That Nice Young Family Next Door—Jack Lemmon & Cynthia Stone

If a household loaded to the eaves with talent is within the realm of normalcy, the Jack Lemmon residence must be said to be absolutely normal. The house itself speaks for the people who belong there: airy and sunny, with just enough formality to reflect the tastes of a man from down east and a girl from the midwest. Nobody walking in cold would guess that a movie star lived here.

In fact, you’d be hard pressed to find anyone who thinks of Jack in those terms. “That nice young family,” is what the neighbors call Jack and Cindy and Christopher Lemmon—and it isn’t because they don’t know that Jack works in pictures. When he leaves for the studio of a morning, Jack looks just like a prosperous young banker—or the doughnut salesman he might have been if he had entered the family business.

Between pictures the neighbors see him in slacks and what Cindy calls “the worst looking shirt I ever saw,” puttering in the garden or his workshop, practicing a chip shot with one of his short irons. They meet the Lemmons in a nearby supermart where Jack is just another guy hefting lettuce instead of lotus blossoms, carrying a carton of Cokes instead of a case of champagne, patiently waiting his turn behind you at the checking counter.

Even people who are impressed by stars find it difficult to think of Jack as one. As Cindy tells it: “This girl I went to school with came down from Santa Barbara with her husband—she’s a close friend of mine—and we gave them the full treatment. Ciro’s, the Mocambo, everything. She was terribly disappointed, though, because there didn’t seem to be any movie stars out that night. After she remarked a few times that here she was in Hollywood and not a single star in sight, I leaned over and said, ‘Dear, you’re with one.’

“She recovered fast enough afterward, but when she asked, ‘I am?’ she was only half-kidding.”

Despite his everyday manner, Jack Lemmon is a major talent. He can sing, dance, play a straight role, pie-in-the-face or hearts and flowers flawlessly. And has done so on stage, screen, television and radio. Negotiations are underway for him to direct a major TV presentation next season. In New York Jack produced three TV series co-starring with his bride-to-be.

“Those were the days!” he says as if they were fifty years past instead of five. “We had one camera and, most of the time, two characters: Cindy and me. That was the show. If there was too much action, we’d lose the camera—and maybe you don’t think it’s hard to sustain pace with just a couple of people talking for ten or twelve minutes. But we did it and we must have been all right; we made a lot of money out of it.”

It’s typical of Jack that though there were some times in New York he had to scratch for an existence, he couldn’t see asking the family for help. “No, I did borrow five or ten dollars a couple of times,” he admits, “but I paid it all back—including the original investment.” (Lemmon, Sr. staked his Harvard-bred, stagestruck son to $300.)

While making the professional rounds in Manhattan, he met a fine young actress named Cynthia Stone. She is tall, too thin, a true blonde with clear blue eyes, clear tanned skin and impossibly perfect white teeth. When she first encountered Jack Lemmon, she was engaged to a Harvard law student.

“I did not break up their romance,” Jack insists blandly. “Maybe I had an advantage because Cindy was interested in the theatre and I was the only actor she knew.” He grins. “I just gave it a little nudge.”

Cindy’s version, related when Jack is elsewhere, does less fiddling with the facts. “Well, we were planning to be married, even though the engagement wasn’t official yet. But, from the first time I met Jack, I knew it wouldn’t be right for me to marry anyone else when he attracted me so much. Not that I let him know it at the start, since he didn’t even give me a tumble—but I had to do some quick revising of my plans.”

Sporting fellow that he is, Jack has enormous admiration for his erstwhile rival, chiefly because the guy had imagination. The night that he and Cynthia opened in an off-Broadway but nonetheless legitimate production, Jack walked his leading lady home. And in front of her apartment building they found a titillated crowd gathered about a gentleman who wore a sandwich board proclaiming in large black print the beauty and superb talents of one Cynthia Stone. He had been hired by the law student.

Cindy, who had hoped that her serious dramatic aspirations were impressing the handsome actor with the thick, dark eyelashes and the impudent grin, dissolved into tears of embarrassment. Jack howled.

“Not only that,” he’ll tell you admiringly, “he was going to hire a sky writer, too, except that Cindy said she’d never speak to him again if he did.”

