Horst Buchholz’s Childhood Adventure

“I didn’t mean to lose the money,” Horst Buchholz said, with a slight German accent dotting his perfect English. “I was only a child then, only seven years old. I meant no harm. It was only that my head was always in the clouds, always filled with dreams. But my father didn’t understand—how could he understand when a son lost money that he had worked so hard to make. Always, I was running, running, delivering shoes before school, after school, on Saturdays, even Sundays. ‘Look, Hotte,’ my father would say, ‘here are some coins, you’ll need them to make change when customers pay you for the shoes.’ Every time he would tell me to be careful of the money, and every time I would lose it. Every time. When I had to tell him that I lost it, he would yell and slap me. But gradually, he saw that it was useless to hit me. He realized that I did not steal the money to use for myself. He came to take me for what I was, a child whose mind was crowded with fantasies of a better way of life.”

AUDIO BOOK

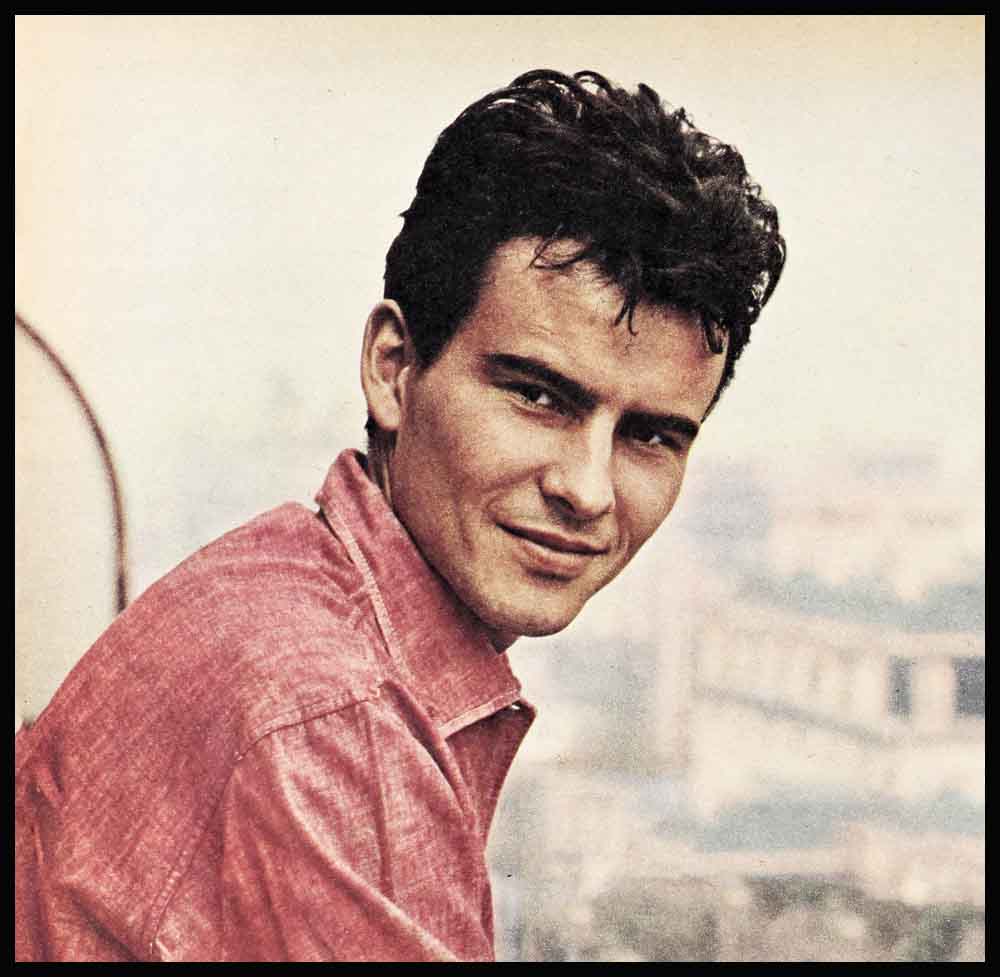

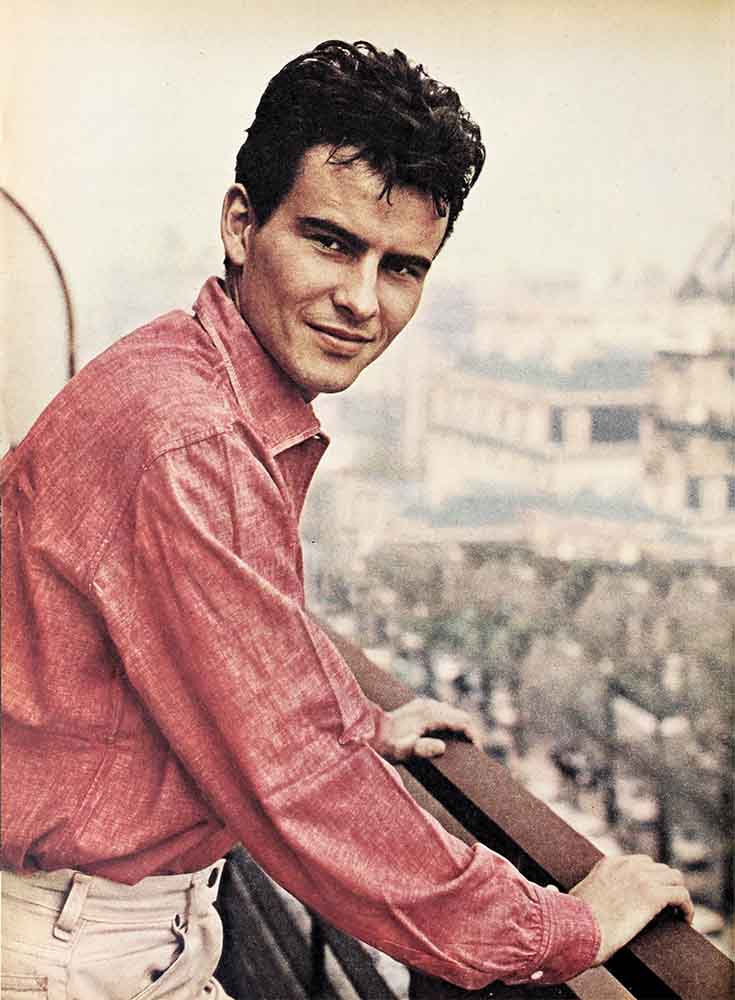

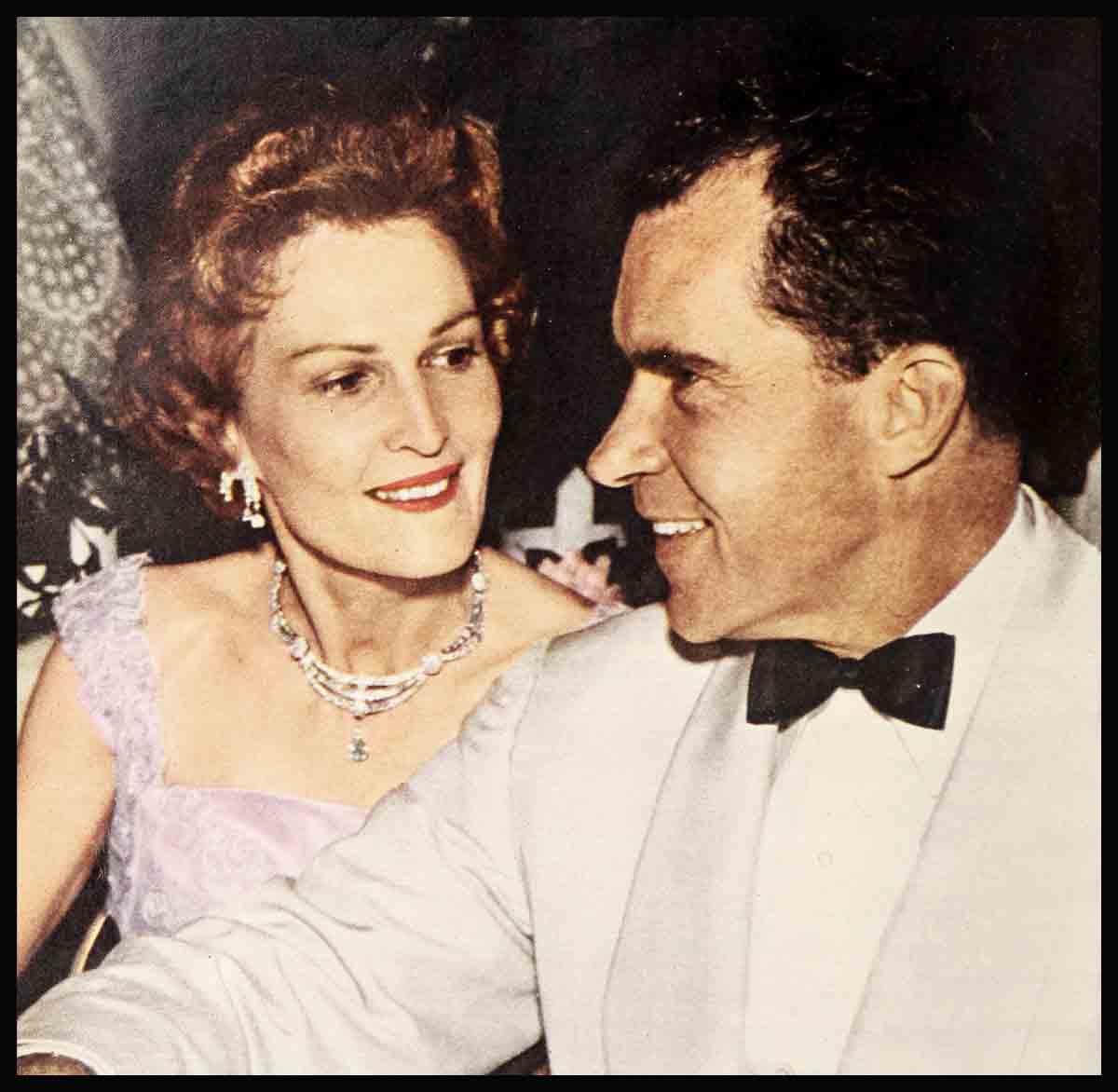

Now, more than twenty years later, Horst’s life is better, much better. As we lunched in Hollywood’s posh Scandia, the actor more than once looked around at the elegant surroundings, turned to his wife, Myriam, and said, “My childhood wasn’t like this—definitely, it wasn’t like this.”

