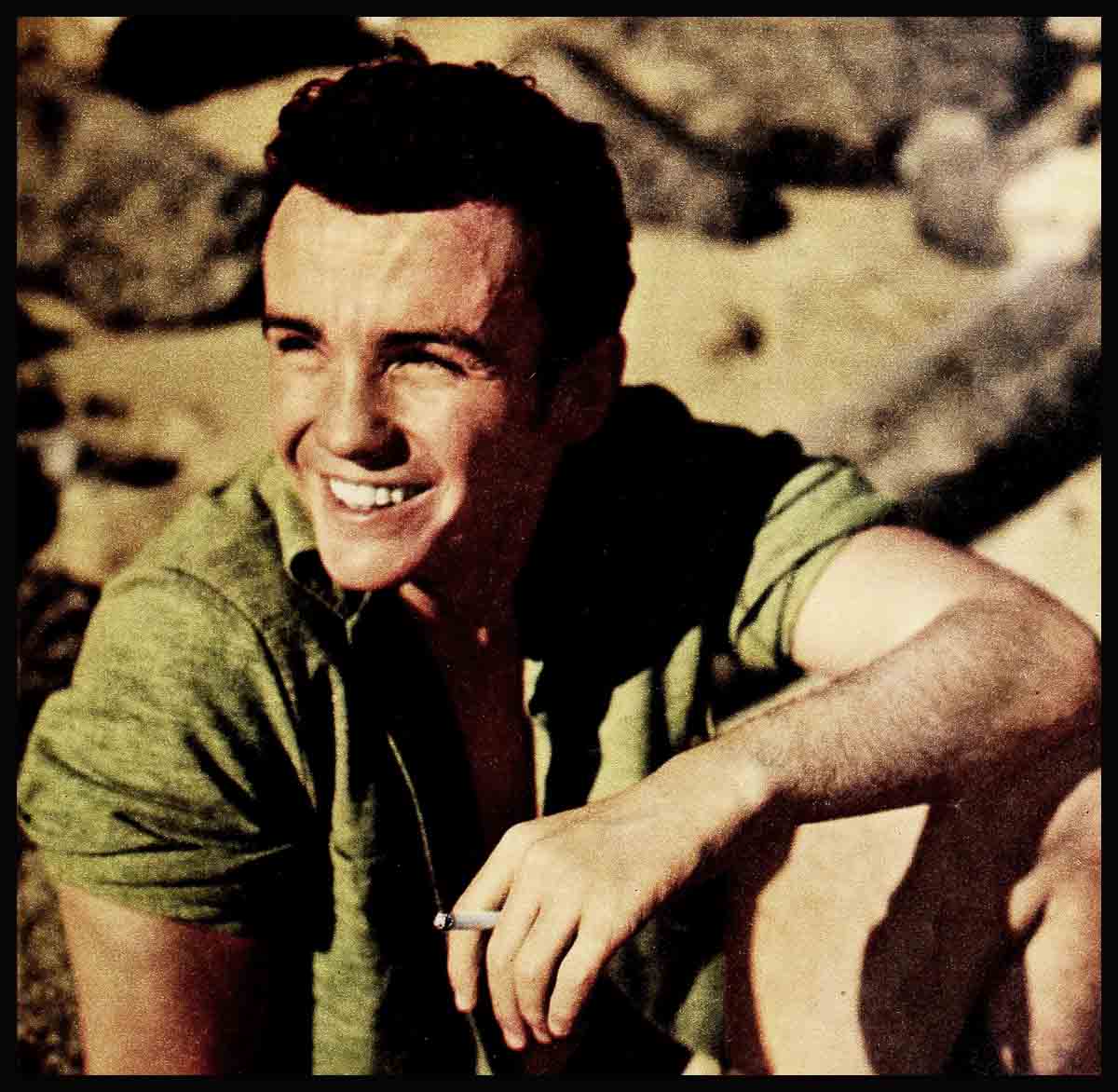

The Two Loves Of Ben Cooper

John Wayne, except for a penchant for dark-haired women, perhaps, is not known to be easily impressed by anyone. But he went to a movie the other day to catch the performance of a new, young actor named Ben Cooper (who, incidentally, is already showing a penchant for both dark-haired and light-haired girls). Wayne was doing a service for his press agent, Bev Barnett, who represents such other veterans as Dick Powell, Gene Autry and Johnny Weissmuller. Barnett wanted to know if Wayne thought Bev had himself some fresh blood in Ben, his latest client.

Wayne came to the point. “You’ve got yourself new blood, all right,” he told Barnett. “You’ve got yourself a star.”

