You Were The House Guest Of Sonny Tufts

If you were a house guest of Sonny Tufts, you’d learn more things about an original way of life than you’d ever thought of before. You’d also learn that when you saw the giant Tufts couple out of an evening and said, “There’s the most sophisticated pair in town!”—how wrong you were! But wait—let’s start at the beginning.

You have no idea of staying overnight when you start. You are merely going to drop in of a Sunday afternoon. as all their friends do. You therefore get into your car (there’s no way of reaching the faraway Tufts house except by car) and you begin driving out of Beverly Hills up Cold Water Canyon—noticing on your way up the Canyon the homes of George Raft, Paulette Goddard, Olivia de Havilland, Ginger Rogers and Harry James and Betty Grable.

On one of the highest mountain ridges, you come to a sign that says “Hidden Valley,” and here you tum down a pot-holed bumpy road into one of the loveliest little valleys in America. Birds sing in its trees, crickets chirp in the grassy hillsides that form the valley and in the midst of its tranquility are only three houses—each entirely hidden from the other. The one looking toward the entire valley is the Sonny Tufts home.

You turn in through stone gateposts to a circular driveway which winds right through the structure of the house, dividing it into two parts—the big main part, and the small wing enclosing the playroom and maid’s room. The house is two-story ranch style, maroon-colored (exactly matching in color the one Tufts car, which is a convertible); its irregular shingled roof is weather-beaten brown, and its windows and doors are edged in sparkling white. On a fieldstone veranda stretching almost the length of the main house-front are several old-fashioned rocking chairs, and in one of these is Sonny’s wife Barbara, sewing on a loud plaid shirt for her husband.

Barbara is one of the few women in the world who deserve the words “striking” and “stunning.” She’s a strapping young woman in her middle twenties, with gleaming black hair parted in the center and drawn into a big knot in back. Her eyes are green and she has a warm, generous mouth; and she’s dressed in black slacks with a smart red jacket and red sandals to match.

As you park your car near an old wagon wheel propped against one of the thirty Tufts orange trees, Barbara sees you and rushes forward, yelling into the distance for Sonny. At once the whirr of a lawn mower stops and around the comer of the house comes Sonny himself at a lumbering run.

His size always amazes you. He’s one of Hollywood’s biggest men—he’s six feet four, he weighs 210 pounds, and somehow you never get used to the brightness of his yellow hair and the blueness of his eyes. But here he comes now at a gallop, with his famous grin flashing for your benefit. He looks like anything but an ex-night club singer from New York—he looks like California incarnate, in a brown and white checked shirt, brown slacks and Mexican huaraches thrust on his bare feet. He gives a cheerful yell at sight of you, and then you find yourself out of your car, surrounded by the Tuftses and their animals.

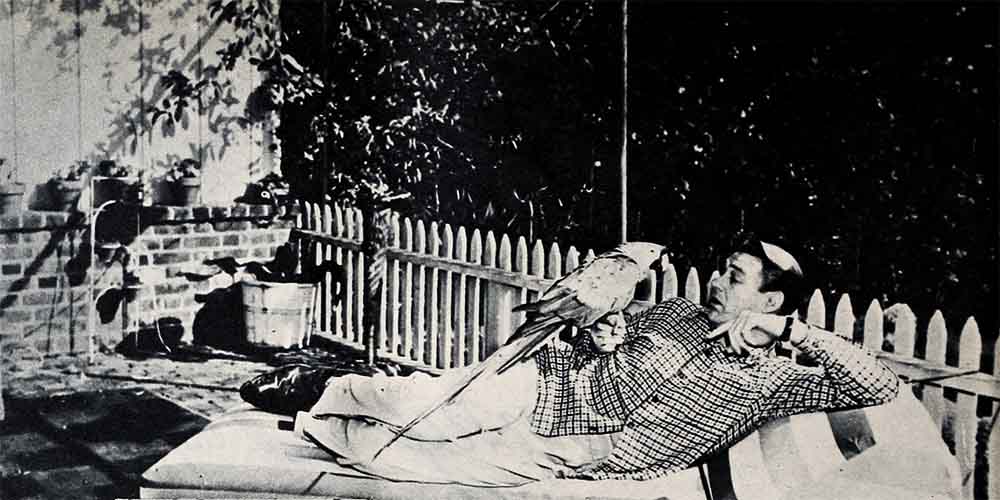

And what animals! You fully approve of the two French poodles who are now jumping all over you. Coco’s a prize-winning poodle whose color is “apricot with silver” according to dog experts, and Dash is black, and both are clipped in that puffy fashion that makes French poodles look like ridiculous big toys. But what you don’t approve of is something that flies up, squawking, “Hello! Hello!” and settles violently on Sonny’s shoulder—a huge fire-engine-red macaw the size of a healthy hen. This creature is Waca, who has been part of the family since 1938. He lives in a big aviary in the garden, but more than often he’s flying behind Sonny’s lawn mower of a Sunday; and nearly every evening he’s crawling up and down Sonny as if the big actor were a tree.