And now, the same number of years later, his life is still filled with fantasies—but they are not of his own making. His parents had always hoped that he would study medicine, but war, bombings and prison camps stopped all that. In fact, before Horst was eight, his family was no longer together. His father was taken into the German Army, his mother and baby sister, Heidi, were sent away to stay with relatives in Frankfurt. Horst, along with some of his school chums, went to live a kind of prisoner’s life in a series of evacuation camps in Czechoslovakia. He tended cattle, hoed potatoes and he even learned to sew. And he was hungry, always hungry.

By 1945, Germany’s war machine was all but destroyed, and Germany itself was on the verge of collapse. War’s end, to Horst, meant only that now. perhaps, he would he able to find his mother, his father, his sister. The Russians were already overrunning the countryside, looting and pillaging. Horst and a couple of friends stole away one night from their camp, desperately determined to get back to Berlin.

It took them months. The boys slept in open frost-covered fields, under hayricks, in abandoned barns. They begged for food—or stole it, when they had to. once, riding in a dirty cattle car, the runaways survived a bombardment that destroyed the train and killed some of the other occupants. “And all the while,” Horst remembered, “we kept dodging those trigger-happy Russians.”

But still Horst and his pals ploddingly headed north to Berlin and home. They reached Magdeburg and the Elbe River—the dividing line between the American troops and the Russians. Only one bridge remained; the others had been bombed. No one could cross because the bridge was closed. There was only the river; a strong swimmer could make it.

“But it would have been insane to try,” Horst said. “One story had me actually swimming the Elbe; I did not. I was no hero; I wanted to live. There were machine gun emplacements there, and huge search- lights lighting up every inch of both river banks. We saw many corpses floating in the Elbe—people who had tried to get across,” Horst shuddered. “No, I had no wish to die.”

Luckily for Horst and his friends, a Red Cross worker found them and took them to another camp. There Horst stayed for almost a year, until he was free to move safely back to Berlin. “That camp really matured me,” said Horst. “By the time I was reunited with my mother and sister—my father stayed in a prisoner-of-war stockade until 1947—I was really a man.”