When you remember that Wayne is a tall, 200-pound westerner who prefers the company of big, mature men like himself in both his work and his play, you wonder what he found to like in a small, blue-eyed Irishman from New York who weighs about 150 pounds and stands only five feet, seven inches high. The real answer probably is that Ben Cooper is small in size only. In ambition and accomplishment he is beginning to stack up around the casting offices as a combination of Spencer Tracy, Kirk Douglas and Gary Cooper. Ben, in other words, can act, talk and ride. He was only eight years old when he made his theatrical debut before a Broadway audience. His roles in radio plays alone total some 3,200 appearances. And just as a little bonus in talent, he handles a horse and a gun like a hero out of a Zane Grey novel—something he could do before he ever left New York.

Born in Hartford, Connecticut, and raised not forty-five minutes from Broadway in Beechurst, Long Island, Ben, as a sort of relaxation from soap opera work, bought a pony, named him Gypsy, and rode daily near his home in Queens.

In his wallet he carries two pictures. One is of a super-curved blonde named Lee Sharon who headlines nightclub shows in such seaports as New York, Miami and Tokyo, doing dances which Ben describes as modern but which more professional critics seem to think are strip routines. The other picture shows Gypsy, mounted by a headless horseman. The photo was too large to fit into the wallet and something had to be sacrificed—either part of Gypsy or part of Ben. So Ben tore off his own head.

As he explains, “Well, I know what I look like. After all, it was Gypsy I wanted to remember, And Lee, of course.”

He didn’t mean that he has lost his head over Lee as well, but that is what most of his friends think. He has gone out with Anna Maria Alberghetti, whom he admittedly likes; he gets really animated when he talks about Pat Crowley, with whom he used to go to high school in New York; and he’ll slick himself up sharp and shiny for a date with Lori Nelson. But the plain fact, say those in whom he confides such matters, is that he is crazy about Lee Sharon. She, dancing lately at the Latin Quarter in New York, is said to have flashed into Ben’s life last November. She was the date of a friend of Ben’s, who dropped in to see him one afternoon and was thereafter minus one girl.

They dated around town for about six weeks while Ben was working in The Rose Tattoo, in which he has co-starring billing with Burt Lancaster, Anna Magnani and Marisa Pavan. Then Lee had to go to New York. While Ben didn’t write home about Lee, word reached his folks and his father wrote to him. Father also telephoned. If, as reported, the affair is still on, so are the family discussions.

“Oh, it’s just a case of Lee’s being the first girl Ben has ever known well,” explained Barnett. “You know what that can do to a young fellow.”

“Yes!” chimed in Ben, as if happily remembering.

Ben is very proud of his father, Ben Cooper, Sr., a mechanical designing engineer who graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is the brains behind such devices as practical truck winches, tractor hoisting devices and the fearsome looking cranes on aircraft carriers that clear the landing deck of plane smashups by hurling them into the sea. Brian Donlevy once made the mistake of asking Ben about his father and was still hearing about him a half hour later. Ben’s mother, Mrs. Berna Cooper, is closely identified with his first years in show business, practically managing as well as mothering him through that period. And his older sister Bunny, now modeling in New York, has received a number of offers to come to Hollywood and probably will be testing for a picture by the time this story is in print. So Ben doesn’t want any trouble with his family about Lee. But he doesn’t want any trouble with Lee about anything.

When Ben’s birth was being awaited by his mother back in 1933, a year still depression-thin, she got quite a bit of sympathy from her neighbors. “What a shame!” commented one of them. “Here you are expecting another child and things still so bad off. Just the luck of the Irish to be taking on a new burden now!”

“Oh, him!” retorted Mrs. Cooper, who had already borne a daughter and was sure the second baby would be a boy. “Oh, he’ll be earning his own way before he’s ten!”

It was a wild guess but a good one. At nine Ben was making $50 a week playing, Harlan, the youngest redheaded son in Life With Father on Broadway, starring Howard Lindsay as the father. It was a play he was to stay with three years. No Cooper had ever before been on the stage. A friend of the family had heard! that the producers were looking for an eight-year-old and while watching Ben romp around she got the idea that he would make a good actor. “You know, he doesn’t pretend he’s a cowboy or a policeman like the other little boys,” she told his mother. “He seems to be pretending that he’s pretending—just like I saw John Barrymore do once!”

The family had moved to Beechurst from Hartford by this time. Mrs. Cooper took Ben down to the old Empire Theatre, where the play was running, to join fifty other waiting mother-and-son pairs.

“How many plays has your little boy been in?” one of these ladies asked Mrs. Cooper.

“None,” replied Ben’s mother.