But now Sonny, Barbara and Waca are escorting you inside the house. They are both talking at once about the eight-room house—the first they ever owned in the seven years of their marriage, and they adore it. Writer Director Billy Wilder sold it to them a few months ago, along with its three and one-half acres of up-and-downhill property, 130 different types of trees—and thirty chickens and six mallard ducks! But as you walk through the Dutch-door from the driveway into the main room downstairs, you forget all of their chatter in the sheer pleasure of looking around you.

You’re in a great big L-shaped room, the floor of which is covered in tan woven carpeting. The walls are irregularly sectioned, with parts papered in pearl gray wallpaper while other parts are wooden paneling, painted in the same pearl gray tint. The leaded windows have dark green drapes on either side of them—but none of this you notice at once, because your eye is so distracted by a dozen fascinating things in the room. You see two stunning porcelain lamps—the bases decorated in little pastel blossoms and butterflies. It isn’t until you’ve studied them closely that you realize both of them are chamber pots, carefully painted by Barbara’s hand. “I liked their shapes, so why not use them?” she laughs when she sees your astounded expression.

But that’s not all, by any means. Beside the big radio-victrola you see a small screened-in aviary—smaller than Waca’s big one outdoors but still an aviary . . . and inside it is a gray parrot-like thing which, Sonny explains, is a cockateel. It chatters incessantly in bird language until Sonny finally yells, “Keep quiet, Stinky!” To your surprise, it falls silent.

Meanwhile, you’re staring in delight at the big fieldstone section in which the fireplace is set above a raised fieldstone ledge.

“You two chat, while I get our late Sunday lunch ready,” Barbara tells you—for the Tufts house has no servants. She disappears, and Sonny (with Waca lurching from one of his shoulders to the other) proudly shows you the rest of the room, from a sitting position on one of the loveseats in front of the fire. Studying them, you realize that they are a four-section circular couch,which Barbara divided into two matching sections; they face each other over a big square low table—once a library table, but with its legs shortened to coffee-table height. “Barbara,” Sonny tells you, “upholstered these loveseats herself.”

“Chow!” Barbara calls now, and you and Sonny parade into the dining part of the big room and sit down at the dainty mahogany table. Two comers of the room contain plate cabinets lined with truly rare China. But by now you’ve stopped observing and are diving into your luncheon—which consists largely of a mixed green salad, flavored with a delicious French dressing. A bowl of apples is also on the table, a bowl of walnuts and a plate of cheese. This, with a pot of coffee, is lunch. You devour it, trying not to smack your lips over the completely French feeling of the food; but then you can’t help asking if this slight meal is filling enough for giant Sonny.

“Enough?” says he, mildly surprised. “This is all I ever eat—salads. Learned to like this kind of a meal in France, and can’t get over it.” Thus you find out that the great blond hulk eats like a bird—with desserts and between-meal snacks strictly out. Food has no fascination for him. Swimming has, though; and during lunch he and Barbara enlarge on their dream, which is to build a swimming pool someday complete with a baby seal, to which Sonny could teach tricks. “We like strange animals,” he admits, grinning, as your eyes widen over the seal news. “Fact is, ever since reading ‘The Yearling’ I’ve been thinking how much I’d like to get hold of a pet deer . . . and I’m not kidding!”

After lunch, the three of you carry the plates back into the kitchen and together wash and dry until the kitchen is immaculately neat again. It’s a divine kitchen anyway—a cheerful, sunny big room with white wallpaper dotted with scenes of farms and countrysides, and with the floor done in red linoleum tile. On one wall hangs a blackboard with messages scrawled on it: “Bill Irish called,” “Red Cross ball game at 1:30 at Sawtelle—Sonny to throw opening ball,” and so forth. Here they jot down all phone or other messages for each other.

The peaceful kitchen fades from your mind as you trail Sonny and Barbara outdoors again to greet a sudden rush of arriving guests—actresses Ella Raines, Leone Sousa, Gail Russell, Barbara Britton; actors Alan Ladd (and Sue), Turhan Bey, Billy de Wolfe and the Bill Bendixes. Barbara and Sonny lead them gaily into the playroom.

It has tan carpeting, a brick fireplace, and rough barn-walls painted apple green. There’s a long window seat of red and green linen and a red leatherette bar (made from start to finish by Barbara), with four ordinary kitchen stools in front of it painted green; there’s a baby-grand piano, with Sonny’s drums behind it and two of his many guitars—as well as a huge guitar belonging to Roy Rogers, who forgot it during his last visit. Sonny’s mad for drums, especially for the big one given him by Bill Bendix last Christmas; so from now on he divides his time between drumming, singing and playing at the piano and bartending. Meanwhile, most of the group settle down happily to listen to him entertain—they particularly want him to sing “Egyptian Ella” over and over.

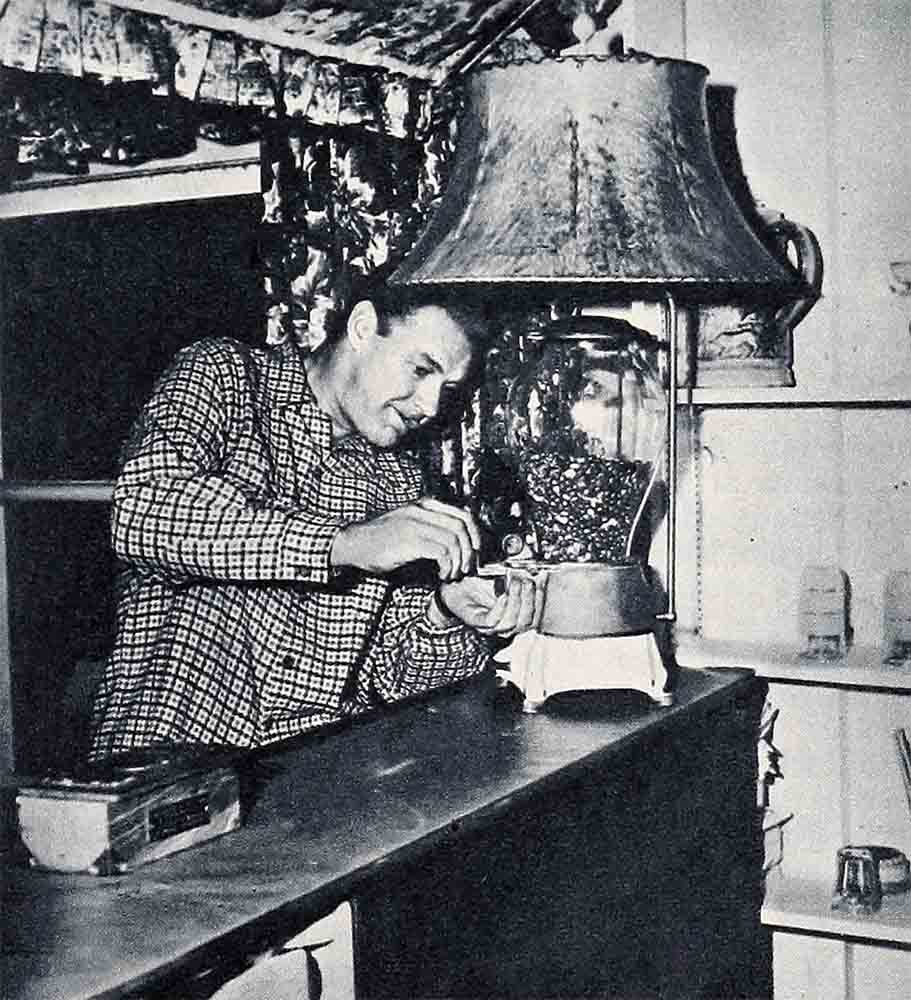

You listen, with your foot tapping; and presently your eye lights on another of Barbara’s fabulous lamps. This one is a peanut-vending machine full of peanuts and topped by a lampshade. Then there are French wooden shoes that look as if they’re walking down the wall, with ivy trailing out of them.

The party goes on until early in the evening, when Barbara rustles up a huge spaghetti dish and another of her luscious salads. Then everybody pitches in to eat it . . . out on the brick terrace. Around nine o’clock everyone goes home; for this is a crowd of actors and tomorrow’s camera will wait for no one.

Then you and Barbara do the dishes, while Sonny sits astride a kitchen chair nearby learning his script for tomorrow’s scenes. Sonny always learns his dialogue while Barbara works in the kitchen.

When his lines are learned, he grabs a copper pan and a spoon and does some quick (and very good) drum routines. Then Barbara cues him on his lines for the next day, after which the three of you go out to the veranda and sit for a few minutes looking down the valley, listening to the evening symphony of frogs, crickets and coyotes . . . for a very few minutes. By that time you’re all sleepy. And you all troop off to bed . . . you having just decided to take them up on their suggestion that you stay overnight.

Upstairs, you find to your discomfiture that you’re going to have Barbara’s room—because, though there’s a guest room downstairs, it’s one of the rooms that Barbara hasn’t yet furnished to her satisfaction in this new house. So they’d rather put you in Barbara’s square, gay bedroom with its sloping ceiling and its tiny marble fireplace. The wallpaper is white with quaint nosegays of rose and maroon blossoms; and there’s a cedar chest, a walnut double bed with a pale green spread, and a chaise-longue with a white fur thrown over it . . . but none of this is finished yet, Barbara tells you.

