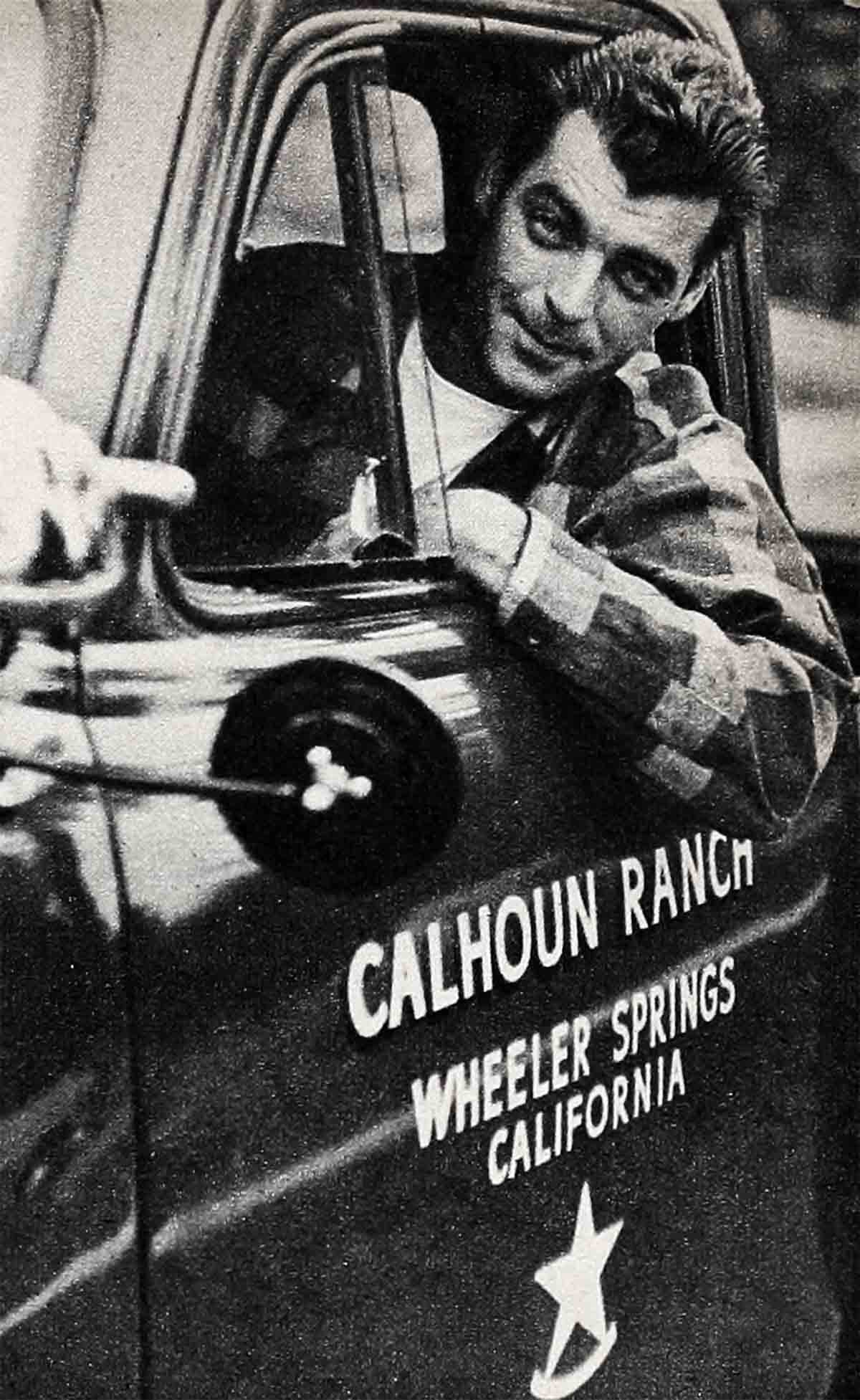

That Crackerjack-Of-All-Trades, Rory Calhoun

The postal clerk at the little town of Ojai looked up in surprise at the tall, handsome, dark-haired young man with prematurely grey temples. “You sure you know what you’re doin’, young fella?”

