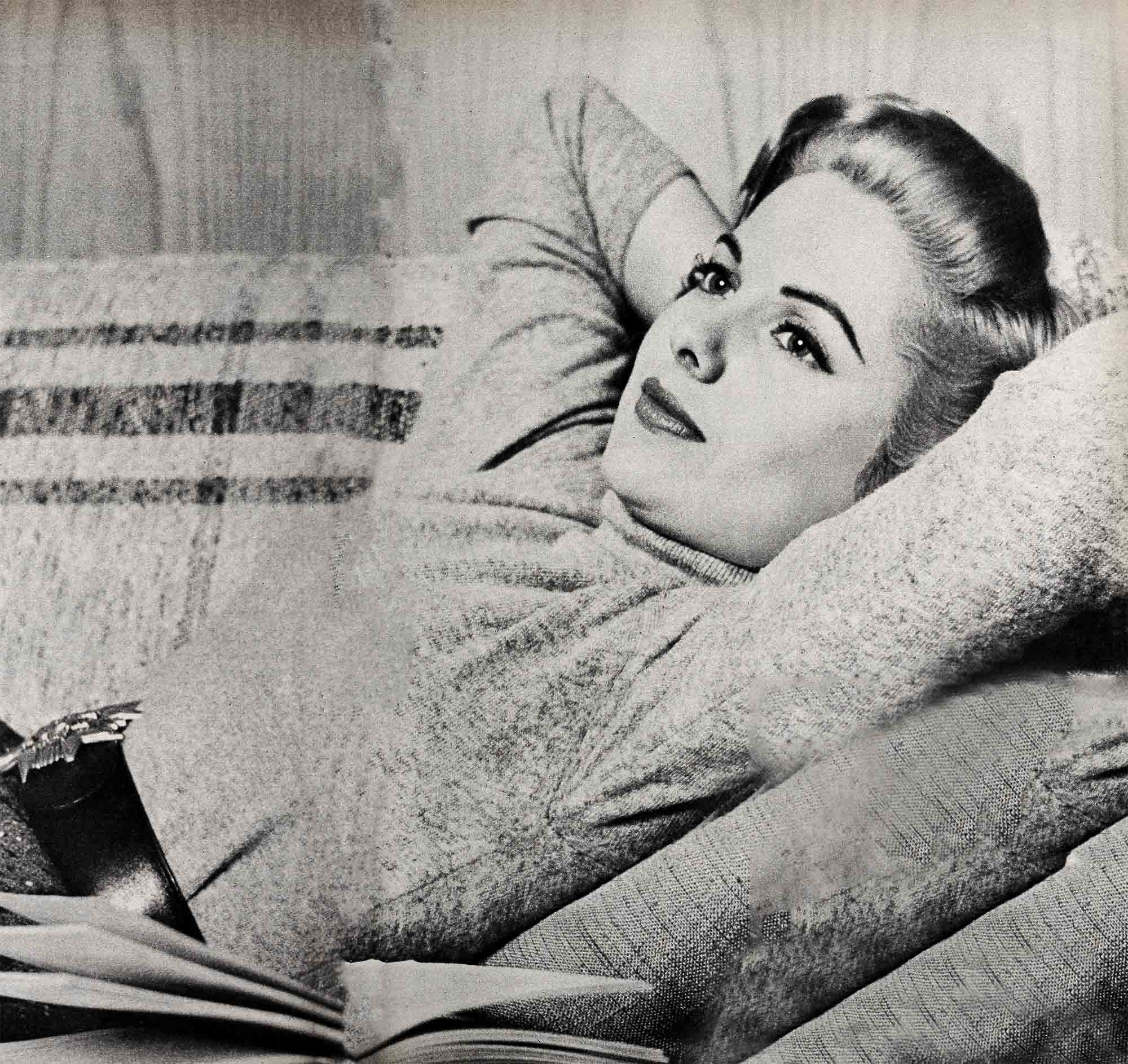

The Girl Who Refused To Get Lost—Martha Hyer

The taxi meter was ticking merrily, but the cab was standing quite still at the entrance to Universal-International Studios. The bewildered driver had turned off the motor, pushed back his cap and resigned himself to a long wait.

He had to admit that his passenger seemed like a girl who had all of her marbles. Pretty, too. Nevertheless, he couldn’t help wondering what she was trying to prove. When he’d asked if she was in movies, she’d said yes. However, the policeman at the studio gate was of a different opinion.

At the moment, the studio cop was on the telephone inside the gatehouse. “That’s right,” he was saying. “She says she’s Martha Hyer. It’s just that she doesn’t look like the Martha Hyer I’ve seen in pictures. And she has no identification.”

As he talked, the girl in the back seat of the cab restlessly tapped her foot. It was such an old story by now that she could hardly be indignant. Occasionally, the idea that she was a movie star made her laugh. Her name, she’d found, was always familiar—but her face remained unknown.

