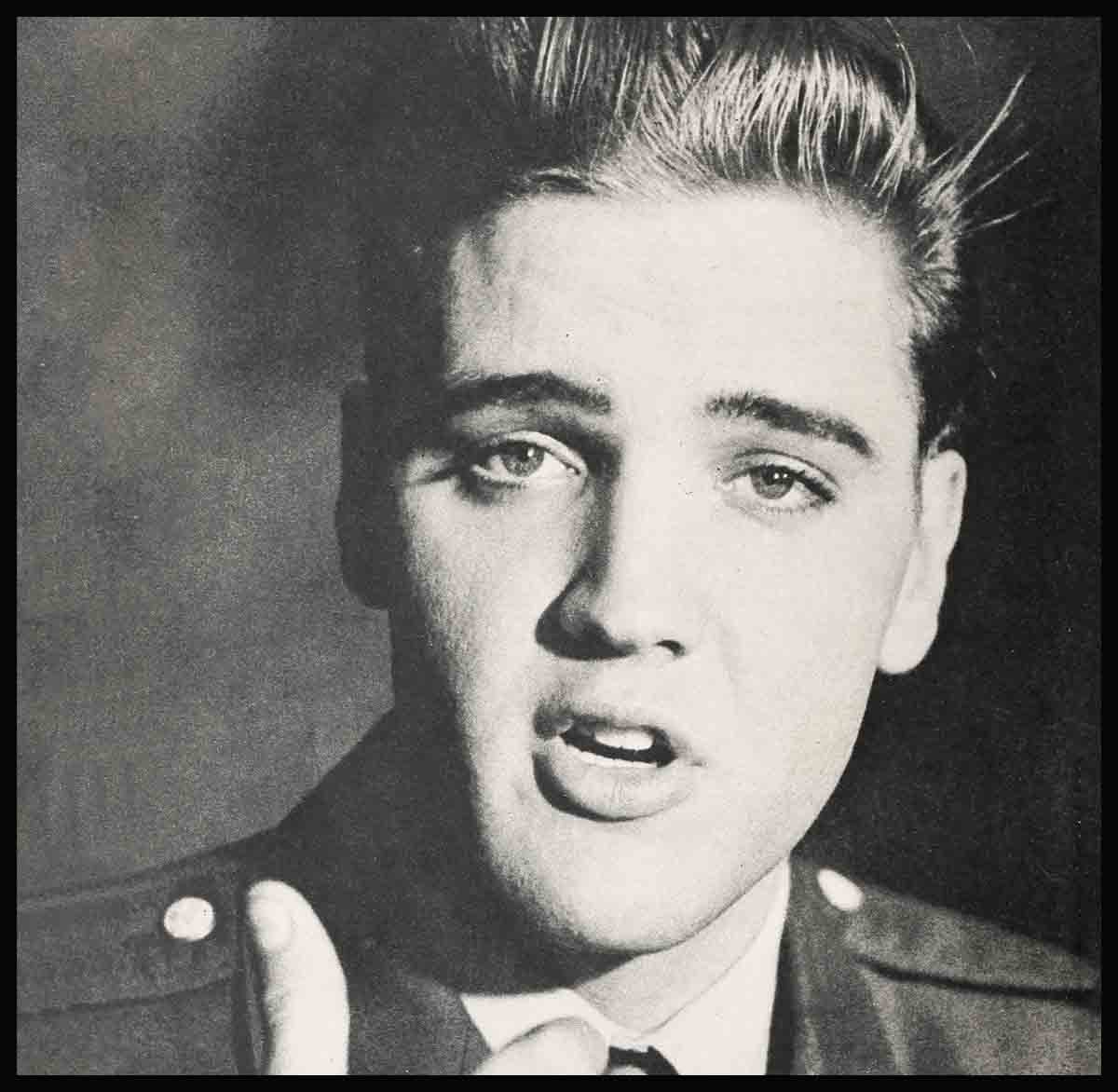

Rock Hudson’s Personal Letter To You

November 1, 1958

Hollywood, California

To All of You:

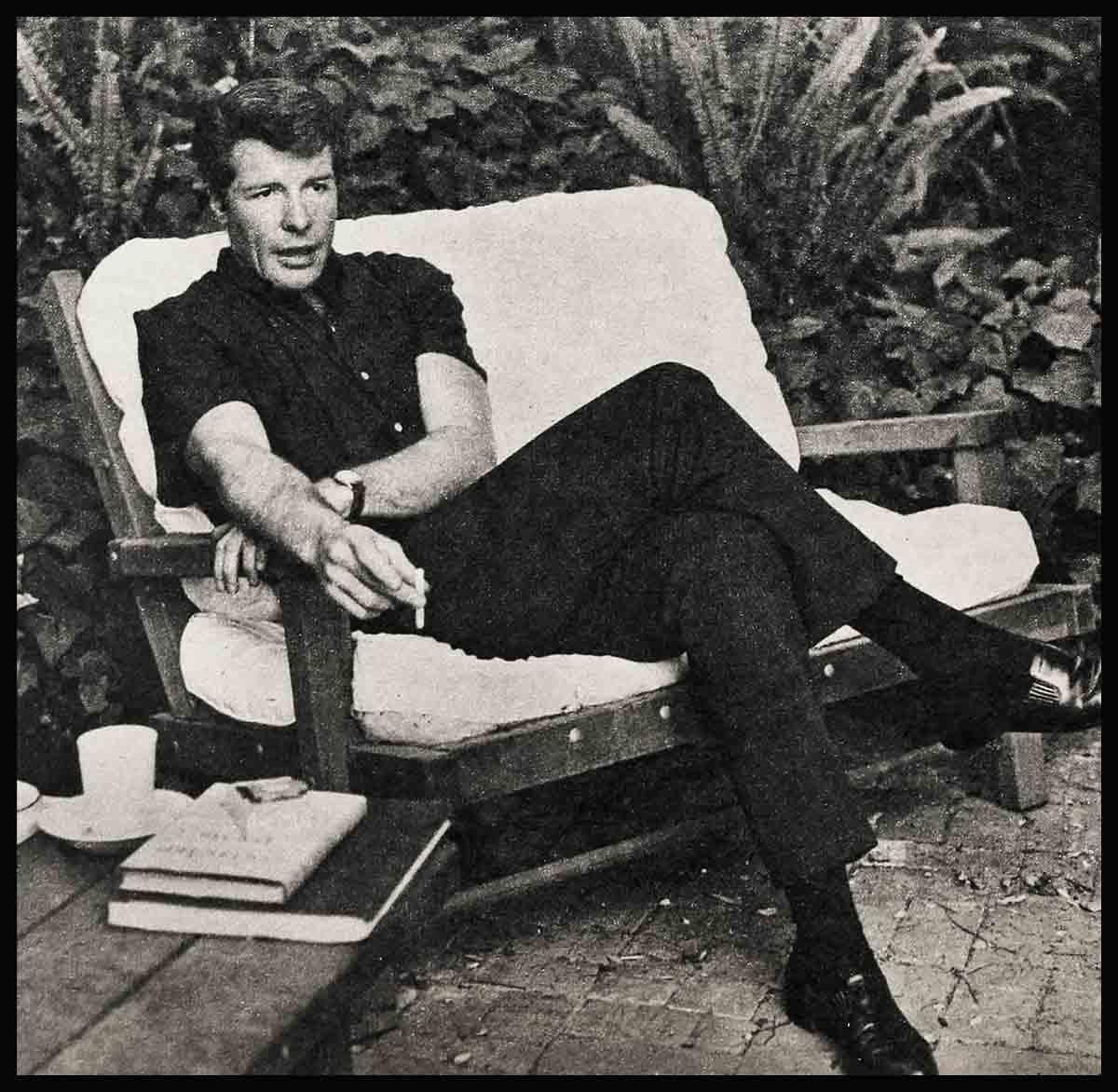

It’s almost dark now, but not quite. It’s twilight time, a halfway time between night and day that’s always held a kind of magic for me. It’s a time for catching your breath. . . for daydreaming . . . for writing letters to very special friends.