Rory Calhoun’s voice left no doubt. “Positively!”

“But this letter you want me to register— it’s addressed to yourself.”

“I just wanted to make certain . . .”

He didn’t tell him certain of what, or he might have given away a secret that had to be protected at least till it was securely registered with the United States Patent Office. By the cancelled postmark on the unopened letter, Rory could prove, if necessary, just when he first had the idea. You see, in addition to being an actor, rancher, saloon keeper, builder and jack-of-all-trades, Rory is also an inventor of some repute. You’ll be even more surprised about some of the things Rory has invented!

The contents of this particular package dated back to a camping trip a few weeks earlier, when Rory got up at sunrise to fix breakfast while his pretty wife Lita was still curled up in a sleeping bag, hoping to get in a few more winks before an unquestionably exhausting day of hiking and fishing began.

Her sleep was soon interrupted, not only by the hickory aroma of coffee boiling over a crackling fire, but also by Rory’s disgusted, not exactly drawing-room-type outburst about the eggs he had fried.

Sleepily she stuck her head out from underneath her warm, woolen blanket. “What’s the matter, darling? Are you having trouble?”

“Trouble? I do a perfectly good job of frying eggs till they’re just right, and when I try to get them off the spatula, the yokes break and the whites flow all over the plate.”

“Don’t worry, darling. It happens to the best of us.”

That settled it for Lita—but not for Rory.

He kept thinking. Finally he came up with the answer: a spatula with a pusher attached to the handle which slides off an egg so gently, even the hen couldn’t object!

Having a business mind as well as being inventive, Rory had no intention of keeping the idea just for his own use. He planned to have it patented, and someday, quite possibly, make as much or more money from his royalties than he earns in the movies.

He proceeded about it carefully, because a few years ago he failed to protect another original idea which was promptly stolen. And Rory isn’t the kind of fellow who gets burned twice.

That time he’d invented the first detergent cheesecloth, which might have made him a millionaire had he not talked about it before it was securely protected.

It would take too many pages to list all of Rory’s original ideas, but there’s at least one more which deserves mention, because in the years to come it might ease the burden of farmers all over the world.