Shortly thereafter Jack gave Cynthia that earth-moving tumble for which she yearned. They did exactly what you would expect of two well-brought-up youngsters; they bided their time until they could go back to her home in Peoria, Illinois, to be married on May 7, 1950. It was like them to have a proper wedding, chapter and verse, rather than a hasty civil ceremony performed by a justice of the peace. They still go back to Peoria to celebrate Christmas every year. Nice and normal. Besides they miss the snow.

“I remember,” Cynthia says nostalgically. “You’re walking at night in New York either because you can’t find a cab or can’t afford one and it’s winter, so cold that you almost can’t stand it. There isn’t anything more wonderful than turning in at the old brownstone house where you live, running upstairs, and putting a match to the logs in the fireplace. Or driving to Long Island or Connecticut on a clear, nippy day when the colors of the leaves make your throat ache. Or, after a bad winter, waking up on one of those spring days that only happen to Manhattan—crisp, clean, brilliant and, well, just exciting. It can’t be explained; it’s something you have to feel.”

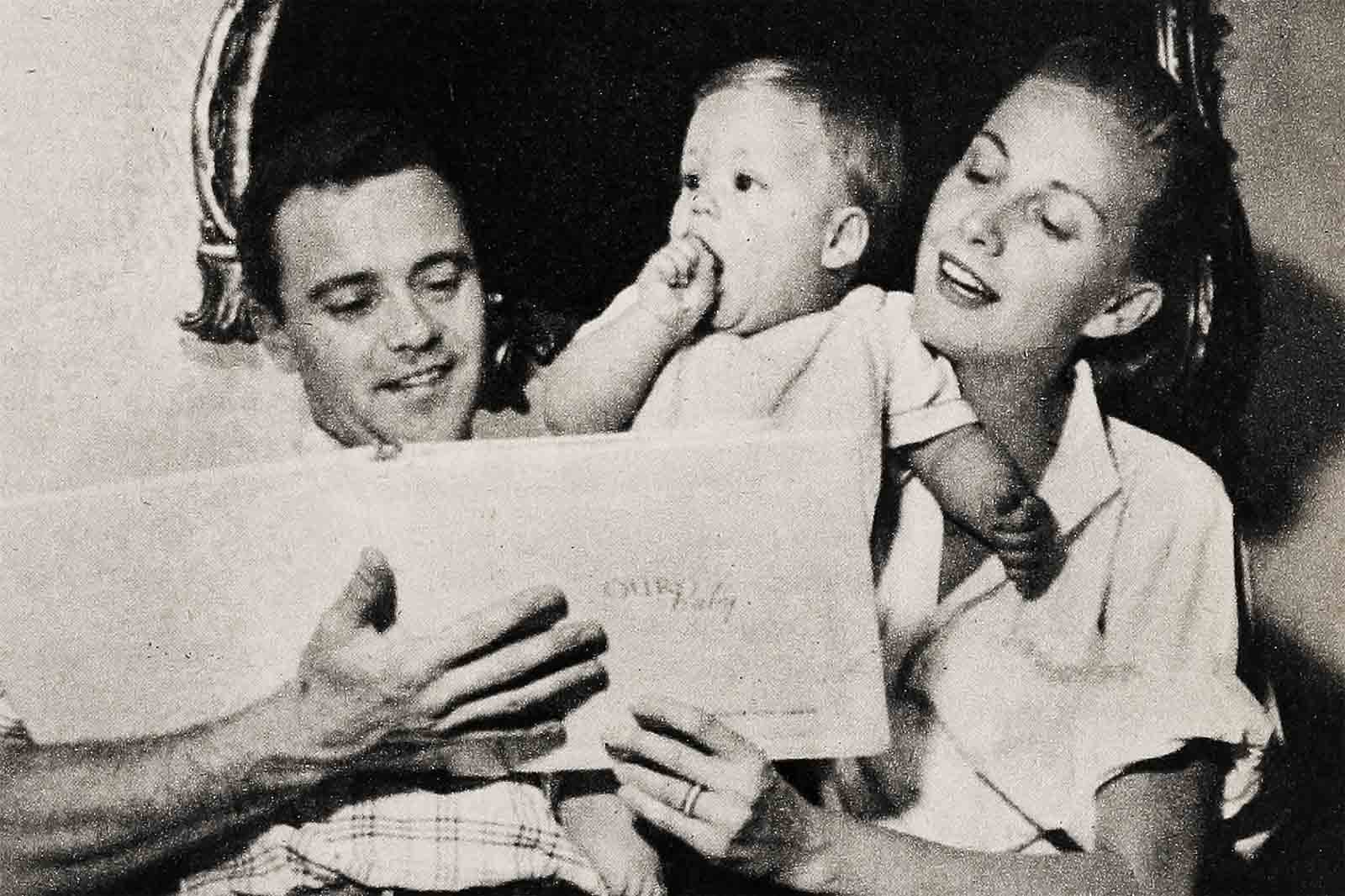

But the Lemmons aren’t about to swap the warmth and friendliness of California for nostalgia. This is home now. “We love it and, besides, it’s perfect for Chris. Where else could a baby be outside practically all day?”

