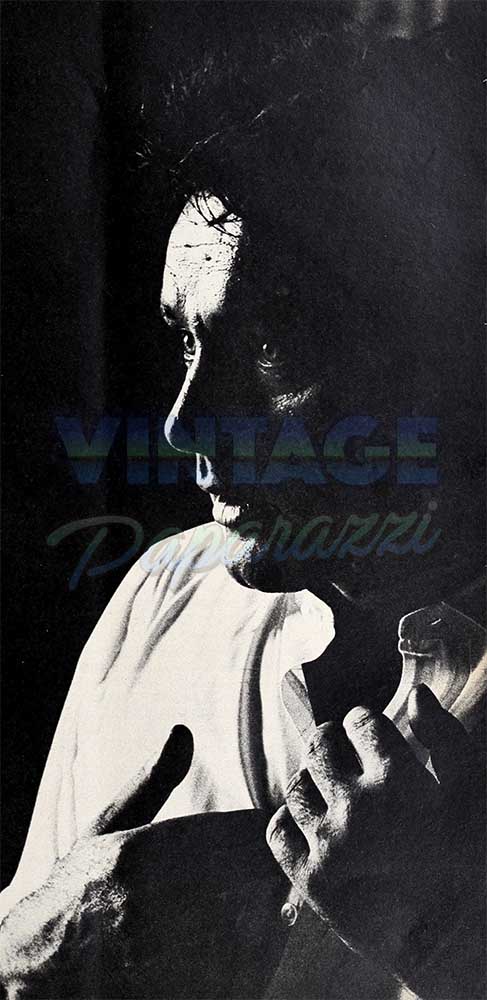

Richard Burton How He Got That Way?

PART II

Now that World War II was over, and his honorable if somewhat beerstained discharge papers tucked safely away, Richard Burton got back to serious work with P.H. Burton, his theatrical mentor. In early 1946, Richard made his professional acting debut, playing in repertory companies through- out South Wales—in Neath and in Swansea, in Cardiff and Carmarthen and other cities and towns.

In early 1947, at P.H.’s suggestion, Richard applied for a scholarship to Oxford. And to almost everybody’s amazement—except P.H.’s—Richard got it.

At Oxford, where he reportedly excelled in academic studies (he was aiming for a doctorate in Italian literature), Richard naturally took part in the university’s theatrical productions. And it was during a performance in one of these productions that he was spotted by the famous actor-play-wright Emlyn Williams.

AUDIO BOOK

Backstage that night Williams had a short talk with Richard. The gist of it was this: “Come to London. The London theater is ready for you. You, young man, are most certainly ready for the London theater.” Richard hesitated for a while—for about six months, in fact. But one day he did leave Oxford; he caught a train for the Capital of the British Empire and the British theater. And on a night in January of 1948, he made his true debut in a play called “The Druid’s Rest.” The following day he wrote to his beloved Sis. “Well,” he began this letter some- what jokingly, “I earned two pounds last night. So I guess that by the end of the week I shall have earned that ten I once spoke to you about. Perhaps even a little bit more than that.” Then, on the more serious side, he wrote, “it was really quite an evening. There I walked onto a stage in the West End and I knew, stomach full of butterflies, that among the thousand anonymous faces, were world-famous critics. I am happy that early this morning I read all the newspapers, and that these critics say that I am good enough to go on being a professional actor.”

There were other plays for Richard Burton in the year that followed: “Castle Anna,” “Captain Brassbound’s Conversion,” “The Boy With A Cart.” There was film work too, early in 1949—a lead in a picture called “The Last Days of Dolwyn.” It was, in fact, while Richard was making this film that he wrote another letter back home. And ended it with this notation: “Sis—there is a girl I have met. She is an actress, very fine. She is young and extremely pretty. She is Welsh—from Mountain Ash. Her father was a mine manager, a manger in the colliery, specifically, and so she is not too far removed from us in background and spirit. She is sweet, truly. I think that I am head over heels in love with her . . . Her name is Sybil . . .