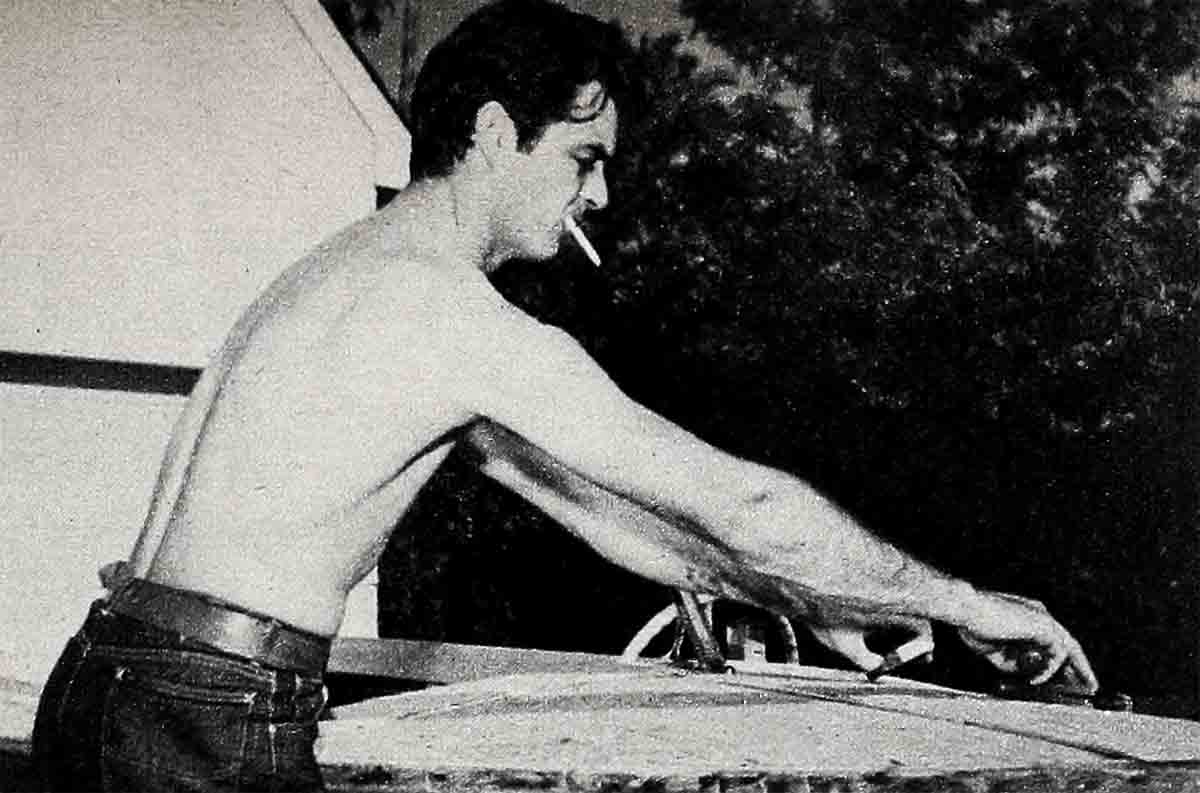

Irrigation has always been one of Rory’s biggest headaches on his ranch. With comparatively little rainfall, not much will grow without it, yet it’s a backbreaking job to constantly move irrigation pipes through which the water must flow.

One evening, so tired he could hardly stay awake through dinner, a thought occurred to him that solved his problem: Why not put wheels on the pipes, and roll them from place to place instead of carrying them?

Put into practice, it proved a practical time and energy-saving device which today is being used by an ever-increasing number of ranchers.

Not only his ingenuity but a number of other revelations about Rory may come as a complete surprise to his many fans who are comparatively unfamiliar with Rory’s life—in spite of the thousands of words that have appeared about him.

The reason? Unless pressed, he’s not particularly fond of talking about himself. He feels that what he’s doing away from the camera is his own business.

To this, add the fact that his handful of close friends—Howard Hill, Guy Madison, his foreman Eddie Sandlin, West Christiansen and Hal Biller—can’t exactly be described as chatter boxes either! No wonder little is known about Rory except that he is happily married to Lita Baron, does well in pictures and is an expert hunter. Even on the latter subject there’s a great deal of misconception.

