Marilyn At The Crossroads

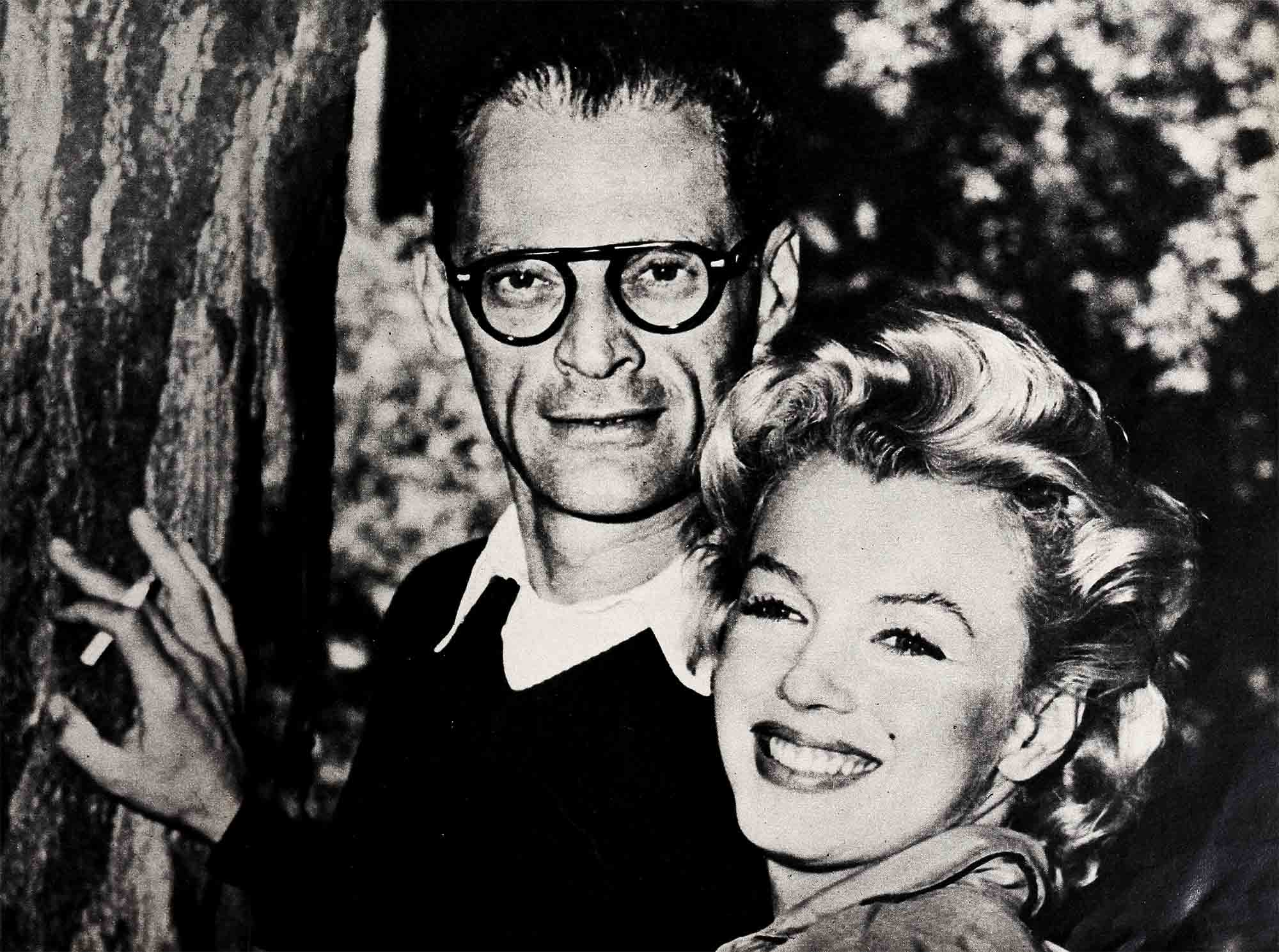

Few people, strolling along Fifth Avenue on a balmy spring day, noticed the couple—the spare, spectacled man taking long, brisk strides, the girl trotting fast to keep up with him, her face turned toward him, smiling and adoring. A few did a double take when they glanced at the girl—because she was wearing a mink coat that flopped around her ankles—and galoshes! Her blonde hair hung about her face in lank strands, and not even a trace of lipstick livened her pale features.

