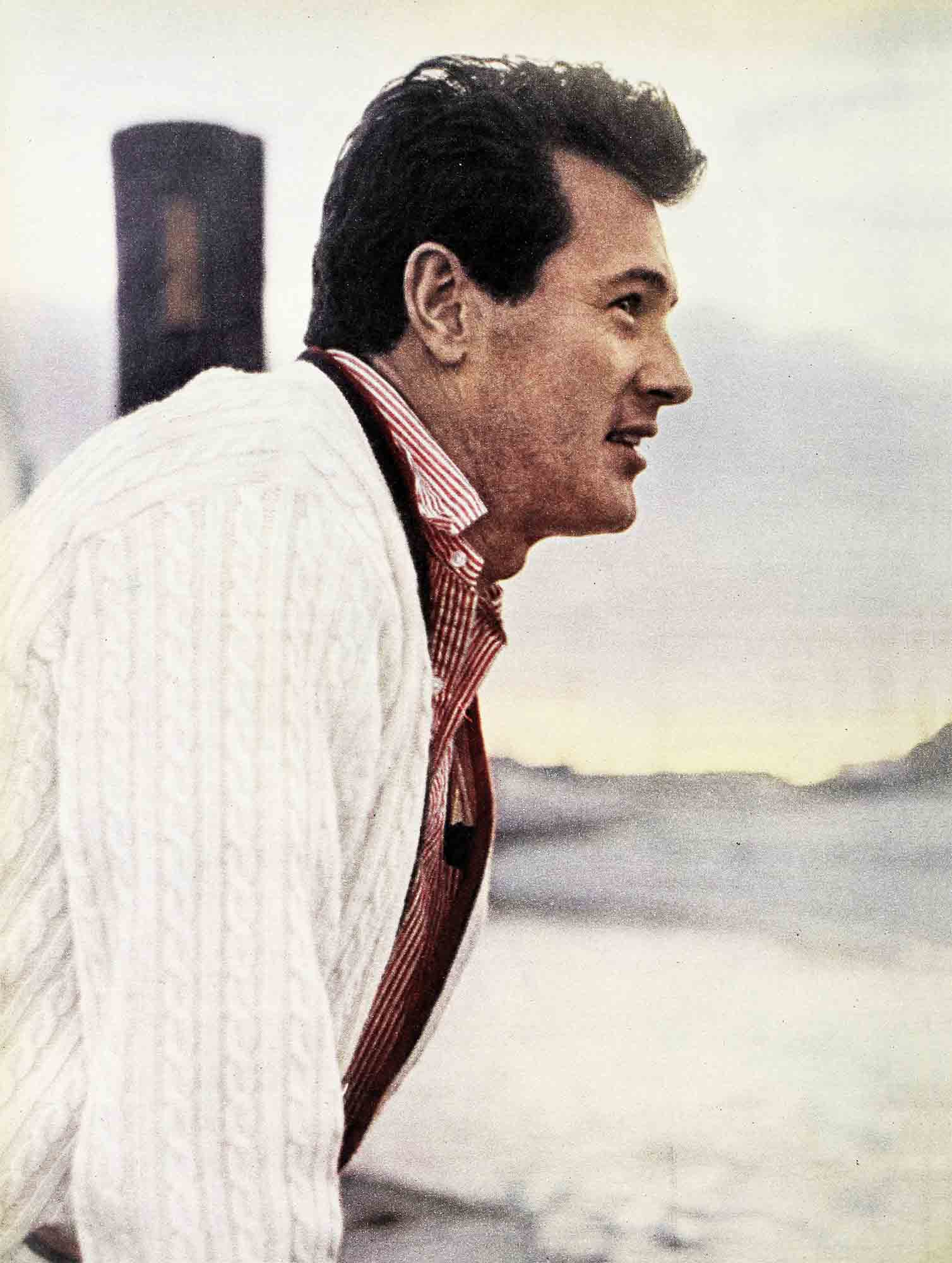

Rock Hudson: “I Was Scheduled To Die”

Some things we have no way of knowing about; no way to predict their happening; no way to stall off their beckonings. They come upon us and most times we’re ill-prepared to meet them. After they happen, we wonder: “If I’d put two and two together. . . ?” But we never do, do we? Looking across the blue-emerald green Mediterranean water, Rock Hudson probably, even if he stopped his thoughts, could never have predicted what was to await him later that same day. If he had, you can be sure he would never have left shore.

