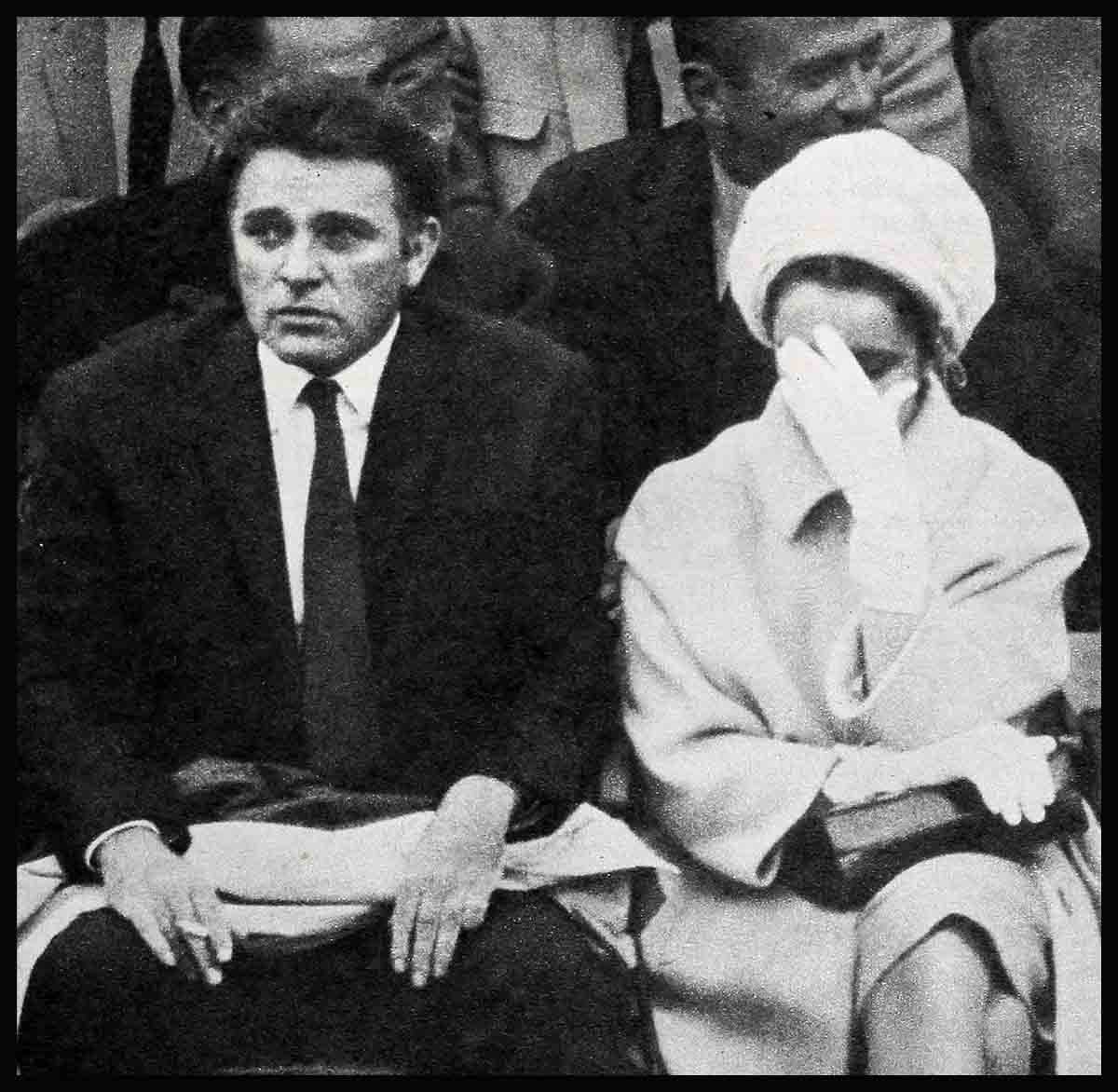

Richard Burton Two – Timing Liz Taylor!

