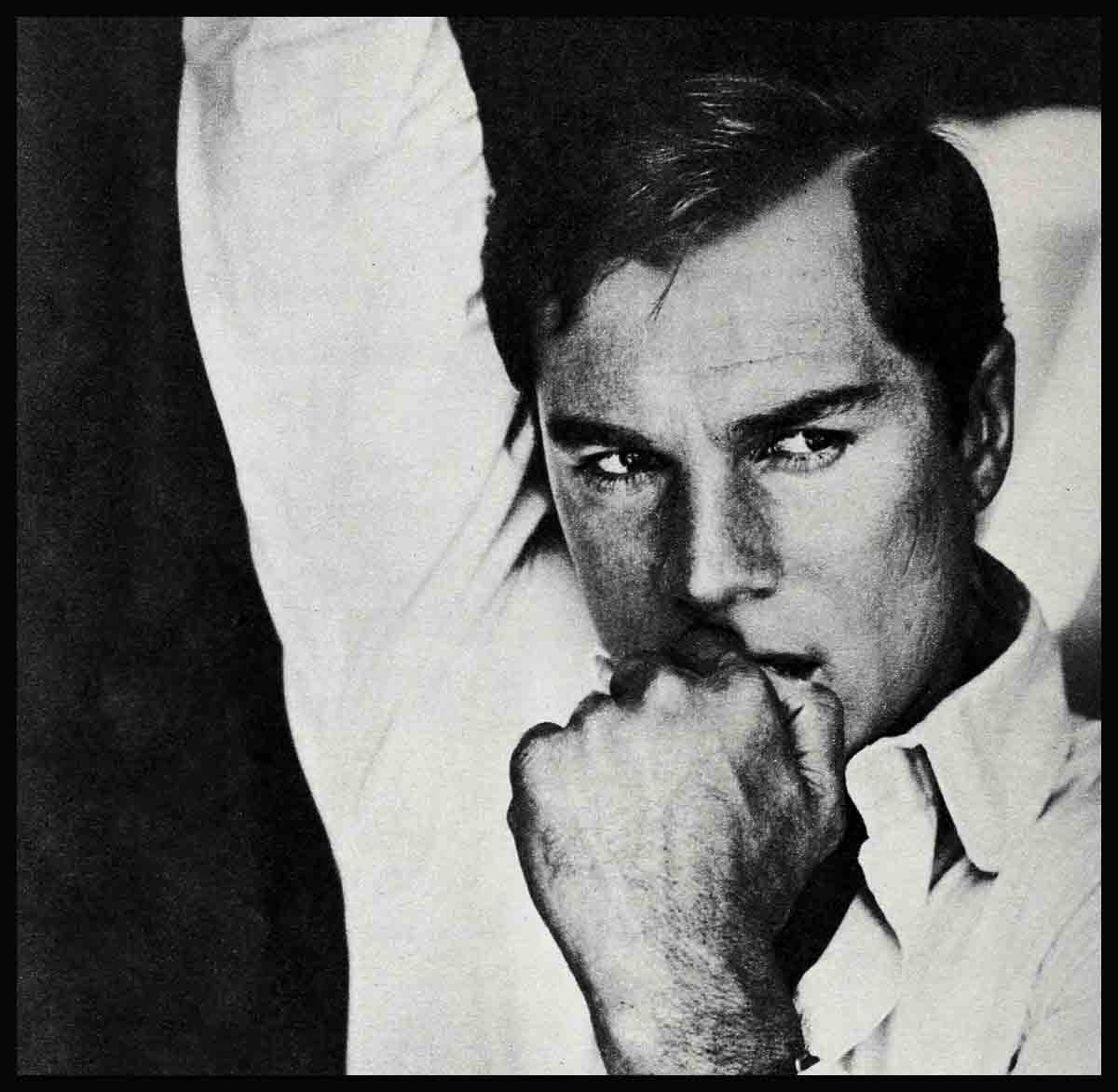

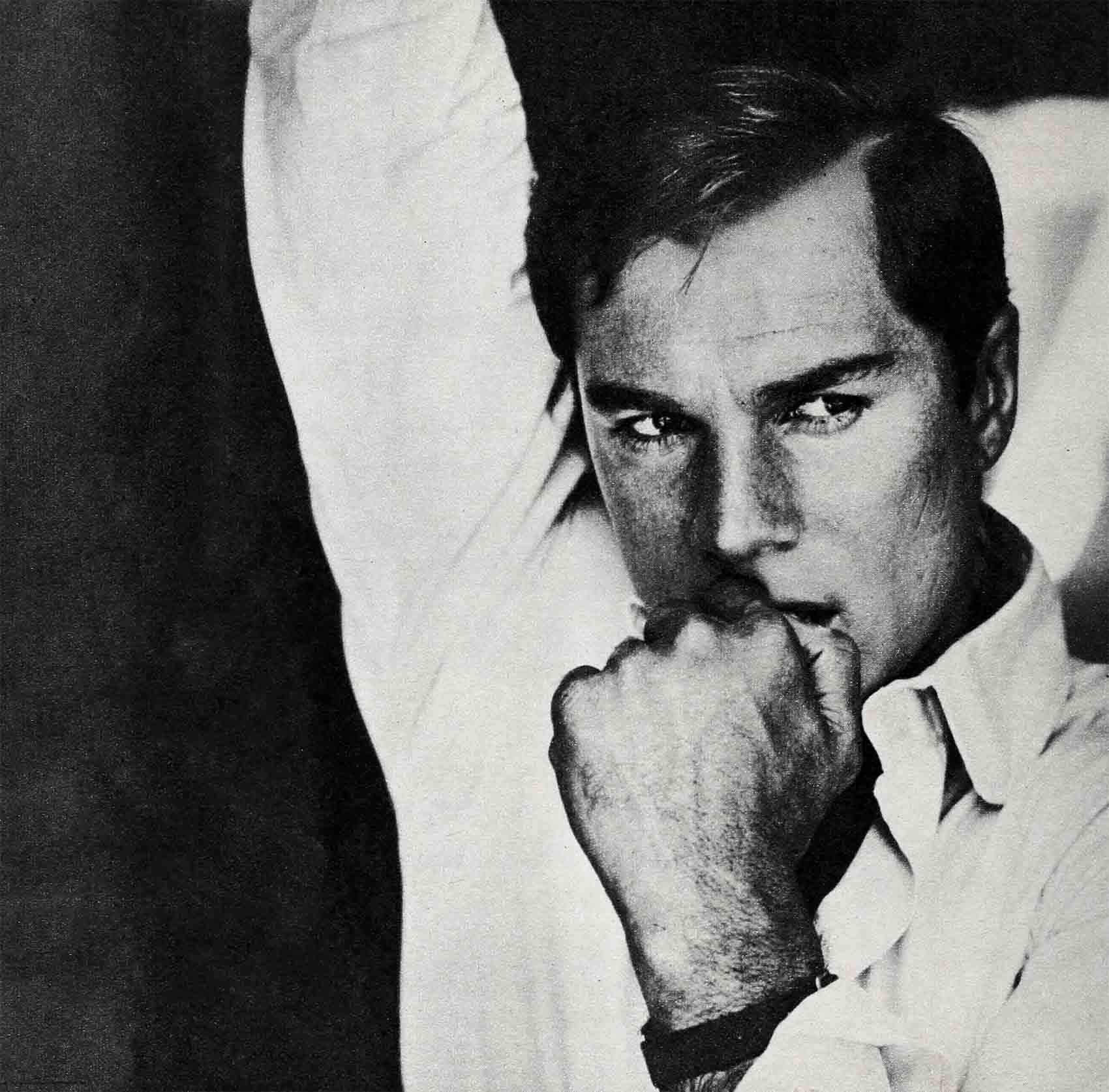

Sometimes Love Is A Hit On The Head—George Maharis

Sitting in the cramped living room of his tiny six-flight-walk-up apartment in the heart of Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen, George Maharis looked up and said, “I don’t want to live like this forever. I want a real home—a wife and a family.” He grinned. “Kids flip me.” The grin faded. “But I don’t know if it’s possible for me to marry. I never learned to make a good relationship with anyone—I guess you might say I never learned to love. Like everyone else. I’m a product of my early years.”

When he was a kid, George knew nothing but violence. It fed at his heart, and left it badly scarred.

In school, in Flushing, New York, the kids he knew vied for position and prestige. They made their mark by defying authority, not by high grades. The object was to get away with as much as possible when teachers turned their backs.

Outside of school, the kids made their own laws, and the gangs they belonged to enforced them. Anyone who didn’t belong to a gang was a target for everyone who did.

In George’s home, there was also an underlying violence that erupted when the pressures of hard times became too great to bear. When George was a boy. his father, a quiet, gentle man, lost the restaurant he owned. Creditors descended on the household, coming to the door at all hours of the day and night to wave bills and shout threats. To pay his debts, George’s father had to take jobs in other people’s restaurants. George’s mother went to work as a cleaning woman in Rockefeller Center, then later in a chewing gum factory. Both his parents fought a never-ending battle against weariness and fear and debt. and sometimes their shattered nerves rebelled.