“Oh!” retorted the other patronizingly, while a few dozen of the other mothers! gazed at her superciliously. Mrs. Cooper gripped Ben’s hand and settled herself more solidly in her seat. Tired of waiting, she had been ready to leave. Now she was determined to stick it out. One week later, after a series of elimination tests, Ben had the job. Given a copy of the play and told to memorize about a page and a half of it for his audition, Ben, in four days, learned the complete role of Harlan, running fifty pages. That did it.

It was on the fifth night of his career, as an actor that he won special commendation from Lindsay. A prop man had forgotten to leave a copy of the catechisms on the bookshelf in one scene, and it became necessary for Father Lindsay to ad lib a request to one of his other sons, Whitney, to go out and get the book. Alone now on the stage with Ben, with whom he would have to ad lib further to cover the situation until Whitney returned, Lindsay said, “Well, Harlan, what would you like to have me read to you?”

The moment the words were out of his mouth Lindsay was sorry. He was certain that an eight-year-old boy like Harlan could only reply to such a question by naming some comic book character like Superman—an awful boner, since the time of the play was at the turn of the century.

Instead, and for reasons which he cannot explain even to this day, since he did read many comic books then, Ben named a beautifully appropriate book, Gulliver’s Travels. Lindsay practically got tears in his eyes in his relief and when Ben walked off the stage at the end of the scene his “mother,” Dorothy Stickney, who was Lindsay’s wife both in real life and in the play, gathered him into her arms for a rewarding hug. “A pro! A real pro!” Lindsay chortled when Ben came off.

With his first $50 Ben fulfilled an ambition to buy his mother “a beautiful new dress” and to give his father “a whole dollar.” He then wanted to enter a formal objection to the deduction of fifty cents from his weekly wages for Old Age Benefits (as explained by his father), claiming that by the time he got to be sixty-five years old the Government would never be able to remember whom they owed the money to.

His folks recall that Ben “aged” very fast after he became an actor. One evening his father was driving him to the theatre when they passed a car in which sat a four-year-old boy with beautiful curls.

“That’s just the way your hair was when you were his age,” Ben’s father remarked.

Ben studied the boy, and after some thought asked, “Dad, how does it feel to have me all grown up?”

Ben wasn’t nine years old yet, but his father didn’t point that out. He just took a quick look at his son, saw that he was serious, and said, “Oh, it’s a deep comfort, a deep comfort.”

A year after Ben joined the show he was stricken with pleurisy and had to miss some performances. On the first night that he knew he wouldn’t be able to go to the theatre he begged for an alarm clock. Timing himself according to the routine of the show he began playing his part in bed. He would have presented the entire play had the doctor not rung down the curtain with the aid of a sedative.

Ben attended school regularly all through the run of Life With Father at St. Luke’s Parochial School in Whitestone, Long Island. Later, as he got into radio and television work, he went to Lodge High School (a private school in New York) and Columbia University. He finished his sophomore year at Columbia but never got to be a junior, because Hollywood was making noises like gold in the bank by this time. Hollywood knew what it was doing; Ben had accumulated a background of experience probably never before equalled by a youngster of his age.

He was in the cast of thirty-two soap operas before he was twenty. Among other characters he played were Dickie in Portia Faces Life, Brad in The Second Mrs. Burton, Ernest in Joyce Jordan, Billy in Big Sister, Mack in Young Widow Brown and Les Wentworth in Tennessee Jed. This didn’t take all his time, by any means. Over the years he appeared in such top radio and television presentations as Suspense, Kraft Theatre, Cavalcade Of America, Inner Sanctum, Studio One and Armstrong Circle Theatre. And long before he came to Hollywood he had supported many Hollywood stars in New York broadcasts, including Helen Hayes, Joseph Cotten, Robert Mitchum, Gene Tierney, Claudette Colbert, Van Heflin and Basil Rathbone. He became known as a player of wide versatility and many dialects; he has portrayed Englishmen, Frenchmen, Germans, Spaniards, Mexicans and even Japanese.

Naturally, when he had to write a paper at Columbia, and chose “Soap Operas” for his subject, he was able to write it without doing any research. He had also learned a little bit about the economics of his profession by this time and it isn’t likely that anyone in Hollywood will slip a bad contract or deal over on him. Ben was only nineteen when he was elected a delegate to the merger session of the radio and television actors’ unions into the one organization, AFTRA, The American Federation of Television and Radio Actors.

Ben failed to make good on his first trip to Hollywood. This was in May, 1952, when a New York Warner Brothers scout signed him to test for a role in Retreat, Hell! The part went to Russ Tamblyn instead and Ben wasted no time brooding. Even while waiting for his plane back to New York he telephoned several producers there, got himself booked back into several radio shows and was ready to step into an Armstrong Circle Theatre play, an hour after he landed at La Guardia.