Now he was the sole support of his family. He went back to school, managed to find part-time work helping farmers in the fields, taking home a few potatoes, ears of corn or heads of cabbages that had been thrown away. Then one day, he heard that there might be work to be had at the Metropol Theater, where they needed children for walk-ons. Horst dashed down there, spoke to the manager. “Yes, we have a few openings,” the manager said. “We pay three marks a night.”

Three marks—seventy-five cents! To always-hungry Horst it was a fortune.

And because a thirteen-year-old lad was hungry, because he had to support his family, the Horst Buchholz of today was born. “There was no other reason,” Horst said, honestly. “I had no burning desire to become an actor. The theater meant nothing to me. I went into it only for the money, because I desperately needed work.”

Yet even at his young age Horst saw the wisdom of what his mother had always said to him: “A man must dare greatly to be happy.” He decided that if he were going to be an actor, he’d be as good as he knew how. He began taking acting lessons. He studied languages. “I wanted to be ready,” he said, “if my break ever came.” He got a small part in the Kestner play, “Emile and the Detectives.” over the next two years, movie producers came to him and asked him to dub their imported English films with German. He was a bit player in dozens of comic operas, appeared on Radio Berlin, often slept only three or four hours a night. He was all of fifteen.

There were stage plays and more movies—“Die Halbstarken,” “Heaven Without Stars”—films that made him the idol of Germany’s teenagers and brought him a much-coveted award at the Cannes Film Festival. Soon he was Germany’s leading young actor; at twenty, he was already a major Continental star. But the picture which was the first to gain him world-wide attention was Thomas Mann’s classic “The Confessions of Felix Krull.” In the world’s press, Horst, the boy who had to become a man at twelve, was acclaimed as “one of the great new actors of our times.”

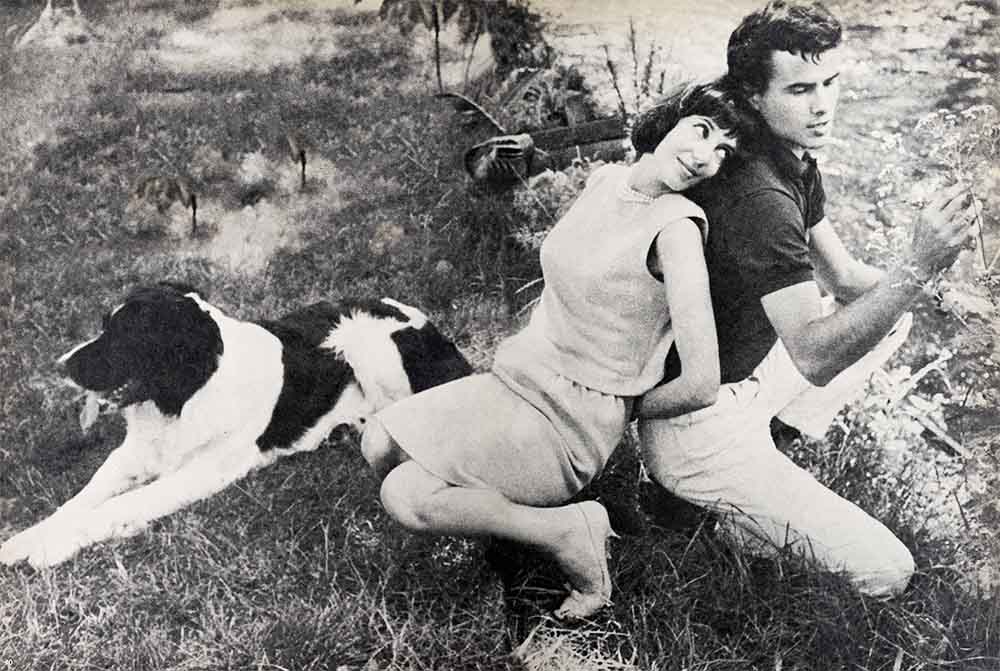

But to one girl, a lovely young French actress named Myriam Bru, the fame of Horst Buchholz didn’t mean a thing. Horst and Myriam first met in Munich, on the set of the Franco-Italian production of Tolstoy’s “Resurrection.” They were to be co-stars: Horst playing the arrogant Prince Dimitri; Myriam, the young girl Katouka, whose love Dimitri hopes will redeem him.

Myriam had seen Buchholz in a German movie in which he played a leather-jacketed young punk, and she was furious at the notion that he was to be her partner in the Tolstoy classic. “You mean,” she exclaimed to the film’s producer, “that you’re going to have that beatnik, that Rhineland rock ’n’ roller, play Prince Dimitri?”

