He “Flipped” On A Dream

In the darkened, ominously quiet projection room, the screen came to sudden, noisy life. “Spencer Tracy and Robert Wagner in “The Mountain.’” There it was, in bright, gigantic letters.

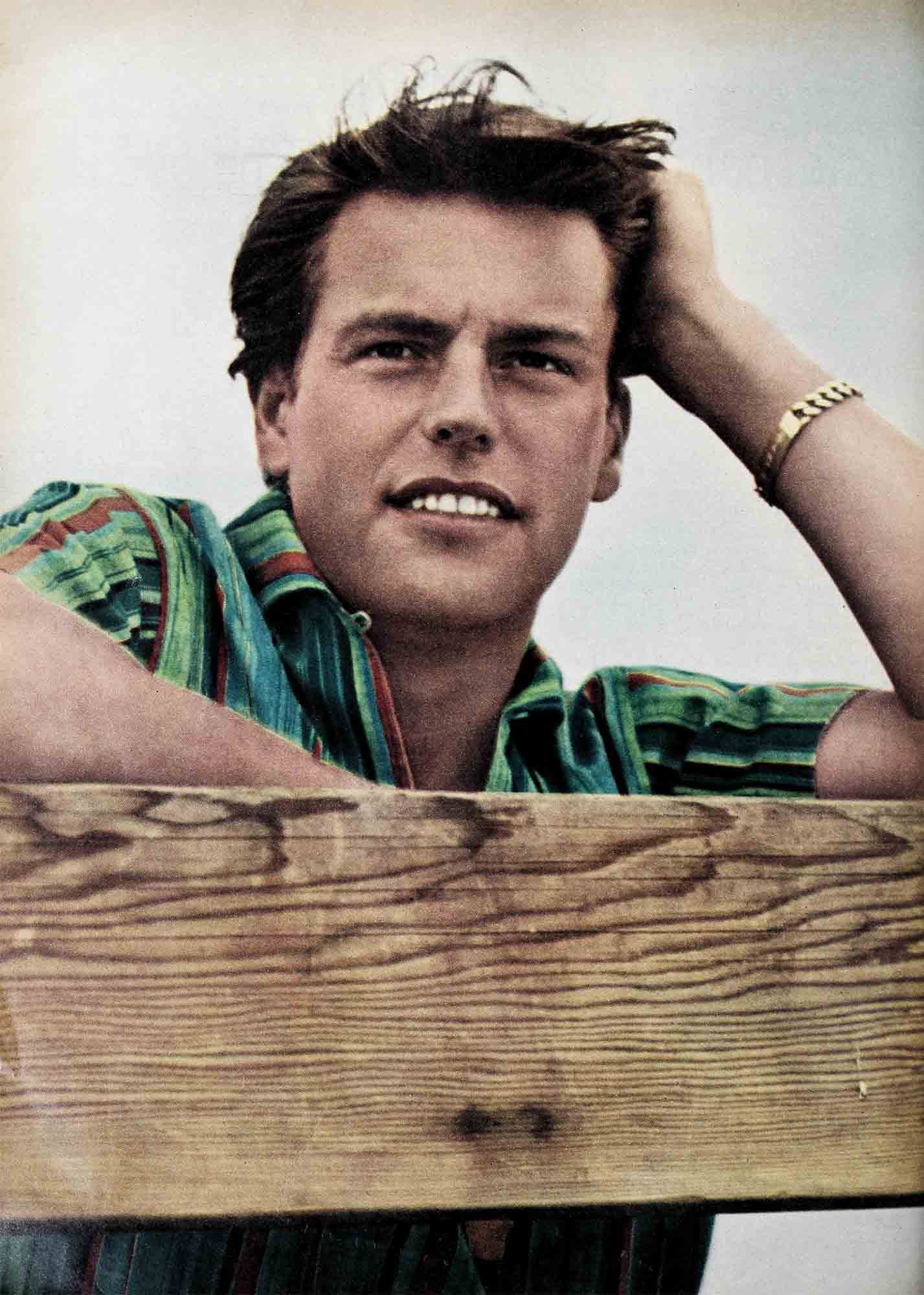

The young man whose classic profile is known to millions of moviegoers turned and twisted and slumped restlessly in his chair as he stared at the screen. Watching him, you found yourself remembering the first time you saw Bob Wagner, in his very first interview. He was the kid who was solid stardust from head to toe, impatiently dedicated to becoming a top movie star.