In the meantime, head men at Republic were shown the Warner Brothers test and decided Ben would be a good bet for a role in a war film, Thunderbirds, which they were planning. It was while he was working in this picture that Republic’s president, Herbert Yates, saw Ben galloping a horse. In his time, Mr. Yates has had such western notables as Autry, Roy Rogers, Tex Ritter and Rocky Lane riding the celluloid range for him. He decided right then to corral Ben for a long run at the studio. Since then Ben has appeared in ten pictures, his best roles being that of Jesse James in The Woman They Almost Lynched, Turkey, the young desperado who is lynched in Johnny Guitar and Sailor Jack in The Rose Tattoo.

Just getting the role of Sailor Jack was harder than playing it, Ben thinks. Some three hundred young actors were after it. All were interviewed, more than a hundred gave readings, and about a dozen were tested. The day Ben’s test was screened Wallis and the director, Danny Mann, announced that the search was over.

Ben has a small apartment in the San Fernando Valley almost across the street from his studio. He does his own cooking, and isn’t as good at it as he claims to be, according to his friends. He has been plunking away at a guitar for the last year without becoming a Les Paul and he spends the rest of his spare time riding and practicing his draw with a six-shooter. He says he has timed himself and has it down to a fifth of a second.

“Is that fast?” Joan Crawford asked him recently, when he was demonstrating for her benefit. Ben gave her another gun and showed how he could pull his gun, cock the hammer and shoot it while she was still just pressing the trigger of hers.

“Well!” she exclaimed. “I should think you’d have to be born nervous to move that quick!”

Ben, a cool, assured performer when he is working, is apparently far from being a nervous man. But he does give this impression offstage because he is naturally spry, flit-quick with word and gesture, and very intense. He is also apparently one of those wiry Irishmen who are indestructible. During the filming of Johnny Guitar he fell flat on his back from a ten-foot-high wagon perch when his horse decided suddenly not to be where he should be. For two minutes thereafter Ben was unconscious while the director, Nick Ray, and the other cast members, Scott Brady, Ernest Borgnine and Royal Dana, worked over him. For the next three minutes, after he had. opened his eyes, he was paralyzed, unable to move a muscle in his body, but five minutes later he was again jumping from the perch, this time landing on his horse as planned.

Ben likes Hollywood. He is young enough to be looking for laughs most of the time and he has friends on every level. One of his pals is the well-known part-time actor and part-time parking attendant at Ciro’s, Jimmy Murphy. Ben stops by to see him often, and is therefore probably the only actor in Hollywood who goes to Ciro’s usually to spend his time outside the place. Not that he doesn’t occasionally attend as a guest.

When the popular Sammy Davis had his premiére at Ciro’s following the tragic car accident which cost him an eye, Ben took Anna Maria Alberghetti. Practically every big name in Hollywood also attended, and after the show they all trooped out to vie with each other in having their Cadillacs brought up to them. But the first car was not a Caddie. It was a 1953, newly-washed, aquamarine Mercury convertible, registered to one Benjamin Cooper. Despite the “long green” most of the big stars were waving in their hands, Jimmy Murphy was already seated in Ben’s car waiting for his pal to appear. The moment Ben lifted a little finger Jimmy scorched up with the Merc. After Ben and Anna Maria climbed in, the stars watched open-mouthed as Ben very solemnly handed Jimmy a dime tip.

“I don’t get it,” said a puzzled star who was ready to tip fifty times this amount. “Maybe I am losing touch with the people!”

Incidentally, after John Wayne told press agent Barnett that he thought Ben was a star, he also announced that he wants to make a picture with Ben. So does Dick Powell. And practically every studio in town is looking around for a story in which Ben would fit.

So Barnett is quite happy about his new client except for one habit of Ben’s. Ben not only loves to ride a horse, he loves to talk about it; and every time he talks about it he insists upon demonstrating that he has ridden himself bow-legged.

“He isn’t bow-legged!” declares Barnett, who knows that a straight-legged star will go much further and last much longer in the business. “He pretty nearly breaks his legs straining them backward to make them look bowed, and as though he belongs on a saddle and nowhere else.”

“I am too bow-legged!” Ben came back heatedly one night.

“G’wan!” retorted Barnett. “You’re just trying to be true to your old horse, Gypsy!”

That stopped Ben. So that night he went home and wrote a long letter to Lee Sharon, asking her, among other things, to go see Gypsy for him.

THE END

—BY LOUIS POLLOCK

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1955