Tuesday Weld And Dick Beymer

The little motor boat, riding at anchor in the bay, rocked lazily—as lazy as Tuesday and Dick, who were stretched contentedly side by side on the deck. The smooth wood felt good against their backs. Their eyes were blissfully closed against the sun’s rays, lulling them half to sleep. They hardly talked, except once in a while in drowsy murmurs. Suddenly, the little boat tossed—so unexpectedly that it rolled Tuesday over on her side against Dick—almost on top of him. And then, having kicked up and played its little trick, the sea behaved again and went back to its gentle rocking. Tuesday’s first embarrassed reaction was to pull away and roll back where she belonged. But maybe it was the sun, or maybe the sleepy salt air, that made her stay where she was. She couldn’t move—she didn’t want to! Only her hand stirred, coming to rest on his shoulder to steady her against the boat’s rock.

AUDIO BOOK

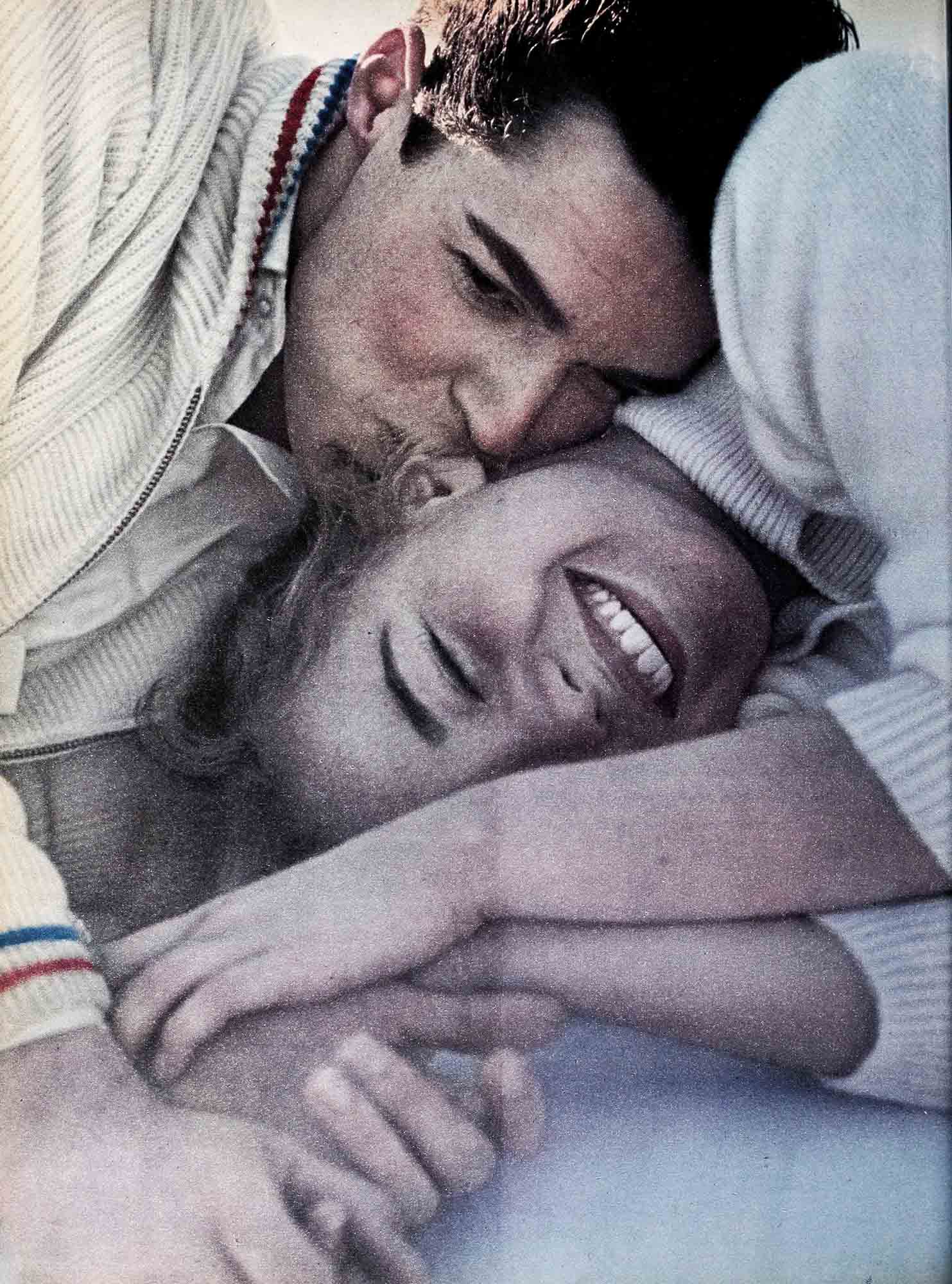

Tuesday felt Dick’s hand join hers, his strong fingers interlace with her slim ones. When he released them, it was to stroke her long blond hair, to gently brush back the silky wisps wind-blown around her face. They lay facing each other now, arms lightly around each other’s shoulders, and Dick smiled, looking into her eyes.

“Nice,” he murmured.

“Oh,” she sighed, “all this dreamy sky, and everything. . . .”

“I meant you,” he said softly, and kissed her fleetingly on the tip of her ear. Then, easily, they both rolled happily on their backs again, and simply laughed contentedly.

Tuesday sighed. “I wish every day could be like this.”

“It will be,” Dick promised. “I’ve got it all worked out with the Weather Man. Tomorrow, fair and warm . . . day after, fairer and warmer . . . day after that . . .”

“Very good,” Tuesday told him approvingly, playing along with the game. “Then starting tomorrow, Mr. Beymer, never mind what we’re supposed to do—we just goof off and zoom out here to the middle of nowhere. And I’ll tell you what,” she said, with mock seriousness, “most times it’ll be just us two, Dick. But, once in a while, we’ll let the others come along. Won’t we?”

“Sure thing—the whole crowd.”

“The whole crowd.” She repeated it—slowly, softly, with a kind of wonder. “The whole crowd,” she echoed again. You’d think they were the words of a song she loved. “Oh Dick,” she exploded suddenly, “I’m so happy! And you’ve done it.”

“I did? I’m glad—but tell me, Funnyface, what’s this wonderful thing I’ve done?”

