Wanda Hendrix: “I Can Love Again”

She had probably never said it before to anyone, but she said it right out, without prompting or probing. “I’m not in love. Not anymore. But I want to be. I will be. I can be—now.”

Very tiny, elfin, like an animated piece of Dresden, Wanda Hendrix sat across from your MODERN SCREEN reporter and said for the record that the last flicker of her love for Audie Murphy had died. If there was any emotion in her voice it was one of simple regret. Her manner was candid, and there was no roar of tumbling bulwarks as the admission was made that a marriage which had captured the romantic imagination of the world had failed, and that the institution has suffered.

Yes, the institution of marriage has suffered, because when a lovely young actress marries a boy who might well go down in American history as the greatest warrior of them all, we steep ourselves in the beauty of their love. When their dreams are revealed as clay, so are ours by reflection; and when their marriage words prove as sacred as evidence in a traffic court, a bit of our world crumbles.

A report is in order. The. prelude to Wanda’s love, which was secret in the time of its existence, must be played again and viewed in retrospect, for we are all interested parties.

A question to Miss Hendrix: “When did you first love Audie Murphy?

Her answer: “I don’t know. I can’t be sure now. Maybe the first time I saw him.”

A question: “And when did you lose him?”

Her answer: “The moment I married him, That very moment. I heard the words ‘I now pronounce you man and wife,’ and I turned to kiss Audie and he wasn’t there. A man who looked like him stood before me, but Audie wasn’t there. He’d run away while I stood by his side—and he never came back.”

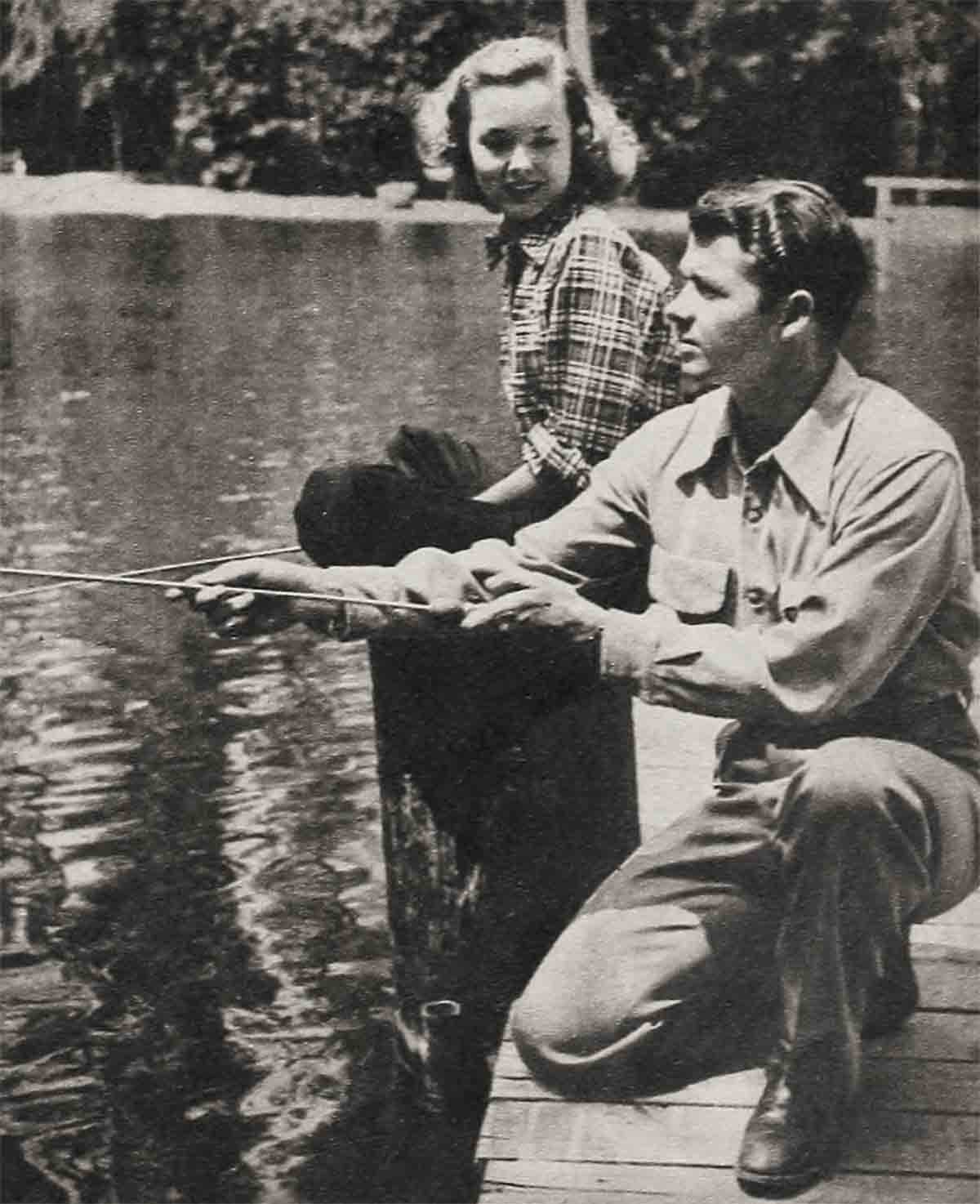

We have evidence to disprove that, of course. Some of us were there, and we have photographs of Audie Murphy and Wanda Hendrix, smiling and blissful, waving gaily as they stepped into their car to drive away on their secret honeymoon.