The children in George’s family reacted in different ways. George’s older sister Mary found comfort in the Greek Orthodox Church, and tried to lead a Christian life. You could have stepped on her face. George believed, and she would say, “Oh, he didn’t mean that.” George’s older brother Bob found a way of life in passive resistance. He went his way quietly, and whenever the consequences were unpleasant, he took them without complaint.

But for George neither of these methods would do. The Church baffled him. Why should it ask money from the poor at every service? Why didn’t it give them money instead? No, he wanted no part of the Church. Nor could he accept his lot passively, as Bob did. When he was pushed, his instinct was to push back. Sometimes, it was to push first. Sometimes the pressures of bitterness, resentment and hatred built to such a point that fighting became a kind of welcome release. In self-defense. George gradually withdrew into himself. becoming proud and solitary, emerging from his aloneness only to strike out against the world—the world into which he’d had the misfortune of being born short, dark-eyed, poor and Greek.

He had no friends. His family was the only Greek family in the predominately Irish neighborhood. and George refused to join their gang. He had to be free, he told himself; he couldn’t be one of the “sheep.”

Between classes and at recess. he stayed to himself; he was too proud to let anyone—anyone in this whole darn tough world—get close enough to see the cardboard in his shoes, the patches on his shirts and trousers. Resenting his aloofness, his classmates stopped speaking to him at all. When they did, it was only to shout “Greaseball!” Then, George would wade into them, fists flying, unless he was too badly outnumbered. Then he would prudently run away.

Many times Bob would come home with a black eye or a bloody nose intended for George. Born only a year apart, the boys looked so much alike, the gangs would mistake them for one another. Bob knew he was taking a beating for George, but he never complained.

There was no justice . . .

To George. the fact that Bob took his beatings was only one more example of the injustice of the world around him. He had seen his mother almost die because of a careless diagnosis made in a city hospital ward. He had seen the baskets of fruit sitting lushly in the A&P when his own stomach was empty.

In the midst of a world such as this. George came to hate any form of authority—and to despise as “sheep” those who. without authority, allowed themselves to be pushed about. One could be strong, he came to believe, only by being entirely alone, dependent on no one (for everyone failed you), free of attachments to things as well as people (for things cost money and money was hard to come by). And to survive in his world, one needed to be strong.

Eventually his parents were unable to control this sullen, unspeaking, uncooperative son of theirs. Their lack of communication became most terrible on the day when George somehow drove his mother to such a state of frustration and anger that she threw a dinner plate at him. It hit him in the back of the head and blood rushed out like a fountain. His mother was horrified at what she had done. “I’ll fix it.” she cried. But he would not let her near him. Wanting to punish her, he chose instinctively the cruelest way he knew. He warded her off until she wept, and then, his shirt stiff with blood, he walked out of the house. In the garage was an old car, bought in better times. George climbed into the back. The garage had no heat. but he stayed there for hours. shivering as much with hate as with pain and cold. After that, whenever he needed a hiding place—and he was always running from someone or something—he would sit in the car.

That was the tenor of his life. lonely and bitter. And all the while, love lay all around him, waiting eagerly for his word or gesture to call it forth. But George did not know the word, he never learned the gesture. He never knew how to let anyone help him, and he rejected the few who tried. People called him “the kid who never smiles.” His own family knew him as an angry stranger in their midst.

It was not until he was in his teens that he got his first inkling that the world contained anything but violence and hate. The summer before he entered high school, he heard of a children’s camp in the Poconos where busboys could get good pay as well as free room and board. One day without explanation, he asked his mother to give him a blanket; nights, he had heard, were cold in the Poconos. His mother refused on two accounts: first, she had no idea why he wanted a blanket, and secondly, there were barely enough for the family. George’s reaction was typical. He turned on his heel and walked out, letting weeks go by before he told his family where he was.

He hitchhiked to the mountains and got the job. At night he almost froze to death, but he didn’t complain. In his usual manner, he ignored or insulted the other busboys, so they quickly came to dislike him, as he knew they would, and to leave him alone, as he hoped they would. He was rough on the young boys at camp. “I’ll bat your head in, sonny! G’wan outa my way or I’ll drown ya!” was about all he said to them. Instead of running, the campers usually hung around to giggle, pretend terror or happily flail out at him with their little-kid fists. Whenever George had a free moment, he’d walk in the woods. Quiet, clean and private, they became his new hiding place. He taught himself to horseback ride and at night, when other camp employees drove into town, he’d take one of the camp horses and ride alone through his beloved woods. Since he had nothing to spend money on, he changed his tips and salary into big bills and—because his locker had no key—hid them all over his room.