To the seaside town of Aberavon—not far from Port Talbot, South Wales, where Richard Burton’s sister Cecelia lives—did Burton take Elizabeth Taylor one day early last September. To the scene of his boyhood fun he led her—where one could still stroll along the wide boardwalk and smile down at the groups of happy-faced biddies who sat on gay-colored beach chairs, in small, tight, semi-circular clusters on the sand, so as to protect their already ruddy complexions from the stinging breezes that swept in from the Bristol Channel, behind them; where for nine pence one could still buy a small but succulent beef-and-kidney pie, not to mention a cup of piping hot tea or a warmish and darkish glass of beer; where for another

few pence one could still ride the bang ’em cars, the creaky and timeworn caterpillar, and, of course, the wonderful, ancient carousel.

“Give it a go?” asked Burton of Liz at one point—indicating the carousel and smiling. Liz nodded, not smiling. “Get aboard, then,” said Burton. Silently, Liz climbed on.

Suddenly a tin organ began piping its merry and empty little tune ; suddenly the carousel began to move. “Aren’t you coming, Richard ?” Liz called, a bit nervous.

“No,” he called back, laughing, “—you take this one alone, sweet.”

And so she stood there now, clutching to a cold pole—roundabout, roundabout the carousel moving—catching small glimpses of him every twenty seconds or so—him standing there laughing, waving, as if without a care in the world . . . though she knew that in his heart of hearts there was no laughter this moment, not really . . . that he was acting now . . . superbly . . . like the most glorious of Hamlets—having a love affair with his own fears, and guilts . . . and yet horrified by them. And with her continuing to catch sight of his face—fleetingly . . . there he is . . . (tin music) . . . there he is ! And with her wondering, hurt and silent, if this old toy on which she now stood was not somehow a parody of both their lives this past year and a half of their much-celebrated love affair . . . this constant movement . . . this not always merry merry-go-round ride they’d been on, together . . . ever spinning, ever moving, never stopping for a moment . . . and yet an aimless and directionless journey. To where?—she wondered. And to what end? They had arrived in Wales—Liz and Burton—the preceding Tuesday. And she, for one, had been happier then. After all this time—though she had met Richard’s brothers Graham and Ivor Jenkins in London, plus a scattered assortment of cousins and distant relatives—Richard was now taking her home to meet Cecelia. Or, more widely and affectionately known as “Sis”—the oldest of the eleven Jenkins children. Who had taken care of young Rich ever since he was two, when their mother had died. Who had been from that time, therefore—though only seventeen or eighteen years older than Richard—as a mother to him. Who now lived with her husband, Elfred James, a retired miner, in a handsome house—“a lovely present from my brother.” And who would obviously be the one to give her “official” blessing to any forthcoming Elizabeth-Richard marriage—since, as someone in Port Talbot remarked to us, “for a Welshman to take a girl home is akin to getting engaged to her!”

It is no secret, of course, that for many months now Liz—like the rest of the world—had been confused about Burton’s actual intentions towards her. Quite confused.

There had, after all, been the days—the good days—when he had insisted, after a ten-hour stint at the studio working on “The V.I.P.s” that, instead of retiring to their suites for a leisurely pick-me-up, Liz sit with him—full-glare—in the lobby of their London hotel, the Dorchester, so that all the world could see her—and him—together—happy—Richard Burton with his prize, his pride.

And then there had been the days—the not-so-good days—when, after a row, he’d downed perhaps one too many—without Liz—and had said in his anger to whoever would listen (and once there was a reporter present): “That woman has no feelings. No feelings at all!”

There had been the day—it was just last summer, early—when, with Liz standing alongside him, smiling- and content on that day, sipping champagne, he’d proudly announced to reporters that “yes, we’re getting married—this wonderful girl and I.”

And then there had been the day—the very next day—when he’d announced, abruptly, to the very same reporters that he’d only been “jesting,” that he actually had no immediate plans to marry Liz Taylor—or anyone else, for that matter. (“I am still a quite married man, don’t you know,” he’d declared.)