“I love this business—the whole thing,” he’d said then. “I’ve always been a movie fan anyway, and I know now, this is what I’ve just got to do.” He’d turned his back on a safe future in business for a chance in the magic world of celluloid, and he was sure he’d never be sorry. “This is a terrific business,” he’d said, and still says. “I like the people—they’re terrific, too. And the way I figure it, if I work hard—well, who knows? But time will tell. . . .”

And time had told—is telling now.

Bob had always been a great fan of Spencer Tracy’s. Not only of Tracy’s acting, but of the man, himself. He used to stop by the Riviera Club on his way home from school every day, and watch Spence playing polo. And, while still a kid, he’d stood in Tracy’s footprints in the forecourt of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, excitedly trying them for shape and size.

Now, up there on the screen, he was making his own footprints to fame.

When the lights went on again in the projection room, Bob was the first one out the door. “All those people—I had to get out of there,” is his way of explaining it. “They all feel they have to say something. And what are they going to tell you? What can they say? Nobody’s going to tell you what they really think.”

The restlessness apparent in the projection room does not disappear. A dream has come true, and now Bob Wagner’s thoughts are bent on the next dream. He’s never satisfied. No one can kid him, for he remembers others who allowed themselves to be satisfied, and kidded.

“I’m sitting in a dressing room right now that once belonged to two other guys. They were big guys—then. You keep remembering these things.”

Although he’s still the youngster with the brightest red socks and the breeziest speech, Bob tells you seriously that just being in motion pictures “doesn’t gas me any more.” He breaks out with “Holy Toledo!” from time to time, and it’s “Happy days in Dixie!” when everything’s going great. At twenty-six, he is equally dedicated to the magic stuff dreams are made of—and to the tough, resourceful stuff of which actors are made today.

Just to be a movie star is no longer enough—nor is playing it safe as a personality, for commercial purposes. Bob Wagner knows what he wants, and he knows the complex problems, the inevitable delays that stand in his way of getting there. He says, with concern, “Today’s market is a commercial market. You’re only as good as your last picture—and the money it makes today. You want to be an actor—and they tell you that’s not commercial. Where do I go? I don’t know. . . .”

One thing Bob does know: his decisions, right or wrong, must be his own, however much he can control them. “To be a success, one must be an individualist. It’s up to you to decide, to do your own thinking.”

Getting co-star billing in “The Mountain” might have gone to his heart, but not to his head. This, Bob assures you, was a gift on Spencer Tracy’s part. “Spence gave me that. He told me be- fore we started that he wanted to give me billing. Spence got me in the picture, too,” Bob enthuses. This is the thing that really overwhelmed him. “The part’s the thing. I wasn’t concerned about the billing. I don’t think you can measure success by that. But I do believe that, if a man like Tracy asks you to do a part in a picture in which he’s personally interested, you can’t be paid a finer compliment. To me, that’s a truer measure of success than anything else.”

When they started to work in “The Mountain,” Bob tried to thank Spence, to tell him how indebted he was to him. “There’s only one way you can pay me back,” Tracy told him. “Do your job. Put everything you’ve got into every scene—no matter how small it is.”

Inspired by Spence’s faith in him, Bob had no fear in co-starring with “The Pro,” as he affectionately calls Tracy, in virtually a two-man picture. “Spence is so great to work with, so believable, he gives you confidence. He has a great feeling for whether something’s right or not, and I felt if what I was doing in a scene wasn’t right, Spence would tell me.”

Spencer has told associates that he con- siders Bob Wagner potentially a very big star and “the best of the younger group.” Director Eddie Dmytryk, who also directed Bob in “Broken Lance,” says that in addition to his physical attributes, his personality, and proving himself at the box-office, “he’s developing as an actor at quite a rate!” Director Walter Lang—who was the first to realize his potentiality when he gave Bob the poignant part of the shell-shocked soldier in “With a Song in My Heart”’—rates his future as “just unlimited.” And Gerd Oswald, who directed “A Kiss Before Dying,” in which Bob gave a fine performance in a very difficult part, heartily agrees.

“There’s a multitude of talent there,” Gerd Oswald says now. “Bob’s so sensitive and intelligent. You’ve got to reach him, but once you really get to him—he goes!”