Horst himself was not too impressed with the young French actress, either. “Oh, yes,” he smiled, “I thought she was charming and intelligent, but that’s all.”

Somehow, though, Horst’s gentleness and kindness charmed Miss Bru. Myriam loved Paris; she had her own apartment there on the Avenue Montaigne, and Horst loved the great “City of Light,” too. He had hitchhiked there once, when he was about eighteen, with only thirteen dollars in his pocket, and he had lived in the Algerian section for two weeks, on milk, bread and porridge. It had been a delightful adventure. So Horst and Myriam became good friends—only friends—nothing more.

Then, as Horst remembers, “We had to go to the Italian island of Ischia, to do some location shots. It is a marvelous place for romance, this Ischia, and Myriam and I had nothing but love scenes. I suppose that was when we really fell in love.”

When “Resurrection” was completed, Myriam left for Rome, while Horst was scheduled to begin “Tiger Bay” in Wales. The first day he was there, he saw that he could not be away from Myriam another minute. He sent her a cable. “Come to London immediately,” it read. “I am going to marry you December 28th.” They were married exactly as Horst said, in the London Registry Office, on December 28th, 1958. Myriam spoke only a single word of English: it was the word “Goodbye,” which she always used to greet people. Horst himself was having troubles with the language, but he had a better ear than his wife.

“When I first went to England to do ‘Tiger Bay,’ ” he said, “English was a mystery to me. So I had to learn my lines like a monkey. I’d get someone to read my lines to me. then I’d repeat them just as they had been said. I was lucky enough to win the friendship of John Mills and his daughter Hayley. They were so wonderful!

“But,” Horst went on, “they taught me to speak English with a British accent. When I came to Hollywood to talk to Director Billy Wilder about doing ‘One, Two, Three’—this was long before I even started ‘Fanny’—Wilder threw me out. ‘Come back when you can talk the way we talk in America,’ he shouted. So I went away and learned to speak English as I do now.”

And while Horst was learning English, Hollywood producers were learning his name. At first, they rejected it. “That name!” they would chorus. “It’s got to go.” He was called “That fellow Buckles—Horse-Something-or-Other.” There was even an attempt to hold a big contest: Pick a New Name For Buchholz. But Horst refused to go along with the idea.

Today, Hollywood is playing a different tune. Like Horst, they agree the name must stay. Oh, sure, they make jokes like, “He should call himself something simple like Efrem Zimbalist, Jr.”—but it’s Buchholz himself who laughs loudest.

One thing that doesn’t make him laugh is this business of his being “another Jimmy Dean.” Patiently, Horst points out that he does not enjoy being overshadowed by a ghost, nor being forced into a pair of dead man’s shoes. “Look,” he says, “I’m me. Nobody else. I don’t look like Dean, I don’t even act as he did. If I seem tortured or tormented on the screen, or wear a black leather jacket, or even look like a beatnik, that’s what my role calls for. That doesn’t make me ‘another James Dean.’

“For instance, I was born on December 4, 1933—that makes me twenty-eight years old. That isn’t particularly old. But in Munich recently, somebody mentioned a certain young actor who is beginning to make a name for himself. ‘Yes,’ they said, solemnly, ‘this boy shows real promise. He is a young Horst Buchholz.’

“So you see, they do this, this comparing everywhere. But I am no James Dean.”

There was, of course, the way Horst hurtled his white Cadillac convertible across the narrow highways of Europe that helped liken him to Dean. But that car is no more—even the man who all but killed himself recently on a Munich road is no more.

The accident—Horst says a tire blew—happened only a few days after he jokingly told director Billy Wilder, “I’m not going to die like Jimmy Dean.” They found Buchholz crawling beside his demolished car, clutching his middle where a piece of the shattered steering wheel had pierced him. He was in the Munich University Clinic for weeks and almost died. What scars the accident left—scars both physical and emotional—the episode is a closed chapter with him. When the accident is mentioned, Horst’s eyes turned veiled. Dean, they said, had a “death wish”—and that explained the way he drove the Porsche that finally killed him. But Horst? He was soon to become a father; he had commitments for pictures extending over the next few years; he had his Myriam; his parents, his sister Heidi were back with him again.

