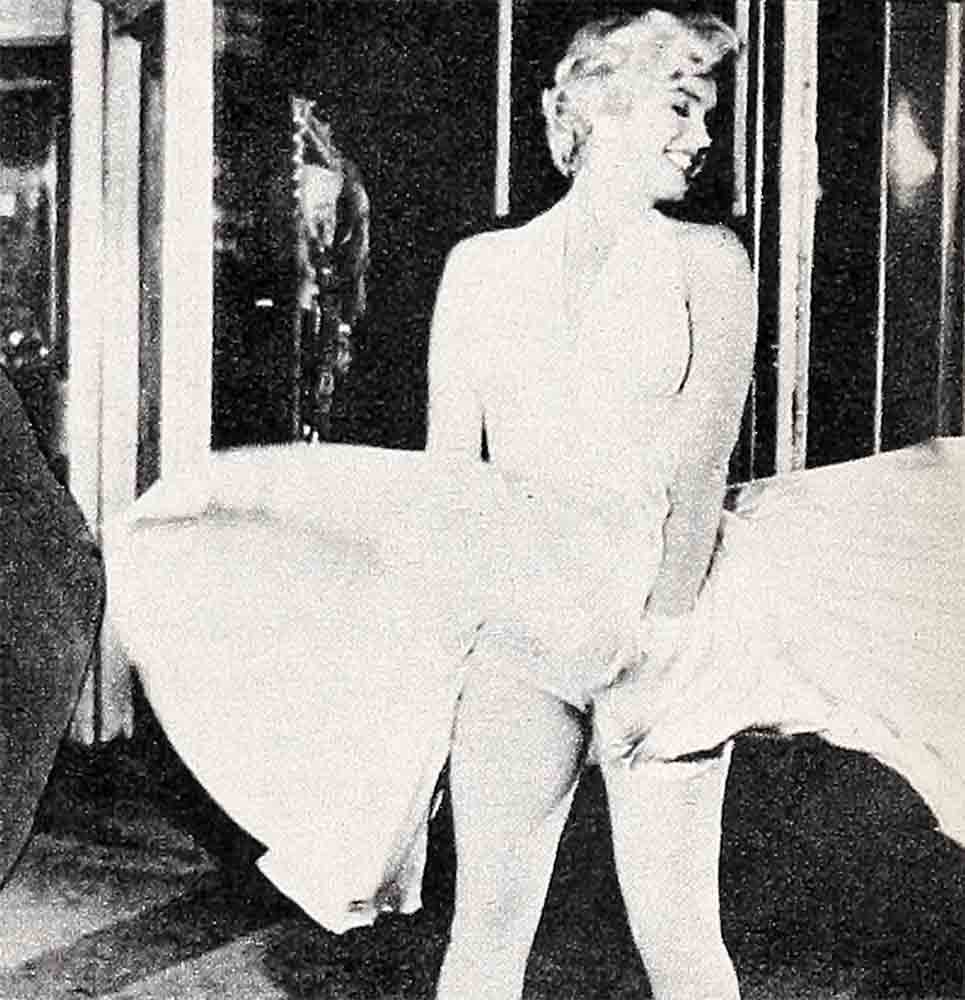

The prodigal returned from her New York sit-down strike, victorious as a conquering hero. True, as of bygone days, she kept a horde of impatient photographers and reporters waiting for an hour after the plane landed while she remained aboard to do a face and hair job. Her year-long sabbatical away from Hollywood may have taught her many things but she hadn’t forgotten her traffic-stopping horizontal walk down the plane’s ramp nor her sure ability to strike a pose while the photographers asked her to hold still for just “one more.”

One movie veteran chuckled, “What a gal! Marilyn’s new $400,000 contract for four pictures in seven years is one of the greatest single triumphs ever won by an actress against a powerfully entrenched major studio. No one believed she’d get away with it, but she won virtually everything she demanded. And, remember this, the money is paid to Marilyn Monroe Productions and so she’ll get to keep far more than a salaried actress. Marilyn Monroe may turn out to be not only the sexiest but the smartest blond of our time.”

She also became the most secretive. Trying to arrange interviews was harder than penetrating the Iron Curtain. Interest in the “New” Marilyn was tremendous. While she was in New York, a studio executive had remarked, “If she keeps herself on ice another six months she might as well not return, for the public is fickle and she’ll be forgotten. An entertainer, as is true of advertised products, must be kept before the public if they wish to retain its interest.” Marilyn, defying that basic advertising principle, emerged from her self-imposed retirement a more important personality than ever before.