There had been, at the time, those people of cynical mind who’d thought that this sequence of scenes and announcements and counter-announcements had been a grandly-played though weird sort of gag—cooked up by Burton and Liz in order to keep the admittedly-nosy world guessing. But the truth of the matter is that Liz had been as uncertain as anyone else about her loquacious lover’s intentions. Until the day he’d taken her home—to Sis. . . .

They’d been great fun. those first few days in Port Talbot. Liz—as someone has noted wryly, “ever adaptable at making herself at home with the new in-laws-to-be, whether Hiltons of hotel chains or Fishers of Philadelphia middle-class milieu”—formed an immediate and deep-seated rapport with the lovely and gentle Sis.

On arriving. Sis had prepared a lunch of scrambled eggs and lava bread (Richard’s favorite noon meal). And then—with Richard off in his Rolls to look up some old chums—Sis had taken Liz on a tour of the nine-room house, pointing out especially the small ground-floor bedroom “that is always reserved for my brother . . . when he gets the feeling he’s just got to come back home, back to his roots” . . . and then, upstairs, showing Liz the large attic-type room, the walls of which are lined with photographs of Richard . . . Richard as a boy, Richard when he was in the RAF, Richard in a scene from his first film, Richard when he played his brilliant Hamlet—the Shakespeare Hamlet—Richard through the years that followed.

For the rest of that afternoon, the two women had then sat—downstairs again, in the living room off the kitchen, rear of the house, with a large picture window facing a lush and lazy meadow, scarred only by the remnants of an abandoned mine shaft, a bleak memory of the Depression days when South Wales was one of the most impoverished lands in the world, when Sis and Elfed and young Rich had lived in a tiny house up on grim Taibach Hill, when to feed three mouths properly of a day was a challenge, a dare, an almost impossibility sometimes . . . and, sometimes, a downright, absolute impossibility.

At home with Richard and Sis

Sis had recalled those days to Liz now—an intently listening and interested Liz. And then, after a while, they’d gone on to talk about more happy things. In friendly and casual fashion.

And so had that first afternoon . . . those first few days . . . passed—pleasantly, very pleasantly, for Liz.

Long calm days with Sis, at home.