A question to Miss Hendrix: “But what of your honeymoon?”

Her answer: “There was no honeymoon. You must remember that Audie ran away during the ceremony.”

Subtle? Well, rather. Unusual? Not at all. It happens every day. It happens everywhere. And because it is commonplace it can be spoken of freely, and analyzed openly. After two years Wanda Hendrix knows this and will speak of it.

“I was very much in love with Audie,” she said. “I was seventeen. Even though I was an actress I didn’t know very much, particularly about boys. Somebody said he wanted to meet me and it was arranged. Maybe you don’t think he is handsome. But I did. He wasn’t very tall, but he held himself straight. His hair was red—and I immediately liked red hair. He seemed thin, but I decided right then that I liked a man thin. His features were delicate, which surprised me, because I had heard that he was the fiercest soldier in the war. And his mouth was full, and looked generous and kind. His eyes were soft, and all about him there was the shyness of a little boy. I wanted to touch him, but I was afraid it would frighten him.”

Living, for the moment, four years back into her life, Wanda Hendrix was nervously animated by her memories.

“I wasn’t very pretty,” she said. “At least I didn’t think I was. And this wonderful boy seemed to like me. At first he was very reserved. He would call me on the phone and hardly talk—just ask me if he could see me, or if we could have dinner together or go to a show. As time went on I began to feel very close to him, and there was a restlessness in me. I thought he was never going to kiss me—and I wanted him to.

“Then one night he looked at me differently. His eyes weren’t clouded with respect. They weren’t shy. They looked at me directly—all of me. They frightened me a little, but in a moment they sparkled with devilment. Then he kissed me, and I thought I’d always been in love with him.

“After that,” said Wanda, “we were together all the time. Murphy was going to school, studying to be an actor, and I was working at Paramount. Whenever we could we’d meet during the day, and at night we’d be alone together always, generally in some quiet place. We talked a lot, about everything, but mostly about Murphy. He didn’t talk much about the war, just once in a while, but he told me all about his childhood and boyhood and all the things he thought about.”

Wanda folded her hands on the table top, almost as if she were clasping a handful of dreams that she wanted to examine once again, and she stared at her hands to see the dreams better—and make sure she wasn’t mistaken about them.

“If I had been smarter,” she said, “maybe I could have seen that Audie wasn’t ready for marriage—at least not to me. He told me that his father had died when he was a baby, that he was separated from his brothers and sisters, and that all he could remember was the will to have enough to eat and enough to wear—and that he had never been loved, except by his mother. She died when he was sixteen, and he went off to war. If I had been smarter, I would have known that there hadn’t been enough living in his life, or enough love, to make him ready for marriage to me.

“I never knew Audie after we were married,” Wanda said sadly. “When I turned to kiss him, he was gone. The man who stood in his place, where he had been standing a moment before, was a stranger, and when I kissed his lips he didn’t kiss me back. I was different, too. We stood hand in hand, we strangers, and posed for photographers, and then we went away together, and we didn’t speak. When it became necessary, we spoke only of un-important things, miserable details, not at all like lovers.”

A psychologist could explain it more elaborately, but the simple fact is that when Wanda Hendrix turned to her groom he wasn’t there. He had run away. Audie Murphy, the greatest hero of history, had run away. And the sad part of the entire tragedy is that he couldn’t help himself—nor could his wife help him.

“We were respectable people with a high regard for marriage,” Wanda said, “and we tried to adjust ourselves to it. Maybe because of the fact that we were well known to the world, and because we felt, we owed it to the people who had placed such faith in our marriage, we tried harder than most couples would have. And it was harder than most. It seemed that every time we picked up a paper a quarrel or a kiss that actually belonged only to us was featured. When we separated, we were both censured, and when we reconciled, we were both publicly presented with the responsibility of not letting a separation take place again. And then—it seemed so fast, although it must have taken a long time—it was all over. And I was very unhappy for a year—I’m sure Murphy was, too.”

This writer’s conclusion as to what happened to Audie Murphy is based on scientific fact, laboratory tested and proven to the exact science of psychiatry.

In a magazine article printed during the early part of his marriage to Wanda Hendrix, Audie Murphy was quoted as saying that he objected to writers labelling him a “psycho,” the G.I. term for an emotionally maladjusted person. He had a right to object. The word, as it is loosely used, has an unsavory connotation. During the war, it meant, popularly, a person who was so filled with the dread of battle that he was inefficient in combat—and in some circles it meant coward. In that sense it is a laughable term to apply to Audie Murphy.

However, spreading the word to its full stretch, psychopath, it becomes not at all unkind and, even though not fitting, remotely explanatory of a condition that inhibits all men. There are few men or women alive who are without some emotional instability. There are none with Audie Murphy’s background.