She looked searchingly into his face. “Don’t you know, Dick?” she asked. “Don’t you know you’re the first boy in my whole life who made me feel I belong . . . right from the beginning?”

The “beginning” started at the airport. “Remember that day at the airport?” he said.

Tuesday groaned and laughed. “How could I forget? I was so late getting to the plane, I was scared stiff you’d all take off and leave me behind in Los Angeles—and they’d make the location shots without me!”

Dick laughed too, remembering. “You were so funny—I saw you from my seat window, running with that big suitcase, hollering ‘Wait for me! Wait for me!’ ”

“That was funny?” Tuesday sniffed. “With that valise banging my legs black and blue every step? I couldn’t get a porter at the last second.”

“Well, I came down and gave you a hand, didn’t I? The way you were clutching that big full blue skirt, I was sure you’d trip up the stairs. So I figured I’d better come take the valise and let you have two hands on the skirt.”

“You were nice,” Tuesday said softly. “I never expected anything like that. You’d never said a word to me on the set.”

“I wanted to,” Dick admitted. “In fact, I was planning to,” he said shyly. “Then the kids dared me to date you.” And, seeing the surprised look on her face, he explained, “Well, you acted pretty standoffish at rehearsals . . . I didn’t take up the dare. I guess I didn’t want to stick my neck out.” He grinned. “But then, at the airport I didn’t want you to break yours, either.”

That was exactly how it had started. Lying on the sunny deck now, Tuesday Weld remembered every minute of the trip the cast of “High Time” took to Stockton—near San Francisco—for location shots. After coming to her rescue as Dick had, it seemed only natural for them to sit together on the flight. Talk came easy and natural; they had this new film in common, and Hollywood to chat about. They got along great, for a first conversation, and there seemed so much to laugh about.

He doesn’t act one bit adolescent or smart alecky, she’d found herself thinking. He seems kind of settled and assured, but not suffocating with the charm bit.

She’d been surprised at her own thoughts. It wasn’t often she met a young boy she felt this relaxed with. With him she wasn’t . . . well, afraid. But that was the wrong word—she wasn’t afraid of boys themselves so much as that idiotic leer she sometimes saw on their faces. That look always told her they believed the mean gossip they’d read about her. And it hurt! She hated that type of boy, the kind who’d just hardly met you but already had you all figured out—his way! Dick didn’t impress her as being like that one bit.

