Liz Screams! Mob Beats Up Burton!

“I say, Richard, I’m calling from New York . . . tell me, how is your eye? Is it very bad?”

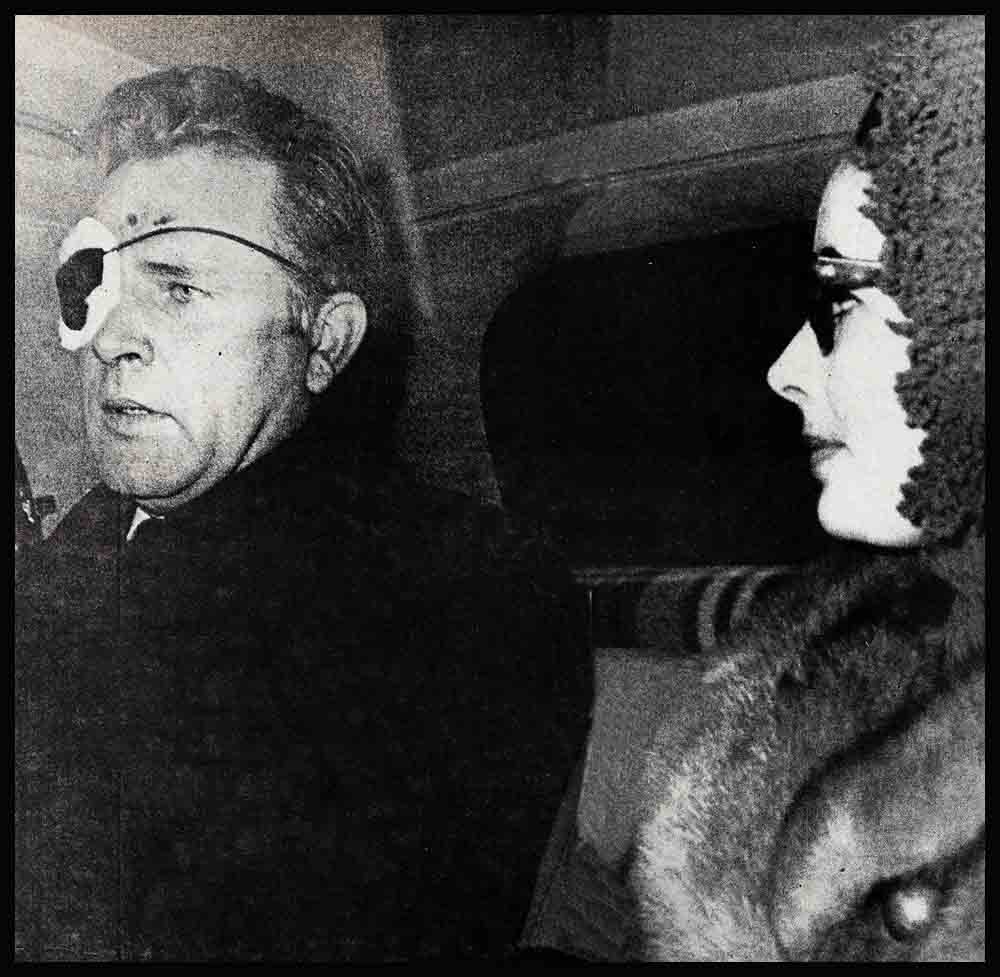

I was calling Richard Burton. He was in his diggings in London’s elegant Dorchester Hotel; nursing a black eye, cut face, bruised body, aching back and worst of all, injured dignity.

Liz Taylor was at the Dorchester, too, lending Richard what we might call “moral support.” She was much calmer now. Her screams of horror and shock at the sight of the wounded Burton had long since subsided.

But Liz was indisposed herself and at the moment, for all we know, Richard may have been readying some “moral support” for her. She had just returned from the hospital where she had had a forty-five minute “manipulated operation”—about which we will have more to say later in the story.

For now, let’s concentrate on getting the facts on Burton’s bruises and injured dignity.

“What prompts you to awsk?” Britisher Burton awsked in reference to my inquiry.

At four pounds (about twelve dollars) for the first three minutes, plus a seventy-five cents charge for a person-to-person call, I came to the point quickly.

AUDIO BOOK

“I have a report here that you were done in by the ‘Teddy Boys,’ ” I burbled gently. I didn’t want to make it sound like a presumptuous offense. It was not my intent to shatter Burton’s equilibrium. Heaven knows, he was already shaken enough.

“I’m trying to find out how badly you were hurt.” I continued.

“Ah, well,” Burton murmured, “it was just one of those awkward things that can happen anywhere. Happened right outside Paddington Station—with relays of people passing. It was quite frightful, I really must say.”

“Indeed it must have been a frightful experience for you,” I buzzed. “I hope you had those incorrigibles locked up.”

Burton grumbled. Sounded like he was trying to grin and bear it.

“No time for that,” he said calmly. “They rushed off . . .”