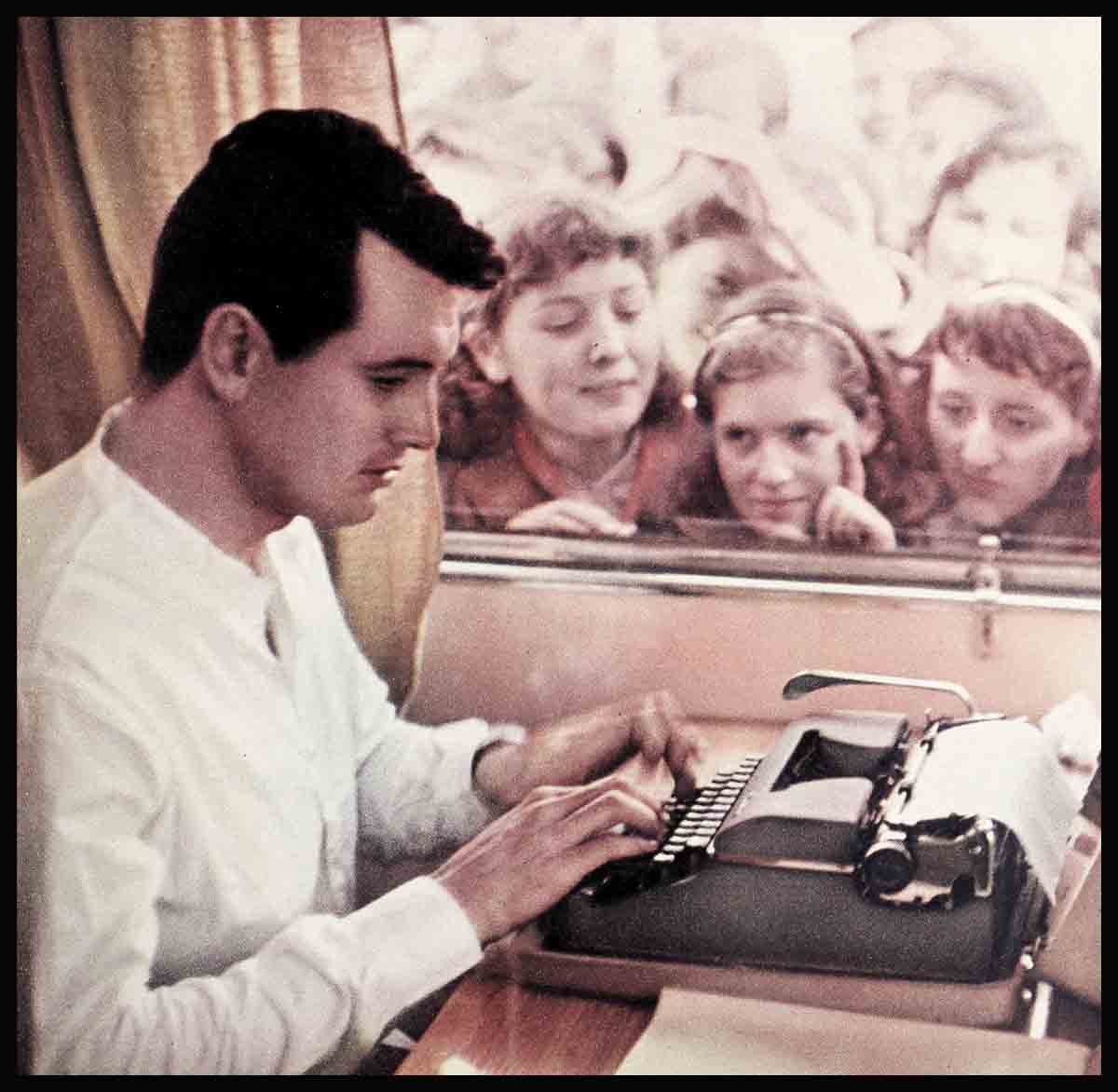

I’m living in an apartment now, just a living room, one bedroom, bath and kitchen. Instead of a view of lawn and trees, my windows look out upon other buildings. As I sit here at my typewriter, there aren’t the looming, lit-up shapes of New York. But still I guess just apartment living reminds me of New York.

Two years ago, on Broadway, there was a play running called “Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?” Later it was made into a movie. I took a lot of kidding from my friends when it became a hit, because it didn’t take much of an imagination to know that any connection between the title and someone you know was strictly intentional.

It was a good joke then, but now I find that some of the humor has gone out of it for me. Lately I find that a good many of the people I used to consider my friends-my fans-have been hearing several unflattering (to say the least) things about me. I’ve been taken to task for going “arty.” I’ve been criticized for my divorce from Phyllis. And it’s been whispered-often behind my back-that I’m moody and difficult to work with.

Sometimes when I hear the charges I feel hurt and kind of helpless. What can I do about it? What can I say?

After giving it a great deal of thought, however, I decided that there was something I could do. . . . there was a good deal I could say.

I could take my pride in my hands, for instance, and sit down at my typewriter to tell you a little about me—things, perhaps, that have made me what I am today; the emotions that are part of me and the feelings I’ll never grow out of. I hope, after reading this, that you will decide that the title of this article could have been “Success Has Not Spoiled Rock Hudson” (with apologies to George Axelrod, author of the famous play).

Maybe I don’t look the type, but I’m as vulnerable as most people and perhaps more sensitive than many—and many of the things being said about my divorce from Phyllis hurt a good deal.

No two people ever enter a marriage, I think, unless they firmly believe that “This Is for Always.” Phyllis and I did, too. We were in love for a long, long time before we considered marriage, and we thought long and seriously before we entered into it. We were in love, and we wanted to live the rest of our lives together. It was as simple as that.

I’d met Phyllis Gates in Henry Willson’s office, where she was a secretary. It was a long time before we ever had our first date together. And when we finally did, after we’d met casually in a five-and-dime store on a lunch hour, it seemed natural and right. We had such a wonderful time when we were going together! We shared the same private jokes, we liked to dance to the same kind of music, and we liked to do the same things. We had gone out together for more than a year before I asked her to marry me and she accepted.

Things were fine at the beginning. We had a wonderful honeymoon in Jamaica, and then we spent a memorable week in New York before returning to Hollywood. The first few months of our marriage were the happiest of my entire life.

We both wanted a nice home, and set about finding and furnishing one. We both wanted children, and we would talk about them and plan for them for hours on end. And then, without any warning, things began to change.

I can’t tell you how painful it is to be living with a person you used to be in love with, and then having both of you discover that for whatever the reason—or reasons—you aren’t in love with each other any more. The feeling must be something like stepping onto what you think is firm, solid ground—only to discover that instead you’ve been trapped in quicksand. You sink and sink, and all of your struggles and efforts to maintain your balance and equilibrium serve only to make things worse. You know you have to get out if you’re going to do anything at all with the rest of your life. And you have to get out fast!

It’s been more than a year since the break-up of our marriage, and I still find it painful to think about it, and downright impossible to discuss it. Neither Phyllis nor I have ever been great “talkers,” and neither one of us has been able to discuss our marriage or the reasons why it disintegrated into divorce. I think we both feel that there are some things which should remain part of the relationship between a man and a woman, and that it is something which the rest of the world can neither help nor hinder. Talking about it wouldn’t help, and might even serve to destroy whatever was still left that was beautiful: a memory, perhaps, or a feeling that still remains for the way things were in the beginning.

I’m sorry that my marriage failed, sorrier than I am about anything that has ever happened to me. But to criticize me for it is to criticize a man for being ill, or for having been involved in a traffic accident. It’s something I regret, and something I couldn’t help. And yet I know that there is no way to undo the past.

I’m not against the institution of marriage. I’m all for it, and someday I hope to find what will be the right girl for me, and I’ll marry again. I can’t be “soured” on marriage, for as a way of living it has too much in its favor. Certainly in my own family I’ve had an example of a bad marriage followed by a good one. My own mother had two unfortunate experiences before she met and married Joseph Olson, to whom she’s married now. And the experiences she had with Roy Scherer (my father) and Roy Fitzgerald (my stepfather) seem only to serve to underline her current happiness.

Some of my critics, and I hope you aren’t among them, have said that I’ve gone “arty.” Well, if that means having a look at a book now and then, I’m guilty. I’ve had lots of fun reading lately and among the books I’ve liked are “Anatomy of Murder” by Travers, “A History of the English Speaking Peoples” by Churchill, “Ice Palace” by Edna Ferber, “By Love Possessed” by Cozzens and “Book of the Seven Seas” by the late Peter Freuchen.

If going “arty” means that I’m learning to appreciate the finer things in life—such as opera, for instance—well, I’ll have to admit I am. I’ve always had a feeling for music. Before I was married, I owned a record collection that filled a couple of bookcases. My tastes ran from Bach to boogie woogie, from Jan Pierce to Bing—But I admit that opera left me cold.