She couldn’t blame the skeptics. Her first big break had come with a picture called “So Big.” Her hair was a reddish brown at the time. For her next film, she’d had to lighten her locks to contrast with the coloring of the leading lady. In “Lucky Me,” which followed, Doris Day had held priority as the fair-haired lead and Martha had become a redhead.

Then came “Sabrina,” with brunette Audrey Hepburn. Someone had to dye. “You’ll be lovely as a blond,” they told Martha and, according to those who saw the movie, she was, indeed. But her family back in Texas found it necessary to point her out to some of the neighbors when “Sabrina” came their way.

After that, Martha had decided to remain a blond. Consequently, she was now en route to the hairdressing department to don the long black wig they’d given her for her first picture under her new U-I contract. That is, provided she could get into the studio.

She glanced out of the window and saw the studio cop returning. “Guess you’re Martha Hyer, all right,” he grinned. “At east the Casting Department seems fairly sure of it.”

“Someday,” Martha vowed as the cab rolled toward the soundstage, “someday, someone is going to recognize me!”

And someone did. In the 1955 Choose Your Stars contest, the readers of PHOTOPLAY voted her a runner-up. To Martha, it meant that the fans had finally recognized her as a person and as a personality, rather than a name with a face that could never be placed. It meant that movie- goers were interested in her and believed in her future. And it confirmed her own belief in that future. “The results carried a great deal of weight at the studio,” Martha says, happily. “Since the contest I’ve been given the kind of roles I’ve always hoped to play at U-I—a meaty part in ‘Kelly and Me,’ and another gem opposite Rock Hudson in ‘Battle Hymn.’ And they’re letting me look like me!”

Hollywood can tell you that Martha Hyer’s current success is also due to talent, perseverance, work, eternal optimism, and still another quality—courage. “Martha’s probably had as many setbacks as anyone in the business,” one of her friends said recently. “But she’s always taken them as lessons, absorbed them and put them to work for her later. She’s never been afraid to take stock of her life and make changes when they were necessary. And then, too, smiled the friend, range plan of hers.”

The setbacks, the taking-stock and the plan had their beginnings in Fort Worth, Texas, not so many years ago. First there was a near-tragedy. . . .

Martha has a vivid recollection of the rainy evening when the school dance ended at Arlington Heights High and the kids crowded into their cars to head for home. She and her date, in the back seat, struck up a song. Then suddenly the song was replaced by a screech of brakes, the skid of tires on wet pavement, screams, and a crash.

When Martha regained consciousness, there was pain in her right leg and she tasted blood on her lips. Her first thought was about her teeth. She’d just had the braces removed. After all that, what if something had happened to her teeth? She put a hand to her mouth and sighed with relief. The blood was from her lip which had been cut.

She tried to look around. The others—they were there. As far as she could tell they seemed all right, though badly shaken up. People were beginning to crowd around. They said the car had hit a telephone pole, that an ambulance was on the way. “What hospital shall we take you to?” someone asked her.

“Cook County,” was the first that came to her mind. It was the most beautiful in the city. Martha had always thought that if she were ever ill she’d like to go there. The pain grew sharp . . . someone lifted her into the ambulance.

At the hospital, Martha and her family learned that her right leg had been crushed and twisted. She would be hospitalized for several months and then she would go home—for a long time.

In school, Martha had been one of the most active girls in the junior class. She was a Cadet sponsor. She belonged to several clubs. Now, for the rest of the year, she would have to take her classes at home in bed. It wasn’t so bad at the start. Friends stopped by in droves. “But as the novelty wore off and the months went by I was terribly lonely,” she remembers. “It gave me a lot of time to think and to grow up a little. That’s when I began to plan my life and what I was going to do with it.”

Martha had never had much to say about her ambition to act. She hadn’t wanted to be teased. Yet the thought had been there since she was a child painstakingly constructing a stage from the long chest and the rolls of old wallpaper in the attic. And she’d always been the one to stage the productions—thereby assuring herself of leading roles.

The idea had grown more definite each Saturday. A Saturday afternoon meant hamburgers, malts and motion pictures to the three Hyer girls—Martha, Agnes Ann and Jean. Their father, an attorney, had done some legal work for one of the local theatre managers and the manager had given the entire family a permanent pass to the shows. It was fortunate because their allowances could go for other luxuries such as popcorn and candy. But, as far as Martha was concerned, the play was the thing.

Summer trips to California had left her quite certain of her ambition. The family had visited relatives in Pasadena and Whittier. They’d gone through several movie studios, and once they’d even gotten seats in the bleachers to watch the glamour of a Hollywood premiere. To Martha, nothing could have been more exciting.