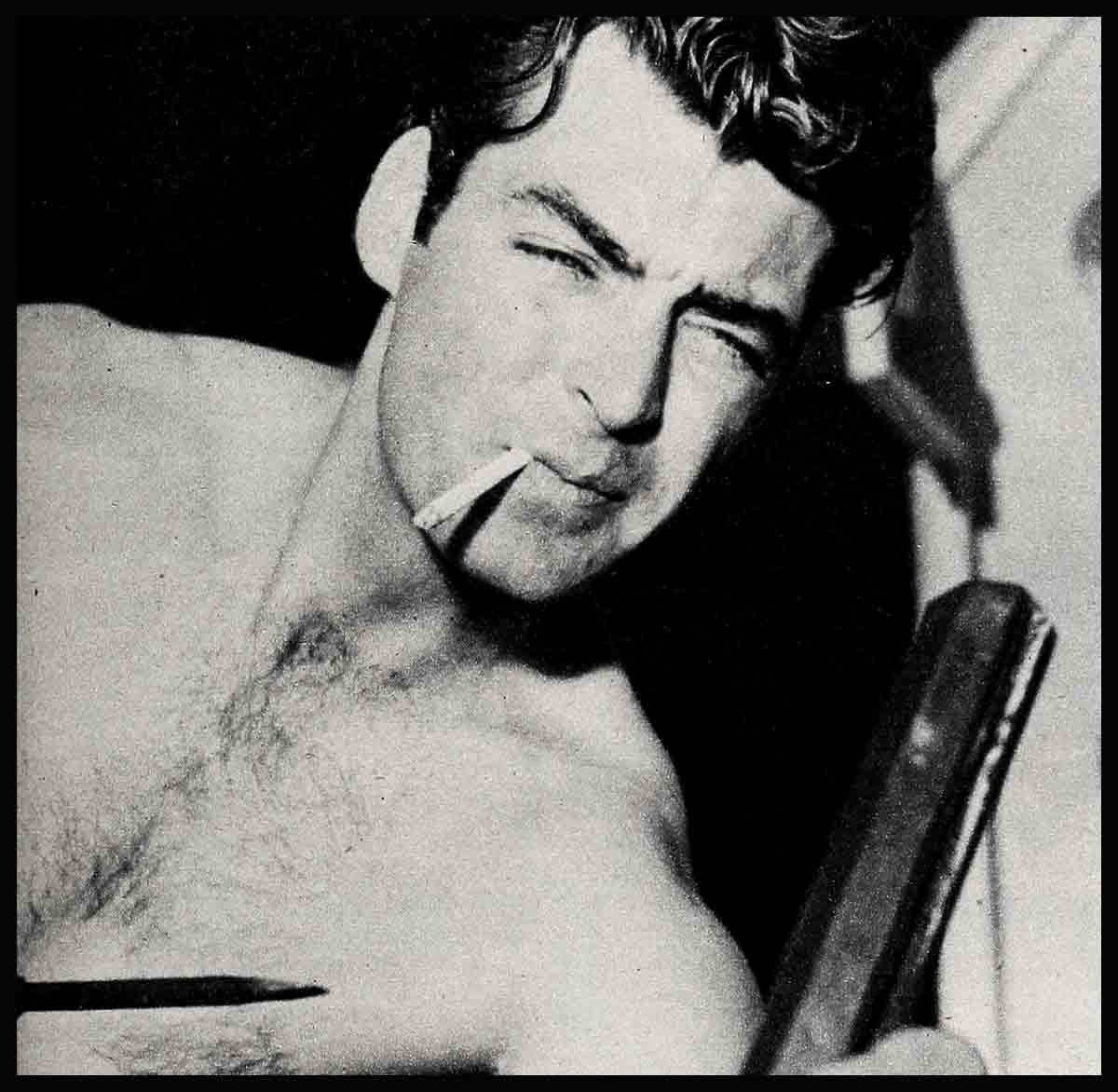

It is generally believed that Rory took up hunting with bow and arrow as a result of his association with the 20th century Robin Hoods, Howard Hill and Guy Madison. That’s not the case.

Actually, having used a .22 Winchester since his sixth birthday, he found hunting with a rifle somewhat dull. By the time he was fourteen, he exchanged it for a bow and arrow.

That doesn’t mean he has lost his taste for fire weapons altogether. He owns ten rifles and would have double that number if Lita wouldn’t protest so hard every time he brings another one home.

To the vast majority of Hollywood actors, a successful career is the ultimate goal. To Rory it’s just a means to an end, a way to make money to promote some of his other projects till they become self-supporting.

Because he has no illusions about his acting ability, he has sometimes angered his bosses with his attitude. At 20th Century-Fox, where he was under contract for many years, he refused to attend drama lessons, reasoning that it would be a waste of time, that he would do better simply being himself rather than try for a more polished, more dramatic but less convincing performance.

