The Wasted Years—Olivia de Havilland

Now that Olivia de Havilland is divorced and the wasted years are over, the truth of those years of suffering and fear in which she lived with Marcus Aurelius Goodrich may be told.

It is not a pretty story.

Other than for momentary flights into pleasure and passion, it is rot even a romantic one, but implicit in it is a lesson which every young woman should learn.

The lesson is this: To marry a man without really knowing or understanding his personality is to court almost inevitable marital disaster.

Six years ago Olivia de Havilland was married to the novelist, Marcus Goodrich. Months later she learned, according to intimates, that she was Goodrich’s fifth wife. Olivia is reported to have told a friend, “I didn’t find out how many times Marcus had been married until I read it in the newspapers. I knew practically nothing about his previous marital history.”

Coming from Olivia de Havilland, such a confession is surprising, for here at 36, is one of the most intelligent, perceptive, and brilliant actresses in Hollywood history.

Here is a young woman who has won two Academy Awards and never given a bad screen performance in her life. Here is a young woman of shrewd judgment who has chosen her own scripts, The Snakepit, To Each His Own, The Heiress, My Cousin Rachel and upped her salary to $175,000 per picture.

Now, how does such a knowledgeable, perspicacious, independent, and wealthy young actress get married to a man of whom she knows so little? A man who, it is alleged, sought no employment, let his wife become the family breadwinner, on occasion beat her, caused her great mental suffering, threatened her with physical harm, and turned her into a nervous wreck?

If that language sounds too strong to you, it is nothing compared to Olivia de Havilland’s testimony in court. Listen to her as she tells the judge what life with her ex-husband was like from August 26th, 1946, when she married him in Weston, Connecticut, to May 8th, 1952, when she finally left him:

“We were driving in a car—my husband was at the wheel—along Sunset Boulevard, in the area of Bel-Air, and having some sort of normal conversation. Mr. Goodrich took exception to something that I had said, something that was so trivial I cannot remember it, and began to pound my left arm with his closed fist, and this continued for several minutes, and when we arrived at our home which was in Bel-Air, I got out of the car and he had said that he would kill me. . .

“I got out of the car and ran down the driveway and down to the road that runs along the outside of the property where we were living, and I believe I sat down on a rock in some shrubbery and I didn’t know where to go or what to do.

“After a while my husband found me there, he came to hunt for me, and I told him I was afraid to get in the car because he had said he would kill me.”

As a result of the arm-pounding, Olivia told the Court, “I received a very large bruise which was dark blue and purple. The bruise . . . on my left arm between the shoulder and elbow, was about the size of a baseball.”

In order to conceal that injury from her Hollywood friends, Olivia said, “I just used colored scarves. It was warm weather and I was wearing short-sleeve dresses, and I used scarves which I tied around the arm to conceal the bruise. It was very humiliating.”

From 1946 to 1951 Olivia de Havilland maintained the fiction that her marriage to Marcus Goodrich was one of those divine couplings ordained in heaven, an incomparably happy union she never wished dissolved. When a baby boy, Benjamin, was born to her in 1951, she told reporters that she was the happiest woman in the world, that now her marriage was truly complete, truly ecstatic.

I and others who had seen her in company with Goodrich knew that she was whistling in the dark, trying to keep up her courage, hoping against hope that her husband might change. A consummate actress, Livvy felt at the time that she was actually fooling all her friends. She wasn’t; we knew the score. We knew she was miserable, cowed, completely dominated by Marcus, living in almost perpetual fear of the man.

It took six long years, but Olivia finally told the truth about herself, her baby, and her husband; and she told it in court.

“During the first five-and-a-half weeks of the baby’s life,” she testified, “I took care of him all by myself—I wanted to take care of him all by myself and I did. During that period of time, well, the baby was four weeks old and I was caring for him in the bedroom of the house and my husband became upset for something—I cannot recall what it was—it was unimportant—and he became extremely violent and abusive in his manner and he struck me . . . I had to turn my body so that the baby would not be injured because I was holding Benjamin in my arms at the time.”

One more extract from the Court record and you’ll have some idea of what Olivia de Havilland put up with rather than admit marital failure.

The following extract deals with Christmas, 1951, when the actress was on the road, touring in a stage play, and stopping over at the Hotel Utah in Salt Lake City.