There is an exact psychiatric formula that can trace the road Audie Murphy took when he fled from Wanda, his wife, but it would take a psychiatrist to explain it and another to understand it. But Wanda Hendrix. Murphy, a good woman who wanted to be a good wife, searched for the answer, for she felt she had been remiss—and she found it. It agrees with the accepted beliefs of the psychologists, and is presented here without quotation marks, for Wanda’s path is traced with it.

Take a boy, born in the big, sprawling, rich and rowdy state of Texas, where a youngster must be a man from the day he first tilts his big hat over his young eyes and spits into the dust belligerently. A state where a name, used as often as “if” in the north, means a fight, even with a man’s best friend. A state where pitiful poverty squats in the very shadow of fabulous wealth: Take a particularly sensitive boy, who, by circumstances, is born listed in the gutter registry. Take his desire for love and confuse it by spreading it thin among a lot of people he’s not sure he has the right to love then leave him only one human being to fix his love on like a small target, his mother. Let him know that only one human being, his mother, has the duty and the free unpartisan will to love him, and maladjustment forms like a boil.

Take his mother away forever at sixteen, when he is neither a boy nor a man, when the gateway to his life has just swung wide, when the crust of security has not yet hardened and his fears, hates, prejudices, and ambitions are in a molten state of flux. He’ll explode or carry the hidden boil to his death, unless he has it medically, yes, medically, removed.

Audie Murphy’s behavior in the war was a direct result of his childhood, and the addition of other emotional shocks suffered in combat. His patriotism and bravery is beyond question. Privately, however, in conversation and in his own book, To Hell and Back, he admits the growth of the compulsion to destroy without passion all evil in his path, and a complete and unnatural willingness, that was almost a desire, to die in the process.

It is to be gathered from reading To Hell and Back that the end of the war left little hope in Murphy’s heart. Could it have been because his lover, Battle, had left him and died, too? Could it have been that in Battle he found something of the security he felt when he had his mother, a reason for existing, a reason, even, for ceasing to exist? At any rate, poverty, a single fixed love, and Battle had been his life—and he was at a stage in his emotional life when he might have rejected anything or anyone else.

That was when Audie Murphy met Wanda Hendrix.

Wanda Hendrix was a poor girl from a large family in the incredibly socially unbalanced state of Florida. Loved and protected and guided intelligently from her earliest childhood, she moved toward maturity on an even keel, emotionally stable and unaware, actually, of any “difference” between herself and her “betters.” She was without frustrations, at least pain-inflicting frustrations. Her goal was a career as an actress, and, because she was talented, lucky, and plucky she travelled toward it with such ease that at seventeen she was riding the crest of a comber headed for the big beach. Her normal appetites to love and be loved were well satisfied—and her appetite for a man of her own was normally keen. She was ready and able for marriage.

That was when Wanda Hendrix met Audie Murphy.

The idolators, you and I, didn’t know their backgrounds. All we saw was a boy and a girl of a proper age for one another, uncommonly attractive, both headed for individual successes—and, according to the gossip, very much in love. We took nothing else into consideration. And when they failed us, we took nothing else but the simple, current facts into our thinking in making our judgment. Somebody must have been at fault, we thought. He must have been a brute to her, or she was an inadequate wife. At any rate, we thought, they’re both young, they should forgive one another and start over again.

It is the contention of qualified medical authorities, presented with their problem by your reporter, that they should have both seen-a psychiatric counselor, and that if they had, they would probably be together today.

”I wanted Audie to see a doctor,” Wanda said. “Not that there was the slightest idea in my mind that there was anything terribly wrong with him, but I knew something in his emotional make-up made him reject me. And that such a rejection, after all we had been to each other, must have been based on something that had taken place before—maybe in his childhood maybe in the war. If we only had . . .”

However, in Hollywood, as in other communities, there is a prejudice against this very simple procedure. Even in this city, with an intellectual behind every bush, there is the inclination to establish the patient of the psychiatrist as a loony who at any moment might strip naked and do a Spring dance in the middle of the street, or pull a knife on his best friend. So Audie Murphy and Wanda Hendrix, instead, went to see a couple of lawyers, and they both suffered through a divorce that neither actually wanted.

A question to Miss Hendrix: “And now is your life ruined? Do you fear marriage?”

Her answer: She laughs, “Certainly not! I’m only twenty-one. I’m sorry I made a mistake, but I believe in marriage. I want to marry again, maybe to an older man. Somebody as ready for me as I am for him. I don’t even know what he looks like yet, but he’ll come along one day and I’ll know him. I can love again.”

Wanda seemed relieved that she had said it and relieved that she meant it. She was brimming with good humor and smiles as she picked up her bag and excused herself to keep an appointment. She walked off, toward the door, and she stood aside as a tall young man smoking a pipe held it open for her. She looked into his face, maybe to see if he was the one—but if he weren’t, there would be one, sometime, somewhere on the other side of the door.

THE END

—BY JIM HENAGHAN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1951

No Comments