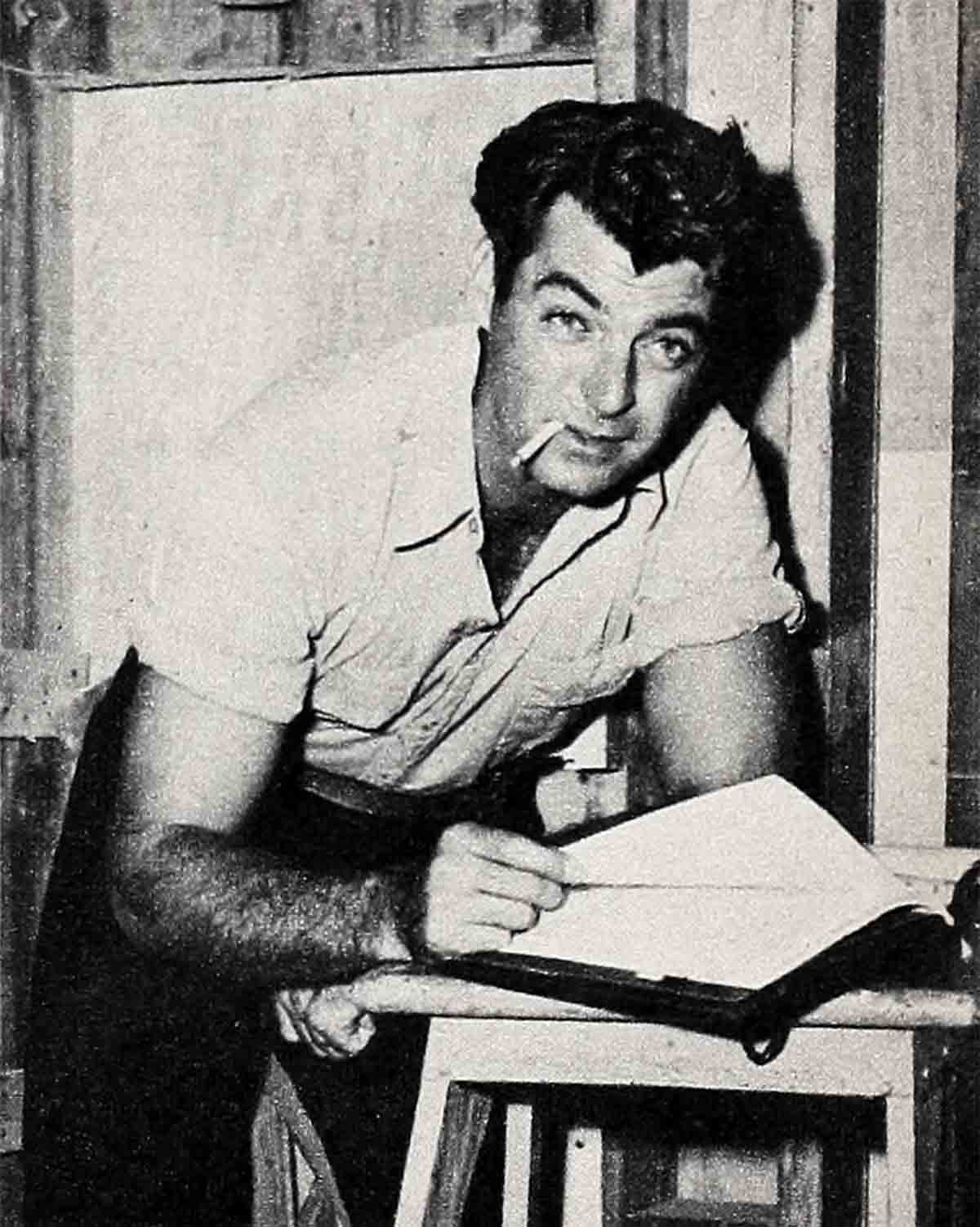

The fact that his acting is limited to playing himself on the screen doesn’t preclude a lack of creative spirit on his part. On the contrary: It’s one of his many ambitions to become a successful writer. He has already sold one original story, “Shot Gun,” which was made into a movie soon to be released, starring Sterling Hayden and Yvonne DeCarlo.

Hand in hand goes Rory’s hunger for reading, though his taste and manner of reading are quite astonishing. It ranges from the scientific to the ridiculous. He can get equally enthusiastic over technical analyses, Book-of-the-Month Club selections and the Sunday funnies. Because his biggest problem is time, he reads fast, like he’s worried he might miss out on something if he didn’t get through one book quickly enough to start another one right away. When he accompanied Lita to New York last summer, when she appeared at the St. Regis, he read five books on the train between Los Angeles and Grand Central Station in New York City—a train ride of a mere two days and three nights!