Rock stood at the edge of the water, shoulders slouched, hands dug deep into the pockets of his khaki pants, squinting into the glare that reflected off the Mediterranean. The water was so blue and calm.

AUDIO BOOK

“An uneventful day for sailors,” he thought, “but a perfect one for sightseeing.” He felt as excited as a kid at the prospect of the trip down the coast through the Lerin Islands. He’d heard so much about them that when Mrs. Barclay, wife of his friend Eddie Barclay, the composer and orchestra leader, had offered to show them to him, he’d said yes immediately.

He’d left the hotel early that morning to make the most of his few days in Cannes and now found he had almost an hour before meeting Mrs. Barclay at the boathouse where the Hello was moored. He walked along the beach until he found a deserted spot and stretched out on the sand. “Better relax while I can,” he thought. That night, he had to leave for Portofino to start the movie, “Come September.”

“The Mediterranean’s a long way from Lake Michigan,” he laughed to himself. As a kid, he used to spend summers at Lake Michigan, at his aunt’s place. He’d learned to swim there. Nobody thought he’d turn out to be such a good swimmer. He above all; he felt he was too tall and too clumsy to ever be good at anything.

It was funny. He had dreams of drowning. He couldn’t remember if they’d begun after the accident, the one where he’d been surfboarding and had broken his shoulder. For a while, he had been afraid he might lose his first big role, in “Magnificent Obsession,” because of it, but he made the doctors strap him up and somehow he got through the filming. “Funny,” he thought, “that I should remember that today.”

He shrugged his shoulders and sat up noticing, for the first time the little boy who was crouched down on the sand watching him.

Hoping he remembered the difference between the words for morning and night in French, he called: “Bonjour.” The boy quickly turned away, pretending to look at the water, and dug his toes deeper into the sand, but he couldn’t resist looking back.

Somehow, mostly through sign language, he found out that the boy’s father was a sailor and was on a trip. They were friends by the time the boy’s mother came looking for him. She had to call three times before the child answered, and as he walked slowly toward her, he kept turning around every few yards to wave goodbye again.

Rock understood how lonely the boy was. It was hard to have someone go away and leave you.

He had been only six when his father had left them. When he returned home from a visit to his grandparents’ farm and found his father gone, he couldn’t understand why he would go away without even saying goodbye to him. They had always done lots of things together and whenever he visited his dad at his garage, he’d try to stop working for a while and talk to him. And, at night, they’d play ball behind the house until it was too dark to see.

“Someday you’ll be a baseball player, Son,” his father would say. But it his mother were listening, she’d say: “My son is going to be a surgeon,” and sometimes they’d argue about it. But they hardly ever got mad.

He could only remember one time when his father hit him. That was the morning he didn’t want him to go to work and he stood in the doorway blocking the way. Finally his dad got mad and hit him. But later in the day, when he came home for lunch, he d forgotten all about it and had brought him a burned-out spark plug for his collection.

That’s why he couldn’t believe his father had really gone, and mornings he’d come down to breakfast expecting to see him there. His mother couldn’t believe it, either. She used to say over and over to her mother: “Roy will come back to me. He’ll come back to me. I know he will.”

But he never did, even though the next year his mother took him all the way out to Los Angeles where his father was working. His dad was very nice to them, but a couple of days later, when they took the bus back to Winnetka, he didn’t come with them.