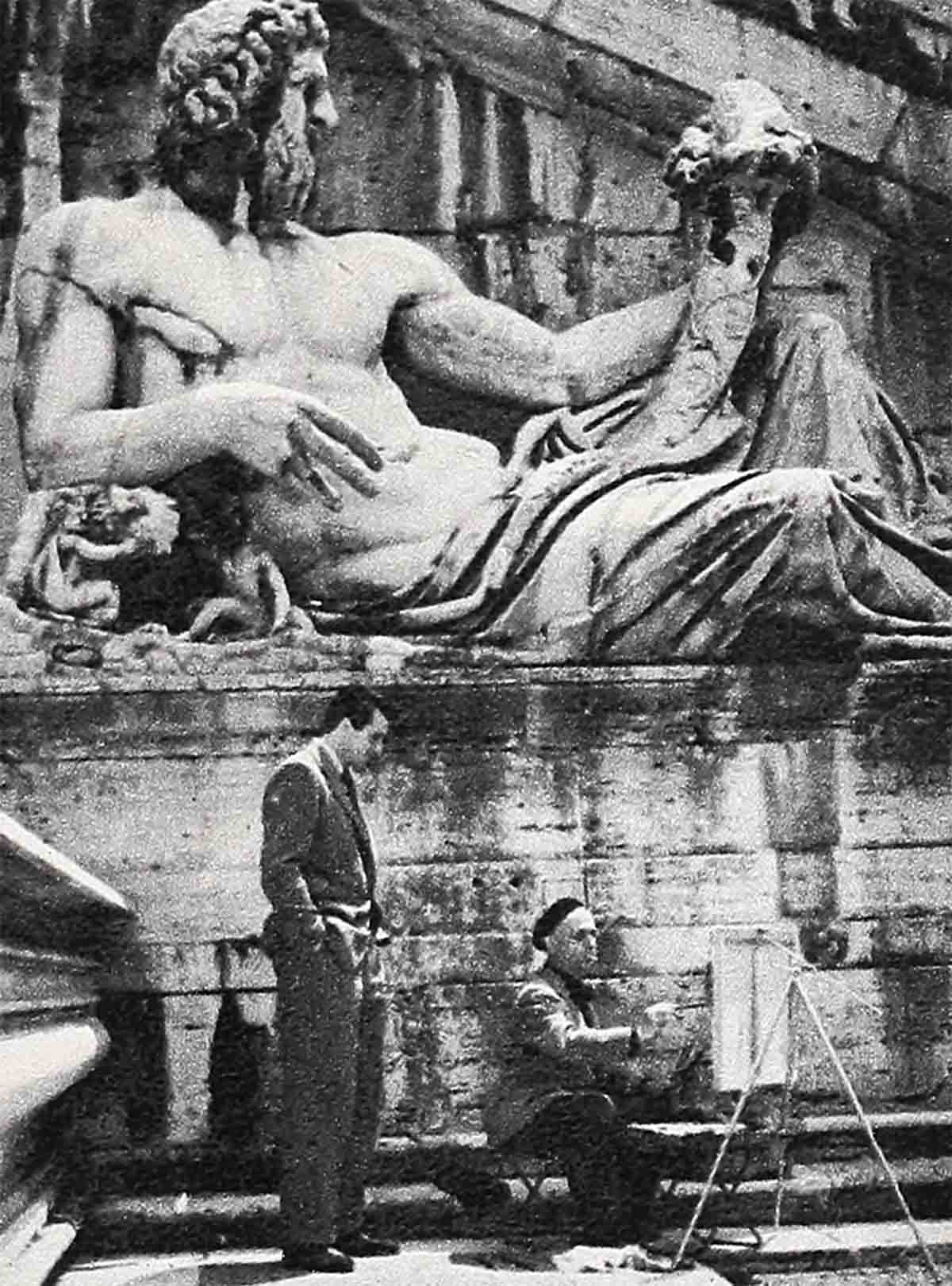

And then, in the fall of ’57, I went to Italy to make “Farewell to Arms.” Vittorio de Sica, who’s famous as both an Italian actor and director, invited me to hear “Il Quattro Rusteghi,” by Wolf-Ferrari. I went, and my first reaction was, “Why haven’t I discovered this before? It’s wonderful!”

Italy may be an opera-loving country, but those Italians sure know what to like. I came away so thrilled and excited by my introduction to the opera that I’ve never forgotten it.

Back in Hollywood one day, I was telling my friends about “Il Quattro Rusteghi” and I burst into song for the main aria—just like that. A week later, I discovered that the University of Southern California School of Music was presenting a performance of it, and I decided to let my friends hear the real thing. I bought four tickets and we made an evening of it.

Hearing the opera for a second time convinced me that I’d “discovered” a new world of enjoyment which had been waiting for me all along—and where in the world had I been? I caught nuances of the music I’d missed the first time, the bits of action, the minor musical themes. They say you aren’t a real opera lover until you’ve seen and heard one work at least eight times. If that’s the case, then I’ve a little ways to go—but I’m willing to go there. Does anyone know where they’re singing “Il Quattro Rusteghi” sometime soon?

All kidding aside, though, does the fact that I’m learning to appreciate the opera mean that I’ve changed? I don’t think so. To me, living means growing, and the ability to broaden your horizons. You grow. Your horizons widen. Your appreciation broadens. Your attitudes change. But you don’t change.

You’re still the guy who once was more at home with grease on his hands than greasepaint on his face—and you hope you’re still the guy who has both feet on the ground and his head where it belongs.

To begin with, let’s answer the charge that I’m going “high hat.” I can’t believe it. I’ve had to work too hard for what I’ve achieved and chalked up too many painful memories in the process ever to change.

