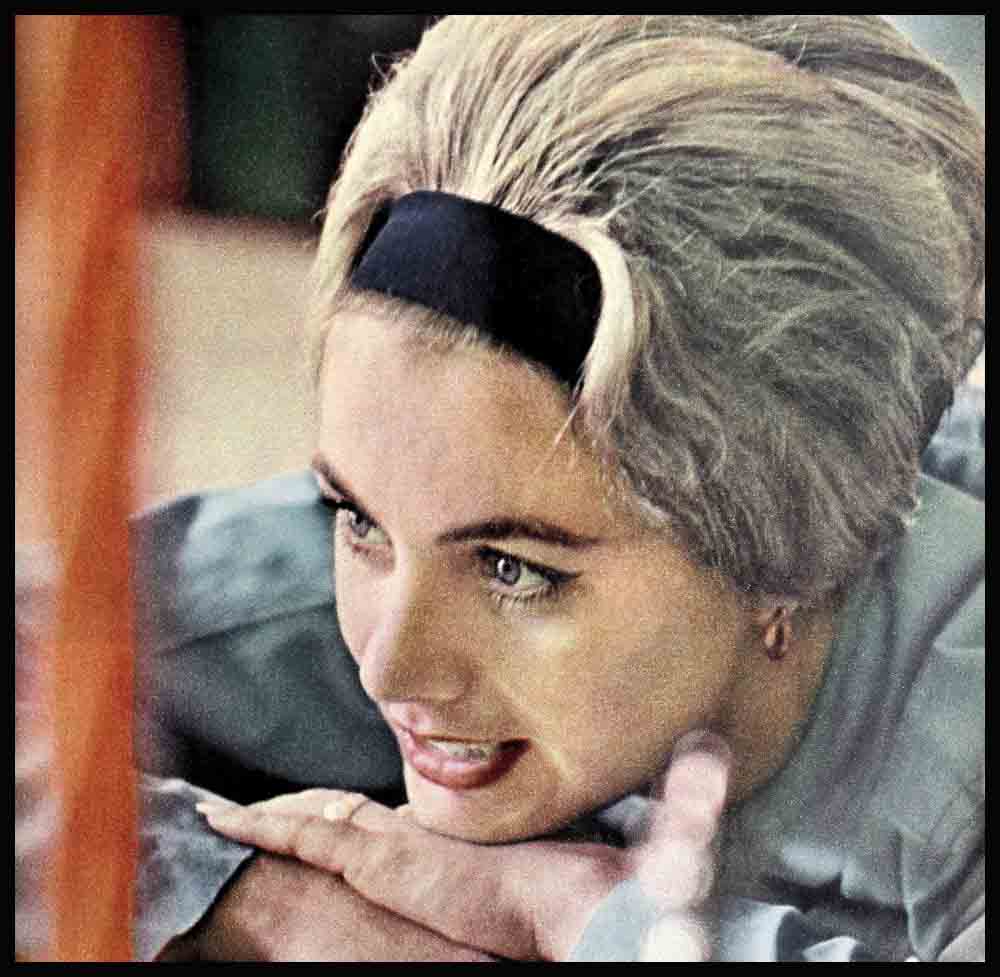

The Daredevil With The Apple Pie Face

At Shirley Jones’ last party, three guests jumped in the swimming pool and two poodles got drunk on champagne. Shirley admires people who are uninhibited enough to strip to their underwear in someone else’s living room on a hot night and then go searching for a vacant swimming pool. And she once walked off the set of a multi-million dollar movie to take a helicopter ride with a friend who had never flown one before. She is a daredevil—a “good girl” who had to become a prostitute on the screen to win friends and influence people. Despite this, she goes to sleep at 9 P.M. and wakes cheerfully with the California sparrows at 6 A.M. She breakfasts ritually on orange juice, eggs and bacon before anyone else in Bel Air—including her husband—is even turning over in their dream-tossed sleep.