Thus, as she lay in her bed, recovering from her accident, she needed a dream to old onto. She needed a goal, a plan. Martha Hyer was going to be a movie star if. And there was a king-sized if. She’d learned that, until the cast was removed from her leg, the doctor would not be able to tell whether she would ever walk again.

“The waiting was terrible,” says Martha today. “But it did a lot for me in a great many ways. It made me stop and say to myself, ‘If I can come out of it and be all right, I’ll try to remember how fortunate I am to have my health—no matter what happens. I can take anything.’ ”

When the cast came off, there was a celebration in the Hyer family. The doctor announced that Martha would walk—eventually. The following fall she went back to school on crutches.

Upon graduation, Martha took her first step toward Hollywood—although she went in the opposite direction, to Virginia. “My family was able to send all three of us to college,” she explains. “And Mother and Dad asked that we graduate. After that, our lives would be our own.”

Martha entered Fairfax Hall, a well-known Virginia finishing school for girls, for two years, then planned to take her degree at a large university. At Fairfax, she applied herself, won the school’s Honor Medal and was valedictorian of her graduating class.

Healthwise, swimming in the school’s heated pool had done wonders for her leg. At the end of her first year in Virginia, she’d still had a slight limp, so she’d gone to Johns Hopkins in Baltimore for a check-up. She was told that an operation could be performed, but the surgery was inadvisable. It would leave a bad scar and there was no assurance that the operation would be a success. So Martha had continued swimming in the pool and the leg had steadily improved. After two years at Fairfax Hall, the limp had all but disappeared. Today, no trace of it remains.

Upon graduation from Fairfax, Martha went on to Northwestern University, which boasts such alumni as Jeff Hunter, Peggy Dow, Charlton Heston and Lydia Clark. She entered as a junior, pledged Pi Beta Phi sorority, and will never forget her first days as a pledge. The chore assigned her was that of scrubbing a campus sidewalk with a toothbrush. “And I worked hard at it,” she grins. “I was a conformist.”

Martha was also a businesswoman. She found employment in a candy store, she modeled, she was a baby-sitter. She loved reading to the babies, although she often wondered if they appreciated the extent of her talent. Every so often one of them would begin to nod and go into a deep doze. “I still get letters from the mothers of the children I sat with,” she says. “They keep me posted on all of the small-fry activity in Chicago!”

And once again she buckled down to her studies, winning the speech department’s highest award. “Yet I did as so many other students do,” says Martha. “I memorized everything. Oh, I could pass tests with flying colors—but two days later someone would throw me a question and I’d go blank and mutter, ‘Don’t ask me!’

“I never really started learning until my senior year in college,” Martha continues. “It was only then that I realized the great and wonderful thing of understanding and thinking about what I was studying.”

As soon as final exams were over, Martha was on her way. She bought a one-way ticket to California out of the ample funds she’d saved. “Once I was out of school,” she explains, “I didn’t want to ask my family for financial help.” She’d even acquired a wardrobe for the trip, purchased with her own money. She was so anxious to register at the Pasadena Playhouse, that she didn’t wait for her diploma. It caught up with her later, via the mails, at the Playhouse dormitory.

The way Martha saw it, Hollywood could come to her. However, as she joined the other students for her first class, she began to have her doubts. The instructor had prepared a speech for the newcomers. “Many of you,” he began, “may be under the illusion that a Cadillac is going to drive up and whisk you away to a studio where you’ll become great stars, immediately if not sooner.” He paused for a moment, and the class waited breathlessly. “If that’s what you think,” he concluded, “forget it.”

There were classes in the mornings, rehearsals during the afternoons, performances at night. For her initial role, Martha drew a fine acting part—one that allowed her to wear what is known in the trade as a knockout of a wardrobe. “This is it,” she ae “I’ll be discovered in no time at all.”

However, no talent scout appeared during the run of the show. “Next time let’s make certain,” Martha suggested to some of the other girls in the class.

Together, they pored over every fan magazine in existence, and devoured the trade papers for names of agents and any kind of lead. “We mailed letters and tickets to every agent and talent scout in Hollywood,” Martha recalls. “We must have sent hundreds.”

As a result, she also remembers, “One showed up. Milt Lewis of Paramount.”

However, it was a start—even though nothing came of it other than a request that she come to the studio for a reading. Martha complied, then was told that the studio would get in touch with her at a later date. So she settled down to wait, and hope.

In the meantime, Martha’s father, who had gone into the Army during the war, had become Judge Advocate of the 15th Army. It happened that singer Ella Logan, doing USO work, stopped by Colonel Hyer’s office one afternoon. She saw a picture of Martha on the colonel’s desk. “My daughter,” he said. “She’s in California now and very much interested in the entertainment business.”

“Does she have an agent?” Miss Logan asked. “I don’t believe so,” replied Martha’s dad.

“I’d like to help her,” said the singer. “I’ll wire my agent to call her.”