She moved into a large, handsomely decorated Early-American house complete with swimming pool on Beverly Glen Boulevard, not far from the glittering Beverly Hills Hotel. The house was rented by Milton Greene and his wife, Amy, for the duration of “Bus Stop.” In addition to their two-year-old son, Joshua, the Greenes brought their household couple.

“Some people wondered why Marilyn had moved in with the Greenes,” a confidant of Marilyn’s explained. “But Marilyn loves to be part of a warm family circle. She’s lazy, and dislikes doing things for herself, and with her work schedule she hasn’t time for the responsibilities of running a home. And, most of all, she hates the loneliness of living in hotels which she did for so much of the time. Her apartments always had a sparsely furnished air about them as though she’d just moved in—even months later. She talked of changes she planned to make but never got around to them. Nor did she ever hang up her clothes or remove the piles of books and records lying on the floor. Once she shared a Hollywood apartment with her dramatic coach, Natasha Lytess and Natasha’s little daughter, Barbara, for almost a year. Marilyn and the child became great pals. The same thing happened with the Greenes’ little boy, Josh. Marilyn gets on extraordinarily well with children. Some cruel cynic has called it a meeting of minds, but that’s far from true.”

In what ways does the “New” Marilyn differ from the old? Has she improved as an actress? What did her holdout do for her? Under whose influence was she now operating? For with Marilyn there’s always a guiding hand—at the most a Svengali-like influence; at the least, a freer, pseudo father-daughter relationship. This dependency, and her need for protection will probably lessen now that she is married to a man whom she can look up to on every level of life and learning. Marilyn has always worried a decision like a dog worries a bone; she dreads making decisions because she can’t be sure she’s right. Thus, in many cases, the last person who has her ear, has her confidence as well. She hates responsibility, loves having others take care of the parking fines she’s forgotten about, pay bills she’s neglected to pay, get her packed and ready to travel.

Formerly, for varying periods, her guiding hand was the late actors’ agent Johnny Hyde, then film executive Joseph Schenk, dramatic coaches Natasha Lytess and the late Michael Chekhov, Joe DiMaggio, columnist Sidney Skolsky, music coach Hal Schaefer, actors’ agents Hugh French and Charles Feldman, New York lawyer Frank Delaney. Today a new cast has taken over—Milton Greene and his wife Amy; dramatic coach Paula Strasberg and her husband Lee Strasberg, head of the New York Actors’ Studio; Broadway director Josh Logan; agent Lew Wasserman; lawyer Irving Stein, and even before their marriage, playwright Arthur Miller.

In order to show off the “New” Marilyn to the press, the studio staged a cocktail party at Marilyn’s home. The invitations said five o’clock. Milton Greene and his tiny, beautifully dressed wife circled around but Marilyn didn’t make her grand entrance into the living room until an hour and a half later—proving, at least, that time-wise, she hadn’t changed at all. She immediately disarmed the skeptical reporters by greeting them warmly, remembering their names and recalling the last time she’d spoken with them. Her black satin Empire-line sheath dress was held up with tiny straps, her hair was tousled and shorter than last year, and single-strand cultured pearl earrings almost reached her shoulders.

It was obvious that the months in New York had wrought an incredible change in her personality. Gone was the shy, tense, little-girl voice, the slow groping for just the right word, the hesitation in answering a question, the throaty, Russian diction of her former coach, Natasha Lytess. In its place was a poised woman who could take command of a party. Gay, relaxed, less self-conscious, she came up in a few minutes with sprightlier conversation than most stars can manage in hours. But she hadn’t forgotten how to undulate in black satin, nor to keep her moist lips half open, her melting, blue, innocent eyes heavy-lidded.

One male reporter handing her a glass of sherry, protested, “Really, Marilyn, those shoulder straps falling all the time. It’s very distracting.” Marilyn turned the full candlepower of her heavily fringed eyes full on him. “I can’t help it,” she whispered, slipping the slender straps up again. “I’ve lost weight. They keep coming down. This dress swims on me.”

She had lost weight. She was far less hippy and flatter across the middle than formerly, although all the necessary curves remained. She explained that she rode a bike for an hour every morning before reporting to the studio, hoped to “stay this way, eating only meat, eggs and vegetables. I can have two glasses of sherry before dinner but no cocktails and I mustn’t touch any hors d’oeuvres.” She sadly shook her curls at the maid who presented a platter of them.

Josh Greene, a sturdy, black-haired image of his photographer-father, wandered in, called Marilyn “Auntie,” and smiled at her with evident affection. “I love being with them,” she said of the Greene family. “It’s the first home life I’ve had in a long time.”

Later, I sought out Marilyn in her dressing room for more intimate revelations of how she’d changed in her fourteen months away from Hollywood.