On Sunday morning, his favorite part of the paper is the Home Section. To get ideas for his house, which he and Lita keep redecorating.

For that matter, Rory has all kinds of unusual domestic qualities. He loves to cook, for instance.

This inclination has paid off handsomely in recent months, since Rory has become a restaurateur (“I’m not in the restaurant business,” he insists. “I own saloons, but the food is good!’’).

He first got the idea when he heard of a place for sale on highway 101, near Ventura. Food and drinks are basic commodities, he reasoned. If you give customers quality and service, you can’t fail.

He gave them both and did so well that three months later he opened his second “saloon” in Ojai, and soon a third, nearby. He now contemplates opening additional places in Fillmore and other Southern California localities. It won’t be surprising to anyone, least of all Rory, if within a few years, he’s running the biggest chain of restaurants—or whatever he calls them —in California.

Rory is not an absentee proprietor. Although he has full confidence in his brother-in-law, Pete Castro, who runs his chain, whenever he finds time he stops in at one of his places. And not just for a quick checkup, but to work.

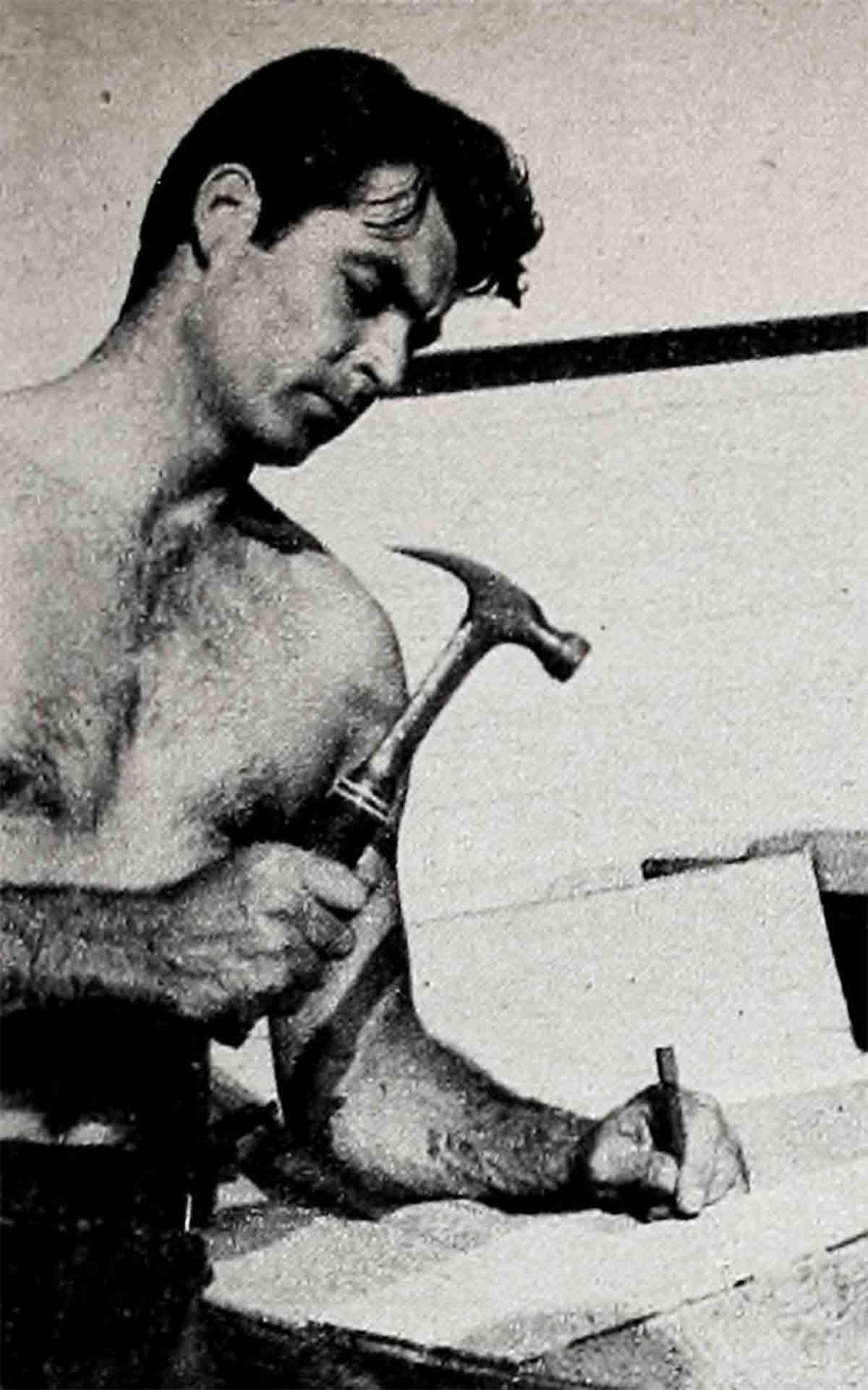

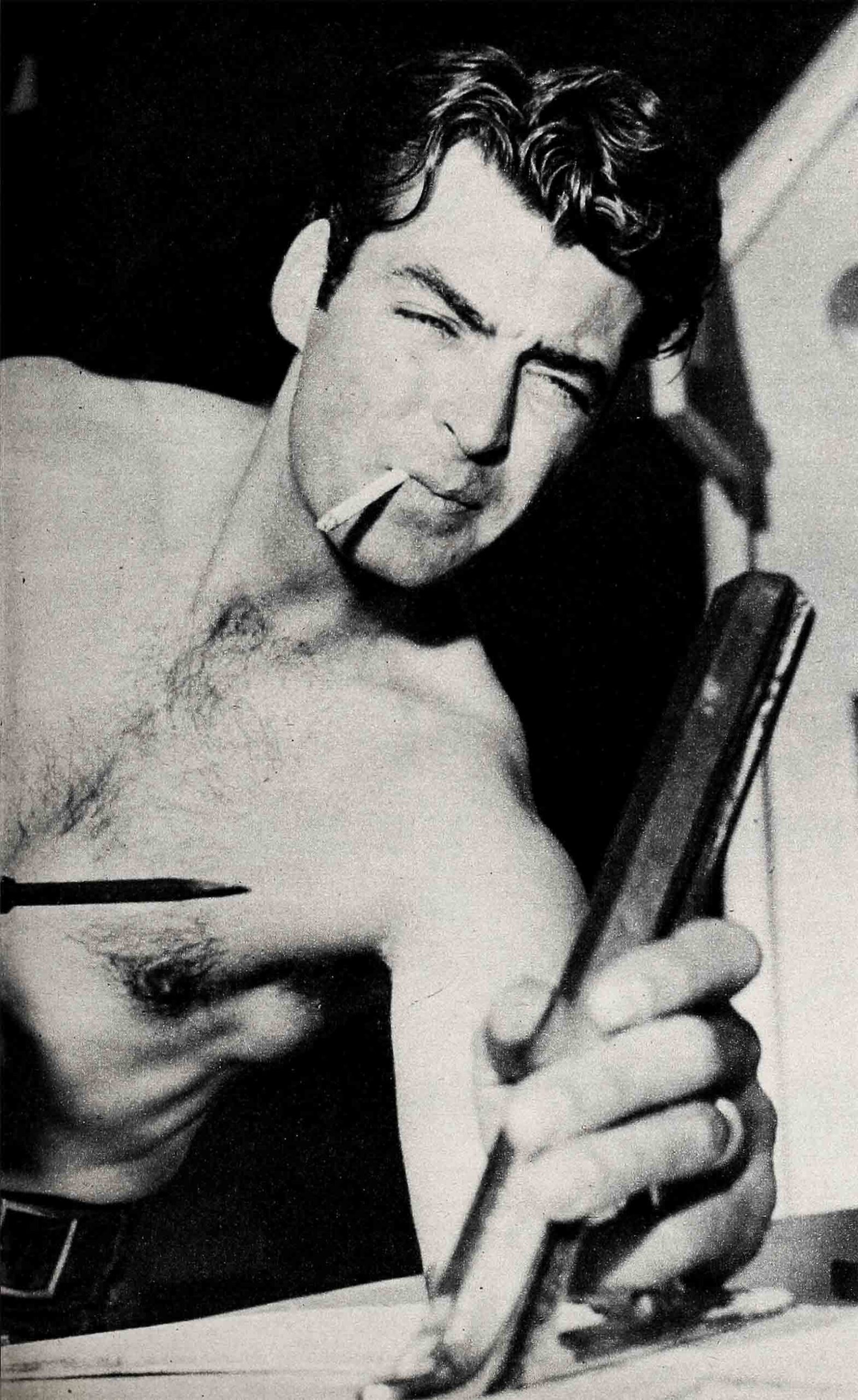

Many of his fans may wonder why a movie star like Rory—who could afford to hire manual laborers—himself does so much hard physical work.

He has two reasons: If something goes wrong, he has no one but himself to blame. Furthermore, working with his hands is so much a part of him that he can’t do without it, no matter how much money he’ll ever have in his bank account. It’s a physical kind of independence, a desire to get along without help, of being capable to do any job anyone else can do. Rory would have made a good pioneer.