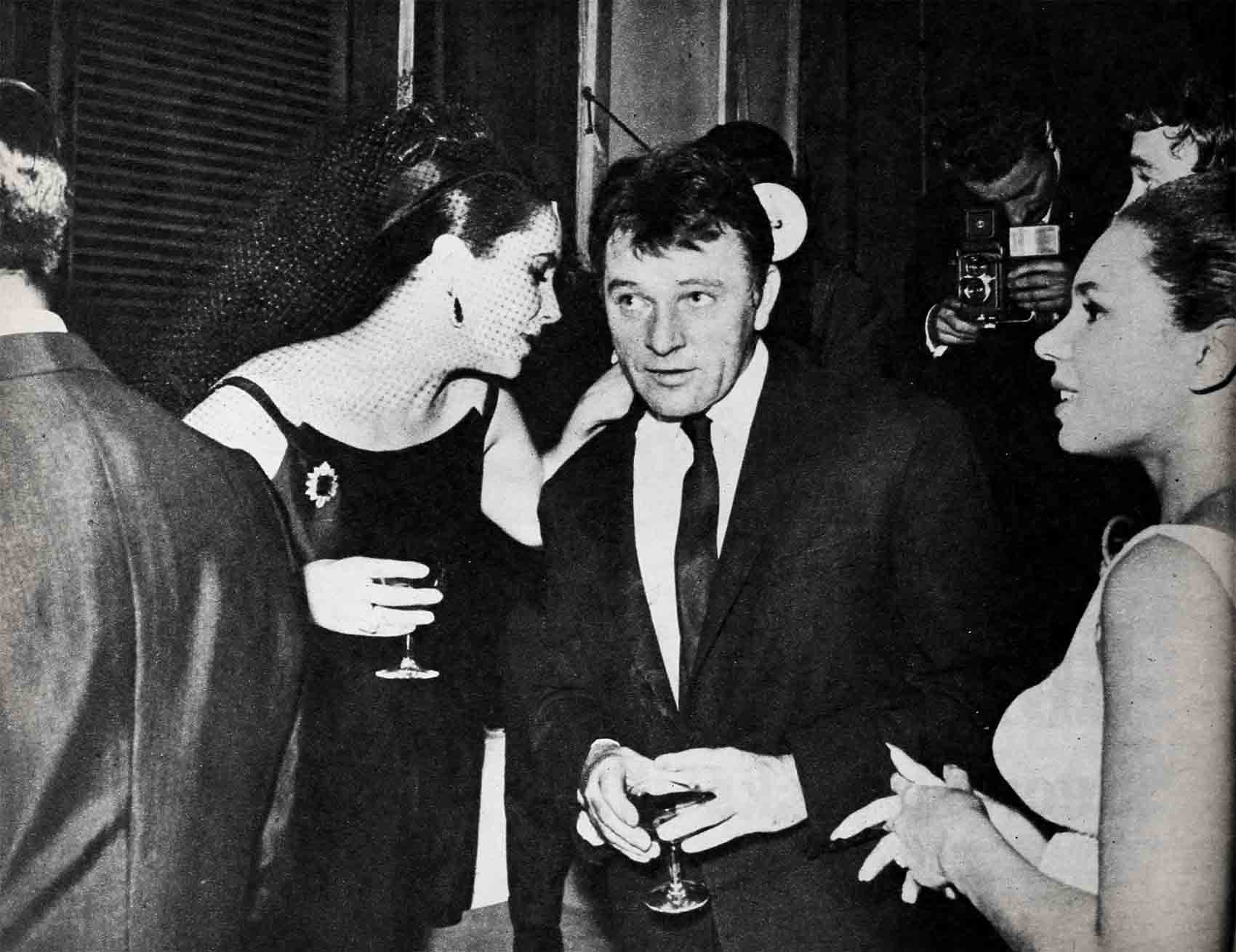

And long lusty evenings out with Richard—pub-crawling with him. Visiting his old haunts with him. Meeting the boys, the old friends, the miners, the tavern owners, the bar wenches he had told her so much about. And happy to see him so happy now—back with his people, who worshipped him . . . and whom he adored.

Not minding when—playfully, loudly—he would begin to “insult” her, publicly, as had become his wont lately (—as in the Playboy magazine interview with writer Kenneth Tynan, when he said, typically: “All this stuff about Elizabeth being the most beautiful woman in the world is absolute nonsense. She’s a pretty girl, of course—and she has wonderful eyes. But she has a double chin and an overdeveloped chest—and she’s rather short in the leg!”)

Laughing heartily along with the others when he told story after story about himself. and her:

“So there we were—just last week. Watching the ponies run—at Sandown Park. Elizabeth, I and good old Stanley Baker (the actor—also Welsh). And comes the moment Elizabeth says to me, ‘I want five pounds each way on such and such a horse.’ And I, of course—I didn’t look around at her. I simply said to Stanley, ‘You give her the money, chum.’ And Stanley answered, ‘Oh no, man—not on your life. I may never see her again. You’re the one who’s supposed to be with her the rest of your life. You give her the money!’ And with that—and very reluctantly, I don’t mind adding—I counted out ten pounds from my wallet. And handed them to my high-betting friend here!”

Ha-haaaaaaaa! Ha-haaaaaaa! !

And the laughter, uproarious, resounded through the pub now.

Liz joining.

Liz laughing. . . .

This then was the happy Liz in Wales.

But in London—days later, as before—there was a different Elizabeth Taylor. A frightened woman—afraid of what was beginning to happen, subtly, between her lover and herself; a woman—always possessive—who now began to cling more desperately than ever to the man she thought more and more was beginning to tire of her—whom she feared was, in turn, beginning to grow afraid of her.

