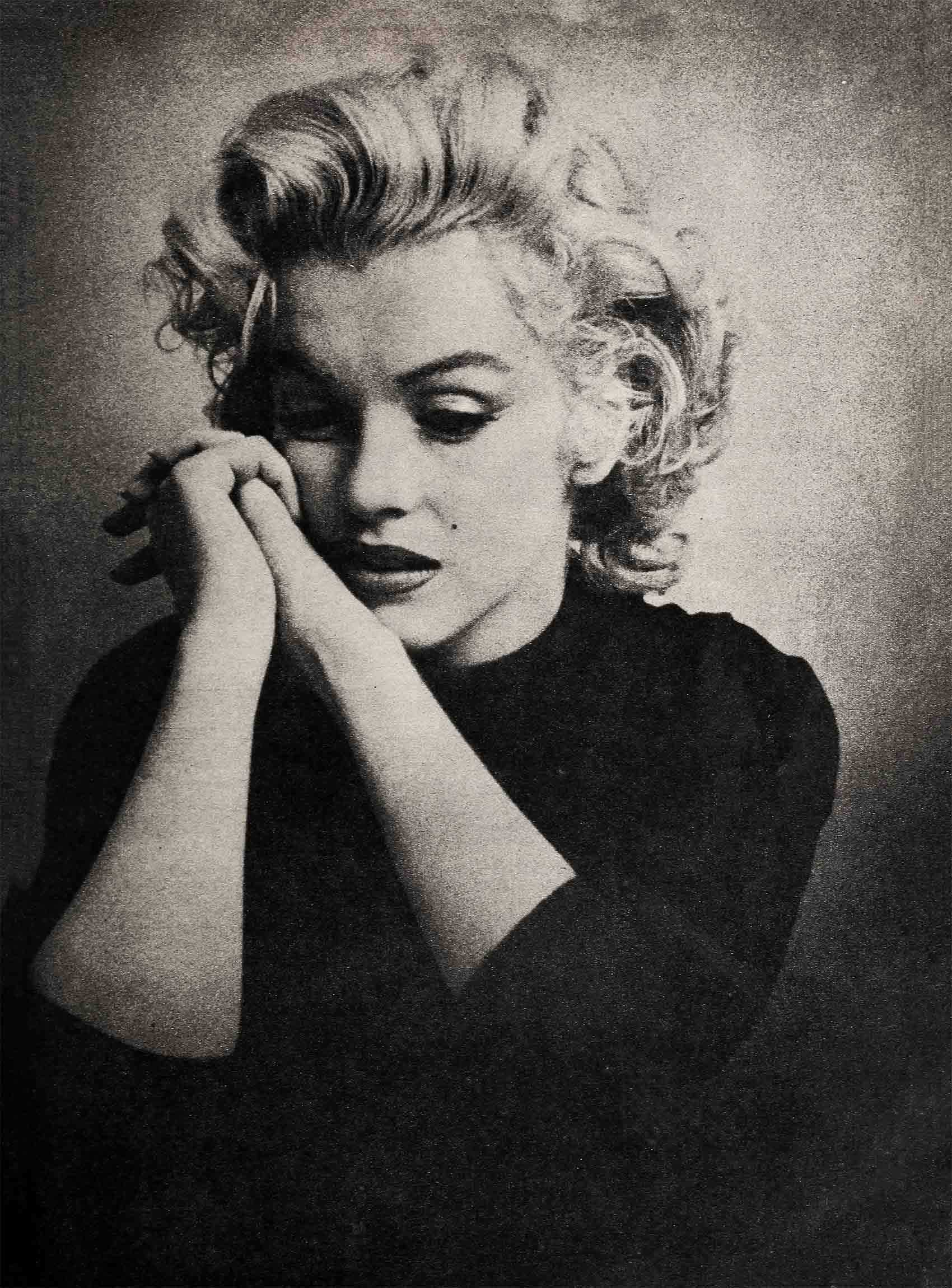

And The Lord Taketh Away—Marilyn Monroe

This is the story of a beautiful girl. And of a town. And of a baby.