He was warming up to the interview. I savored the prospect of getting a Photoplay exclusive on the details of the cuffing administered to Burton by the “Teddy Boys” —London’s equivalent of our juvenile boy mobs.

“Could you tell me how it happened?” I pressed on industriously—as a good reporter should.

“Not really much to tell,” Burton rebounded nonchalantly, as if the episode had not galvanized much afterthought. “It happened so quickly that I’m still put out in finding any logic to it all.”

“You were returning from a soccer game when it happened?”

“Ah, not that, it was rugby . . . the England-Wales rugby match which was played in Cardiff.”

Burton related that he had gone to the Saturday afternoon game and returned in the early evening to find people standing stoically in the bus and taxi queues outside Paddington Station.

“The snow was crisp and even—and there wasn’t a thing in sight,” he remarked about London’s transportation in the midst of the country’s worst winter storms in years. London had been digging out of knee-deep drifts for days. The city’s transit facilities were, as a result, still in a state of near-paralysis.

“Some of the people were taking it philosophically,” Richard related. “They were resigned to the fact that they couldn’t get any colder in that perishing weather and their only way of getting home was to stand put hopefully and wait for something to come along. But some people were cursing their plight.”

Burton saw his cue at the queue to propound his philosophy about the inordinately trying situation. Now, here’s how he told the story of how it all happened:

“I muttered about this marvelous public service London has and said a word or two about its taxis . . . I don’t remember exactly what it was I said. Perhaps I was a bit vitriolic in spots about the cocky independence of all the cab drivers over here in London.

“I was talking to ordinary people and I thought I was being rather cheerful.”

Burton said sheepishly that he didn’t “cotton on to” an unseen little mob of boys who had snuggled up pretty close to him.

“Suddenly . . .”

He paused, as if trying to dramatize the punchline. Or perhaps he was trying to get over the shrinking horror of his calamitous encounter with the mob of young ruffians. Whatever the reason, Burton resumed the story:

“I was surrounded by a half dozen little boys . . . you might say they were ‘Teddy Boys.’ You know, little toughies. They bunched around me and before I could express even mild curiosity about their presence or their motives, I was caught right in the middle of a very tight scrum.”

Having just returned from a rugby match, Burton was fitting the game’s jargon to the situation. A “tight serum” is formed by the eight forwards on both sides in two or more rows to shove against each other as soon as the ball is put on the ground between the two rows. The serum half is the one who puts the ball down.

Looking rather loosely at his predicament in Paddington Station, one might visualize Burton as the ball—although he is hardly what you might call leather-covered and oval. Nevertheless, one of the “Teddy Boys” handled Richard with all the blandishment accorded the ball.

“Somebody started lunging out,” Burton said with increasing feeling. “I was caught off-balance and felt my feet giving way. Then a really small boy got me on the ground. . . .”

I sensed it was paining Richard considerably as he relived those delicate moments.

“Did they ‘spin’ or ‘hook’ you?” I broke in. I was borrowing rugby jargon to spear jocularity into the tensing atmosphere a building in our trans-Atlantic telephone cables.

“Hook me?” Burton groaned. “They bloody well kicked me! I was damned helpless . . . lying on the snow unable to move . . . helpless, I tell you. . . .

“They just kicked and kicked me . . . all over.”

I sympathized with Richard. I told him it was outrageous and I let out a primed gasp when he remarked that the onlookers made no attempt to break up the assault. I said:

“Why I think those blokes in the queues are just as much to blame as the ‘Teddy Boys’ for perpetrating an assault with intent to cause bodily harm (that’s how they sling it at Old Bailey).”

Burton grunted. I couldn’t tell if that was a nod of agreement—or something he ate.

“I just don’t know what to make of it,” he commented after a brief moment of silence. I am afraid I cannot fathom it . . . I am at a loss for an explanation, really.” There was another silence.

I asked Richard what he did next.

“Why, I picked myself up off the ground, of course,” he replied wryly. “And I took stock of my injuries . . . I found I had a cut over my right eye.”

“Did you go to the hospital?” I asked.

“No, it wasn’t that critical,” Burton answered with a sigh of relief. “I went to my hotel and called my doctor.”

“Tell me,” I put in curiously, “did you get your cab?”

“Yes, damn it, finally!”

I then inquired about Elizabeth Taylor’s reaction to the sight of Burton’s blinker.

“Oh, well,” replied Richard, “it was rather shocking to her. You know we’re making ‘The Very Important Persons’ together at Elstree. My injury forces me out of production for several days—unless the director should choose to incorporate the flavor of a black eye into the script. But I hardly think he shall. . .”

I wanted to know what Liz did when she got a gander at the dusky peeper.

“I don’t really recall,” Burton said with a chivalrous air. “But she was quite disturbed, as I remember it.”

However, reports from London indicated Liz bit high “C” when she saw Burton after his run-in with the “Teddy Boys.”

