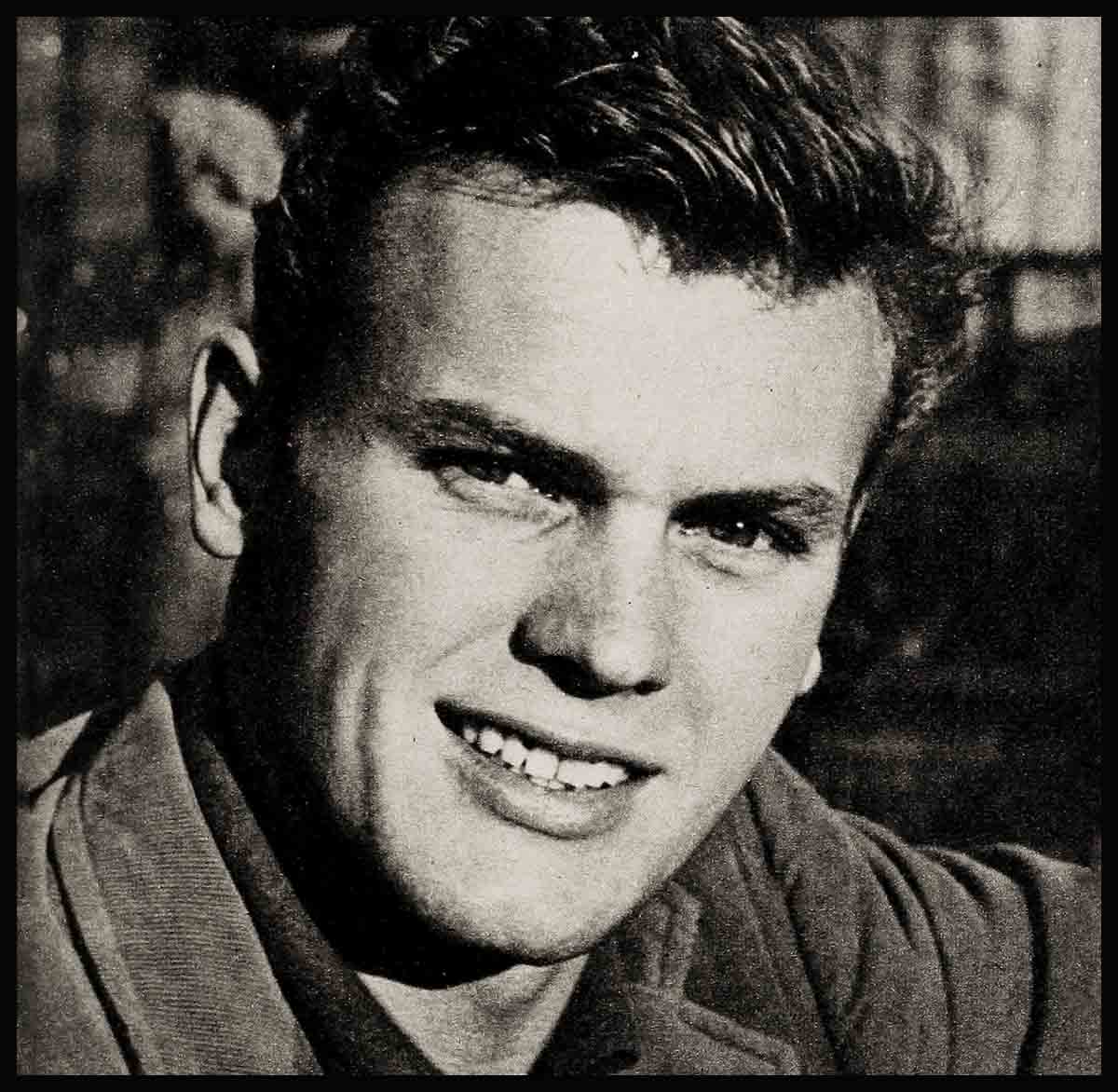

My Everyday God—Tab Hunter

There is a stained glass window in the roof of St. Paul’s in Los Angeles which is a replacement. About eleven years ago I smashed a baseball through the original pane. I was a student at St. Paul’s parochial school and my class was playing ball in the yard during recess. When I saw what I had done the bat slipped from my fingers and I stood there trembling. At the age of twelve, having made my first Holy Communion only a few months before, I had brought the wrath of God upon myself—or so it seemed to me.

You know how boys are. Some of the other kids laughed nervously, and enough of them were so shocked and looked it—that the enormity of my offense was something I had to believe. I watched dully as my older brother, Walt, ran into the church to find the ball and came out yelling to show that he had it. And then I went slowly to tell the priest what I had done.