Marilyn Monroe didn’t give a hang that the crowds who would have mobbed her a short time ago didn’t gather. That Marilyn—the one who carefully displayed her charms in tight-fitting dresses in public and kept even a lone interviewer waiting for hours while she applied and reapplied her make-up before she could get up courage to see him—that Marilyn was gone forever.

She didn’t need her anymore. “Everything I ever needed or wanted in my whole life, I have,” she thought, gazing fondly at her husband, “Except the baby, of course. Then it will be perfect!” Her blue eyes filled with the tears that always come when she’s especially happy.

Arthur Miller pressed her hand. But he wasn’t smiling. What concerned him at the moment gave him no reason to smile. On May 13th, he had to go to court, to answer two charges for contempt of Congress, a result of his refusal to name names when he appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities last June even though he did not invoke the Fifth Amendment and denied that he had ever been a Communist.

To the newsmen who asked him whether Marilyn was upset by this when the charges were first announced, Arthur had replied crisply, “Nobody is exactly overjoyed.” But if Marilyn was upset then, she wasn’t now. She was prepared to follow her husband along Fifth Avenue, to the ends of the earth—or to jail, if need be.

Or was she? Can Marilyn Monroe really turn her back on stardom, with all its ego-swelling wealth and adulation and security? It is a decision she will have to make now. She is at another crossroads in her life—and time to decide on a turning is running short.

She has arrived at this point during the past year, by another of the puzzling personal revolts that have marked her behavior in the past.

At the beginning of 1956, Marilyn never had it so good. By holdout tactics, possibly picked up from baseball’s Joe DiMaggio, she had brought mighty 20th Century-Fox to its knees, winning a fat new contract that permitted her to select her own films and directors and gave her the right to make films elsewhere. If there were any skeptical souls left who scoffed at her yearnings for better things, they got their comeuppance when, in February, Marilyn announced that she would co-star in “The Prince and the Showgirl” with Sir Laurence Olivier, no less. But the skeptics held their stand, refusing to acknowledge that Marilyn had anything to do with it and gave credit for the coup to her manager, partner and guiding mentor, the everpresent photographer, Milton Greene.

Enter Arthur Miller. He stole into the picture discreetly, via bicycling dates with Marilyn in Brooklyn and cozy dinners at little out-of-the-way restaurants where the lights were dim and newshawks nonexistent. And he claimed Marilyn’s heart so completely that soon her former whole-souled affections for Lee Strasberg, director of Actors Studio, and his wife, Paula, Milton Greene and his wife, Amy, were getting second priority.

In the little frame house in Flatbush where Arthur’s parents, Augusta and Isadore Miller, lived—an exact counterpart of the one in their son’s greatest play, “Death of a Salesman”—she found warmth and love. Dostoevski and “The Brothers Karamazov” forgotten, she prattled with Mother Miller about Arthur’s favorite dishes and learned to make stuffed cabbage. And in June, in both a civil and Jewish religious ceremony, Marilyn and Arthur were married.

But she couldn’t go back to making stuffed cabbage for Arthur. She had to make a picture with Sir Laurence Olivier. So—after some difficulty in obtaining Arthur’s passport because of the Congressional charges against him—they set out on a venture that could have put the wackiest comedy script to-shame. At her first press conference, there was such a riot that both Millers and Oliviers had to barricade themselves behind a snack bar. Grave poetess Edith Sitwell, sipping gin and grape juice with Marilyn and Arthur, pronounced her “a remarkable woman,” while an English lady journalist wrote, “The most prominent thing about her is her spare tire.” Finally, to escape pursuit, Marilyn hid in a hearselike limousine—which only gave rise to further cracks about “the body” within.

On the “Prince and the Showgirl” set, things were scarcely less hectic. The first kiss of Marilyn and Sir Laurence was reported to “last all day.” But the sweetness and light did not prevail. In short order, there were stories about sharp disagreements. Said Marilyn icily when the cameras finally ground to a halt, “There were no more rows than the usual disagreements in making any film.” Said the gallant Sir Laurence, “Miss Monroe is a fine actress. She lived up to my expectations completely.”

Through it all, Arthur Miller strode stoically, and Marilyn went right on reap- ing a crop of headlines that exceeded a press agent’s wildest dreams—which continued when she returned, with the rumor that she was expecting a baby. “No comment,” said Arthur drily. “Some things,” cried Marilyn, “should be private.” On this slim shred, stories appeared that described Marilyn’s emotions, even her visit to an obstetrician, in great detail—stories that had not a word of corroboration from the Millers themselves.