Although no one ever said it out loud, he got the feeling that if only he’d been home his father would never have gone away, that he cared too much for him to have ever left him. It was his fault that it had happened, he told himself. He was responsible for his mother’s unhappiness. She was so beautiful and used to be so gay that he wished he could help her. He wanted to talk to his father about it but he didn’t see him again for a long time.

One day, when he was twelve, the doorbell rang and he answered it. A man was standing there. He didn’t recognize him, but answered politely when he said: “Hi, kid. How are you? I’ve . . . been wanting . . . to . . .”

A shout from his mother interrupted him and he was sent upstairs to his room. He didn’t find out until a long time later that it had been his father, and that he was told not to bother him again. He never did. Years later, Rock looked him up in California and lived with him for a while, but it was too late—he was grown up then.

Rock now looked up. The wind had suddenly shifted and blew up a light cloud of sand. With a practiced navigator’s eye, he looked at the sun and judged it was time to leave. He kicked off his sneakers and started, barefooted, toward the boat.

He knew there were people who said he decided on the spur of the moment to try for the movies just because he was good- looking. “It isn’t true,” he’d protested over and over. “I never thought that. If I met myself on the street, I’d think nothing of me.”

He’d decided long ago, when he was ten years old, that he wanted to act. But he never dared tell anyone. He was so shy and so tall and gangling that he thought they would have made fun of him. And even after he started making movies, whenever anyone on the set laughed during one of his scenes, he was sure they were laughing at him.

He’d gotten over a lot of his shyness, though. “You can’t make over forty movies in ten years without loosening up a bit,” he’d said recently. And when people told him he had become a good actor, he was pleased, but added honestly: “I should have. If you don’t learn anything after making as many movies as I have, you’ve got to be stupid.”

He could laugh at a lot of things now that had seemed pretty terrible at the time. Like the night he had gone to a party and suddenly found himself standing next to Ingrid Bergman. She chatted easily with him but he couldn’t think of a thing to say until finally, in desperation, he said in a loud voice: “Gee, you sure are tall.” Trying to hide her smile, she’d answered: “So are you.”

And the time he was introduced to Barbara Stanwyck and she mentioned one of her early movies and the year it had been made. He was so embarrassed that he hadn’t seen it, he blurted out truthfully: “I don’t remember it. I was only four years old at the time.” He was horrified at what he’d said, but it didn’t keep them from becoming friends.

He wasn’t the kind of person who needed a lot of friends, but he’d made some very good ones; people like the Barclays, he thought, and waved to Mrs. Barclay who had just arrived at the boathouse. He started to run down the pier toward the Hello, then, remembering, quickly slipped on his sneakers.

As soon as they got on board, the pilot cast off and for a while, he kept the boat close to the shore so that Mrs. Barclay could point out the landmarks that had made the Lerin Islands so famous. Then they headed out to sea on their way to Sainte Marguerite Island, where they were to have lunch. “ ‘Man in an Iron Mask’ was made there,” Mrs. Barclay said, and, remembering how gloomy the setting of that movie had been, he thought it was a strange place for lunch.

She must have read his thought, for she said: “Don’t worry, Rock, it’s a beautiful island, and the restaurant is excellent.”

He laughed and stretched lazily in his chair.

“I couldn’t have asked for a better ending to my vacation,” he said, opening one eye long enough to look over at Mrs Barclay.

“It’s not over yet,” she answered and they both laughed.

But he meant it, he thought to himself. He had really enjoyed this trip. Maybe part of the fun was traveling under a different name and being able to go around without people recognizing him. He hadn’t been able to do that for a long time and it gave him a strange sense of freedom . . . the way he had felt after he’d gotten out of the Navy before he went to Hollywood.

In Paris, he’d stayed at a wonderful, old, shuttered hotel that faced onto a quiet square. Days, he’d wandered up and down the narrow cobblestone streets of the Latin Quarter, rummaging through antique shops, finding rare collector’s records, buying fresh fruit at the outdoor market and thumbing through the old books and prints in the stalls that lined the Seine.