Says Sis today—-seated in the den of her house on Baglan Road—of Richard and Sybil: “They were married very soon after they met. I couldn’t have been happier for my brother. For nowhere else could he have found a girl like Sybil. Nowhere. She is the most amazing girl. From the very beginning it never mattered to her what Richard did, or wanted to do— she would always say all right. Rich would leave for somewhere in the morning and say he’d be home for lunch. Perhaps he wouldn’t come home till late that evening. And Sybil would never chide him, the way most any other wife would do.

“I remember once I was with them and Richard came in at two o’clock in the morning. He said, ‘Do you know, Sybil, I’m hungry.’ And her only comment was, ‘What would you like, Rich?’ He told her. And there, at two o’clock in the morning, she popped into the kitchen to make a full meal for him. She understood him from the beginning. She loved him. I couldn’t have been happier when they married. Or chosen a better girl for him.”

Says Dillwyn Dummer, Richard’s cousin, of Sybil: “I first met her shortly after they were married. And I could see right off—she was a girl in a million. She is the homey type. The only people she thinks about are her own people—her husband, her children, her family. There’s never been a bit of the big-headed, the big-time stuff about her. She’s good as gold. And good for Richard. He was a pretty wild young man, after all. And Sybil cooled him down. Give Rich a pound back in those days and he’d spend two. It was the same with everything else about him. But Sybil, she cooled him down a fine bit. And don’t let anyone tell you that he didn’t love her right from the very beginning, that he didn’t appreciate her. I know. I used to see it. He’d come back to Port Talbot once in a while for a few days’ visit. And no sooner was he here than he’d be on the phone, talking to her all the time. He’d ask her to come join him these few days. He’d go wild if she explained that she was working in some play or was busy with chores, and couldn’t. And for a fellow to be like that—he’d have to have loved her a great deal, now wouldn’t he?”

Says someone who loathed Richard Burton: “He’s treated her shabbily from the day they met. He’s been rude to her. Unfaithful. He’s had girls from this end of the map to the other and back again. And still she stood for it from the beginning. Why? Well, Mephistopheles gets the best music to sing in ‘Faust,’ doesn’t he? Isn’t it ever the way for the poor, sad Marguerites of the world?”

Says someone who loves both Sybil and Richard: “She knew him for what he was the first moment she laid eyes on him. She loved him so much it couldn’t have mattered less to her whom else he went around with from time to time—or how he treated her. One of Sybil’s own favorite stories about Rich concerns the day they were married. The wedding ceremony took place at nine o’clock one morning. After a wedding breakfast, Sybil had to rush off to do a matinee. Richard and a brother of his stayed on at the flat to listen to a rugby match between Scotland and Wales. Was Sybil annoyed that her husband of a few hours didn’t accompany her to the theater? Not at all. Did she mind when, walking back into the flat after her matinee, Richard—despondent that Wales had lost the game—looked up at her and hollered, ‘Well, woman, what do you w ant?’ Not at all. In fact, she roared with laughter. After all, if she had wanted simply a conventional husband, she would have married someone else, now wouldn’t she?”

And so, at any rate, were Sybil and Richard Burton married on the morning of February 5, 1949. And so did the first twelve years of rather topsy-turvy happiness begin for them. Because they were happy years— 1949 to 1961. Richard earned a good deal of money. (He once said, amazed, “Just think of it. but for this film alone I‘m earning more money than my family did in 400 years!”) He shared much of that money with his family. (Says Sis: “He is the most generous boy alive. He has given all of us, his brothers and sisters, things we thought we would never see.” Says cousin Dillwyn: “You can’t shake hands with him to say goodbye that you don*t find a fiver for you where his hand was a moment before.”)