All these shenanigans disguised some changes in Marilyn that were far more significant. Suddenly under Arthur’s tutelage, her attitude toward her career was switched. She shocked old business associates by turning up for conferences demurely dressed—and on time. She shocked them further by listening attentively, and making decisions with shrewdness and authority they never suspected she had. And she wouldn’t lift a finger to make a film. When MGM announced plans to make “The Brothers Karamazov,” her cherished dream, she didn’t even put up a fight for it.

Those who knew her well opined that Arthur Miller had become Marilyn’s Svengali, and she was letting her career go to pot.

One person who might well share these sentiments is ex-Svengali Milton Greene. She upped and gave him his walking papers, Greene countered by seeing lawyers. “I don’t want to do anything to hurt her career,” he said, “But I did devote about a year and a half exclusively to her, and practically gave up photography.” Snapped Marilyn, “He knows perfectly well that we have been at odds for a year and a half, and he knows why. My company has been completely mismanaged by Greene. He made secret commitments without informing me. He has misinformed me about certain contracts.”

Puffing thoughtfully at his expensive cigar, a 20th Century-Fox executive merely shrugs. There was a time when the problems of Marilyn were enough to make him take to Miltown, but no more. Now, he only says, resigned, “That girl had better come to her senses.” It isn’t a threat. He’s thinking about the days when Marilyn’s name meant millions to the studio. He’s thinking, in particular, about “Bus Stop.” It was a fine picture that won critical acclaim for all—including Marilyn. At the box office, it did well enough, but in comparison with her previous films, it laid an egg. The name Monroe wasn’t magic any more.

A cynical intimate of Marilyn’s also takes a dim view: “Arthur Miller is just another prop. First, it was her agent, Johnny Hyde. Then, when he died, it was Natasha Lytess, her drama coach. While she was married to Joe DiMaggio, she was torn between the two of them, and there was no love lost between Natasha and Joe. Then, she threw them both over and took up with Milton Greene and the Strasbergs at the Actors Studio. And now, Miller. I’m wondering if she really knows what she wants?”

To the lonely orphan girl, all the people named were, she thought, fulfillments in her lifelong search for the love and security she had never known. Parent ae Fathers and mothers she never had.

The one who was closest of all—closer than even Arthur Miller, because she was a woman, receiving confidences that one woman only gives to another—is Natasha Lytess. And strangely, it is Natasha, another outcast, who holds the greatest hope for Marilyn’s future happiness with Arthur Miller.

“Oh yes, I think it will last,” she exclaims, her brown eyes snapping. “I hope so. I give her my blessings. He’s a talented man. He has a good deal to offer. It should work, my heavens! He’s a far cry from that other guy!”

Natasha is just as positive that Arthur Miller is right for Marilyn as she was that Joe DiMaggio was wrong for her. In the spacious living room of her charming one-story white brick French Provincial home in Beverly Hills, Nathasha smiled wryly as she sat, legs crossed, in a comfortable club chair. A shaft of sun lighted her prematurely gray hair.

“I was always her bad conscience,” she said. “I raised her like a child. I’m thirty-six, only six years older than she, but I always felt sixty years older.”

“She knew she could come to me,” Natasha continued softly in her faintly Germanic accent. “She had a friend in me, and I say it very humbly.”

The living room was alive with subtle reminders of Marilyn, and bespoke her first exposure, under Natasha’s guidance, to the world of culture. It was Natasha who introduced her to art, good books, good music and good taste.

Classic-crowded bookshelves flanked the fireplace before which Marilyn so often had curled up on the rug. Those books were like chapters in Marilyn’s life. “The Brothers Karamazov,” a copy of “All My Sons” by one Arthur Miller, a book called “Wisdom of the Sands” by French author Antoine de Saint-Exupery, a gift from Marilyn which she had feelingly inscribed, “Because I met you, I’m learning.”

There were no visual reminders of Marilyn. “I never got an autographed picture,” Natasha explained sheepishly. “We were so close. It seemed so silly.”

Her eyes sparkled as she told the true story of Marilyn’s romance with Arthur Miller. They met during the year Marilyn and Natasha shared a two-bedroom apartment on North Harper Street in Hollywood. Miller had come to Hollywood to discuss a deal with Columbia which didn’t materialize. But a friendship with Marilyn did. She met him at a cocktail party.

“She fell in love with him then,” Natasha declares. “Nothing ever happened, but she told me excitedly that this was the kind of man she could love.”