Although there were skeptics who were sure Bob would be in over his depth in “A Kiss Before Dying,” director Oswald had no doubts whatsoever. Nor did Mona Freeman, who made the original test with Bob. As she says, “Bob was pulling for me to get the part of the pregnant girl in the picture, and he wanted me to make the test with him. It was the scene just before he pushes the girl off the roof, and he was wonderful. The way he shoved me off the roof, he was really frightening!”

Although several other names had been mentioned for the role, Gerd Oswald insists “the part was always Bob’s. He wanted to do it, and I had a hunch he would be great. I’d seen him in ‘Broken Lance,’ and I’d liked him so much in that. Bob also had the charm the part demanded. The boy had to be up-beat, in contrast to the down-beat way he treated people in the picture. He had to be personable and likable—otherwise he couldn’t get away with it. Bob proved to be everything Id anticipated in the part,” Oswald adds warmly now.

As for Bob, nobody realized more than he, the criticism he would be inviting and the risk he would be taking with his fan following. And nobody was surer that he had to take that chance.

The Bob Wagner who’s appearing on the screen today is no stranger to those who’ve really known the boy behind the breezy veneer. They have long been acquainted with his sensitivity, his warmth and loyalty—and his lasting gratitude for any faith and help along the way.

Richard Widmark is one of those who know the real Bob Wagner. From the beginning Widmark was impressed with the genial eager kid who seemed eternally underfoot and always full of questions. And it was Dick, as Bob has said before, who gave him his first close-up on the screen. With a bit part in “The Halls of Montezuma,” Bob was just one of many Marines going over the hill behind Dick in a scene. Widmark noticed that Bob was going out of camera range before he even got in. “Look, kid,” he told him, “slow down, or nobody will ever see you. Next time take your time and follow me.” As an awed Bob said later on, “I was between Dick and the others—and the camera was full on me!”

Dick, however, shrugs off any mention of his helpfulness. “It’s easy to go out of your way for people, if you like them—that is, if I ever did go out of my way. But Bob’s an unusual kid in this business. You can tell when a kid’s out for a fast buck—and Bob was never taken in by any of the hoopla. He wants to be a good actor, and he’ll be a very good actor. He’s such a likable kid.”

Not long ago, it was rumored that Widmark had been injured in an accident, on location in Arizona. Although everyone tried to reassure Bob the report was not true and that Dick was fine, he couldn’t stop worrying.

“But I heard it over the radio,” he insisted. “They just said—”

“Look, Bob,” they told him, “the publicity man just flew back from there. Take his word for it, Dick’s perfectly okay.”

But finally, Bob just had to hear it first- hand. That night he put through a call to Widmark, in Sedona, Arizona. “It was 10:30 p.m. there and there was no phone in the bungalow where Dick was staying. The girl had to call him to the office phone. He had a very long walk in,” Bob laughs now. Widmark’s voice was tired and thick with sleep. When he realized who was calling he became thoroughly alarmed. “What’s the matter, Bob? What’s wrong?”

“I heard you were in an accident,” Bob began lamely.

“No, Bob. I’m really all right. Weedy’s all right,” he said warmly, and wearily, and wended his way back to bed.

This is the Bob Wagner that children in the hospitals he visits know—and they really get through to him. Frequently, without fanfare, Bob visits many children’s hospitals and the hushed wards in veterans’ hospitals that few people ever see. For his role of the emotionally confused GI in “Between Heaven and Hell,” Bob had only to recall the many faces, indelibly etched on his brain, that he has seen so often in veterans’ hospitals.

“But kids can do it to you, too,” he says thoughtfully, remembering some who really have. “The children who are mental cases, they get you. An adult may sense that he has a mental problem, but the kids don’t realize what’s wrong with them. They’re so happy, and when you see them, it really cracks you up.”

This is quite an admission for Bob, for it has never been easy for him to show emotion, off-screen. And sometimes it is hard for others to get through to him. At times, Bob is still the boy who went into motion pictures a few years back, the boy who seemed somewhat shy and insecure, in spite of his eagerness to shoot for the moon. A great deal of that shyness still exists, as does the star-struck attitude, even though he’s now a star. He was amazed and impressed, for instance, at the reception he received in Europe.