He bought himself, among other cars, the Rolls-Royce he once dreamed of. (A favorite story in Taibach concerns the time Richard showed the handsome gray automobile to his nearsighted dad. Dutifully, they say. Old Dick got up from his chair, looked through the window at the Rolls outside. squinted and said: “You say that’s a car. Rich? It looks to me more like a bloody boat!”)

Two daughters were horn to him and Sybil. (Says a friend: “When he says their names—Kate and Jessica—they come out like sigh. He adores those children. He’s bathed them. fed them—adored them.”)

“I nearly died laughing”

Professionally for Richard (Sybil retired from theatrical work shortly after Kate’s birth)—the years were magnificent. artistically and financially speaking. There were more films. There was more stage work—including, in 1951, a triumphant debut with the old Vic Company as Hamlet, that Danish prince Rich had first gotten to know on that hill back in Taibach.

There was, in 1952, a trip to New York (scene of his old RAF pub-crawlings) with the Christopher Fry play “The Lady’s Not For Burning,” and an award for the most promising actor of the year on Broad- way. There were other honors. And the beginning of long friendships. (Such stalwarts of the British theater as Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, John Gielgud. Anthony Quayle—all different types—immediately took to the brilliant young actor from Wales.)

And parties, parties galore. (At one of these parties, in New York. Richard first met a gorgeous young American actress named Elizabeth Taylor. “Site was so beautiful,” he has said of her and that meeting. “that I nearly died laughing. ‘)

And then, inevitably, in 1953, came the offer from Hollywood. The lead in “The Robe,” the most expensive production of the year. Which Richard first turned down.

“I don’t want the Hollywood bit,” he said to a friend at the time, already using the patois of that town to the West. “I want to go back to London. And work on the stage. The stage is life. The rest—it’s all false. Dylan said it once. Dylan Thomas knew the truth of t his. Just last year, before he died, he wrote a poem. ‘Our Eunuch Dreams,’ he called it.”

And then Richard recited from the poem:

“In t his our age the gunman and his moll / Two one-dimensioned ghosts, love on a reel / Strange to our solid eye / And speak their midnight nothings as they swell/When cameras shut they hurry to their hole / Down in the yard of day / They dance between their arclamps and our skull / Impose their shots, showing the nights away / We watch the show of shadows kiss or kill / Flavoured of celluloid give love the lie.”

“No,” he said then. “No. No. I don’t want any part of it. All this. This Hollywood they offer me. . . . It’s London and my stage that I want.”

“But, Rich,” said the friend. “Don’t you see the way it works? You don’t get the plum stage parts any more—not even in London—unless you establish yourself as a cinema name too. Look at Larry. Look at Ralph. They’ve had to do it this way—haven’t they? And it must be the same with you. So go to Hollywood. Make the money and the name for yourself. And then come home in triumph.”

With this in mind, Richard finally accepted the offer to make “The Robe.”

Hollywood? Disappointing

Those first Hollywood years were a disappointment to him. Partly, there was the disappointment that he felt in himself—since he found himself growing fonder and fonder of the money he was earning, and accepting parts in pictures he didn’t really give a damn about.

Partly, too, it was an egocentric disappointment in the fact that—aside from “The Robe” and a picture called “My Cousin Rachel” (for which he was nominated for an Academy Award)—he was failing to cause much of a ripple among the fans, the top-flight producers, even among his colleagues. (Jean Simmons once said of Richard: “It’s strange, but he doesn’t have the appearance of a movie star. No one ever stops him to ask for an autograph.”)

And inside him now were planted, it seemed, the seeds of a yearning—a yearning not at all peculiar to most anybody in show business—a yearning to become what is known in the business as a top star, a world renowned personality.

Meanwhile, however, Burton worked away at whatever parts were given him.

The next few years passed. He returned to London from time to time to do a play. He visited Sis and Dillwyn and his other friends and family in Wales when he had a chance. His heart, in fact. was always close to his home.

In the summer of 1956. for instance, on hearing of the death of Dillwyn’s dad, he wrote—from Los Angeles—this letter to the widow Dummer:

“Dear Auntie Margaret Ann.