I love people, but I like to feel comfortable with them and I want them to be comfortable with me. I had lunch not long ago at the studio, with a girl who was visiting. To her, I wasn’t a person: I was a movie star. She couldn’t speak.

I leaned across the table and I smiled at her. “I didn’t know there was such a color as warm blue,” I said, “till I saw your eyes.”

“But my eyes are green,” she protested.

“They’re blue,” I insisted. She dug into her handbag and pulled out a small mirror. She checked her eyes in it. “They’re green,” she said. Well, by the time I was willing to admit they really were green, she’d relaxed. She was ready to be herself and to take me for myself. It’s important to take people for themselves. As I sit at my typewriter now, I can remember when I first learned that. I learned it from a little boy back in Winnetka, Illinois.

As a kid, I knew what it was to be lonely. My father, Roy Scherer, deserted my mother when I was six years old, and I went to live with my grandmother. My mother was away most of the day working as a switchboard operator, and I felt that “loneliness” was a word that had been invented for me.

When I was nine, my mother married Roy Fitzgerald, and things got a little better, but not much. We were poor, and I started earning my way early. I delivered newspapers after school, and got a job as a fireman in the power plant. And when I was twelve, I learned something I’ve never forgotten. I learned it from a boy named Eddie Jenner.

Eddie was a boy who lived on the Hill Road side of Winnetka, but I never gave it much thought. Often, we’d walk home from school together, talking about what we were going to do when we grew up, and about the thousand-and-one other things that seem so important to you when you’re twelve years old. Sometimes Eddie would call his mother from my house, and stay over while Mom rustled up some tuna fish and canned green peas for dinner.

And then one day his mother sent a note to my mother asking her whether I could come to their house for dinner. Mom said “Yes,” and off I went.

I wasn’t at all prepared for what I saw. His “house” had more rooms in it than our local hotel, and there was a huge swimming pool right outside it. They had an acre of ground, and a tree-lined road outside the house, and inside it there was a butler and a maid. When I sat down at the table, there was a tablecloth and napkins, and lots of highly polished silverware. We had artichokes for dinner that night, and steak and a salad, ice cream and milk—and all I could think about all evening long was that the last time Eddie Jenner had been at my home we’d eaten on the plastic-topped table in the kitchen, and my mother had served tuna fish and canned green peas. I’d never felt as much like an outsider before in my life—and I wanted to run. Eddie noticed that something was wrong, and after dinner he asked me whether I wanted to take a walk. I certainly did!

When we got outside, I turned and looked directly at Eddie. “You never told me you lived in a house like that!” I said accusingly.

“Like what?” Eddie asked, puzzled.

“The maid. And the butler. And all that polished silver on the table . . . and artichokes and steak for dinner . . . and a swimming pool . . . and two kinds of ice cream for dessert. You’ve been to my house, so you know what I mean. We’re just different, that’s all. We can’t be friends any more!”

Eddie stepped back as though I had struck him, and for a minute I thought he was going to cry. But then he clenched his fists, and he got so angry that his face turned red.

“You big lummox,” he shouted. “It’s people that count—not things! Don’t you know that? You can’t help it if you live in your house. And I can’t help it if my house has a swimming pool. I want you for a friend because I like you as a person.”

Eddie Jenner and I were good friends until he went off to military school in Arizona and we lost track of each other—but I’ve never forgotten that evening, and what he said. “It’s people that count, not things.”

Sure, I could afford a house with a swimming pool now, if I wanted one, and I could have a maid and a butler too. But I don’t think I do. To me, just as it was to Eddie Jenner, it has always remained people that count, notthings. If Eddie Jenner, a kid just twelve years old could have recognized the values which are important in life, then certainly I ought to be able to as an adult. I’ve never forgotten that evening, and I hope I never do. I don’t think I’ll ever turn “high-hat” either. I’ve worked too hard and tried too long before the breaks started coming my way ever to forget it. And besides, too many other people were involved with my getting there for me ever to forget them. Henry Willson for one. And George Stevens for another.

They’re both on my special mailing list. After I’ve sat through a picture-taking session with the studio, I get a chance to inspect the results. Some of these results are pretty horrible. These are the pictures I take for my own use—pictures that have caught me with eyes closed or my mouth open. I send them to good pals like Henry and George. Who are these men? What do they mean to me? Well, perhaps I’d. better explain.