The girl’s name is Marilyn Monroe. The town’s name is Amagansett. The baby will never have a name.

But for that little while it lived, deep inside its mother, it could have truly been called Love.

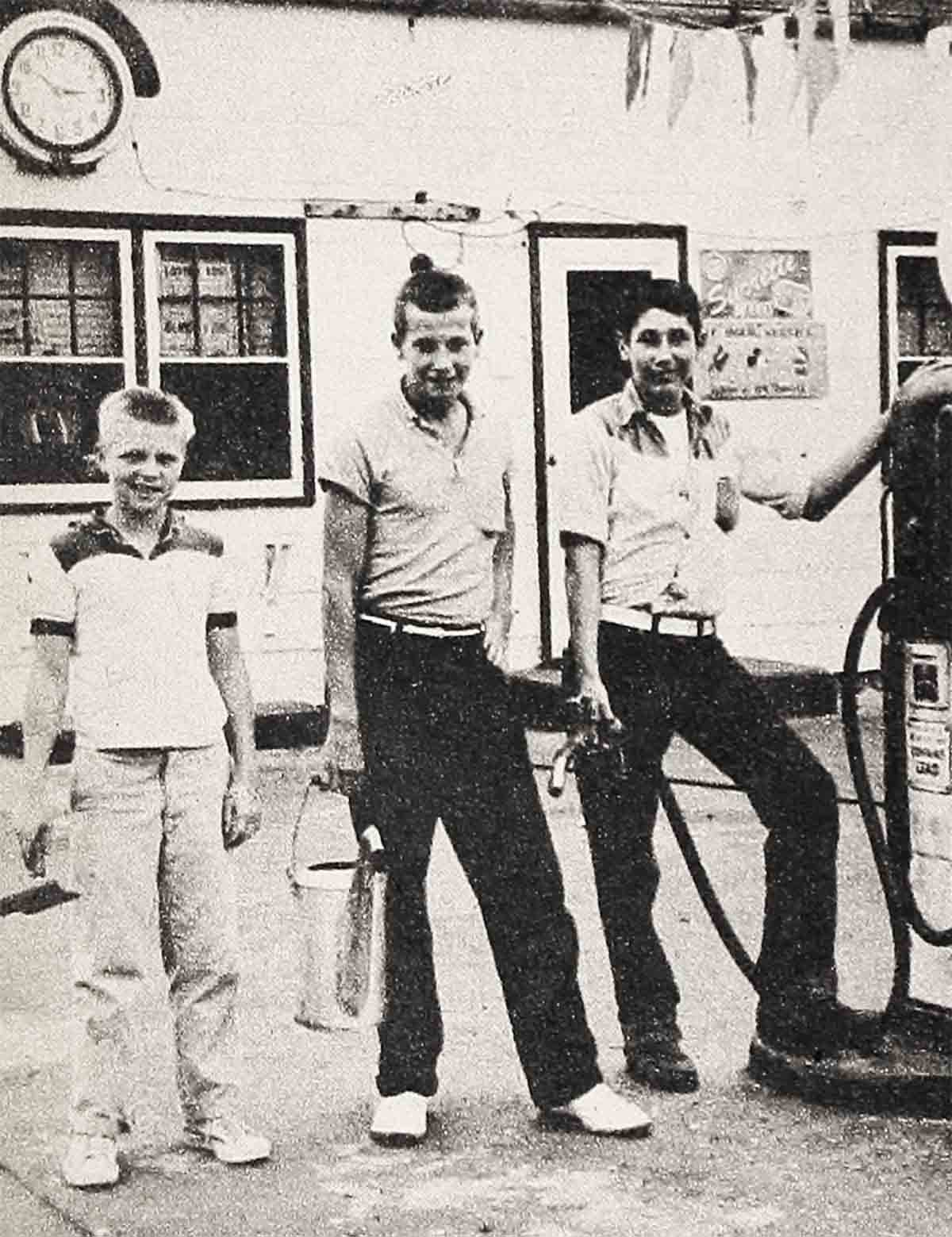

The story begins on a Thursday afternoon back in mid-June, when a big white Lincoln convertible pulled into Ed Raynor’s SINCLAIR gas station in Amagansett, a tiny town on Long Island’s south shore—at the very tip of New York. Raynor was away for a while and Johnny Cantwell, sixteen, was taking over the chores. With Johnny were his two pals and helpers, Eddy Loper, fifteen, and little Dicky Gosman, twelve.

“Fill ’er up?” Johnny asked the tall, thin man who was driving the Lincoln.

It was while the man behind the wheel was paying them that Johnny took a good long look at the blonde lady and said to her, “Criminellys . . . you’re Marilyn Monroe, aren’t you?”

Marilyn nodded.

“Criminellys!” all the boys repeated now, in chorus.

“Do you fellows live here in Amagansett?” the man sitting beside Marilyn asked, after he’d introduced himself as her husband, Arthur Miller.

Yes, the boys said, they did.

“Well,” said Arthur, “I guess that makes us neighbors. My wife and I are going to be living here in Amagansett this summer.”

“Miss Monroe,” Johnny asked next, “could you give us your autograph so we could show people so they’ll believe us?”

“Sure,” Marilyn smiled.

“You know, Miss Monroe, you’re my favorite actress,” Johnny said.

“Well, thank you,” Marilyn said, handing him the autograph.

“Mine, too,” Eddy chimed in.

“Thank you,” Marilyn said, and gave him his.

“You’re not my favorite,” little Dicky piped up. “I like you, all right. But I like Jayne Mansfield better.”

Marilyn and Arthur laughed so hard the three boys thought they would never stop. Then Marilyn signed Dicky’s little piece of dirty cardboard—the only thing he could find—and Arthur asked them how they could get to the beach.

When Ed Raynor, the service station owner, and his wife Stella drove up a few minutes later, the boys rushed up to their car.

“We just filled Marilyn Monroe up with gas,” little Dicky burst out.

“Yeah,” Eddy said, excitedly. “She was just here, her and her husband . . . And she wore a big red coat and I could see she was wearing tight black pants.”

“And when she opened the door once I could see she wasn’t wearing any shoes,” Eddy said.

“And her hair was very messed up,” little Dicky added. He squinted. “Do you believe us?”

these are Marilyn’s neighbors—the people of Amagansett—and this is how they feel about Marilyn . . .

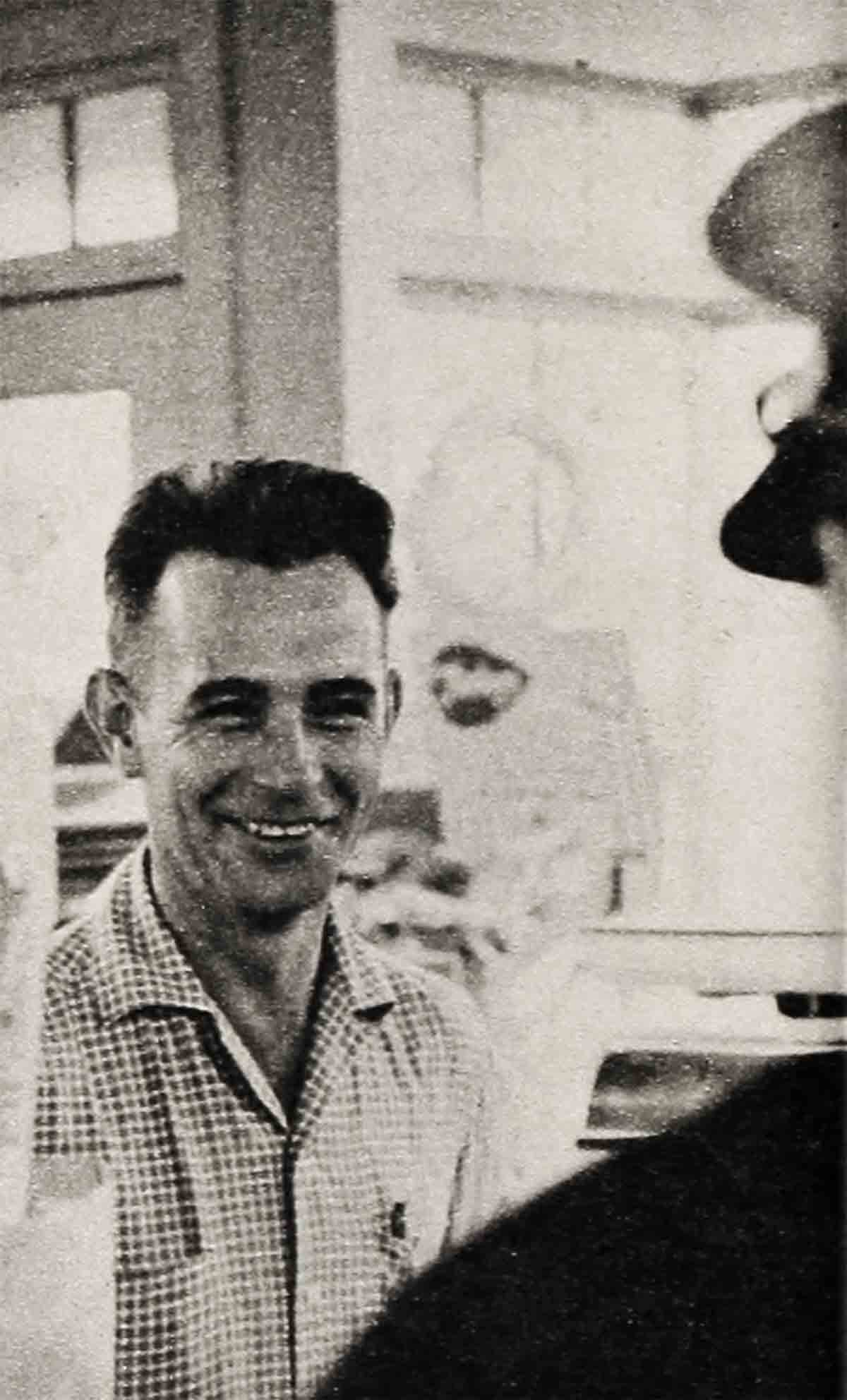

Bob Winslow is half owner of the grocery store where Marilyn shoppe And what does he say about her? “I got such a charge watching Marilyn cover every aisle—and did she load that shopping cart!”

Just like the other housewives

The Raynors looked at the autographs, then at each other. After lots of coaxing, they drove the boys to the beach for another look.

Yes, there was a Lincoln convertible parked there all right, with two people standing alongside it, looking out at the ocean. And when the blonde girl turned to say something to the man, there was no mistaking it—it was Marilyn Monroe.

Marilyn’s and Stella’s eyes met a moment later. Marilyn smiled and waved. Stella smiled and waved back and called out, “Welcome to Amagansett.”

Marilyn and Arthur walked over to the Raynor car. They introduced themselves and the two couples shook hands all the way around.

Then, after talking a little about lots of little things, Marilyn asked Stella if she knew whether TOPPING’S, the local grocery-butcher shop-and-soda fountain delivered. “We just got here and our cupboard looks like Mother Hubbard’s,” she said.

“Oh, sure they deliver,” Stella said. “Here—” She reached into her husband’s pocket for a pencil. “I’ll write down their number for you.”

Marilyn and Arthur thanked them very much and after a few more words they said goodbye and walked back to their car.

It was bright and early the next morning—about 8:15—when Bob O’Brien, the check-out clerk and delivery boy at TOPPING’S arrived at the cheery little house the Millers were renting on a piece of land known as Stony Hill Farm. Marilyn had phoned her order in the night before and Bob was lugging it to the door now and secretly hoping for a peek at the star.

He nearly fell over when the star herself came to the door.

“Hi,” he said. “I’m Bob O’Brien.”

“And I’m Mrs. Miller,” Marilyn said.

Then they began to talk, the big Hollywood actress and the happy delivery boy.

“Mrs. Miller,” Bob finally asked, “could I ask you a favor? I wonder if sometime before the summer’s over I can bring a camera and get somebody to take a picture of us together. It sure would be something for the fellows down at school to see.”

“I’ll be happy to do that,” Marilyn said.

“Oh boy,” Bob shouted, rushing off.

Marilyn drove up to Topprnc’s the next morning in her own ear, a black Thunderbird—no need, she’d decided, to phone her order in. Here in Amagansett I can just walk into the grocery and shop like all the other housewives do. . . .

For the next fifteen or twenty minutes, Marilyn happily roamed the store. And, slowly, her cart began to fill up with canned cherries and angel-food cake mix and a couple of different kinds of ice cream and “two pounds of ground beef . . . and a few lamb chops for tomorrow, and maybe some steaks. And can you cut the steaks thick, please? My husband likes them thick.”

And as she left, a couple more people standing around—not strangers suddenly, but neighbors and friends—stopped to say Hello . . . how are you? . . . Hello . . .