“You know,” Horst said, “I never really liked that big car. I only bought it because Myriam and I travel around so much. We had to have room for all her trunks and suitcases—as many as fourteen of them,” he laughed, looking teasingly at his wife. “But now I have no car, I don’t know when I’ll get one—and I don’t care.”

Horst and Myriam have an apartment in Paris, a winter home in Chur, Switzerland (they both love to ski) and for their stay in Hollywood, they’ve rented a huge home in Bel-Air. “With an Olympic-size swimming pool,” Horst adds gleefully. And that’s where Myriam will stay until the baby (due next month) is born. while Horst goes off to India to make “Nine Hours to Rama.” For company, she will have Horst’s mother and her own mother. There will be one problem—no car.

“It would be useless, a car,” Myriam said. “I do not do driving. I shall have to be drived.”

Horst almost choked on his coffee, “Driven,” he said. “Not drived!”

Some people who have worked with Horst say that he is “hard to know,” and Horst admits that this is true—at times. “He can be moody, intense and even highly opinionated,” one co-worker declared. “In Marseille and Cassis, when we were making ‘Fanny,’ Horst and Myriam kept pretty much to themselves, or spent their time with Horst’s mother, father and sister, who were visiting them. And he liked to wear those cowboy boots of his—I think he bought about a dozen pair in Mexico while making ‘The Magnificent Seven!’ Maybe he wore them because he thought they made him look taller.”

Other co-workers agree that Horst could be, “not exactly standoffish, but truly dignified.” Yet when he felt in the mood, he could be boyish, even playful. He liked to play games with hats, make funny faces and shadow-box with the camera crew.

When he was in Munich doing “One, Two, Three,” studio people set up a Hollywood-style premiere for “The Magnificent Seven.” There were searchlights, bleachers for the fans, microphones and a red carpet leading into the theater. To give Horst a little “color,” the publicity staff ordered a gaudy, silver-mounted vaquero outfit flown over from Mexico, complete with two six-guns, holsters and bandoliers bristling with blank cartridges. “Horst was like a kid who has just discovered the Christmas Tree,” an observer said. “He couldn’t wait to get into that vaquero rig. And as the people started arriving at the theater, Horst stood in the Street, blazing those six-guns into the air. I know he had the best time of anybody.”

Horst is the first to admit that the pinched, frightened, unhappy boy of those early-Berlin days is no more. “Like any teenager,” he says, “I was at odds with the world. I use to fight, argue with and even resent my father. I knew everything; he knew nothing. Just because my father liked to see me looking nice, I wore the grimiest clothes I could find. Well, that’s all over now. I’ve matured. I like to be well-dressed. I even wear a tie. I’m very, very orderly; wallet in this pocket, cigarettes in this one, small change here . . . you see, everything in its place. My father and I are very good friends now. And my son, our baby must be a he, he will not be the rebel that I was—I hope.”

There is no doubt that marriage to Myriam has changed and mellowed Horst. “He’s so considerate, so thoughtful with her,” a friend said. “He protects her like a little girl. They have such an affinity in their thoughts that often they found themselves making the very same comment at identical moments. Myriam has virtually given up her own career, because their marriage comes first.”

If Myriam is slow to grasp an Americanism, Horst happily translates the phrase into French for her—or tries to. Horst was asked if he enjoyed meeting the press. “I love it,” he said, prompting the comment that he is probably “a ham at heart.” Myriam perked up her ears.

“You are ham?” she asked. “What means this?”

“Oh, you know—ham,” Horst laughed. “It is what we eat.”

“Well,” said Myriam, naively, “if you are ham, I will put you in the icebox.”

“That’s right,” said Horst, chuckling, “and you are going to keep this ham for the rest of your life.”

So, if you’ve been wondering about that unique new screen lover with that unique name, now you know. He’s tousled, human, even perhaps a little flawed. But he’s also, in Billy Wilder’s words, “probably the best young leading man in the world today.” It was Wilder, too, who once said that in making the kind of pictures he makes—“Some Like It Hot,” “The Apartment”—“I am not out to provide messages or reform the world; I just want to force the audiences to drop their popcorn and watch.” And Horst Buchholz—the lover and the name—will make you do just that!

—FAVIUS FRIEDMAN

Horst is in U.A.’s “One, Two, Three” and “Nine Hours To Rama,” 20th Century-Fox.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1962

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments