He Lost His Shirt And Became A Star—Richard Egan

“The toughest thing a guy can learn when he’s twenty,” Richard Egan said, “is that he’s not as brilliant as he thought he was when he was sixteen. It’s still tougher, when a few years later, he has to face the fact that maybe instead of being the biggest success in his field, he may end up being its least-known flop.

“And that’s just the state I was in a few years ago. It was the absolute low point in my ambitious life up till then. I certainly wasn’t the boy wonder any longer. In fact, I began to wonder if I were even an actor. It was then that I decided to give up all thoughts of acting and go back home to my folks in San Francisco and try something easier.

“Back home I tried to forget acting—for all of five minutes. But I ultimately came back to Hollywood. I had to. Acting has always been my goal, it always will be. And I knew that while I faced lean years ahead, I felt that maybe I’d have a chance, during those lonely, frustrating months, to sweat off some of the fat around my waistline and a little more off my big head.

“When I came back to Hollywood, I returned humble and eager. I was anxious to take any part offered me, no matter how small it was, no matter how unimportant. All I hoped for was that I might be able to stick around so I could learn enough to be worth something—someday. I knuckled down to work. For a long time it was all work and no play, but it was worth the effort; it paid off.”

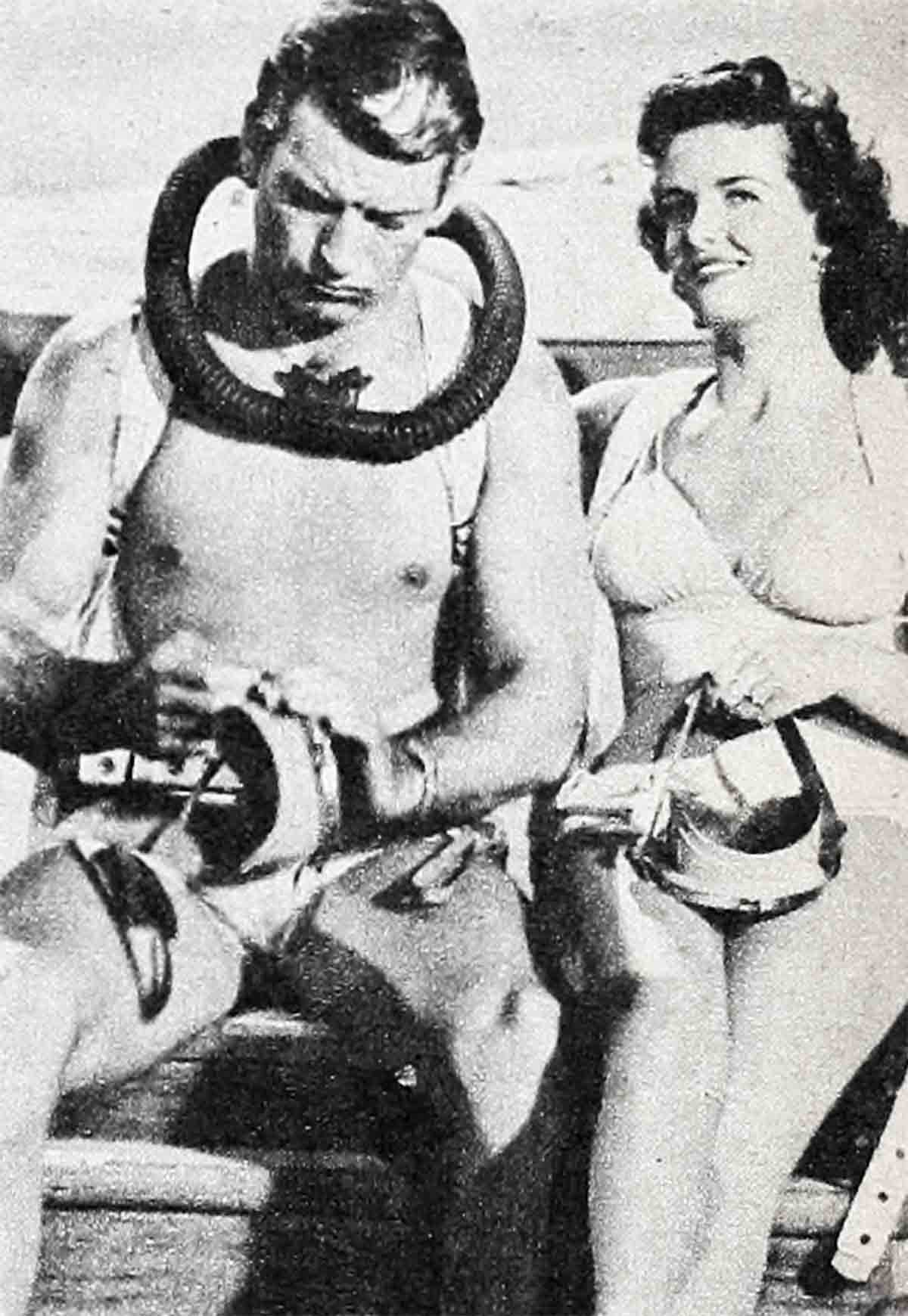

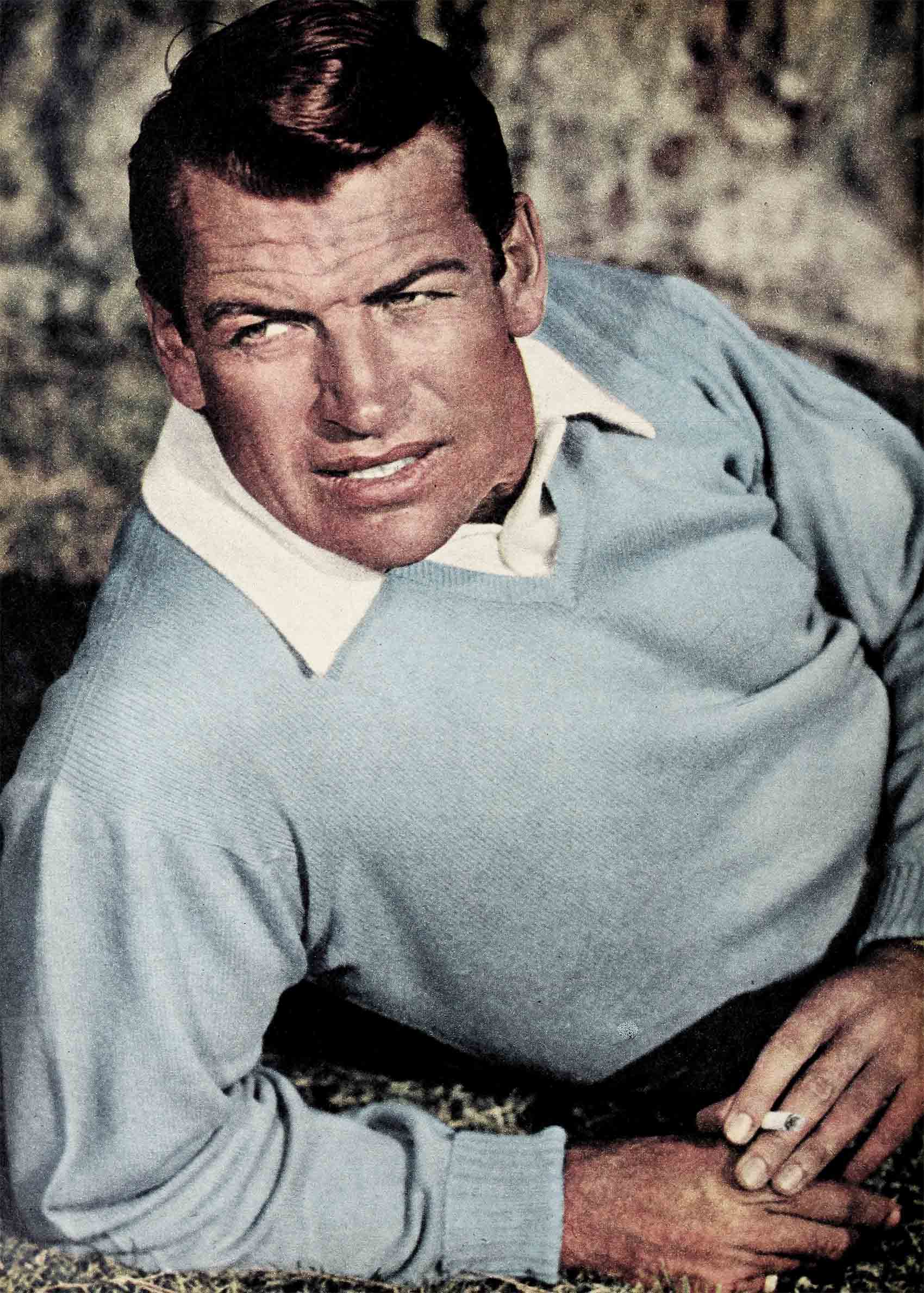

Dick’s efforts paid off well. In “Underwater!” he has his first real bid for stardom, his first big opportunity to show what he can really do. Fantastic as it seems—considering Dick’s six feet two of rugged masculinity, his thick brown hair, his deep blue eyes, superb speaking voice and strong rugged features—“Underwater!” is Dick’s twenty-first picture. Yet so crazy a place is Hollywood that nobody discovered him until he took off his shirt.

It was as the leading loin-clothed gladiator in “Demetrius and the Gladiators” that Dick made this important exposure of his talent and started a new trend in his career, one that accents his physical prowess. As a result, the mail immediately poured in on him and he got his first straight lead in “Wicked Woman.” “Wicked Woman” did no great shakes at the boxoffice but it wasn’t because of Dick. His talents were recognized and he went into “Gog,” then into the lead in “Khyber Patrol” with Dawn Addams. When Bob Mitchum decided not to go into “Underwater!” with Jane Russell, Dick was tapped for it. He got the male lead as Jane Russell’s husband, which he didn’t find hard to take.

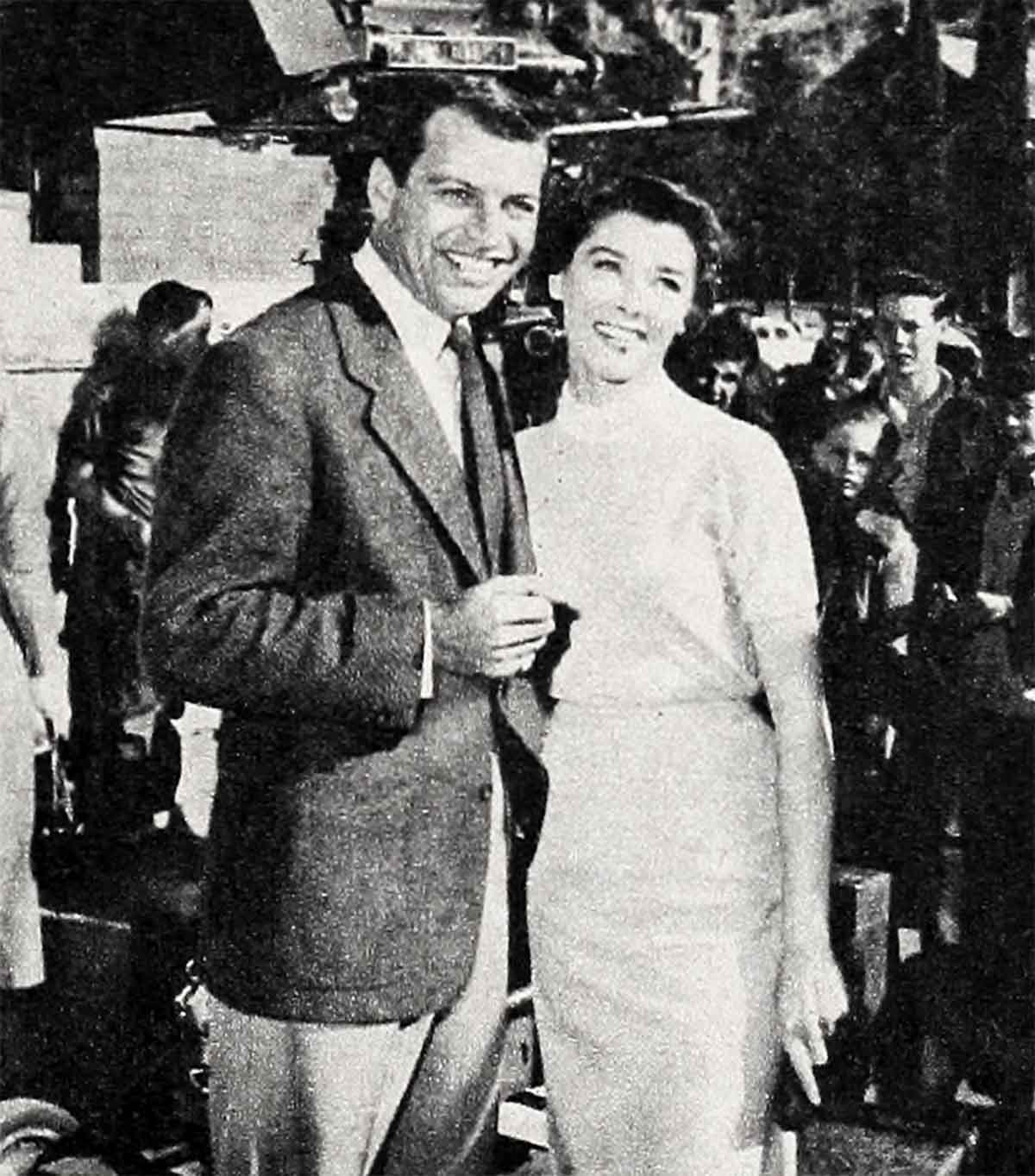

At the end of the first two weeks of shooting on “Underwater!” the whisper was already around Hollywood on him, and 20th Century-Fox got him on the dotted line, with plans that are super-CinemaScope collosal. Now all the carefully contrived machinery of Hollywood fame is being geared for him, the interviews, the photographs, the picture layouts, the trips here and there to meet fans and influence audiences. In this capacity, Dick should have no trouble; he’s been influencing peo- ple ever since he was born in San Francisco, July 29, 1921.

As a youngster Dick went to Jefferson Grammar School and St. Ignatius Prep in San Francisco. It was while attending Jefferson that he got his first theatrical role (“the traveling salesman from America in ‘The Windmills of Holland’ ”). He impressed his teacher, Dorothy Bailly, so very much that she encouraged Dick to pursue his newfound interest. In fact, today, Dick looks back on Miss Bailly “as the one who launched my career.”

Dick’s second big role was in an oratorical contest sponsored by the California Crusaders to promote American citizenship. He was seventeen and one of 15,000 contestants. With his distinctive speaking voice and poise, Dick won hands down (“I wasn’t impressed, I just thought that’s the way it would be”).

Thinking back on this today, Dick wishes, “If you were only smarter in your teens so you could send yourself a warning signal when things are won too easily. It’s a shame you don’t realize then when things are easy. Instead, you just sort of think that every miraculous thing that happens to you is merely your due.

“I remember thinking that I knew every last word on the subject of citizenship. I wasn’t a bit surprised when they announced I was better than fourteen thousand, nine hundred and ninety-nine other contestants. The Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court addressed us at the finals and I remember thinking, he’s pretty good, too. As a prize, I won a trip to Honolulu and elegantly (so I thought) consented to take my mother along. From that moment on, the ham really boiled in me.