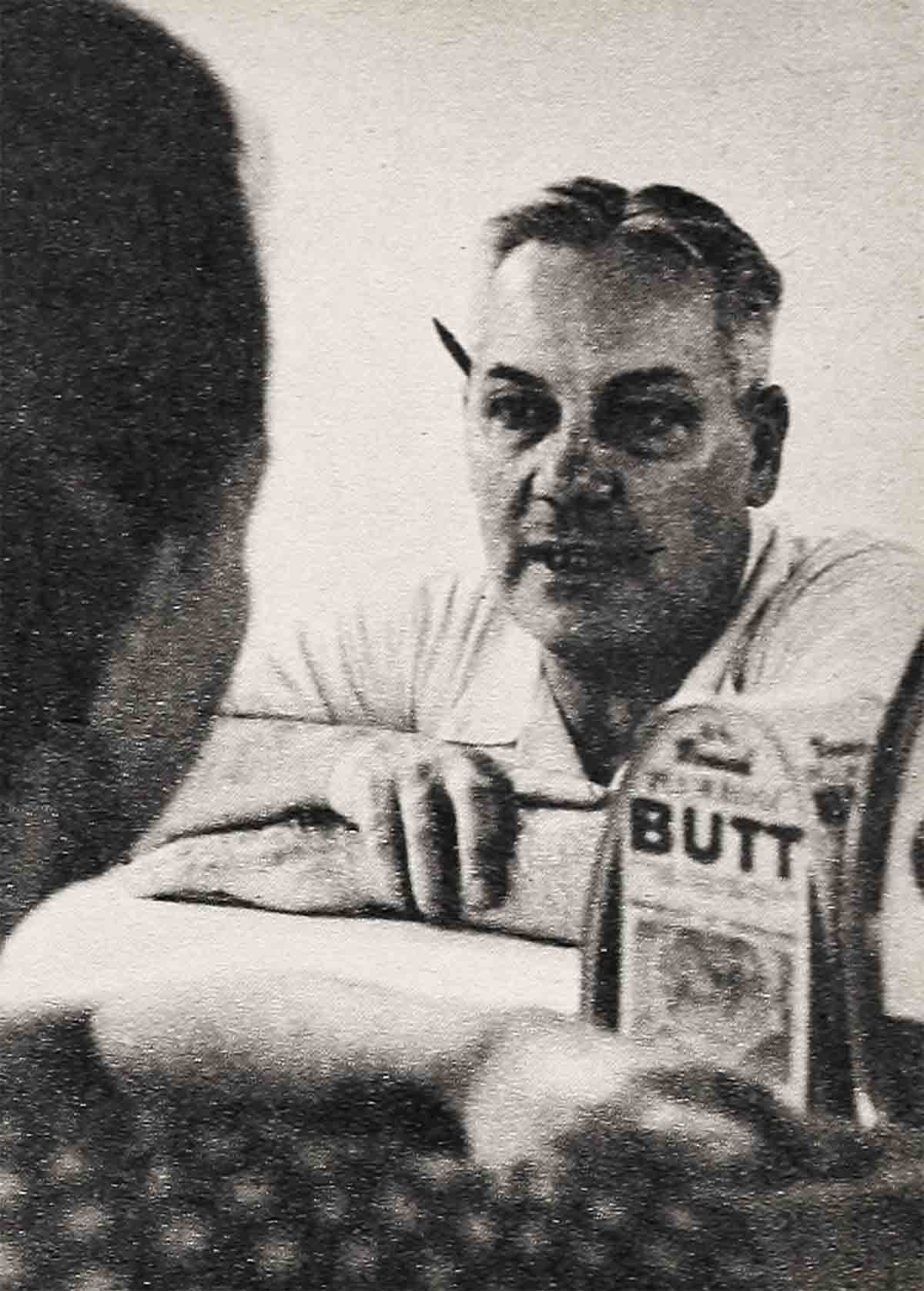

A man and his wife were the next to talk to Marilyn. The man was Roger Mattei, owner of THE CORSICAN RESTAURANT, just down the street. The woman was his wife, Helen.

“We’d love for you and Mr. Miller to come to our restaurant for dinner some night,” Helen told Marilyn.

“And,” Roger added, “don’t worry about maybe there not being something on the menu you like. I know that you like Lobster Monaco, stuffed with the clams and the shrimps, and that you like the sliced filet mignon Bordelaise, and I will prepare either of them for you any time you wish.”

Marilyn was amazed. “But how do you know. Mr. Mattei?” she asked.

Just like her own home town

The chef nodded wisely. “For many years,” he said, “I am a chef in New York and, of course, I know many other chefs and when I hear you are coming to Amagansett I telephone the chefs and I ask them what are your favorites. It is that simple. We always do that, when we can—mind out what our new neighbors here like to eat, just in case they become our customers!”

“Suddenly,” Marilyn said to Arthur, felling him about it later, “suddenly these people were my neighbors . . . and this, well, I felt as if this place was finally my home town. . . .”

The next six weeks were wonderful for Marilyn and Arthur and the neighbors of Amagansett.