Perhaps her fear had all really started one night when she was only thirteen and going to a high school dance in New York with a boy she didn’t know very well, just from around school. He’d invited her, but when he picked her up and saw the mess of a tenement building she lived in, everything seemed to get all tight and uncomfortable between them. Maybe it was her own painful imagination, but the whole evening he seemed sullen and miles away from her. The little snob, she’d thought bitterly, he hasn’t even got the manners to stick it out with the girl he brought. You’d think I was poison! Maybe all boys his age were goons, going off to dance with other girls and turn on the charm. All she knew was that the evening she’d looked forward to with such excitement, turned out to be one big agony. She still felt sick remembering it.

And then, when she came to California and entered Hollywood High, it hadn’t been any different or any better. How she’d hated the gossip! And the open resentment shown by the other students because she seemed too different in her ways from all of them. Even around the studio, people hadn’t been very easy to know.

“I can’t believe you’re only twenty-two,” she said suddenly. “You seem so mature.” He was pleased and flattered; she saw that the minute she said it and was glad. She found herself wanting to know more and more about him. So, being honest, she didn’t hedge around; she asked straight questions, and he told her of his boyhood in a little Iowa town where his dad was a printer. And how, when he was ten, his father decided to move the family to Los Angeles, where there were more opportunities in his line of work.

“I thought I’d die with excitement at the idea of seeing Hollywood,” he told Tuesday and laughed when she answered, “Not me—I was scared stiff!”

“Well I wasn’t,” he said. “I was all excited to get in. I asked my mother to let me take drama and dancing lessons, and from there I got to TV.” He grinned and said, “I can still see me, every day after school, running all the way to the TV studio, afraid I’d miss something. But I was in luck, that show lasted right up till I was fourteen, and from there on an agent helped me make it into the film studios. So here I am.”

Yes, Tuesday had felt like saying, here you are, and doing fine, but you’re so nice and modest, even about a big part in “Anne Frank” that you make it sound like a little thing anybody could’ve tossed off. And she thought, gosh, Dick Beymer, you are a nice person! But she didn’t say any of it out loud—not then, not yet. They were only getting to know each other. It was like a first date—only better!

Now, months and months later, they were such good friends they could stretch contentedly on a sunny boat deck and reminisce back.

“Remember when the plane landed in Stockton?” Dick asked. “And I said ‘Let’s have dinner by candlelight.’ I did want to have dinner with you, but the candlelight part was supposed to be a joke—to pay you back for the mystery you made of that piece of paper on the plane, with the number 25 on it. You kept looking at it and giggling, and you wouldn’t tell me what it stood for.”

“I still won’t,” Tuesday laughed. “That’s my secret little joke and I won’t ever tell you what it is.”

“So I gathered. And the candlelight was supposed to be mine. Only you took it straight, remember? You said, ‘That would be fun, Dick,’ and you meant it. You were so enthusiastic, I just couldn’t disappoint you.”

“So you asked the waitress to please bring us a candelabra,” Tuesday giggled, “and I can still see her expression when she shrugged and went for it! I guess she said to herself, ‘Crazy movie people. Without candles they can’t see to eat!’ And we were conspicuous—the only two in the Hotel Stockton dining room with candles on the table. But it was fun, wasn’t it?”

His answer came softly. “I got a kick just out of watching you enjoy yourself.” Suddenly he confided, “You know, Tuesday, it was a miracle how we got together on that trip, considering we’re both so slow to reach out to make friends. I like people fine, but rather than take a chance of being turned down, I won’t be the first to approach. And it didn’t take long before I saw you weren’t as standoffish as you seemed on the set—you were only waiting for someone to come up to you and take the lead. So when two shy people make friends on one short plane ride—girl, that’s news!”

That was when Tuesday turned to Dick and propped herself up on one elbow so she could look at his face while she told him the very important thing. “You’re the first boy who ever made me feel I belong to a crowd of young people my own age. You did that for me, Dick, you opened doors I always thought were purposely shut on me, so I didn’t dare open them. I was always afraid. But now I’m not.”