Q: Do you recall the occasion that a person came tothe door of the hotel suite and asked for your autograph?

A: I do remember that.

Q: Will you briefly tell the Court just what happened and what he (your husband) said on that occasion?

A: Yes. Someone came to the, door and asked for my signature and my husband was rather angered by this request and became rather excited and quite impatient and unkind.

Q: Was it a repetition of similar moods that you have described?

A: Yes, it was.

Q: How did that affect you?

A: I was disturbed for two reasons: I did not like to see such a small incident upset my husband, and I wanted to avoid a repetition of this kind of thing in the future because these rages disturbed me very greatly.

Q: What did he say particularly on that occasion that affected you? What was the threat that he made?

A: I suggested to my husband that next time if anybody came requesting my signature that Nellie, the wardrobe mistress, who is also my dresser—I suggested that he let her handle the situation as she was accustomed to doing so. She had always handled situations of that kind through all the years she had been in the theatre which were at least 20.

Q: In her presence what did he say?

A: He turned to me and said, “I will beat you for that,” and started to cross the room.

Q: How did that affect you?

A: I was deeply upset, not only by the threat, but also by the fact he had said that in front of a third person. I felt the fact he had forgotten himself in front of a third person was a very dangerous thing and the next time I was alone and he became angry, I thought I might not survive.

Why should a woman, particularly a talented actress who supports her family, put up with such treatment for six years?

This is the question all her friends have asked Livvy.

Why didn’t she pull out as soon as she learned what sort of husband Marcus Goodrich really was? Why wait around for the punishment?

Her answer is characteristically simple, “It couldn’t bear the idea of divorce. I didn’t believe in it. It was my only marriage and I wanted it to last. Before I decided on divorce, I consulted my minister and asked his advice. It was only when I realized that my son was in danger, both physically and psychologically, that I had to face the fact that the marriage simply could not continue.

“I was faced with two alternatives-neither one was desirable. One was divorce and the other was a home in which my son might be done great physical and psychological damage, I decided after I talked to my minister, the only thing to do was to get a divorce.”

Olivia got her divorce last year. It was uncontested, and she waived alimony, attorney’s fees and court costs. She paid for everything and was awarded custody of her child with the right of reasonable visitation going to Goodrich if he desires to exercise it.

Since August of 1952 and her divorce, Olivia de Havilland has become a new woman. No longer is she the frightened, bewildered, dominated young wife who each time looked at her husband with trepidation before she answered a reporter’s questions.

Today she is an attractive, vivacious, bubbling, spirited woman full of warmth, energy and drive, and she is beginning once again to go out with men.