He took long siestas in the afternoon and almost every night he went to the Kwai Samba, a Senegalese night club that was a favorite hangout of visiting actors. Marlon Brando always went there when he was in Paris and played the bongo drums with the band.

They had a good orchestra and all sorts of exotic African foods he’d never heard of, like palm tree hearts. A couple of times he found himself wishing Jim Matteoni were there. Jimmy had been his closest friend ever since grade school and they had both been crazy about jazz. In fact, somewhere in his collection there was a record they’d made together with Jim playing the piano and him talking the lyrics.

“It’s strange,” he thought to himself now, rocking easily with the steady movement of the boat, “that so many things seem to remind me ot things that happened before I went to Hollywood. It’s probably because I haven’t relaxed so completely in a long time.”

The warmth of the tropical sun and the drone of the motor fulled him to sleep, till a spray of cold sea air was dashed against his face. He awoke, startled, and for an instant, blinded by the brilliant sunlight, couldn’t remember where he was.

Mrs. Barclay noticed he was awake and called: “We’re almost there. That’s the tip of Sainte Marguerite up ahead.”

Rock shaded his eyes with his hand and tried to see but the glare was too strong and he leaned his back against the rail. The pilot was saying something in French and Mrs. Barclay explained: “He says there’s a motorboat over there,” she pointed, “pulling a water-skier.”

“Jump!”

“Wish I’d had more time for that while I was here,” Rock said, turning to watch the motor boat speeding toward them.

“Hey, what’s the matter with him!” Rock suddenly asked. “Doesn’t he see us?” And both he and Mrs. Barclay started yelling and waving to the other pilot.

But the man was looking behind him, at the skier, and didn’t notice them. The Hello’s pilot frantically tried to change his course, but he couldn’t, and as they watched, horrified, the boat sped closer, heading straight for them.

“Jump!” Rock shouted to Mrs. Barclay and the pilot and, even as he started to dive after them, the boats collided.

He heard the splintering of wood and saw the flash of the green, white and red Italian flag, still gaily flying from the other boat, as it bounced through the air and seemed to sail right over the top of the Hello. Then he hit the water.

It was cold and the backwash from the two boats crashed down on him and stunned him. Only half-conscious, he felt himself sinking, the weight of his body and his wet clothes dragging him down, deeper and deeper, into the blackness of the water. Then he must have blacked out.

Hours later—it seemed like days—after they had been picked up and brought back to the port of Cannes, Rock and Mrs. Barclay were sitting before an open fire, wrapped in blankets and drinking hot coffee.

Rock sat thinking a long while and then said: “You know, when I hit that water, I didn’t know if it were really happening, or if I were dreaming again. There are two dreams nightmares really, that I have over and over. One, I’ve had all my life. I guess it must have something to do with claustrophobia. It’s always the same, the inside of a tool shop. As I walk through the door the tools that are lined up on each wall start closing in on me and finally I wind up sitting at a little machine with a tape running through it and a crazy needle making marks on the tape. After, I wake up in a cold sweat.

“The other,” he stopped talking and sipped more coffee, then went on, “the other one’s where I dream I’m drowning. It’s terrible at first, but then I get so I can breathe under water and I swim all around and have a hell of a time! It was like that today.”

He was silent for a few minutes, then said: “You know, it’s funny. Last time I had that dream, I told some people about it and an older woman who was sitting with us said: ‘Be careful! Dreams can come true, you know.’ She got mad when I laughed,” he added. “I wonder what she’d have to say about what happened today,” and then, as though he wanted to chase the thought away, he stood up and tossed off his blanket.

“Guess I’d better start packing or I’ll miss the train to Portofino.”

—G. DIVAS

Rock can be seen in “The Day of the Gun” and “Come September” for U-I

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1961

AUDIO BOOK