He always has been a self-made person, anxious to work for his independence. He earned his first money when he was seven, dragging nets on and off fishing boats.

At ten he was making twenty-five cents an hour mowing lawns, and at fourteen was in business for himself: he had the lubrication concession at his father’s gas station, and by his own choosing, paid rent for it as any outsider would have to do. Averaging four dollars a day, a huge amount in those days for a boy his age, he not only saved enough to buy himself a ’32 “Model B” Ford during his junior year in high school, but on his insistence also paid for his clothing. Not that he was particularly fond of clothes—he never owned more than four suits at one time—but he wanted to prove, mostly to himself, that he could get along on his own. He’s been proving it ever since.

This attitude certainly comes in handy at the ranch—twelve miles from the nearest phone—where he is faced with constant emergencies. He has to be a combination electrician, plumber, carpenter.

In stories that have been done in the past about Rory and Lita, not enough credit has been given to the girl who has contributed so much to his success and happiness.

It was quite an accomplishment for the tiny, attractive singer to get adjusted to her husband’s kind of life: camping out, going hunting and fishing, taking care of a four-bedroom home in Beverly Hills, at the ranch doing all the cooking, cleaning, washing dishes, running the tractor, helping put up fences, sharing with Rory almost any other kind of manual labor. Yet she manages to keep up with her husband and still look as attractive today as she did in 1948 when Rory first heard her sing with Xavier Cugat and his band in the Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium.