“This is a brief note to tell you how deeply I sympathise with you—I have just heard from Sis of Edwin’s passing. There is no need for me to tell you how very fond I was of him; he was such a kind and generous man always, and he was always | so good to me when I was a little boy. We will all miss him very much. Tell Dillwyn. who is like my brother, that he has a mother’s sorrow and sympathy—I’ve thought of you all so much in the last two or three months because I knew in my heart that Edwin wouldn’t last the year. Don’t bother to reply to this. If you need anything let me know at once. Sybil sends her sympathy and love. As ever and in deep sympathy, Richie.”

Then a few more years passed. And then, in 1959, came the first of the two great offers of Richard Burton’s career.

The first was the offer to play King Arthur in the Broadway musical by Lerner and Lowe: “Camelot.” Which he did play, magnificently. Thanks to his own great (lair for this kind of regal role. Thanks too, to his old schoolmaster at Dyffryn Grammar—P.H. Burton—who had also come to the States by this time and who had taken over the reins of the show when Moss Hart, the musical’s original director, was taken seriously ill during out-of-town tryouts.

The second great offer, which came about a year after the opening of “Camelot,” was the role of Marc Antony in the picture they were planning, “Cleopatra.”

The great goodbye

The night was September 16, 1961. The place: the Majestic Theater on New York’s West 44th Street.

Richard Burton played his last performance in “Camelot” that night. When the curtain was rung up for his solo bow, the audience went wild. They clapped. They cheered. Whistled. Some cried. Some rushed to the stage and reached over the footlights to touch the robe Burton was wearing.

At a backstage party following the show, every big name in New York theater cireles was there to congratulate him and wish him well in Rome, with “Cleopatra.”

Richard thanked t hem all. made his usual jokes, kept pouring the champagne . . . and “thanks, thanks, thanks,” he said.

But to one of the well-wishers. towards the end of the party, he said these words:

“This is the big chance of my life, you know. The entire future of Richard Burton depends 011 what happens from here. They have to talk about me now. Else all is for nothing.”

The day was September 17, 1961 . . . the following day. The place: the so-called celebrities’ lounge at New York’s Idle-wild International Airport.

Richard, a little bleary-eyed from the farewell party the night before, stood in the center of the lounge—scotch and water in hand, Sybil and his two daughters at his side—while photographers snapped their pictures and reporters asked their questions.

“Are you excited about going to Italy. Mr. Burton?” asked one reporter.

“Of course I am.” said Richard. “I love the place. The Italians are like the Welsh. Their hearts are on their sleeves. They love to sing. They are all friends.”

Another reporter asked then: “How do you feel about playing Marc Antony, Mr. Burton?”

“Great. just great,” said Richard. “I know I’m going to feel just right in the part. He was the right kind, that Roman. Something like us Welsh. If he had to fight and labor, well, he did. But he also liked to have fun, to drink, to give banquets. Life is a big wonderful thing, isn’t it?”

“Mr. Burton—” a third reporter asked. “how do you feel about playing opposite Elizabeth Taylor in this picture?”

There was a small bit of a silence.

Richard took a sip of his scotch. And he smiled a bit on that one.

“Liz?” he said then. “A-ha. I hope you’re not trying to trick me with a question like that.”

He laughed.

Everybody laughed.

“But seriously,” he went on to say. “I have known Liz Taylor for twelve years at least. Delightful. But you have to be careful. There are a lot of people around her and they will jump on you. And. also, I realize that it is a little ridiculous to say of Liz that ‘she is a dear friend of mine. We know one another, let’s say. And we respect one another. And we will. I’m sure, find it very interesting to play opposite one another.”

A few minutes later, the interview was over. Richard took Sybil’s hand. And. with their children. they prepared to board the jet for Rome.

The rest, of course. is history of a sort.

—ED DEBLASIO

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1963

AUDIO BOOK