Never again, since that day, has the church ever been a heaviness in my soul. I don’t remember what words the priest used to make me realize that love, not fear, is the keynote of worship, but in time, the effect of his words was complete. I am not on formal relations with faith and I never shall be. The business of coming to Mass late, and leaving early, and for that short duration being a religious man, has no attraction for me. Instead I live generally conscious at all times, no matter what I may be doing, that I have a spiritual affiliation. I don’t mean that I walk with pious manner or expression. My faith doesn’t get in my way. I just try to live so it is my way.

Maybe I should explain about my Catholicism. When some of my friends have said that I am an “amazing kind of Catholic,” they don’t mean my devoutness. They mean the way I came to enter my church. I like to tell the story because it illustrates so graphically the wonderful and tolerant philosophy of a lady whose outlook on life has always inspired me—my mother. My mother is not a Catholic. She is a follower of Unity. In a sense I was taken from her arms and conveyed to Catholicism while her attention was engaged in earning a living for my brother and myself. When she learned what had happened she uttered no protest, insisted on no change, permitted both my brother and me (it happened to both of us) to consider ourselves Catholics and continue as such. She gave us no reasons, but in the years to come we felt we knew what they were.

My parents separated early after my birth so that I don’t even remember my father. Mother got work as a ship’s nurse with the Matson Lines and had to leave Walt and me (neither of us yet five) with a Catholic family. With Mother away for long periods, these good people felt more than an ordinary responsibility for us; they felt we should have a religious identification and since our lives were so closely entwined with theirs they took us with them to their church.

Later, at a time when Mother was seriously ill, she consented to having us baptized in their faith which was already so familiar to us. To Mother, as I came to realize in time, there is a divine plan to life. The baptism of her children in another church might well be a part of it. She would not interfere.

And so, in what was probably a unique family relationship, we continued to live together thereafter, Mother in Unity, and her two sons in Catholicism. There was no clash. Instead, the fact that she granted us, just two small boys, such autonomy and independence, not only gave us a feeling of freedom we’ll never forget, but more than this, the rich sense of individuality so important as a source of self-respect and well-being.

In Unity the teaching is that thought is omnipotent. Mother would put it to us this way, sometimes: “Thoughts are things. If you think right thoughts, the right things will happen.” I fell into believing her and I have never fallen out. This, added to my Catholicism, worked out into a basis for what I have mentioned before—the feeling that my God is an everyday one, not just a Sunday divinity.

At any time I am apt to pray. If this sounds a little stuffy I should make it plain, perhaps, that to me prayer is not the formal thing others too often take it to be. To me prayer is just being “in touch.” When I drive, for instance, I talk to St. Christopher a lot. If a near-accident occurs I am apt, quite naturally, to speak to him. I guess friends have heard me burst out, “Oh, thanks, St. Chris!” No matter how tired I am at night, I pray—no matter if I am so tired I know I’ll never finish. What better way of falling asleep than in the middle of your prayers? If I see a little raggedy child in the street I don’t go by without a thought, a prayer-thought for her. When I pass a church I don’t keep looking straight ahead as if I haven’t seen it, or as if this isn’t the time for such matters. I turn and look and I say a sort of prayer-hello.

I don’t want to sound naive about this, or childish. What I am again trying to make clear is that I am not one for formal piety—I don’t even like such a picture of myself!—but that I consider that my church is my friend as well as my source of salvation. For instance, I love to go to Lake Arrowhead on a Sunday and attend Mass outdoors at the Shrine of Our Lady of Fatima. But if on a Sunday morning I also want to waterski, and the water is best-for this at just about the time of the two Masses, eight o’clock and ten o’clock, wouldn’t it be all right to miss the Mass?

Maybe you are a little ahead of me and figure that the answer is yes and that is why I call the church friendly. But it doesn’t work out that way. When I was faced by the problem I decided I should not miss Mass. Having made this decision, I was given a helping hand by my friend, the church. I found a small Catholic hospital at Lake Arrowhead where a six A.M. Mass is held every morning for the patients and nuns. The next Sunday there was in attendance at that Mass, held in a small chapel in the hospital, ten patients in wheelchairs, six nurses and one water skier. This was a matter between “friends,” and my friend the church was naturally serving me a good turn.

I don’t want to sound forgiving about myself. I would like to sound forgiving about everyone. I have told lies, I have hurt people and I have stolen. But I have never done it easily and my hope is to make it so much harder that I won’t be able to do it at all. And maybe because I know how much understanding I need, I always want to have understanding in stock for anyone else.

The kindest face I can think of belonged to an old workman in the West Indies who used to shuffle down every day to open the gate of an estate in Jamaica where we were shooting scenes for Isle Of Desire about four years ago. I noticed two things about him quickly—his benevolent look and the fact that his feet were bare and unprotected from the hard rocks and gravel of the path. One day I gave him one of the two pairs of new sneakers I had bought. But next day he was still walking barefoot.