When Miss Logan’s agent called, he learned that Martha had finished her training at the Pasadena Playhouse, and they arranged to meet. By this time, the Hyer cash and spirit had dropped pretty low; she’d still had no word from Paramount.

Martha stopped in at the agent’s office and had a long talk with him. “If you don’t hear from Paramount soon,” he told her, “call me. I know some people at RKO.”

So Martha waited some more. But, since even glamour girls must eat, she took a job selling pots and pans in a store basement. She also did away with the high cost of lunches. Ten cents would buy an apple and a candy bar, and that would be enough for a noonday meal, she concluded.

Unfortunately, Martha had chosen to invade Hollywood at a time when studio production had fallen off. Paramount had nibbled, but not bitten, at the bait. Although Martha read for the talent department several times, she finally received word that they were not making any screen tests. The best they could do was offer her a bit part in a Bob Hope picture. “Let’s try RKO,” the agent suggested one day. “Meet me there at 10 a.m. Tomorrow.”

The RKO studio head was a kindly man who did his best to put a nervous Martha at ease. “Tell me about yourself,” he said.

After telling him her life story, Martha paused. “Well,” said the studio head through the silence, “go on.”

Martha devoted a frantic moment to frantic thinking. What else was there to say? If the studio had no need for actresses, she meekly volunteered, she could paint scenery. The studio head smiled and asked her to wait in his outer office. The minutes dragged by until her agent reappeared. “Come in and meet your new boss,” he said.

When Martha realized she was being signed to an RKO contract, she said to herself, “This is really it. Once you get a contract, everything’s assured.”

She didn’t realize that a contract is only the beginning . . . that her first pictures would be photographs . . . that she was on her way to becoming the star of the still gallery. Nevertheless, Martha promptly became Miss Cooperation. It seemed she was forever posing—for St. Patrick’s Day art, Christmas art, Easter art, and Happy New Year art. “Call Martha,” became the byword when someone else couldn’t arrange to make it for a sitting.

Eventually she made movies. She appeared in ten Westerns. It was hardly what she’d expected, playing second fiddle to a horse and a collection of firearms, but she learned camera angles. She was seen on film—and, typically, she made the most of it. Then, when Howard Hughes took over RKO, her option was dropped.

“It was another bad period in the industry,” says Martha. “Production was off again and jobs were anything but plentiful. I did several films free-lance—one in Australia, with Jock Mahoney. And after that, I did a couple of other small ones. And then I got married.”

Of this period, Martha speaks very sparingly. She married young writer-director Ray Stahl, son of director John M. Stahl. They lived in Japan for almost a year and Martha made two pictures there. Next they moved to London for three months and then to Africa, where they lived for six months and worked on a British picture. Martha was completely captivated by Africa. “Someday I’m going back,” she vows. “The Kenya safari was something I’ll never forget.” All told, she was away from American picture-making for a good two years.

After two years of marriage, Martha and her husband decided to separate. “I made plans to return to the States,” is all she says in explanation, “to file suit for divorce and to resume my Hollywood career.”

Her agent had written that there was a perfect part for her in the Warner Brothers production of “So Big.” It was a departure from all her previous roles, when she’d played ingenues. “So Big” called for the “other woman” type of role. It was, in some ways, a drastic change. “But it was time for a change,” says Martha. “Id made one change when I went abroad, and I’ve never regretted it.”

She wasn’t quite prepared, however, for the many other changes in store for her. And she wasn’t very happy about having to change her appearance with every role—especially since the first step toward becoming a well-known personality is to become known, period.

“But the roles were there,” says Martha, “and they meant more experience.”

The decision paid off. A Universal-International executive noted her performance in “Sabrina” and suggested that Martha be placed under contract.

After she’d signed with U-I, Martha reestablished herself permanently in Hollywood. She rented an apartment in a Danish-style farmhouse and helped paint and decorate it. She also began to collect paintings. “I have several originals which I prize very highly,” she says. And since she dabbles in oils on her days off, she adds, “I also have several Early Hyers.”

Next, Martha bought her first car—a black Thunderbird—and promptly enrolled in a driving school. Nowadays, she wheels through Los Angeles traffic with the greatest of ease.

“As for my love life,” says Martha, anticipating the question, “at the moment I’m not romantically inclined. There’s a doctor in San Francisco whom I see from time to time. And, of course, I hope to marry again someday. But right now I’m more interested in my career than anything else.”

With the release of “Kelly and Me” and “Battle Hymn,” folks in-the-know are predicting that Martha Hyer will attain full-fledged stardom—as a definite, unmistakable personality and actress. “Of course,” Martha grins, recalling the past, “I won’t really know I’ve arrived until the time someone else is asked to dye her hair in order to contrast with mine.”

It seems quite likely to us that such a time is not too far off.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1956

No Comments