A few weeks ago, the girl who six years ago didn’t know the difference between a Holstein and a Jersey cow, surprised even her husband with her ever-growing knowledge of ranching. Rory and Eddie Sandlin were discussing how to stock the ranch when she suddenly cut in with her ideas on the proper percentage of each type of cattle. What’s more, she justified her arguments by quoting the exact price of beef at the Los Angeles stock market.

Curiously, although Rory doesn’t object to her hard, physical work on the ranch, he considers her night-club appearances too strenuous for the remuneration. A top singer, says Rory, deserves a top salary, and hers, he feels, has never equalled her popularity with her audience.

Rory’s reasoning seems strangely contradictory—till you consider his own attitude in this respect: Because he works for himself, he doesn’t mind getting dead tired doing physical labor for which he could hire a man for $1.25 an hour. But for his films, he wants the best salary he can squeeze out of the studio. His present contracts are the envy of many equally successful actors who don’t have his business sense.

Thus, in a way, Rory has a double concept of life: On one side, get all you can out of it, financially. Keep busy with new enterprises. Don’t restrict yourself to one line of work. Expand constantly. On the other hand, don’t let financial and career success interfere with the basic things in life. For the only kind of life, according to Rory, worth living is a full, well-rounded, productive existence.

THE END

—BY PEER OPPENHEIMER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1955

No Comments