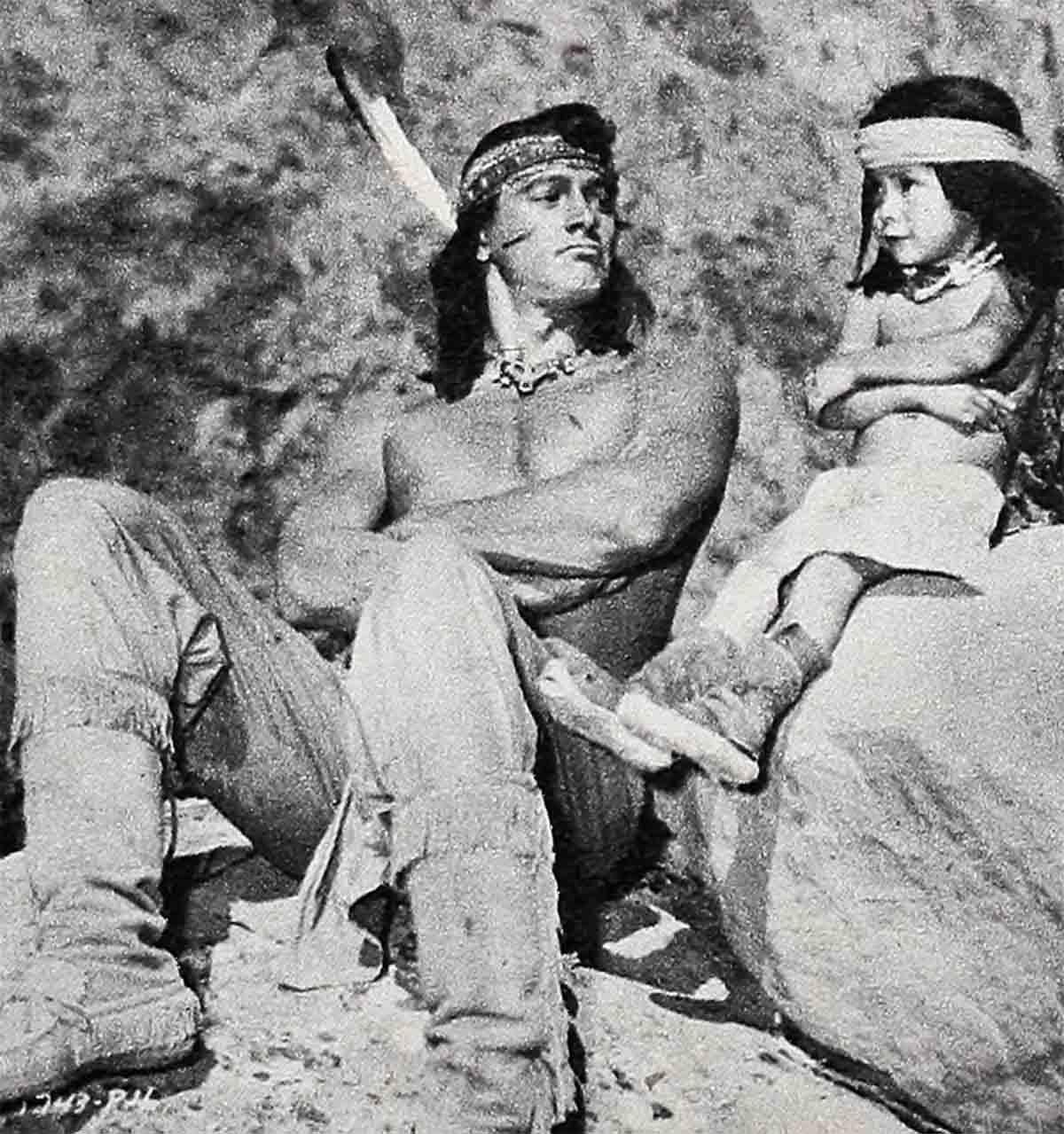

I’d wanted to be an actor ever since I was a kid and went to the movies to see Jon Hall leap from a crow’s nest into the sea. Seeing him do that did something to me, and I knew that I had to get into the movies or be unhappy for the rest of my life.

However, it took a good many years, and a hitch in the Navy before I could put that dream to work. I held onto the dream, though, and it was that dream at the back of my mind that sent me to California in 1946, intending to live with my father and study at the University of California. The University wouldn’t accept me, and I couldn’t live with my father. So, with that dream still at the back of my mind, I got a job driving a truck for the Budget Packing Company, delivering dried beans to grocery stores.

Believe it or not, I really believed those stories about how movie stars were “discovered,” and every time I’d get within sight of a studio gate, I’d pull my truck up against it and stand beside my truck, nonchalantly puffing a cigarette in my best about – to – be – discovered manner. Nothing happened. I chalked up about 250 hours of “waiting for D-day” (in this case D meant Discovery) before I gave up.