“At St. Ignatius I started my drama studies, and at the time, in my humble opinion, I was as good as Edwin Booth. By the time I went to the University of San Francisco to continue my drama studies and major in English, I was my own Laurence Olivier. My whole life was bound up with the theatre. And it was not until 1942, when I graduated from college, that I did the first thing in fifteen years that didn’t involve the theatre. I enlisted in the Army—despite a strong inclination to believe I was heaven’s gift to the American drama. After doing a four-year bit, I was discharged.”

What Rich never points out is that he went into the Army a private, served in the Philippines and emerged a captain—and a judo expert. This is part of his modesty—an attitude that he has had to learn the hard way. Dick’s now modest about everything, like the fact that he has his M.A. in theatre history and dramatic literature, and there aren’t too many actors around Hollywood with such a sheepskin lining the wall; the fact that he’s taught speech at the University of San Francisco and is just as familiarly acquainted with Stendahl and Shakespeare as he is with Steinbeck and Shellabarger. About these things, Rich feels he has too much more to learn to worry about what he’s already mastered. Such feelings, he says, are the result of his experiences after the war.

“When I got out of the service, Solly Biano, Warners’ talent scout, saw me at Stanford where I was working on my master’s and acting, and he paged me. I thought this was merely very smart of Hollywood. After all, in college I had played Othello, Lennie in ‘Of Mice and Men,’ Buckingham in ‘Richard III,’ and many other roles. There was no place for me to go but straight to Hollywood.