I also tried to reach Liz at the Dorchester. But it was as if she had gone to Tanganyika. None of her coterie of secretaries, nurses and flunkies could say when she might come to the phone.

Nevertheless, with dedicated scribes like Douglas Marlborough of the newspaper The London Daily Mail on the job, the momentous words of Liz Taylor remarking on the blinker those little London blighters hung on poor Richard shall not go unrecorded.

Mr. Marlborough intercepted Burton and Liz at the stately gates of Lord Dynevor’s London home as they were going in for a meeting of the new Welsh National Theatre. Ordinarily, Mr. Marlborough might have chronicled the couple’s appearance at Lord Dynevor’s with a paragraph or two which would have been buried somewhere back in the paper. It must be realized that Liz and Burton are no longer an “item” in the newspaper offices of Fleet Street, Holburn Circus and the Embankment. They’ve been together so long and so often that the press, as one irreverent wag was heard to comment, has come to regard them as much a fixture of British legend as, say, the King’s African Rifles.

But when Liz and Burton showed and Mr. Marlborough spotted the black patch covering Richard’s eye, it prompted the newsman to make some discreet inquiries. Burton readily volunteered the story of his encounter with the “Teddy Boys.”

A man of considerable curiosity and sizeable determination to cover news incisively, Mr. Marlborough couldn’t pass up the opportunity to ask what Liz thought of the shiner.

Liz regarded the question plaintively for a brief while, drew a deep breath finally, and said:

“On my Nelly, I’ve never seen a black eye like that. Poor boy.”

Then Liz and Richard disappeared into Lord Dynevor’s place at 76 Eaton Square.

Oh, yes. I must report I was unable to obtain any remarks from Richard’s wife, Sybil Burton. Sybil hadn’t yet seen her husband’s eye. There also was some speculation as to whether she would. Black eyes heal quickly, as a matter of medical fact. If past recent history holds any lessons for us, the odds portend very little likelihood that Mrs. Burton will see her husband before the discoloration disappears.

Burton, you see, might be too busy staying at Liz’ side while she’s recovering from that “manipulated operation.” That’s what the doctors at London Clinic called it. It might sound like a serious bit of surgery, but it wasn’t.

The fragile beauty who has experienced far greater crises in hospitals during her life, seemed to enjoy this hospitalization.

“The trouble began,” Burton said, “on the set of ‘Very Important Persons.’ Seems Liz’ knee either twisted or turned somehow and she suffered a ‘locked cartilage.’ It was so painful she could barely walk.”

The studio called the hospital at once and a room was prepared for the beauty who appears to walk hand in hand with illness. She was driven to London Clinic in a studio limousine. Before Liz entered the clinic, she posed jauntily for a picture. She came well prepared for the photographer in a light suede sheeplined jacket, fawn colored riding pants, high-heeled, calf-length black boots with red borders at the tops.

Dr. Robert Young, an orthopedic surgeon, and two assistants then took over. Liz was wheeled to surgery, administered a general anesthetic, and her knee then was “manipulated” by the doctors back to its normal position.

“It was over in forty-five minutes,” Burton went on. “When Liz came to in her room, she felt no pain. Her knee was in a plaster splint which the hospital said would have to remain on for a few days.”

Liz may have recalled with somewhat of a shudder her last stay in London Clinic in the early part of 1961, when she came down with pneumonia and other respiratory complications. Her life then had hung precariously in the balance—almost by a hair. Doctors performed a tracheotomy to help her breathe—and that saved her life.

It was much different now. Said Burton, “Liz was alert and smiling.”

Liz broke into a grin as her eyes focused on the people in her room—Burton, the doctors and nurses. And there was champagne to celebrate her recovery.

When Richard toasted Liz for rallying so magnificently after her accident, little did they know that a fortnight later there would be bad news. The knee apparently did not respond completely, and Liz had to make plans to re-enter the clinic for major surgery to remove the troublesome cartilage. The operation would be simple, but the results could he tricky. No one would predict the outcome.

But as they drank champagne, then, these thoughts had not entered their minds. Liz smiled as she raised her glass to Richard, toasting him for having been so lucky to come out of his heating with only a cut and blackened eye.

When you think of it, Richard Burton is a fortunate fellow.

“Do you know,” he told me, “that one of those fellows even went so far as to put his bloody boot in my eye! Luckily, it wasn’t a winkleticker.”

“Uh?” I asked.

“What, my dear fellow, you don’t know what a winkleticker is?”

Now I know.

A winkleticker is the currently popular men’s shoe with the exaggerated long pointed toe.

No story about Richard Burton and Liz Taylor is complete without some mention of Eddie Fisher.

From Hollywood, where he was keeping a singing engagement, word came that Eddie had heard about Burton’s unfortunate experience.

It was reliably reported he had no comment—except that he was heard to mutter: “Mmmmm . . .”

—GEORGE CARPOZI, Jr.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1963

AUDIO BOOK