They met several more times in the company of mutual friends, and Marilyn’s infatuation seemed to possess her. She told Natasha that she’s heard Arthur’s marriage to the former Mary Slattery was foundering, then in the same breath she’d add disconsolately that he’d probably stay married for the sake of his two children.

“The love was repressed,” Natasha went on. “You don’t go on suffering. She met DiMaggio and married him. But I knew all along she had the feeling for Miller. I used to tell her, ‘If it’s meant for you, Marilyn, it will come.’ And when it happened, I knew it was meant for her. I think she’s unspeakably happy. Now she has fame, money and the love of her life. It’s frightening.”

But what of the problems? Miller’s indictment for contempt of Congress? “If she loves him,” Natasha said quietly, “I think a woman can go through anything with a man. I think she loves him that much now.”

And what of a baby? Smiling, Natasha fingered a simple silver chain around her neck. “I had a talisman to bless me and my daughter,” she explained. “A very old silver medal with a figure of the Christ Child on it. When Marilyn had to be operated on several years ago for appendicitis, the doctors feared her fallopian tubes would have to be removed. Marilyn was so distressed at the thought that she might never be able to have a child, and on the day she was to be operated on, I gave the talisman to her.”

During the operation, Marilyn clutched it in her hand. When she left the operat- ing table, she was still able to bear children. The fear that her fallopian tubes might be infected proved to be unfounded.

“She wore the talisman for a long time after that,” Natasha smiled, “On a silver chain around her neck.” She always wanted to find a man she loved, and have a child.

Yet Natasha has one reservation about marriage that stems from her first meeting with Marilyn, back in 1947. She was an unknown starlet named Norma Jean Dougherty then, sent by Max Arnow of Columbia with the hope that Natasha could “do something with her.”

“She wore a red knitted dress and her hair was disheveled,” recalls Natasha. “She looked just like lots of little girls who come to me. What struck me was that she was very, very closed. She was so much in a shell, she couldn’t talk. She was very, very unhappy. I felt she had a dire need of what I had to offer.”

Natasha beseeched her to stop tormenting herself with childhood hangovers. “Let it dry up,” she begged her. “Stop milking it. Otherwise you’ll never be the master of it, always the victim. Come one day to the point where you are grateful for every misery you had, every foster home. Come to the point where you realize your mother and father didn’t know what they were doing, so you won’t have that bitterness. Don’t drown in self pity.”

One day, a troubled Marilyn came to her and confessed, “I’ve posed in the nude.” Natasha told her, “Marilyn, it’s done, so forget it. But don’t do it again.” Later, when the news came out, she was terrified. Natasha said, “For goodness sakes, Marilyn forget it. People aren’t that interested in anything. Headlines come. They read them and throw them in the ashcan.” Marilyn felt reassured, and was able to tell the truth about it.

Natasha frowned. “But she is still so terribly insecure. That’s dangerous. With an insecure person, you don’t dare be strong. Then. you carry them, and it inhibits them even more. This is definitely true of Marilyn. You have to be very delicate. She’s always on the defensive.”

Is Arthur Miller the person to keep that delicate balance? “Often, artists are people who can’t live what they paint or write,” Natasha mused. “If Miller lives what he writes, I say fine. But I don’t know.”

Does Marilyn? Maybe. Maybe not. But at the moment, there are strong indications that she has at last found the security she has longed for.

For the first time in her life, she has the courage to go without makeup, and dress as she pleases. She isn’t “letting herself go,” as some think. For her, this is a new kind of freedom—freedom from the bondage of her body. For years, she thought that her figure and her looks were all she had. Now, she doesn’t.

Her tardiness is a thing of the past, not because Arthur Miller has goaded his wife into promptness, but because she is no longer afraid to meet people, forever stalling the fearful moment when she would have to come face-to-face with them, be- cause for too long all people were strangers.

She is no longer afraid to speak her mind. She can make her own decisions, because she has gained self-respect.

So strong is her faith in herself and in her husband that she stood staunchly by him in the face of the Congressional contempt charges. An M-G-M executive revealed that one reason she gave the studio for turning them down when they approached her about “The Brothers Karamazov” was that she wanted to be near her husband during his trial. The other reason: Marilyn told them that she was expecting a baby.

So, above all, she gained confidence—enough to put one of the most valuable careers in the world second, and marriage and motherhood first.

It looks as if Marilyn Monroe is going to take the right turn—to happiness.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1957