“Practically every morning Marilyn and her husband came to the beach for about an hour,” one local boy said, “and they usually walked up a ways and they’d go surf-casting. Sometimes some out-of-owners would come and walk right by them and stand around for a while. But we could see it made them embarrassed and so when we saw them we’d just wave and they’d wave back and then they’d do their surf-casting.

A most wonderful six weeks

“Then in the afternoon—me and the other fellows could see all this from the firetower—in the afternoon, they’d sit around the garden. She’d always be dressed in shorts and be watering the garden or fixing some of the flowers up or something. And Mr. Miller would be dressed in shorts, too, but he’d usually be sitting reading a book. Or sometimes he’d bring a typewriter out and start typing away. And that’s the way it would be a lot of the time. Just the two of them together like that.

“And then other times, usually over the weekend, there’d be other people there with them to keep them company. Once an old couple came and it turned out to be Mr. Miller’s mother and father from Brooklyn. And then they came a few more times and always brought two children with them, a boy and a girl, who turned out to be Mr. Miller’s children by his first marriage. And that’s when it really looked like they were all having fun there—Mr. Miller playing catch with his son and Marilyn and Mr. Miller’s daughter and mother preparing a big cook-out with hot dogs and steaks and potato salad and some kind of cake Mr. Miller’s mother used to bring from Brooklyn, I think, because it was always in a pan and she always used to make Marilyn sniff it first and then her son before she cut it. . . .”