I wondered about it and some of the others in the company kidded me. They said they had heard that my noble looking gate man was one of the biggest drunks in the district, and that he had undoubtedly pawned the sneakers for rum.

“The fact is,” said one of the fellows, “you probably contributed to his downfall, rather than helped him.”

They all laughed and I felt foolish and rather annoyed about it. One of the other men noticed this and talked to me later about it. “You know, you have no right to resent the old gate man in any way,” he said. “You had reasons for giving him the sneakers and nothing he did with them can in any way lessen what the giving meant to you. Now what was it those sneakers had to do—which they haven’t done—that has bothered you? If he is an old man who has had the curse of heavy drinking on him all his life were you going to cure it with your small gift? Did you wish to commit a miracle? And are you angry because you didn’t?”

I saw what he meant, of course. I’ll never in my life again ever give anything to anyone without also giving the understanding that it does not commit them in any way.

Since I need such understanding for myself, how can I deny it to others? I pray that I’ll stop telling lies, for instance. Yet this, as I know, doesn’t guarantee that I will stop. When an occasion turns up in which I get the idea that a lie can help me, out comes the lie, as likely as not. And of course it comes out even though I know that more often than not it won’t help me at all, that, in fact, it will jam me up!

Back in Jamaica, when we were making that same picture, the director asked me two questions in succession and my answer to each was a lie. He asked me if I could throw a javelin and I said yes. He also asked me if I could shinny up a coconut tree and I said yes. I had, of course, never thrown a javelin and had never climbed a coconut tree. About the javelin—I learned one night that on the next day I would not only have to throw it, but hit a bunch of papayas with it. I started practicing and kept at it so furiously that the next day my arm was so sore I couldn’t flip a toothpick, let alone hurl a javelin.

About the tree—that was a mess, too. Talking over some forthcoming scenes with an assistant director, I learned that one was coming up which required me to climb a coconut tree. Again I practiced and again too late. When it was time for the scene I was a very good climber of an eight-foot tree. But the one they showed me shot straight up for forty feet. I hadn’t a chance and they had to fall back on some makeshift handling of the problem which embarrassed me plenty. They filmed me doing my eight-foot climb from the bottom of the tree. Then they chopped off the top of the tree, stood it upon the ground and had me climb that small section, filming me so it looked as if I had climbed all the way.

So I don’t need to get hit over the head to realize I must have a spirit of understanding and forgiveness for others. I need only to review how much understanding I have taken from others all my life. I can even go back to a time in San Francisco when, as a four-year-old, I was a sore trial to my usually understanding brother who was all of five. Wherever his adventurous soul drew him he had to take me, not only because he was supposed to look after me, but because I was such a cry baby in those days I’d get him in a jam if he didn’t. (I continually jammed him up anyway, I guess, because I have a tiny piece of scar tissue just northeast of my left eye where he caught me with a BB pellet one day for “telling on him.”)

My mother had to show a lot of understanding, too. One day Walt and I, still prekindergarten age, wandered away from home and found ourselves down at the Fisherman’s Wharf at nightfall. We had lost our shoes and stockings (or had thrown them away most likely) and of course we hadn’t had a bite to eat. Then Walt got a wonderful idea. Seeing fishermen around he figured they needed bait, so we started digging for worms we could sell to them. It worked indirectly. A man asked us what we were doing and, giving us carfare, put us on the trolley for home.

When I got into my early teens I went horse-crazy. I just had to go riding every day. Naturally I didn’t have the money to ride as much as I wanted to and I got a little sticky-fingered to take care of the emergency. The victim was my mother. I would take loose money from her coat pocket, I would keep the change when she sent me to market and I’d snatch anything that was lying around loose. For a long ‘time this went on without a word from her. Then one day I stole from her pocket-book. That was the end of it.

She sat me down and let me know she had known about my stealing all the time. She named the amounts so there could be no mistake. She said that each time she knew I had stolen she had wanted to mention it, but hadn’t because she hoped I would stop by myself. And she had kept on hoping.

“Today you went into my pocketbook,” she said. “What happens now?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Do you do something about this or must I? I will leave it up to you. What’s the answer?”

Didn’t have an answer for a while. And then-one came to me. I told her I was going to find some kind of job to make the extra money I wanted. (And I did.) Her eyes became gentle for a moment. I knew she was smiling inside and the moment had a certain wonder in it for me—how quickly we had gone from desperation to hope again, and how quickly her love for me had wiped out the memory of my ugly thefts!

A nice girl, my mom, and a nice viewpoint she has helped give me. She had a right to be bitter about many things in her life and she never was. How could I ever be? She used to see right through our poverty and hard times toward something I could tell must be wonderful to make her eyes light up as they did. And now I know what she saw. Another day and another place—where we would belong forever! I wouldn’t want to be here now if I couldn’t have been there then!

THE END

—TAB HUNTER

(Tab Hunter can be seen soon in Warners Battle Cry.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1954