For Burton, according to intimates—ever the free soul, coming and going as he wished, apologizing to no one for anything he ever did or said—he came gradually to the realization that Liz—unlike Sybil, unlike any of the countless other women in his life—would never let him go, leave his side, give him any time to himself.

A typical day in their lives during the time Burton was filming “Becket” went very much like this:

Liz would awaken at about 9:30. Have breakfast in bed. Then bathe and dress—between 10 and 11. Have a quick session with her secretary to discuss the mail, any problems. And then leave her Dorchester suite and get into her Rolls for the drive to the studio where Burton was filming, arriving just in time for lunch.

Because Liz doesn’t like to eat in studio commissaries—and because she doesn’t like to share Burton with anyone (most actors, while filming, normally have lunch with a co-star or two, their director, perhaps their producer, etc.)—she would then suggest that they drive together for a leisurely lunch at a nearby restaurant, where she had already made a reservation.

Lunch over, she would then return to the studio with Burton and spend the rest of the afternoon there, watching him work.

Then, at about 6, the day’s work over, they would return to London, usually stopping off for a drink on the way; they would then change clothes—Liz usually into a new Dior or Givenchy she’d picked up on one of her frequent but very brief trips to Paris (forty-five minutes from London by jet). And then they would dine more often than not at the Salisbury—their favorite pub, on colorful St. Martin’s Lane (dinner usually consisted of beer and cold roast pork). And then it was off to the theater—or perhaps a party—or, if Richard had his way, a visit with one of his old cronies, Welsh actors usually, whom he had known from his pre-Liz, pre-“Cleopatra,” pre-superstar days.

It is from several of these cronies, in fact, that we learned of the fears and the doubts and, indeed, the torments that were by now beginning to overwhelm Burton.

The change in Burton

Normally a master raconteur and joke-teller, his friends noticed that he talked less and less of an evening now, that he often appeared “morbid and preoccupied.”

Normally merely a “good drinker,” they noticed that now he was beginning to belt down the booze too fast and too often.

As one of them has said: “Towards the end of an evening, he would often tend to become more and more irritable with Liz—reminding her that he had to be up early the next morning in order to get to the studio on time, that he had lines to learn—accusing her of wanting to live it up when he needed rest, time to think, time to be alone.”

The story is told how, prior to leaving for Mexico and work on “The Night of the Iguana,” Burton had a change of heart and told Liz he didn’t think it advisable that she come along.

“It’ll be hot there,” he reportedly said. “We’ll be doing rough locations for two months. We’ll have trouble finding an adequate place for you and the children. Why don’t you—”

But Liz didn’t give him time to go on. Interrupting him with one of her violet-eyed looks, she said simply: “I thrive on travel—and I’m coming.”

And that was reportedly the beginning of an argument that is probably best left unprinted!

According to other friends of Burton’s, however, these were just surface excuses for arguing.