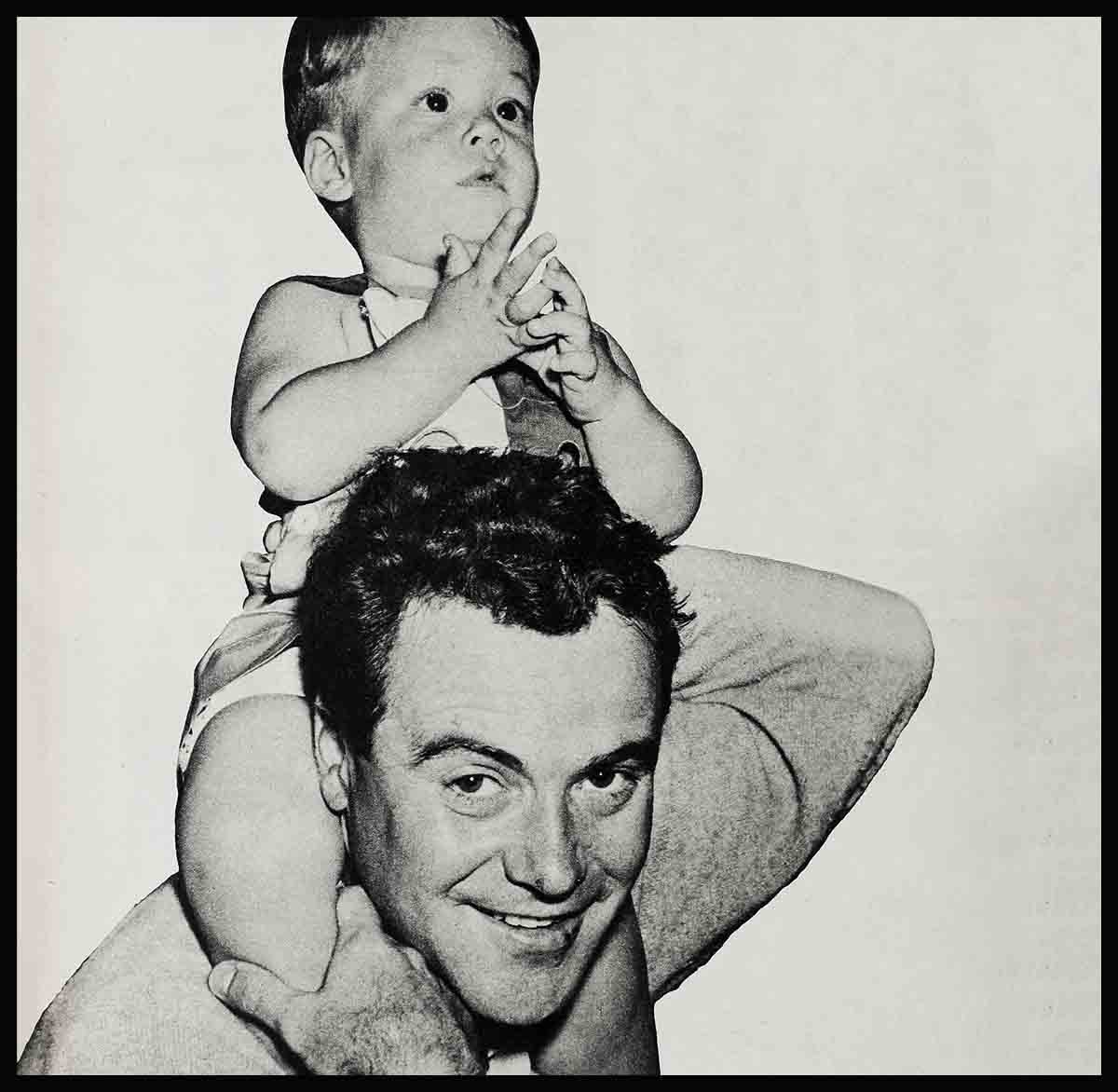

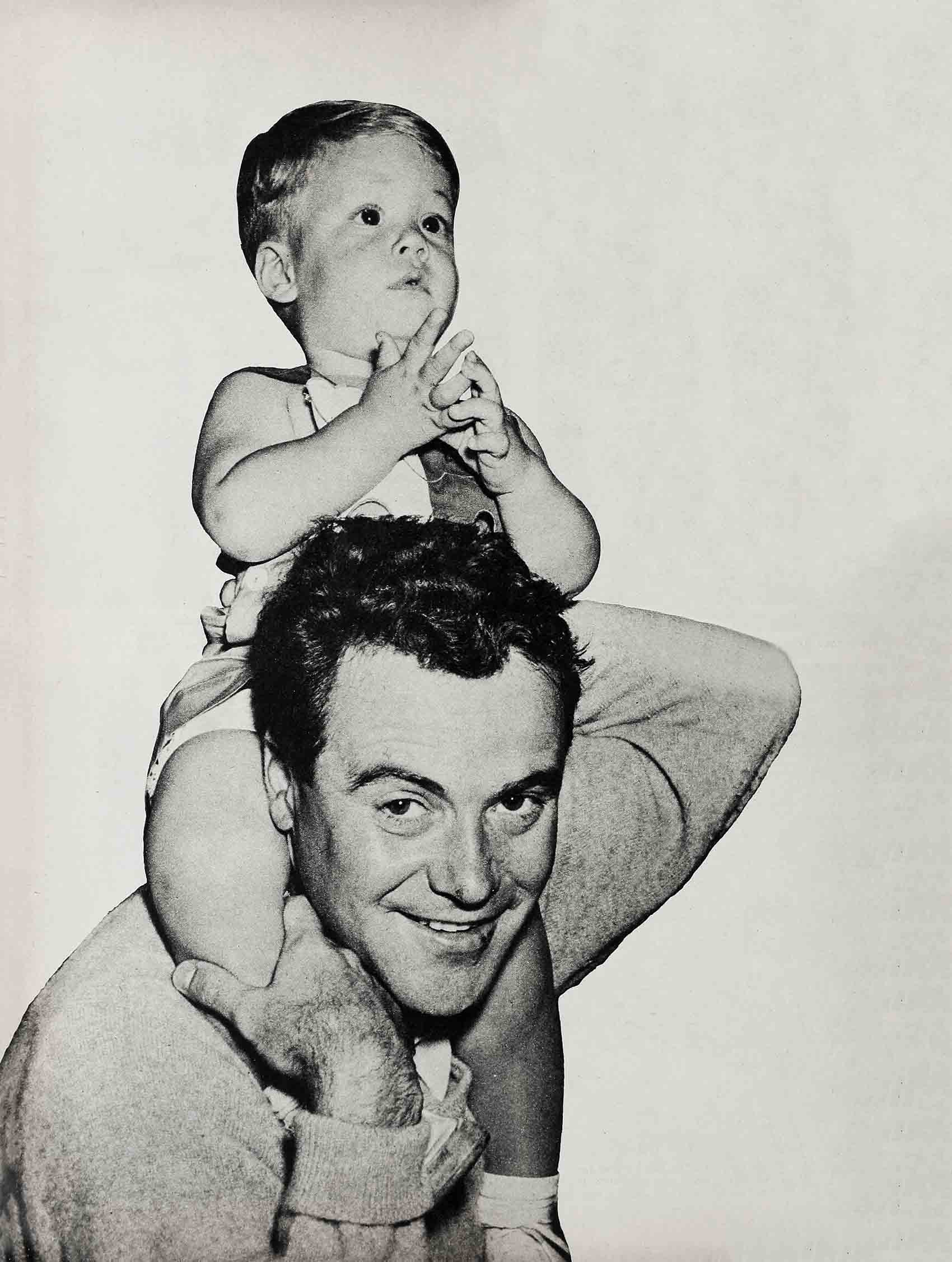

Master Christopher grows so rapidly that Jack cautions Cindy. “Don’t antagonize him, honey. He might turn on us.” He wouldn’t, of course, being a nice little guy who retires at seven in the evening and doesn’t assert himself again until seven the next morning. And has followed this highly desirable schedule since he was six months old. “We didn’t do it,” his parents concede. “When he came home from the hospital, he had a nurse who allowed no one in Christopher’s room after he went to bed. It seemed severe at the time, but she was the best thing that ever happened to us. We, being new parents, would have heard him stir and leapt up saying, ‘He’s awake! Get him up, change him, feed him, do something!’ Since he was trained from birth not to expect all that attention, he entertains himself. If he wakes up during the night, he sings, laughs, talks to himself, plays with his toes until he falls asleep again. It’s as simple as that.”

The routine of the Lemmons’ daily life revolves pretty much around Chris, as could be expected. Most important of all, the family has breakfast together every morning—a big one, too. Jack eats because he works so hard during a day’s shooting. Cindy eats like a trencherman because she would otherwise disappear into thin air. But Chris is privileged to throw his food on the floor at such an early hour because it’s his only chance to be with his father. He has retired for the night by the time Jack comes home from the studio, so breakfast is a big deal.

Now that Chris is a year and a half old, Cindy plans to resume her acting career but says, “I’ll make my appointments and read for parts in the morning whenever it’s possible; I want to be home by two or two-thirty if I can. That’s when Chris is getting up from his nap. I like to have those hours with him, and I try to give Impi every afternoon off because she’s so wonderful about the rest of the time.”