“Monsieur Robert,” as the French fans called him, was pretty overwhelmed by the fact that he was even recognized over there. “You know how far the medium of motion pictures reaches,” Bob says now. “You’ve heard from others it’s that way, but Holy Toledo! You still don’t believe it. And when you’re swept up in it, it’s pretty fantastic. One day I was standing in front of the Are de Triomphe, taking pictures, turning my camera this way and that figuring out angles. Suddenly I looked up and found myself in the middle of a mob of people, all with their cameras—taking pictures of me. It’s a funny feeling. I can’t really explain it.”

In Honolulu, it was pretty much the same story. Recently, when Bob went to the Islands to do some background shots for “Between Heaven and Hell,” he was loaded down with so many leis he felt like a walking float. That is, until he met up with an old friend from back home, Brother John, a priest who’d taught Bob when he was attending Saint Monica High School. Brother John teaches at St. Louis College in Honolulu now, and Bob immediately got in touch with him. “When I called him up, Brother John wanted me to come over to the school and speak to his students. I was a little embarrassed at the idea. I could just imagine them saying, ‘Look at him—wise guy. Who does he think he is?’ But Brother John really broke the ice for me,” Bob grins.

“You probably know who this is,” the priest said to the assembled student body. “I had him in school. He wasn’t the best student I had—but he pays more taxes than any student I ever had.”

That he does. Yet, if you ask Bob what sense of fulfillment he’s gotten out of what he’s done in motion pictures, he will tell you sincerely, “None really—yet.” He knows there are important days of decision ahead of him, just as he knew the crucial one that’s behind him now—that of Wagner the-actor versus the proven personality, and the inevitable risks involved.

“I was criticized by certain fans—and by some in the business—for taking ‘A Kiss Before Dying,’ ” says Bob. “Fans, particularly American fans, are great hero-worshippers. They like the flamboyant type of parts. If you’re—well, gifted with a certain lucky quality that makes fans like you, you have a tremendous responsibility to them. You don’t want to let them down or spoil any ideas they may have about you,” Bob says earnestly.

“On the other hand, I felt it was time for me to do a complete switch on the screen. And when a role such as ‘A Kiss Before Dying’ or ‘The Mountain’ comes along—parts you feel will give you some sense of satisfaction—then I think you should take it. Not that I want to do many heavies. I don’t. I just want good honest parts.”

In “Between Heaven and Hell,” Bob has another challenging characterization in the role of a young emotionally confused GI who matures in the Army. And coming up is the title role in the re-make of “Jesse James,” with Jeff Hunter co-starred as Frank James. “Lord Vanity” is another slated for the future. And, to top it off, Bob recently plunged into the recording field with his Capitol disc of “Imagination,” which reveals an appealing voice together with plenty of the Wagner personality. Since his only previous experience consisted of ad-libbing a chorus over some friendly piano, Bob’s pretty intrigued and excited about this.

But then, this is true of every phase of the profession in which he insists he’s been “so lucky.” As Bob says, his career is his life. Eventually, he hopes to have his own production set-up, “and participate in a picture from the screenplay right on—all the way through.”

Admittedly, he hasn’t played a game of golf in seven months, explaining, “I’ve decided you can’t be a good golfer and be a good actor.” He’s thought of getting a fishing boat, “but with the pictures com- ing up, there wouldn’t be any time to fish.” And he no longer has any plans for buying a house. “If you have a house you can’t just shut it up, you have to use it,” he says—and where’s the time? Far more exciting to Bob are the backgrounds and the changing worlds of the characters he portrays on the screen.

Recently, Bob signed another year’s lease on the attractive two-bedroom apartment near his studio, and he’s even taken in a couple of roomers. “Birds,” he says, of the chirping from the chimney of the flagstone fireplace. “They build their nests there at this same time every year.” He has a cleaning woman come in twice weekly and he’s completely uninterested in any domestic details.

Marriage still seems as far away as it was for the boy whose whole heart was devoted to this exciting new world. As he would say then, “I want to be successful first. You know, have a future and really know where I’m going.” And he earnestly says now, “I don’t want to get married until I know whether I’ve really got a future in this business or not.”

Whether he has a future in this business or not—only Bob Wagner would still wonder.

“There’s Someone Upstairs who guides you,” he concludes. “In my belief, He takes care of your life and He puts you in your place.”

During the past year, Bob’s “place” has become the all-important plateau in his career. He’s had a look into the “Promised Land,” and the Robert Wagner you know has dedicated himself to belonging—and saying—there.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1956