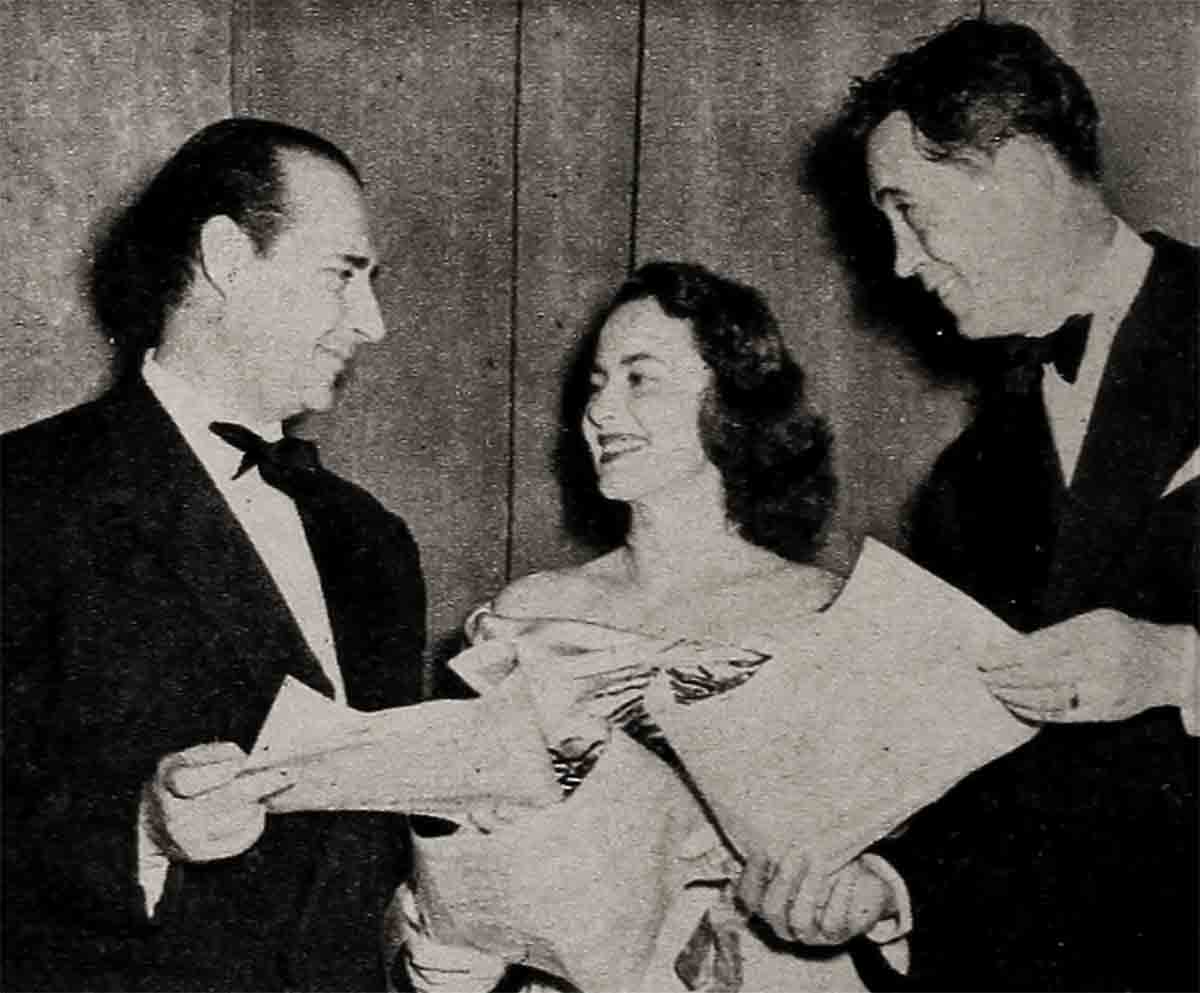

John Huston and Olivia met for the first time in years when he arrived in Hollywood during Christmas Week last year to show his Moulin Reuge for Academy Award contention. It was a romantic and sentimental reunion, for when Olivia was a young actress on the Warner lot during the late 1930’s, the first man she genuinely fell in love with was the lanky, quixotic Huston. They went together for years, and there was much talk of an impending marriage, but these two were almost similar in temperament and viewpoint, and the love affair eventually faded.

What memories were aroused early this year when Olivia and Huston ran into each other at several of Hollywood’s New Year parties, I don’t know. Huston has re-married for the third time and is no longer free, but I do know that when they met at the Vincente Minnelli party, Olivia looked more ripe, more beautiful, more radiant than she ever has before.

Olivia de Havilland first saw her husband at a dinner party five years before she married him. The dinner was held at the home of Arthur Hornblow, the MGM producer, and Goodrich, who speaks beautifully, was waxing eloquent on the various virtues and faults of women in America. All that Olivia remembers of the affair, and this rather hazily, was that Goodrich said he thought he’d go to Scandinavia, marry a healthy young girl and have a dozen children, whereupon Olivia said, “Why go to Scandinavia?”

She wasn’t impressed by Goodrich, merely regarded him as a pleasant fellow who’d obviously been around.

At that time, which was 1940, Livvy was actually thinking more of her career than of her love-life. She was exceedingly ambitious, and that’s putting it mildly. She’d finished the role of Melanie in Gone With The Wind in which picture she had established herself as a sensitive, perceptive actress.

By 1946, however, after 11 hectic years of career obsession, and a tearful farewell to John Huston, Olivia had seen through the illusion of Hollywood, and she was more than ready for a personable and presentable man. She had worked in many films, and tiring of them temporarily, agreed to go to Westport, Connecticut, to do a play.

In the Spring of 1946, Olivia boarded the train for New York on a mission with a one of her best Hollywood friends, Phyllis Seaton. En route to the East, both girls began to plunge into various subjects, the most fascinating of which turned out to be something called, “Men.”

Phyllis brought up the name of Marcus Goodrich as an eligible man-about-town and Olivia said she had met him five years ago.

“That’s a coincidence,” Mrs. Seaton said, “Mareus is an old family friend and he’ll probably phone us in New York.”

That’s exactly what happened. A day after Phyllis and Livvy checked into their hotel suite, Marcus Goodrich was on the phone. That night he took both girls to dinner. Two nights later, he asked for the same privilege. Again it was granted. On Friday night he phoned for a third date, and on this occasion Phyllis Seaton, very happily married, took the hint.

“I’ve got a nasty headache,” she told Livvy. “You’ll just have to dine with Marcus alone.”

He and Olivia talked until three the next morning, and Goodrich, glib and mellifluous, was absolutely fascinating. At least, Livvy thought so.

A day later she had him drive her from Westport to East Hampton on Long Island. During this trip Marcus asked for all her biographical details, and as Livvy recalls, “We became so entranced by the subject that we got ourselves lost five times.”

By the end of the trip, Marcus was ready with a little advice for the talented actress. He had heard his date out and he was convinced, so he said, that she should remain single for another two years and then get married—not to a writer or an artist, but to a successful business man. Olivia said this made good sense and she would in all probability follow Marcus Aurelius’ advice.

Less than a week later, Goodrich was back at Olivia’s hotel. Over luncheon he said, “Will you marry me?”

Olivia’s eyes sparkled. “But you’re not a successful businessman,” she cracked. Then she said yes.

They talked until the early hours of the morning, Marcus explaining to his bride-to-be that “you are the type of woman who has enormous respect for duly constituted authority. One of the needs of your nature, like that of every real woman, is to be able to rely upon your mate.” Olivia fell for that routine hook, line, and sinker.

When Goodrich discussed the wedding ceremony with her, he reportedly said, “I’d like very much if in the ceremony you would promise to obey.”

Olivia knew that contemporary marriage ceremonies carry the promise to “love, honor, and cherish,” that the word “obey” is considered out-moded in the light of woman’s modern accomplishments, and she should have gathered, from his insistence upon this point, some idea of Goodrich’s dogmatism, but she hardly gave it a second thought.

Once back in Hollywood, he began to manage his wife’s career which, up to this point, had been brilliantly directed. In the process he antagonized agents, reporters, executives, dozens of persons who had known, loved and long respected Olivia.

Some of these friends began to refer to Goodrich as “Svengali,” so completely did he come to dominate this actress who had once been too strong to be dominated by anything except her own unbridled ambition.

As Olivia de Havilland’s husband, Marcus Goodrich was no success in Hollywood. People began making cracks about the fact that Olivia was the family breadwinner, that outside of writing one novel, “Delilah,” Goodrich didn’t appear to be very productive. Gradually, some of the more sensitive souls in Hollywood began to drop the couple socially.

Many of us knew Olivia was unhappy, but few of us realized that life with Goodrich had deteriorated into the miserable shambles she later described in court. Few of us imagined that Marcus would ever dare use physical force on so fragile and high-strung a woman. We knew the writer was opinionated, strong-willed, and frustrated, but we figured that once his wife became pregnant, he would alter his ways and become a kind and considerate husband; apparently, this didn’t happen.

“I was confined to bed for seven months during the time I was expecting my son,” Livvy has explained, “and I wasn’t allowed to get up because of the danger of losing the baby. It was our custom to dine in the bedroom—my husband would have his dinner at a card table and I would have my tray in bed. One evening my husband was served beefsteak pie . . . and he was very upset because it was not steak and kidney pie and he threw the pie across the room and left the house.”

After the baby came and Marcus still refused to mend his ways, Olivia went to see her minister and together they decided that divorce was the only solution.

Last June, Olivia returned to Hollywood with her little Benjie. and gave out the announcement that she was going to divorce Marcus Goodrich and play the lead in My Cousin Rachel.

Hollywood was happy for her on both counts.

When deHavilland works she throws herself into a role with such complete concentration that at the end of the day she’s exhausted and has no time for the social amenities. It was that way with Livvy during the making of Rachel. She was rarely seen around town.