When the summer was half over, some money was stolen from a visitor. The camp director questioned the employees individually. Almost unanimously they suspected the dark Greek boy who never smiled or talked. Finally they searched George’s room. Under his mattress, in the back of his closet, in an old pair of shoes, they found his horde of bills.

Pint-sized angels

Instantly the camp was in an uproar. George was hauled before the director and accused. He protested, but he knew it was useless. All his life he had been accused. When the director announced that George would be turned over to the police, George said nothing.

And then the amazing thing happened. The little campers rebelled. They loudly proclaimed his innocence, and stormed the director’s cottage, and argued with the counselors. When they were not heeded, they banded together to announce a general strike: if George was arrested, they wouldn’t eat!

The camp directors were alarmed. George was totally stunned. In all his life no one had ever believed in him, no one had ever risked anything for his sake. Now, out of nowhere, came a band of pint-sized angels proclaiming their faith in him—in the short, sullen-faced, friendless Greek. So overwhelmed was he that he hardly heard the director when he told George that since the “stolen” money was “recovered,” he had decided not to press charges; he hardly noticed that he and his belongings were hastily hustled out of the camp and onto a train back to New York. All he knew was that a brief glimpse of an unknown world had been given to him, and he was blind to everything else. He did not know that he had taken his first tiny step out of the self-imposed isolation in which he had always lived.

Back in Flushing, broke and alone, the old world closed in once more. But not as dark as it had been. A glimpse of light remained. It was to widen slightly that fall, when he began high school.

In his first week at school George ran smack into an old custom known as Senior Day. On that day, any freshman who wore red was hustled off to the auditorium by upper classmen to do penance. George, who had a red sweater, was captured and told that as punishment he was to get up on stage and sing. He couldn’t fight the whole school, so he obeyed. To everyone’s astonishment, including his own, he had a rather pleasant voice. They applauded him sincerely and called for more. Staring down at the smiling faces, it occurred to George that a mob was, after all, a pleasant thing to have on one’s side, and that it was possible that he had a gift for manipulating people. He looked around for a way to test this new possibility and found it in school politics.

Before he was out of his freshman year, he had organized a new political party in the school. He, who had so adamantly refused to join anyone else’s group, discovered it was quite a different matter to have other people join his. He excelled in clever ways to win elections. While other parties’ candidates made dull speeches—George’s led parades and coined slogans. Other parties sought the votes of “influential” upper classmen—George’s courted the impressionable freshmen who would be around for elections to come. With his new-found glory, George took his second step out of loneliness. On the surface, it was a big one. He was a wheel now, someone to be reckoned with. Everyone in school knew him, and most of his classmates respected him.

But below the surface, he was still alone, still untouched. He never ran for an office himself, explaining carefully that his grades were not good enough, but actually he preferred to be the power behind the throne, the power that manipulated the strings that moved other people. He had acquaintances now, but still he had no one in whom he could confide his fears or shames—no friends. The violence was still within him, but now it exploded only on the football field, where George told himself that the opposition line was the whole world. Fiercely, if secretly, he maintained his cherished independence. Especially where girls were concerned.

He had girls now. Pretty, popular ones, eager for dates with him. He could have his pick. And pick he did—by his own standards. If a girl looked as if she expected money to be spent on her—even the cost of a movie and a hamburger—she was out. He had no money. Whatever he made at odd jobs went to his still-struggling family. Most of the girls would have been happy to go Dutch or settle for school dances or afternoons at the city beaches, but George never dreamed of explaining anything to anyone. Instead, he simply dated girls who were unlikely to notice that no money was being spent. Finally he settled on one, a pretty girl named Toni. For a while he saw no one else. Then Toni did an unforgivable thing. She dropped by his house after school.

In the way of life George had worked out for himself, visits to his house by any of his acquaintances or dates were strictly excluded. A visitor might observe that his family had less than their neighbors and pity George. He always arranged to meet people at school or on a street corner. Sometimes he went to other people’s homes, but he never accepted anything to eat—that would put him under an obligation to return their hospitality.

So when he walked in one afternoon and found Toni—who had long wondered why she had never met George’s folks—happily chatting with his mother (who was delighted, at long last, to meet one of George’s friends) he turned white. Within five minutes he had hustled Toni out of the house. Not long after, she was out of his life. It was a painful breakup. but in many ways he and Toni were becoming too close—almost dependent upon each other. He could not tolerate the knowledge that he needed another person. He was still George Maharis, who wanted and needed no one. And he was going to stay that way.