“Why does everyone ask,” she demanded, a little frown wrinkling her milk-white brow, “whether or not I’ve changed? They’ve been asking me that same question over and over again. I’m exactly the same person I’ve always been. What makes you think I’ve changed?”

“You’ve won a great victory over the studio,” I pointed out. “You’ve formed your own production company and studied at the most famous dramatic school in the country. You’ve associated with top theatrical personalities and literary intellectuals. And you’re getting one of the world’s top actors, Sir Laurence Olivier, to direct and star opposite you in ‘The Sleeping Prince.’ You’ve fought for what you believed in against great odds, and we’re proud of you.”

“Well,” she hesitated, “maybe you can say I’ve matured a little, psychologically. In a sense, everybody undergoes change all the time—or they’re dead. Some people have been unkind. If I say I want to grow as an actress, they look at my figure. If I say I want to develop, to learn my craft, they laugh. Somehow they don’t expect me to be serious about my work. I’m more serious about that than anything. But people persist in thinking that I’ve pretensions of turning into a Bernhardt or a Duse—that I want to play Lady Macbeth. And what they’ll say when I work with Sir Laurence, I don’t know.”

In the air was the feeling that Marilyn was again troubled, shrinking back into the shadows, anxious, still unsure of herself and a little afraid. Thoughtfully, pensively, she went on to say, “It’s been said that I received $100,000 a picture before the new contract went into effect. But that’s not so. The main consideration with me was never money—it was the right to approve directors, to do only those roles I could believe in, to make outside films and eventually, when I’m ready, to appear in Broadway plays. I just couldn’t continue as a near-parody of sex. There has always been a part of me that nobody really knows about.

“When I was modeling, a long time ago, I wanted more than anything in the world for my picture to be on the cover of the Ladies’ Home Journal. Instead, I was always on magazine covers with names like Whiz Bang and Peek. Those were the kind of movies I made, too. You see what I mean?”

Then she said, a note of weariness creeping into her voice, “I’m still not over a virus infection I caught a long time ago. I don’t know why I catch every virus, flu and cold germ that’s around. Doctors have tried all kinds of tests and shots and can’t find the answer.”

Marilyn appeared wan, tired and tense. She wasn’t the same girl who, a little earlier, had presided over a gay, press cocktail party. Now she was a strange, bewildering girl, one whose defenselessness caught at your heart. Was she being hounded again by the old fears, sparked by the need of another of those decisions she hates to make? Was she again seeing the ghost of the legend looming up out of the shadows of the future to menace her happiness?

It is rumored that Marilyn personally paid for her coaching instruction with Paula Strasberg, wife of Lee Strasberg, and mother of Susan Strasberg.

Mrs. Strasberg is a practical, hardheaded woman, a wit and an intellectual, with no illusions about anything. “Sometimes I wonder what I’m doing here,” she said, when I asked her opinion of Marilyn’s acting talents. “I have a son at home, a husband and my daughter, who needs me. Yet I can’t go back to New York and leave Marilyn when she says she needs me. If I didn’t believe that Marilyn had real talent, I wouldn’t be here. There’s nothing sadder in the world than people with big ambitions and little talent. She has extraordinary range—nothing she does seems beyond her. She can give a great deal, if she’s allowed to.”

On the set of “Bus Stop,” there appeared to be a mutual admiration society between Marilyn and director Josh Logan, one of the giants of the modern theatre.

“Before I met Marilyn,” Logan explained, “I was impressed with the Monroe legend, the personality. Now Im more impressed by the person than the legend. She’s very exciting to work with. She grows as you watch her—not just playing a part, but actually living it.”

Now, Marilyn is in England, combining a honeymoon with Arthur Miller with making “The Sleeping Prince,” co-starring Sir Laurence Olivier. Now, too, the questions are beginning to be asked, questions that only Marilyn can answer: How long will this marriage to an intellectual such as Arthur Miller last? Will Marilyn again find herself posing for publicity pictures that reveal her as that legendary symbol of sex—the kind of publicity against which Jo DiMaggio rebelled, and against which, perhaps, Arthur Miller will also rebel? And, if she has to make a final choice—a clear-cut decision to be through forever with the legend—will she finally have enough confidence in herself as an actress and in Arthur Miller as her husband to be able to turn her back on the kind of role and the kind of poses which first made her famous?

Going into the home stretch, the legend and the woman are still pretty much neck-and-neck. But the people who know her best, believe that Marilyn’s newfound confidence in herself as an actress and her new-found love, will probably combine to give her the courage to be herself—and just herself—at last.

And that, I might add, is something rather wonderful.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1956

No Comments