Yes, from that day on he’d been a wonderful friend. He accepted her just as she was. He didn’t screen her, criticise her or try to make her over. He didn’t tell her how to dress, how to put on makeup, or wear her hair. But best of all, the whole while they were on location, he drew her more and more into the young crowd she’d always shied away from out of fear—but he was the first to understand . . . So because they accepted Dick, and he accepted her, they accepted her—and found she was fun.

But the best fun of all was with Dick. Often, when there was a lunch break and the others were gone, she’d go up to the bandstand with Dick and Jimmy Boyd, who was in the picture with them, and they’d play trio. Dick on drums, Jimmy on guitar, and Tuesday at piano, or sometimes doodling on a Chinese flute her mother once gave her. A little ten-cent toy flute, but she clung to it like a kid does to a treasured toy. And this was something else Dick understood about her—that she could swing from sophisticated to childish. That she was an older, maturer person when working, but when the makeup was off and her hair down, literally, she was somebody else—a giggling young girl he knew and liked so much. She could sit with him, deep in earnest conversation about life—or she could run shouting and laughing and battling him for the basketball they were playing with. She could be quiet and grown-up, or she could jump up and down on the trampoline, wild with the sheer physical fun of it. like any girl her age—or younger! Dick understood all this about Tuesday.

And all the while, she was growing in self-confidence. They ate with the crowd one night and, as they walked out and headed back for the hotel, Tuesday felt an impulse to go sight-seeing instead. Just the two of them.

“Couldn’t we go for a walk?” she asked Dick. For the first time in her life Tuesday was feeling the assurance it takes to be the one to suggest breaking away from the crowd.

Hand in hand, they walked toward the city square. “I just wanted to be alone with you for a little while,” she said softly, and Dick squeezed her hand in pleased understanding. They wandered, taking in the local sights and smells. They pressed their noses against store windows, studied people passing on the street.

“Don’t you love wandering and watching everybody?” she asked, turning happily to Dick. He nodded, clearly enjoying her excitement over the world around her, and the glow on her face.

“Oh, there’s a wonderful old, old church,” she cried. “Let’s cross the square and see it close up.” It had weather-beaten red brick walls, but the door was puzzlingly hard to find. They circled it, searching till they came on a tier of windows crisscrossed with iron bars. Then they saw the sign. “City Jail.” They laughed till they had to lean on each other in order to stand up.

Then they did a really crazy thing. Tuesday’s idea. It began to rain and she cried, “Oh wouldn’t it be nice to go for a ride in the rain?”

That was a ride they never forgot. Even now, basking in the sun on a little motor boat, they began laughing over that ride on a dark, rainy night with the two of them listening to the music on the car radio and paying no attention to signs. Until suddenly they found themselves crossing the Bay Bridge—driving into San Francisco!

“Wasn’t that exciting?” Tuesday recalled. “San Francisco is the most interesting city in the world—and to stumble on it like that, was a complete surprise! And, Dick, I crack up every time I think of you saying ‘I don’t know San Francisco, but now that we’re here, what would you like to do?’ and me saying . . .”

“And you saying,” Dick sat up on the deck and did a perfect imitation of Tuesday revealing a great desire “You said, ‘Oh Dick, I have the biggest thirst for orange juice.’ So we scouted around till we found a little orange juice place. How do you like that—I drive eighty-five miles in the rain just so you can drink a glass of orange juice!”

Tuesday jumped up from the deck and stretched her arms way up, contented and relaxed. Dick stood up, too, and started for the boat’s stern to haul up the anchor. The sun was going lower in the sky and it was time to head for shore. Another day was ending—another lovely time to remember.

Before Dick got to the anchor cable, Tuesday ran over to him. On an impulse she threw her arms around his neck and put her cheek to his.

“That’s just a thanks, Dick,” she said. “Thanks for being the way you are—and making me so happy. Thanks . . .” but she didn’t finish the sentence. She didn’t have to. She knew that Dick understood.

THE END

WATCH FOR TUESDAY AND DICK IN 20TH’S “HIGH TIME.” TUESDAY CAN BE SEEN IN COL.’S “BECAUSE THEY’RE YOUNG” AND U.I.’S “THE PRIVATE LIVES OF ADAM AND EVE.” WATCH FOR HER ALSO ON CBS-TV, TUESDAYS, FROM 8:30-9 P.M. EDT., IN “THE MANY LOVES OF DOBIE GILLIS.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1960

AUDIO BOOK