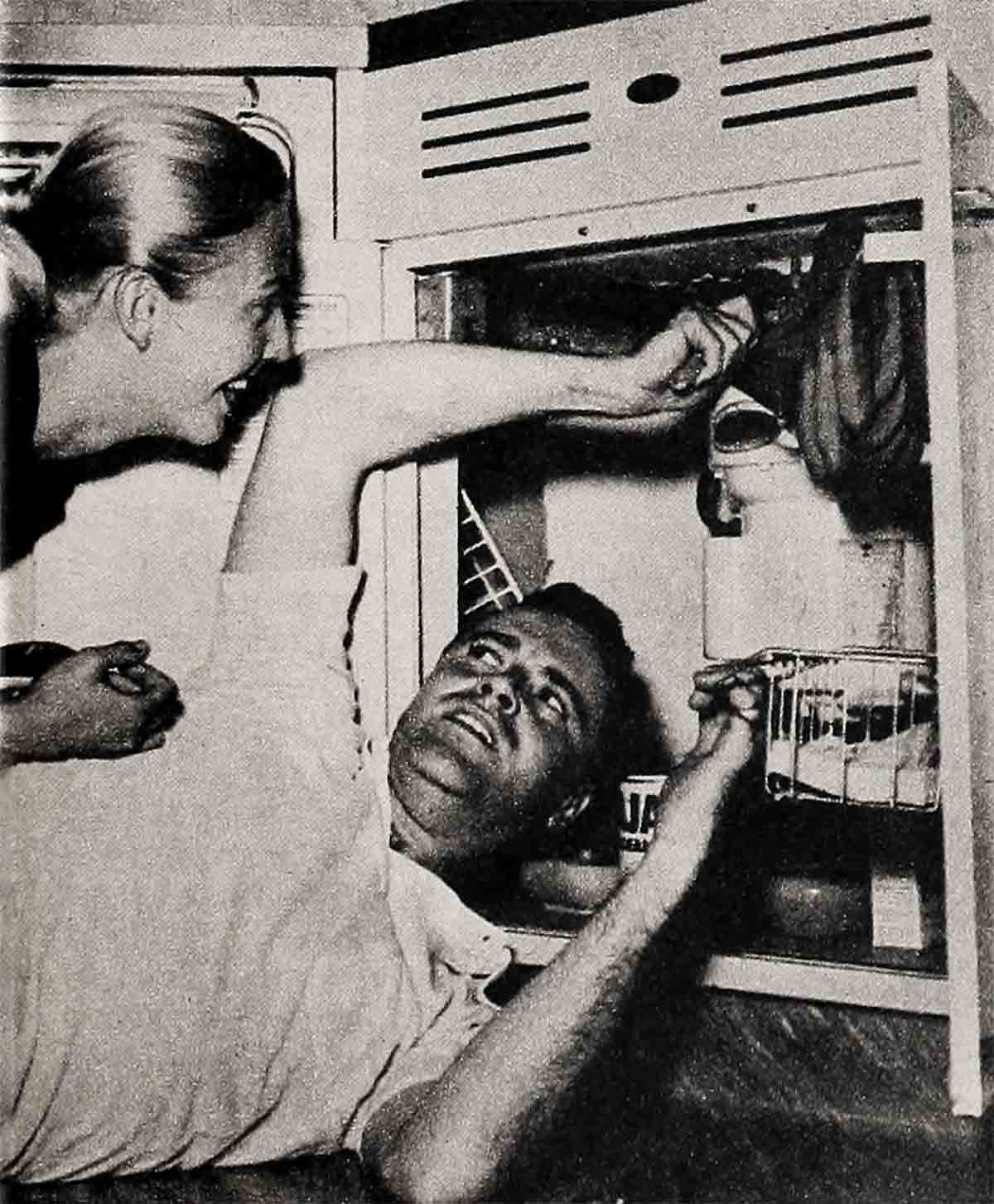

Impi is the fourth talent in the Lemmon household, and you’d meet a shotgun head on if you tried to lure her away. “She’s fantastic,” Jack said recently. “Nobody ever tells her to do anything and nobody can figure out when she sleeps. If you get up at six o’clock in the morning, you find the kitchen stove in sections on the floor: Impi’s cleaning it. If you get up for a drink of water at midnight, Impi is doing something to the silver. As for Chris, he loves her so much that we might as well not be around.”

Like most geniuses, Impi is not without foibles. She runs like a deer at the sight of strangers and has an aversion to telephones that borders on a compulsion. Jack is making headway in overcoming this latter bit—but not very much. A few weeks ago, when the phone rang and Impi pretended that this hateful thing had never happened, Jack remained seated, asking gently, “Impi, would you answer the phone, please?”

Her dark, almond eyes were momentarily imploring, then Impi drew a deep breath and picked up the instrument. “Lemmon residence. Please call back later,” she said, hanging up before he could stop her.

She’s scrupulous about their other needs. Jack is still a little keyed-up when he gets home at night, and it’s Cindy’s custom to relax him with a leisurely cocktail and an hour or so of civilized conversation before they dine. This means that they will not sit down to dinner until eight-thirty or nine, but almost as often as Cindy says she will serve them herself, Impi is there. She’d rather do it herself.