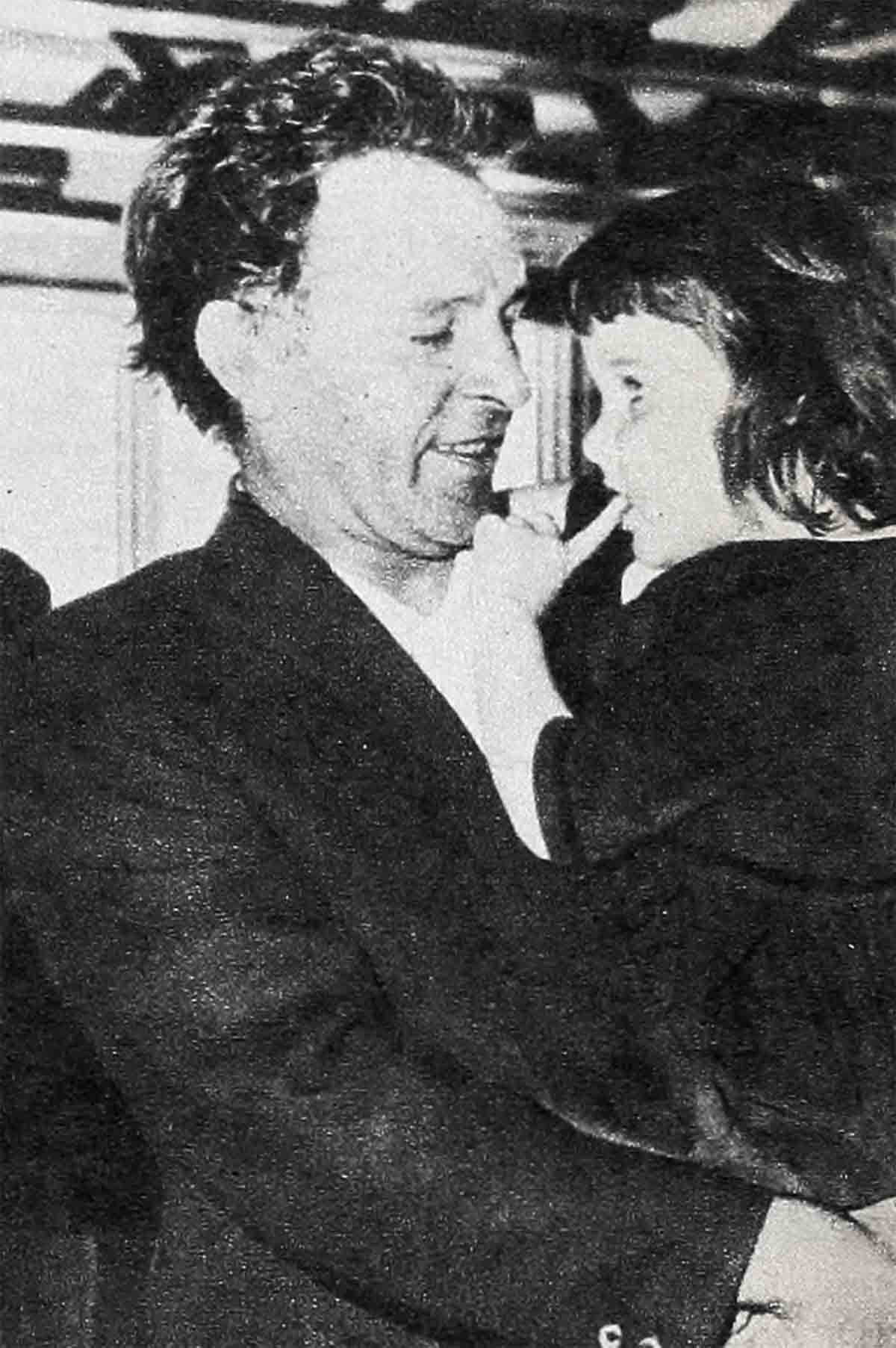

Because the core of Richard Burton’s trouble lay deep within him, coming to a head, ironically, but sharply, during the period late last summer when Elizabeth’s children—Michael and Christopher Wilding, Liza Todd and the little German girl Liz has adopted. Maria—came with their nurses and nannies from Liz’ chalet in Gstaad. Switzerland. To spend some time with their mother. And. of course, with Richard Burton.

At the beginning of this visit, say friends. Burton couldn’t have been more delighted with the children. He played with them, read to them, took them on picnics, invited Liz to bring them to the set.

“But then,” says a friend, “it must have suddenly hit him that by playing father to Liz’ kids he was more and more reminded of the fact that he was no longer a father to his own children. Kate and Jessica—by now long in New York with their mother.”

And so the guilt continued to pull at him. And so the doubts continued to grow.

The arguments with Liz grew louder, and more violent.

It was as if Burton were ready to shout out to Liz: “You are consuming me. and I don’t want this. You are taking away from me everything that I love and want in life. My children. My freedom. My very essence, my manhood!”

One day—in the midst of one of these depressions—Burton had drinks with a close friend, just back from New York.