Sonny has his own yellow-tiled bathroom, but he doesn’t like it so he shares Barbara’s . . . and so do you! You love her dressing room, which is a fluffy combination of red and white; and on her frilled dressing table are two pictures of Sonny with the two inscriptions on them: “I love you, Baba—Sonny,” and “To my beloved Baba—Sonny.”

“Wanna see my room?” Sonny asks boyishly now, and even though Barbara protests that it isn’t any more finished than her room, in you go. His room is almost Spartan in its neatness. A mahogany dresser holds some after-shave lotion, and a wooden paddle from his days at Yale in the DKE house with the legend burned into it: “Sonny Tufts from Tink Carey.” There’s also a picture of his brother David in his uniform as a lieutenant commander. On his chest-of-drawers are only three objects: A pair of cowboy boots with silver trimmings, flanking a stunning picture of Barbara dressed in Spanish costume. On the wall are two graduation diplomas, one from Yale, one from Exeter, and both made out in Sonny’s real name: “Bowen Charlton Tufts III.”

Now he guides you through Barbara’s sewing room, and all of Barbara’s sewing equipment from machine to wire dress form is here. Yes, Barbara not only paints china, cooks, cleans, gardens and upholsters, but she also makes all of her own clothes. She has even made plaid shirts for Sonny; and his favorite pair of slacks came out of her sewing machine. Sophisticated? Well, hardly!

Sonny’s day begins long before you wake up the next morning, with a shower in which he invariably sings “Accentuate The Positive.” By the time you yawn your way downstairs, Barbara has made his breakfast, and has driven him to Paramount Studios because Sonny hates to drive; and now she’s back hard at work planting water hyacinths in two big Chinese cooking pots sunk into the side lawn.

You spend most of the morning with her an hour of it in the sunny breakfast room off the kitchen. You learn that Barbara dresses in black and red for Sonny, who loves those colors on her; that every time she decides to cut her long black hair he changes her mind for her; and that Sonny’s own wardrobe is mainly lumberjacks and wool shirts in blue, with slacks. He wears these clothes to work and on the long hikes he takes over the hills of a Sunday morning—when he walks to the mile-distant reservoir and meets a small boy named Pete, whose father takes care of the reservoir; and together the two hike miles of hills. You learn that both Sonny and Barbara love records, and that they have a big collection now—opera music for him, Spanish dance music for her.

You know that Barbara was born in Los Angeles and her maiden name was Barbara Dare; and he was born three thousand miles away in Boston. You know that Sonny’s father was a banker and director of public utilities; that his grandfather founded Tufts College—and that Sonny decided in prep school to start a band instead of a brokerage house, and did! You know that he continued his band playing several instruments and also singing, at Yale; and that he majored at college in anthropology!

You know that he made twenty-five round trips to Europe with his bands before he settled down; and that he spent six months in France and then two years in New York City seriously studying voice for the operatic stage. You know that during that time a friend led him to the apartment of Barbara Dare (who was herself in New York studying Spanish dancing for the stage)—and that a year later they were married. You know that marriage brought him Waca as a wedding gift from Barbara; and it also brought him enough responsibilities to forget operatic dreams and begin singing in Broadway shows (“Who’s Who” and “Sing For I Your Supper”) and in night clubs such as the Glass Hat, the Famous Door, the Beachcomber, and Palm Beach’s Whitehall. You know that a very rich Yale friend, Alexis Thompson, finally decided the big blond singer should get a break in Hollywood—and paid his and Barbara’s way out to Hollywood for a screen test. You know that the test took, and Sonny found himself a couple of days later in “So Proudly We Hail,” “Government Girl,” “I Love A Soldier,” “Bring On The Girls,” “Here Come The Waves,” “Duffy’s Tavern,” “Miss Susie Slagle,” (and coming up) “Too Good To Be True,” “The Virginian” and “The Well-Groomed Bride.”

You know that Sonny loves swimming and spear-fishing—and skiing, and the studio won’t permit that because once he did a high dive off a sixty-foot snowbank and broke his pelvis. You know that he hates telephoning, and that he reads every single comic strip printed in the Los Angeles papers; and that he loves acting in movies more than life itself; and that some day he and Barbara want to make endless trips from Hollywood to France. You know that they are filmdom’s only non-gin-rummy players—that in fact they’ve never picked up a deck of cards in their lives; and that once Barbara had a gown shop of her own; and that this couple have one of the most interesting backgrounds and a collection of the most interesting tastes in Hollywood.

You also know that the next time they tell you to drop by of a Sunday, you’ll not only come a-running . . . but next time you’ll be smart enough to bring your pajamas along, just in case!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1945