On such an evening the Lemmons watch TV for a while after dinner, always with one eye on the clock if Jack has an early studio call. Even when he isn’t working, they aren’t much for living it up in the Hollywood sense. They like to go to the neighborhood movies; they enjoy having small groups of friends over for one of Jack’s barbeque specialties or Cindy’s spaghetti, after which, believe it or not, they practice the lost art of conversation.

Cindy has been trying to teach her boy to play bridge, but one of them is hopeless. “I know he’d be a sensational player because he has such natural card sense,” she says. “In New York we used to play canasta with another couple every Saturday night because we were too poor to go out anywhere, and Jack was terrific at that. But bridge is so hard to explain. ‘Yes, dear, I know you did that last hand and it was right, but you shouldn’t have done it this hand.’ He’s perfectly reasonable; he just asks why not, and I’m lost.”

When they really have some free time, like a week, Cindy and Jack slip into the station wagon and take off with a minimum of fuss. Last time they went up into the High Sierras on a fishing trip, leaving Chris in the capable custody of Impi.

On the afternoon before, Jack came ambling through the house to find Cindy sitting on the study floor in a pair of crazy pants, surrounded by oddments of one kind or another. “Hi,” she greeted him. “I have news for you, sweetie. We aren’t having guests for dinner, after all.”

“Oh? Why not?”

“I called and told them not to come.”

“But, honey,” Jack said mildly, “You’ve already made all that spaghetti. Why won’t you let them come?”

“Well, you said you wanted to get an early start in the morning, and there’s all this to sort out,” Cindy gestured at the litter of boots, fishing gear and whatnot.