With purposeful casualness. Burton asked the friend how Sybil was getting on. “Did you run into her? Hear anything about her?”

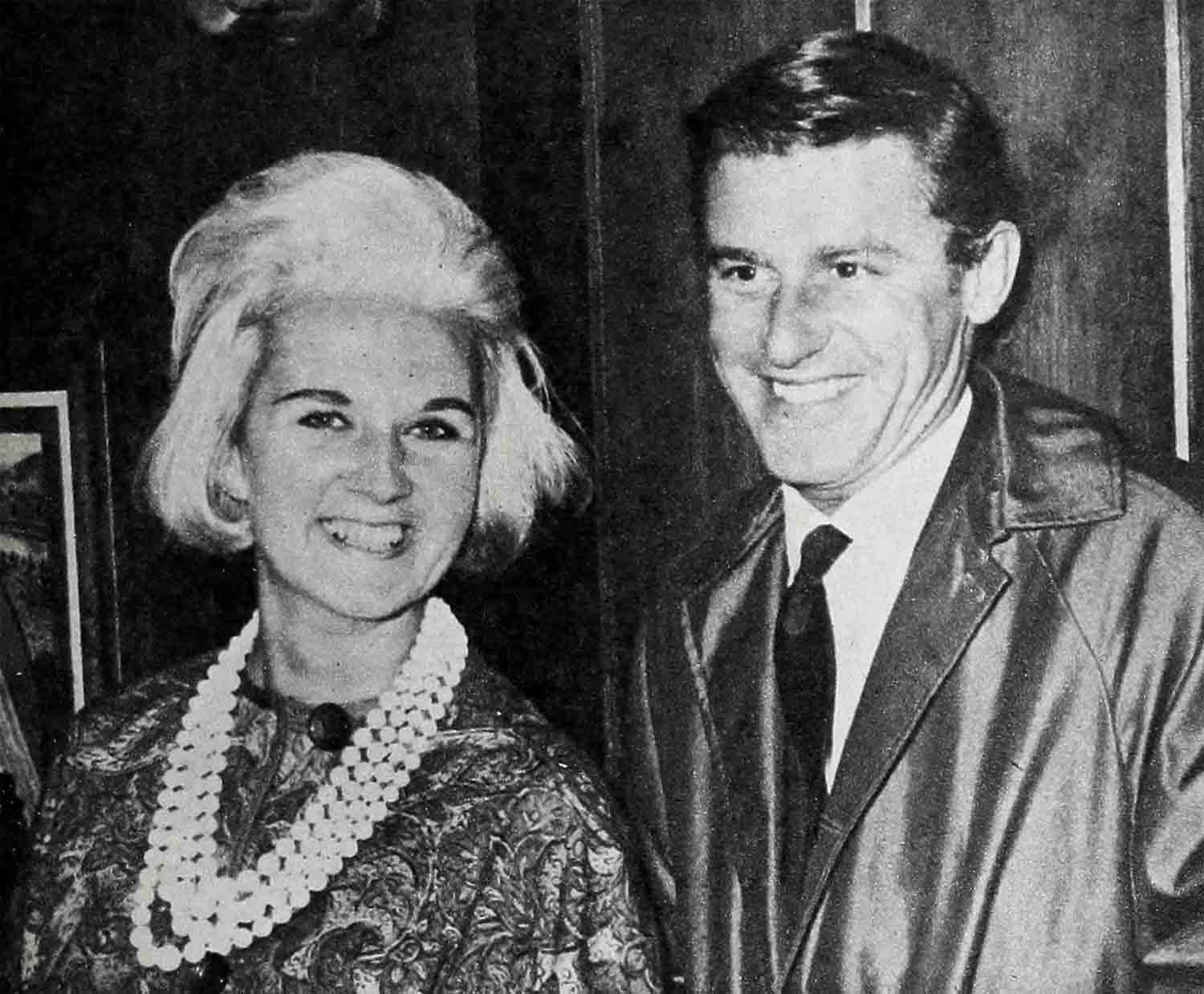

And the friend answered, “If you’re worried about her, Richard, you needn’t be. Syb’s doing smashingly, having a whale of a time. She has a lovely apartment—twelve rooms, quite lavish, overlooking Central Park. She enjoys taking the children out by day—being with them. And at night she goes out—constantly—to all the happenings—the night-club openings, the picture premieres. And she has become a celebrity in her own right now—stopped for autographs here, there, everywhere. Recognized as soon as she enters a restaurant. Exceedingly well liked. Happy.”