“I came down from San Francisco with assurance and no worry about my screen test. When I arrived, Warners was in a layoff, this was back in ’forty-nine, and the test was canceled. But M-G-M was offered the opportunity to test me and they did.

“I gave out for M-G-M with a scene that would have stumped Spencer Tracy. Not that knowing this would have stopped me if anybody had pointed it out. I was Egan. Who was Tracy? The ham really boiled in me.

“Well, the results of the test were so good that M-G-M didn’t even bother to say they’d call me. They just said No. Later, with Solly’s influence, I got tested at U-I, than at 20th, finally at Warners. There was no doubt about my talent—all three studios said No.

“I’ll never in my whole life forget the disappointment, the letdown and bewilderment I felt. The first harsh shock was painful, but I had enough energy to feel that the studios could be wrong, I still had that much confidence. But as the weeks dragged by, I had to face the awful truth—for the first time in my life, it occurred to me that I might not be as good as I thought I was. It’s a tough blow to take. You kind of get used to considering yourself in one way; it’s difficult to think you might have been kidding yourself.

“Everything seemed to come to an end at once and I had nothing to do but go back home—which in the long run was the best thing I could have done. I went back and talked to my brother Willis, who is a Jesuit priest. Willis has been a big influence in my life and I’ve always admired and respected him. If he’d told me to quit acting, I think I would have done it. Instead, he told me to go back and do something about it. To study and prepare more. I came back to Hollywood to try again. I just couldn’t accept a No; I had to find out why.

“In time I was able to analyze my problem. In studying drama, one tries always to be aware of the author’s concept of the character, to interpret what kind of personality the author intended and from this create the personality through acting. Every part I played I tried to recreate the character as I believed the author intended. As a result, in all the screen tests, the Egan personality never came through—which is just what I thought I was supposed to do. Instead I just became part of the play’s props. I soon began to realize that motion pictures are a completely different medium and the actor in this medium has to project his own personality and play the role from his own personality, like John Wayne, Robert Mitchum and Cary Grant do. This was of enormous help.

“After returning to Hollywood, I took a small apartment. I didn’t know a soul. Not only was I unable to get to see a casting director, but I couldn’t even get an agent. I lived on checks from home, which was very humiliating. I suppose I was like thousands of other guys in Hollywood, but that didn’t make the taking any easier. I just sat there by the phone, afraid to go out for fear it might ring and I’d miss an opportunity. Weeks went by, and I’m not ashamed to admit that there were nights when for sheer loneliness and homesickness I sat by that phone and cried.

“Then Solly Biano, my original guardian angel, did call and without a test put me in ‘The Return of the Frontiersman.’ It was little more than a bit. I’m sure I wasn’t much good in it—but I got some- thing worth a fortune from that picture.

“Because I saw what it was to be a pro. I saw what it was to walk in, cold, on a set, and to be ready: to know your lines, to project your personality. And I saw that integrity was the integrity of acting and of your own personality.

“That was the beginning. I gradually got into other things. They were all quickies and I rarely played anything that held the camera more than a few minutes—but I was learning.

“And gradually people were wonderful to me. Crawford helped me tremendously that second picture. A good agent finally agreed to handle me. And three years to the day from the time M-G-M turned me down, they sent me to Europe for ‘Devil Makes Three.’ The trip was great.

“When the day came that my mother and father agreed to come down here and keep house for me—the wonderful reverse of my taking those checks from them—and then when I secured my 20th contract, as the result of this picture, ‘Underwater!’, well . . .” He spread his big hands and grinned.

There’s nothing lacking in Dick’s wonderful life but a girl.

Not too many people know there was a girl very important in Rich’s life since he’s been in Hollywood—but it couldn’t work out, he being the devout Catholic he is, and she being divorced.

And currently, though you’d never get him to mention it, it makes him uncomfortable to be in the Hollywood “unattached, eligible male” position he is, so that his telephone rings day and night. He’d like to do his own pursuing.