And then one day a friend of mine told me he knew a talent executive at Selznick Studios and suggested that I have some photographs taken. It cost me twenty-five dollars, which was three full days’ pay in those days, but I got the pictures made. That week, I had to borrow a dollar for dinner or go hungry. But I kept my appointment with Henry Willson.

I don’t think anything important ever happened to me before I went into Willson’s office. He was, at the time, Selznick’s talent chief, and—with a couple of thousand dollars of his own money—he staked me to acting lessons and the rest: lessons in diction, drama, riding and fencing. For a solid year, I ran my truck daytimes, and took lessons every night.

To this day, I can thank Henry Willson for having had faith in me, and for believing in me enough to get me started in pictures. He’s been my agent all the way through, and I still consider him one of my best friends.

George Stevens was the director of “Giant,” and is a man of infinite wisdom and capability. He’s a wonderful director, but more than that, he’s a heck of a nice guy.

The night before we started “Giant,” I wanted to call the whole thing off. I had a bad, bad case of the jitters. “I’m not good enough for the role,” I wanted to tell him. “It’s too big for me. You’ve got the wrong

After sitting through a whole afternoon in the doldrums, I picked up the telephone to call him and intended to tell him exactly how I felt. “I’ll get it out and get it all over with!” I told myself as I dialed his unlisted phone number.

“Hello, Mr. Stevens,” I said when he picked up the phone. “This is Rock Hudson.”

Something must have been there in my voice, for he asked, “Is anything the matter, Rock?”

“Everything’s the matter,” I blurted out. “I’m not ready enough.”

George Stevens laughed—and the laughter sounded so good that before I knew it I had relaxed my grip on the telephone and the butterflies had stopped fluttering around in my stomach, for the first time that day.

“You know something?” he asked quietly. “I’ve got stage fright too. I always get stage fright at the beginning of a picture.”

“But I don’t understand the character I’m supposed to be playing,” I wailed, and I heard my unhappiness transfer itself across the wires of the telephone.

“Maybe I don’t either, Rock,” he said calmly. “Let’s figure him out together, you and I.”

“Okay. If that’s the way you want it, Mr. Stevens,” I said slowly. Then we said good-night.

I thought of that conversation the night I was up for an Academy Award for “Giant,” and many times since then too. I’ve been grateful to George Stevens for believing in me, and I’ve been grateful to my studio for allowing me to make that picture.

I’m fully cognizant of the fact that U-I has done a great deal for me. But I’m both confused and hurt by the rumors that I’m difficult and a problem to work with these days. Sure, I was disappointed when Charlton Heston got the role I wanted in “Ben-Hur,” when the studio wouldn’t loan me out. It was a good picture, and one I wanted to make. I had a good break in “Magnificent Obsession” and another one in “Giant.” Now I’m looking for a third.

Of course it was nice to be voted tops at the box-office last year by the Motion Pictures Exhibitors and to be voted by you the Photoplay Gold Medal winner for 57. But that kind of popularity carries its own responsibility: You have to live up to your notices. Your next picture has to be every bit as good as your last, or your rating slips.

I appreciate all that U-I has done for me in the past, but I know that my next four years as an actor will be the most important I have. I hope the pictures yet to come will be the most important of my career.

If I’ve been difficult, if the studio has found me less amenable than I have been in my previous working life, it isn’t because I appreciate them any the less. It’s because I feel my responsibility to you even more. I want to make the kind of pictures you’ll be proud to see me in.

Does that sound as though I’m taking myself too seriously? I hope not. I think it is every actor’s debt to his public to give them the best that is in him, and all that I want is the kind of picture which will call for the best that is in me.

Besides, I think there are some things a person should take seriously—and work is one of them. Though I take my work seriously, I hope I’ll never get to take myself seriously. If I ever. do, I hope someone will remind me of my first “role” in pictures. It was a one-line walk-on in “Fighter Squadron,” my first movie. I was supposed to say, “Pretty soon you’re going to have to get a bigger blackboard.” Believe it or not, I “flubbed” that line thirty-eight times before they finally got a “take.”

I look back at it now, and I laugh. But as soon as the laughter stops, all the pain and self-doubt I experienced that day reassert themselves, and I’m happy I got another chance—not because of, but in spite of my first role in pictures. As long as incidents like that remain fresh in my memory, I don’t think I’ll ever take myself seriously. I couldn’t change that much in one lifetime.

THE END

ROCK STARS IN “TWILIGHT FOR THE GODS” FOR U-I AND CAN BE SEEN SOON IN U-I’s “THIS EARTH IS MINE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1958

No Comments