The news delighted Burton, at first—but later, when he thought about it, he must have been pained that for the first time in her life, Sybil was “getting along fine” without him. Without her husband!

Two-timing Liz

That night, alone in his suite—one of his few moments away from Liz—Burton did something that no other man had ever done to her before. For who had ever dared two-time Elizabeth Taylor?

He picked up his phone.

He asked the operator to get him New York—Sybil’s number.

And without wasting any words—point blank and to the point—he asked Sybil to come back to him—just for a month or so—at least—and with the children.

Sybil’s reply was equally to the point: “Don’t be ridiculous, Richie.”

It is not hard to imagine Burton, at this moment in his life, sitting there, three thousand miles away from his wife, holding the receiver in his hand, stunned. Always, always in the past this was all that he’d had to do. Phone Sybil. Ask her to come back. And a-running she would come.

But now, for the first time, he realized that things had changed. That the woman who had stood by him for fourteen years—forgiven him, taken him back with warm and wifely embraces—was no longer willing to put up with that scene. That she’d had it—once and for all. That she’d learned to live away from this husband she had loved so much. That gone were the days of the urgent SOS’s, the quick trips back—the vows that “this will never happen again, my darling—believe me.”

Nor is it hard to understand why. soon after this abortive phone call on Burton’s part, did his attitude towards Liz suddenly seem to change.

Says a friend, “These past few weeks he has been absolutely a different man with her. On one hand, one might say that he has capitulated to her. While on the other hand, one might wonder if he hasn’t come to realize that should he continue to play ‘rough’ with Liz—he is just liable to end up losing her. along with Sybil.”

At Liz and Burton’s Toronto stopover, en route to Mexico and “Iguana,” Liz told reporters, “I’ll be Mrs. Burton in three months.” Burton made no comment then, but in Mexico, denied the whole thing.

Meanwhile, in New York. Sybil’s attorney upheld “no divorce contemplated.”

As we go to press, word comes that Burton has just signed a contract with a New York producer to play his famed “Hamlet” on Broadway, beginning next March and through next June.

Married to Liz by that time or not. that will give him some three months in the same city with his children—and with his perhaps by-then former wife.

Would it be unlike Richard Burton to pick up his phone one day then and—not from three thousand miles away, but from perhaps three short blocks—ask Sybil if he mightn’t see her for a while?

Would it be unlike Richard Burton—perhaps after arguing with Liz Taylor over the tensions that will undoubtedly continue to plague him and their lives together—to then, once again, ask Sybil to take him back? Two-timing Liz again?

We feel that the answers are obvious.

Especially since the questions posed are based on the practically unimpeachable information we have been receiving these past few weeks.

Apropos of this information. Photoplay phoned “Sis” James, trans-Atlantic, the other day to ask whether she might be able to shed any light on the situation.

We began to ask our questions. But Mrs. James said that she would not talk about any personal matters concerning her brother. The only thing she would say was that “Richard is a kind and generous man, always thinking about the family. His happiness naturally comes first in my mind. . . .”

Not far from Sis’ house, meanwhile—over in seaside Aberavon—a carousel continues to spin to empty music.

Still roundabout, roundabout—and in aimless and directionless circles.

THE END

—BY DOUG BREWER

Liz and Burton appear together in 20th’s “Cleopatra” and M-G-M’s “The V.I.P.s”. Burton’s next film is “Becket,” for Para.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1963

No Comments