Shirley was nineteen when she came to Hollywood as Laurie in “Oklahoma.” Plump and pretty, she looked like a picture postcard out of the nineteenth century, and she was contemptuously dismissed as “that empty-headed farm girl.” Six years later she won I an Oscar as a slut in “Elmer Gantry”—and after that she’d get pinched on the thigh and asked to “tell me where you got the experience to play that prostitute, Lulu Baines.”

Actually, Shirley is neither character. But as one producer who has worked with her says, “There’s a helluva lot more of Lulu in Shirley than there is of Laurie.”

She grew up thousands of miles from Oklahoma, but her childhood was the essence of small-town America. Even her name conjures up pictures of vanilla ice cream, home cranked; of watermelons on summer picnics; of pale blue ruffled dresses and ghosts on Hallowe’en. One wonders whether Rodgers and Hammerstein were not perhaps subconsciously influenced by the superstitious rightness of her face and her name.

There were 800 people in Smithton, Pa., including the three Joneses. Grammar school was a three-room frame schoolhouse with three grades in each room. Shirley walked home for lunch each day, went barefoot all summer, learned to swim in the Yaughagenny River.

“Dinner was at 5 P.M. each weekday for ten years. Every Saturday I washed my hair and every Saturday night I went to the movies. After church on Sunday we walked home to the big weekly dinner of chicken and homemade noodles.

“Anyone in the world would have bought my childhood if it had been offered for sale. I wish my children could have it, too, and yet I wonder if it would be good for them in this complicated world in which they’re going to live.”

She was a responsible child, pleasant and well-mannered. filled with the “solid security of being an only child and having no competition.” Yet even then she was ferociously strong-willed. (As strong-willed as Lulu Baines who was seduced, betrayed, locked out of her father’s house—and never even thought of begging to be allowed back.) And so she was spanked every day by a strong. determined mother who eventually despaired of teaching her equally strong Shirley moderation in anything. She was the first kid chosen for all the boys’ sandlot football and basketball teams. She could outrun, out-shoot and out-tackle any boy in Smithton—until they finally grew tall enough to throw the ball over her pretty little head.

Prim—but oh, my!

At that point she graduated to other “sports.” Anything that was considered too dangerous by the others was her first choice for an afternoon’s fun. She went skiing without skis, jumped off any walls, trees or houses that were tali enough to scare everyone else. She drove too fast down every rutted country road within fifty miles of Smithton. And at eighteen she went alone to New York to become an actress.

Then—as now—her appearance was deceiving. Today the plumpness has disappeared, but the rosy cheeks remain. conveying an illusion of sweet simplicity. As a result she shocks everyone who has gotten to know her more than superficially.

She loves to argue—sometimes merely for the sake of arguing.

“You look so sweet.” said one angry actor a few months ago. after Shirley had demolished him with a flood of statistics. “I would never have believed you were so—so damn opinionated!”

She loves to dare—sometimes merely for the sake of daring. When she was in Kentucky. filming “April Love,” the cast spent one Saturday at a horse show. Shirley was fascinated by a white stallion so spirited his own jockey couldn’t control him. When the show was over, she trailed horse and jockey to the parking lot.

“He’s beautiful,” she said. “The most wonderful horse I’ve ever seen. I’d give anything to ride him.”

The jockey hesitated. “Do you ride?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you ride well?”

“Terribly. terribly well.”

The jockey found it impossible to refuse.

As soon as her feet touched the stirrups. the stallion lunged wildly. There was no place for him to run in the parking lot, so he plunged against Cadillacs and pickup trucks, then desperately jumped across a small foreign car. By the time she managed to bring the horse under control. the producer of “April Love” was leaning. White-faced, against his rented limousine, and the jockey caught hold of the stallion’s bridle with shaking hands.

Of all the people in the parking lot that afternoon, only Shirley Jones was not afraid for Shirley Jones. She slid casually out of the saddle even though her arms and legs were covered with bruises that would not disappear for weeks.

“Anything you can do . . .”