Once the picture was finished, however, we saw a new Livvy emerge, a girl of warmth, vibrancy, and tenderness. To begin with, Olivia reconciled with her father, from whom she had long been estranged. Various reasons have been attributed to this estrangement, but the truth involves the story of the de Havilland family background heretofore untold.

Olivia’s father, Walter de Havilland, left England in 1893, after graduating from Cambridge, to head a law office in Tokyo. In 1914 he returned to Britain where he met a young lady named Lillian Ruse who was studying drama in Sir Beerbohm Tree’s Dramatic Academy. Young de Havilland, an impetuous bon vivant, proposed marriage and asked the girl to return to Tokyo with him.

Lillian Ruse said she wasn’t sure. “Tell you what we’ll do,” Walter de Havilland suggested. “We’ll toss a coin. Heads you go to Tokyo as my wife. Tails you stay here single.” The coin was flipped. It came down tails, but Lillian Ruse changed her mind. She decided to marry the young man anyway. Two years later, a daughter was born to the couple in Tokyo on July 1st, 1916. This first-born daughter was christened Olivia. A year later another daughter was born. This one was christened Joan de Beauvoir de Havilland.

Unfortunately, life in Japan didn’t agree with the babies, so Mrs. de Havilland, not too pleased with her marriage in any case, packed their things and sailed with them to California. On arriving, she made a home for her girls in the small- town of Saratoga.

In 1925, Mrs. de Havilland decided to divorce her husband and returned to Tokyo for that purpose, leaving her daughters with a nurse. When she returned to the States a few months later, she discovered happily enough that Joan and Livvy had made a fast friend of a department storeowner, a French Canadian, named George Fontaine. Mrs. de Havilland also became his friend and subsequently his wife which is how Joan de Beauvoir de Havilland came to take the name, Joan Fontaine.

Not long after Mrs. de Havilland became Mrs. George Fontaine, her ex-husband decided to marry his Japanese housekeeper. Joan saw nothing scandalous in this. In fact when she was 15 she went to Tokyo to live with him and his Japanese wife for two years. Olivia, however, viewed the entire affair with jaundiced eye and declined to see her father.

When at 69 Mr. de Havilland arrived in California with his Oriental wife, World War II had begun, and his wife was ordered out of the West Coast war zone by War Department authorities. The couple went first to Denver, Colorado, where they eked out a bare living and later to British Columbia in Canada where they now reside.

Olivia hadn’t seen her father for years when, after finishing Rachel, she decided there was no point in perpetuating this paternal estrangement. She called Walter de Havilland long distance and told him that he must come to California and see his new grandchild, Benjamin. She paid all the travel expenses, but her Japanese step-mother did not accompany her husband. She remained in Canada.

When the old man arrived at Union Station in Los Angeles, Olivia and her little boy were on hand to meet him. Tears of joy punctuated the reunion, and one got the feeling that one of Walter de Havilland’s fondest dreams was coming true.

Olivia has also reconciled with sister Joan. Before they were married the two actresses shared a cottage in Coldwater Canyon, and there was no talk of jealousy and feud concerning them. After Joan became Mrs. Brian Aherne, however, the girls separated, and there was much gossip to the effect that Aherne had been Livvy’s beau to begin with and that Joan had stolen him away. It was all stuff and nonsense. The two actresses simply began to grow apart, to lead different lives.

Olivia’s only husband, Marcus Goodrich, had no liking for Bill Dozier, Joan’s second husband, so that no attempt at reconciliation was made during his six-year regime. If anything, salt was thrown upon the open wound.

Once Joan divorced Dozier, however, and married Collier Young a few months ago, she ran into Livvy at the Beverly Hills Hotel and invited her sister and her nephew to visit her family. Livvy said they’d be glad to come, and that was that.

From here on in, Olivia de Havilland is determined to be kind, friendly, and at ease with everyone. She has no room in her heart for bitterness, rancor, or feud of any sort. She had quite enough of that in six years of marriage—years which she insists were not wasted, “because really I learned a good deal-from them.”

The most important thing Livvy learned, and it cost her a fortune in money and heartache, was something every girl should be told by her mother: Marry in haste and the chances are very good you’ll live to regret it.

THE END

—BY WILLIAM BARBOUR

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1953