Besides, with his parents anticipating his every wish for comfort, he has as much domestic life as he likes. And what he is in love with, for the time being anyhow, is his career. He never swam in a serious way until he was cast for “Underwater!” whereupon he took lessons for two hours a day for two months. It was the same with riding. “Khyber Patrol” made that necessary, so he rode five hours a day for a month, getting ready.

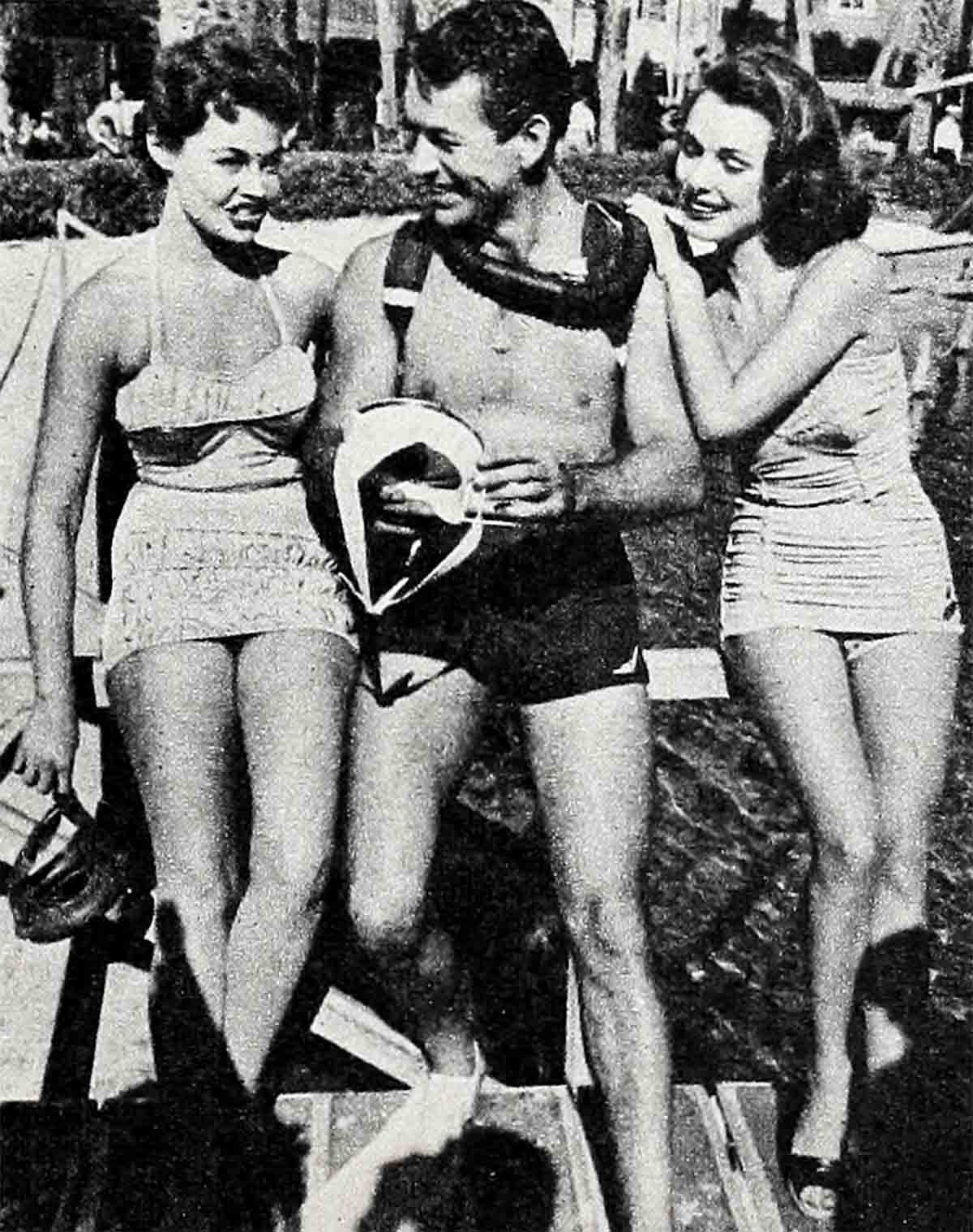

Nevertheless, he gets quite a gleam in his eye around small, blond girls. Or tall, brunette ones. Or just girls.

And as for the girls around him—brother!

THE END

—BY RUTH WATERBURY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1955