She has a cocky confidence that would seem more natural in Marlon Brando or Dr. Ben Casey.

“I’ve never failed at anything,” she says. “ I’m strong, realistic and efficient. I have great stability and security. Few things can rock me.”

She has just started to take tennis lessons. Within a few months she expects to be playing well. “When l set out to do something.” she says, “I usually accomplish it. I know I’ll be good at tennis.”

Her days are spent in the wholesome trivia of living. She bathes one-year-old Patrick; she takes four-year-old Shaun to the supermarket; at the supermarket she compares can sizes and prices in a search for bargains.

Although she has a gourmet’s taste in bizarre friends. she makes no attempts to imitate them. She delights in the company of people who have no inhibitions about mountain climbing at 4 A.M., but she is content to remain a “day” person.

From childhood she has liked to be awake at the start of a new day. “To me the morning is so exciting. Night is nothing except the end.” She still does not quite understand why her husband—who likes to stay up until 3 A.M. even if only to watch television—feels that night is “the beginning.”

She cooks her own meals and takes care of her own children. The multi-bedroomed house in Bel Air is a long way from Smithton, Pa. The tables are topped with marble, their pedestals covered with gold rosettes. The sofas are thick with orange and green velvet. A marble urn overflows with artificial grapes. Everything is gilded and ornate. Yet much of what fills the house in Bel Air are dreams and responsibilities that began in Smithton, Pa., where chicken was served every Sunday.

“My father was a sweet. marvelous, human being,” Shirley says. “He was a giving, sunny man whom I adored. All of my fantasy comes from him. On summer afternoons he would take me to a double feature. Then we would walk home for sup per. After supper we would go back to another double feature. My mother is a very strong woman. She hates movies.” Shirley laughs. “I really think that, to her, one of the worst things about my being an actress is that she feels she has to go see my pictures. All my ideals and my strength come from her. My parents complemented each other, and I inherited the good from each of them.”

Implicit in her voice and in a nervous motion of her hand is her one worry—what effect a less sheltered childhood will have on her own sons.

“Becoming a prostitute gave me status in my professional and private life,” she says. “After ‘Elmer Gantry’ I was lionized. People who would never talk to me before invited me to their parties.”

She shrugs. “I’m not afraid of leeches. I’m a good enough judge of character to know if someone is trying to use me. But the children are too immature to discriminate, and people have already started to try to use Shaun.”

“Mommy,” Shaun said a few days ago. “I’m a star.” Just like that—a star.

For a moment Shirley didn’t understand. “You mean a star that shines in the sky?”

“No.” He tried to explain something he was too young to make sense of. “They told me some mommies and daddies are stars, so I’m a star too.”

Shirley does not know who “told him,” nor will she ever be able to find out. At the moment. Shaun is still too young to understand what he is being “told.” He listens without comprehending.

“Have you ever been in Oklahoma, Mommy?”

“You mean the State of Oklahoma. like we live in California?”

He nods his head.

“Yes, I w as there once.”

For the moment, that is the end of it. But in a year or two he will know that his Mommy is different because she is a motion picture star and that he is different because she is his Mommy.

She remembers back to her own childhood and says again, “But maybe my childhood would he too simple a preparation for the complicated world in which Shaun and Patrick will live.”

Having children has changed her more than fame was able to. The girl who dared a helicopter ride with a man who had never piloted a helicopter is afraid of flying now. The girl who drove down rutted country roads at sixty miles an hour insists on buckling her safety belt.

“I never had anyone dependent on me before,” she says. “Jack was responsible for me. Now Em responsible for two other people.” It is a responsibility that she accepts in as casual a fashion as she has ; accepted fame and money.

“Maybe I haven’t had as great a life as I imagine.” she says, “but I think I did. Maybe the rest of it won‘t be as good. But I think it will. And that’s all that matters.”

—ALJEAN MELTSIR

Shirley’s in “The Music Man,” WB, and “The Courtship of Eddie’s Father.” M-G-M.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1963