He hadn’t been cursed

The next big change in his life came the year before he graduated. He joined the Marines. And there he made a friend—or rather, someone else made a buddy of him. And in the close-knit group of men, forced by barracks life to live together in harmony, George could find no way to shake loose the warm-hearted guy who was determined to like him and to share his inner life. Grudgingly, he gave in a little.

And then the least predictable event of all occurred. George was transferred to a camp in the deep South. There for the first time, he found himself surrounded by a poverty that made his childhood seem like luxury. This was poverty that afflicted whole towns, whole generations in a row. Gradually, he came to understand that he had not been singled out, that he had not been uniquely cursed. He realized there were many, many others who suffered his fate and an even worse fate. He realized, too, that his parents were not to blame for what had happened to him—they had done their best in a situation which had defeated many. They, too, had not been alone.

He spent a good deal of his remaining time in the Marines pondering these things. He reached a number of important conclusions.

“I know now,” he said, “that there was a lot of love in my life when I was a kid—only I couldn’t see it. And when I did, I ran away from it. I guess I expected love to be all soft words and caresses. For some people in some worlds it is. But now I know love can be many things. Sometimes love can be a hit on the head—like when my mother fired that plate at me, trying to straighten me out. Love can be taking someone else’s beating for him, the way my brother did. Love can be a punishment or a refusal or almost anything—if you just have the eyes to see it. Love was pretty heavily disguised in the world I lived in, and my eyes weren’t good enough. But when I came out of the Marines. I decided I was going to try to see straighter.”

He went home from the Marines, and for the first time in his life, threw his arms around his mother and kissed her warmly. Holding her in his arms, he made the bravest decision of his life: he would try to break down the wall of isolation and defiance he had hidden behind for so long. He had learned to live with other people on the surface—now he would open his inner life and learn to love.

That was a number of years ago. Today George Maharis wonders if he made up his mind too late.

It is true that George has friends now, and fame and money. It is true that he no longer consciously rejects the girls he meets and dates—indeed, he sometimes almost succeeds in taking the last necessary step—entrusting his heart and his happiness to a girl he can marry.

But it is equally true that much of his nature still fights—successfully—against these goals. The little boy he once was keeps him living today in a tiny thirty-five-dollars-a-month slum apartment to which he could never bring a date. That little boy, still wary of attachments, still forces him to give away any piece of clothing, any souvenir, of which he becomes too fond. That little boy still arranges his life so that he is cut off from the world whenever he is not working. He gets up at three in the morning to indulge the solitary hobby of painting, or to walk the streets of the city, dressed so casually that police have mistaken him for a vagrant.

George realizes these things, and they terrify him.

“All that I learned about love—what good will it do me if I found it out too late? If now that I want to love, I can’t? I’m still young, but sometimes I feel as if life is going by so fast—and I know the longer I wait, the more set in my ways I’ll become, the harder it’ll be to make changes. And I’ll have to change if I’m going to marry and have the family I want. I’ll have to change—but how can I? Sometimes I think, if I could just find a girl who’d let me be alone when I need to—then maybe . . .

“But then I ask myself, what kind of a relationship would that be? Is it possible I’m just not able to give up enough of my independence—after all those years of having nothing else—to make a good, lasting relationship with a woman? Maybe it is. And man, that scares me. It’s not so bad now, while I’m young and having fun—but what about when I’m fifty and girls don’t find me so attractive and the big show is over? What’ll I have then? What’ll I have to leave behind someday instead of the family and the memories I’d like to leave—a big bank account?

“Look at this apartment of mine. I’m proud of it. When I first rented it I got it extra cheap because the last tenant had been lying dead in it for nine days before they found him, and the place stank. I had to wash it down and scrub it out with disinfectant. When even that didn’t get the smell out, I tore down the walls and put up new ones myself, with my own hands. Now I live here even though I could afford something better. I keep telling myself it’s because I don’t want to get tied down to some big fancy place I’d have to sell my soul to run, the way some actors do. But every now and then I have to ask myself, do I really hang onto it because I know I fixed it up all by myself—with no help from anyone, with not a touch of anyone else in it? See, it’s that the-rest-of-the-world-be-damned feeling coming back. I fight it, sure I fight it. But I’ll tell you one thing—right now, I don’t know who’s gonna win!”

THE END

—BY CHARLOTTE DINTER

Be sure to see George on “Route 66” on CBS-TV every Friday at 8:30 P.M. EDT.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1961

zoritoler imol

3 Ağustos 2023I love your writing style truly enjoying this internet site.