“Oh, sure. But we can go to the moom pitchers after dinner, can’t we?” Reassured on that score, he went about his business. If Cindy wanted to invite people for dinner, that was swell. If she wanted to disinvite them afterward, that was perfectly okay, too. Jack’s a happy man not given to worrying about women and their whims of iron.

But about that trip his eyes fairly sparkle with enthusiasm. “Man, if this isn’t it! See, you make arrangements with this packing company; you bring your own groceries and equipment, then they supply you with all the essential things you left at home. They put you on horses, load your stuff on a couple of mules and take you up to some spot that’s absolutely inaccessible any other way. After they pack you in, they leave, guides and animals. You’re on your own until whatever date you told them to come back for you. We had five days there.”

“You mean you can’t get back and there’s no means of communication?” asked the studio representative to whom Jack was relating his tale of adventure.

“Nope.”

“But suppose a snake bit you?”

Jack thought it over. “Perfectly all right,” he said, “they’d come up after my remains four days later.”

Happily, they didn’t encounter any snakes. “But I got claustrophobia,” Cindy admitted in an unusually small voice.

“Top that one if you can,” invited Jack, shaking his head. “We’re so high up in the mountains that there isn’t a building for miles around, and my wife gets claustrophobia!”

Cindy came to grief because of an Alaskan pup tent, in which there is barely room to sleep two people. Since she is quite tall and Jack is a lot of man, they were really wedged in. “Everything seemed all right until I turned over,” she said. “Then there was the tent against my nose and right over my head, the ground underneath me, and Jack like a rock at my back. I was suddenly terrified; I felt that I couldn’t breathe, couldn’t move, that I’d die if I didn’t get out.”

Feverishly she clawed at the small opening of the tent, and by the time she did find it, she was so badly panicked that getting her head and shoulders out wasn’t enough for her. She had to be free of that tent.

She stood in the open a long moment, shivering, sweating, panting, before the sleepy head of the man she had promised to love, honor and cherish emerged from the tent and his sleepy voice asked what was up.

“When she told me, I thought that the altitude had affected my hearing,” Jack said, giving himself a demonstrative belt on the head. “Claustrophobia!”

He disappeared within the tent once more, and the grateful Cindy thought he had gone to fetch her a blanket. “Not my man! He put on his own pea coat and came back to ask me what this was all about.”

“Well, Cindy, it was about a thousand degrees below zero, and I didn’t want to catch cold. After all, I do have to sing in It Happened One Night.”

What it was all about was exactly what she had said, claustrophobia, and no amount of persuasion was going to get Cynthia back in that tent. After a time Jack gave up and brought her sleeping bag outside. When he wormed his way into the tent a second time, Cindy assumed that he had gone after his own sleeping bag but he hadn’t. Jack had simply gone back to bed.

‘Warmer in there,”.he pointed out. But he couldn’t sleep, thinking of Cindy lying outside by herself, so he hauled his sleeping bag out and, without a word, lay down beside her.

Cindy was feeling a little foolish and largely apologetic. “Jack, I’m sorry.”

No answer.

“Jack, it never happened before. You know it didn’t.”

Practically tearful, Cindy turned her head to look at him. Jack was sleeping like a baby.

They don’t tell you how the grandeur of the Sierras moved them to awe—that might sound phony. They don’t say how wonderful it was to lie under the stars, talking about the things that matter—that would be too personal. They don’t even tell you how many fish they caught, because there were so many that that might seem boastful. They tell instead about the problems.

Jack says. “We came back to find a little stranger in the house. Before we went away Chris and I had a great father-and-son relationship going. We were Pals. Now he’s in that total-independence phase. We got home, I rushed in with outstretched arms, at which time Chris said, ‘Glub gluow,’ and staggered off to keep an appointment with two other guys.”

Wanting a better topic of conversation, Jack might even tell you about the tribulations Impi had with Duffy while they were gone. Duffy is the fifth and last member of the family, a pooch, and her outstanding talent is for doing the wrong thing at the wrong time.

But anybody who’s spent a day at the Lemmons’ can read between the problems to see that Jack, Cindy and Chris haven’t really got a worry in the world.

THE END

—BY ALICE FINLETTER

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955