“At night,” remembers another Amagansite, a woman, “they usually stayed at home, just the two of them. Mrs. Miller prepared supper and did the dishes and acted just like any ordinary housewife around here. And sometimes—I know this for a fact. because my husband and I were doing the same thing once and saw them—they would get into their car at about 10 o’clock and drive to the ocean and take off their shoes and just walk along the beach. holding hands, close to the water, talking and laughing and then not talking and not laughing but just walking . . . well, again, just walking along like any other ordinary couple in love.”

Signs of something extraordinary

And, like any other ordinary married young woman in love, Marilyn gradually began to show signs of something both ordinary and extraordinary at the same time.

It showed first where it shows with all women—in their eyes, in the way their eyes seem a little larger than they’ve ever seemed before and more sparkling and wiser and happier.

And then it began to show, just a little, in her figure.

She was in the post office one day, mailing a letter she’d just written to Arthur’s children. when two old women walked in. They were nice old women—white-haired, sweet-faced, be-spectacled and all that. And to them Mrs. Arthur Miller was just like a Mrs. Frank Jones or a Mrs. Stanley Smith.

“I’m sure,” one of them said to Marilyn sweetly as she began to leave the post office. “I’m sure that were not the first to congratulate you, but . . .”

“Congratulate me?” Marilyn asked, puzzled.

“Oh now. Mrs. Miller,” the second little old lady said, shaking a finger.

“Oh now, what?” Marilyn asked.

“Mrs. Miller,” the first woman said, “we just wanted to congratulate you on your . . . your enceinte condition.”

Marilyn didn’t know much French. But she did know that enceinte meant pregnant.

“Oh.” she said, softly. Then she began to blush. “I . . . I . . .” she started to say.

“You ARE enceinte, arent you?” the second woman asked.

Marilyn smiled. “I . . . I think so,” she said. And then Marilyn said goodbye and left.

“Mmmmmmm,” said the first woman turning to her friend, “I know so.”

The news was all over town within a couple of hours.

It all lasted for about a week after that—the fun of everyone in town playing armchair godmother and godfather to a baby who was still seven months away but whom everyone was waiting for as if the baby was their own—because they had come to love the baby’s parents so much already.

And then, suddenly, at about eleven on the morning of Thursday, August 1st, the happiness came to a sudden end.

At first, Marilyn thought the pain was something momentary. But after a few minutes it began to grow worse instead of better. Suddenly, she clutched her abdomen and fell on her knees. “Arthur,” she called. Her voice was unnaturally weak. She tried to scream. “Arthur . . . ARTHUR!”

Arthur lifted Marilyn from the grass and gently, as gently as he could, carried her up to their bedroom.

“Please, God. . . .”

“The baby,” Marilyn moaned as he placed her on the bed and as she clutched her stomach again. She began to cry and the tears began to come uncontrollably. “I’m afraid for the baby, Arthur . . . I’m afraid for the baby.”

Marilyn was afraid, more afraid than she’d ever been in her whole life. “I don’t want to lose it, Arthur,” she whispered. She closed her eyes. “Please, God, I don’t want to lose our baby.”

Arthur spoke to the doctor a few minutes later. “Is it the baby?” he asked.

The doctor nodded. “I’ve just phoned for an ambulance,” he started to say.

“Ambulance?” Arthur asked, shocked.

“We’ve got to get her to New York right away,” the doctor said. “I’m not sure yet, but we may have to operate.”

This was all coming too quickly for Arthur, much too quickly. “Operate?” he asked. “Why?”

“In order to save your wife’s life,” the doctor explained simply.

The trip from Amagansett to New York took a little more than two hours. Two hospital attendants rushed out of the building to wheel the stretcher on which Marilyn lay, covered by two heavy white blankets, up to her room on the ninth floor.

The pain had subsided a little, and she had slept during part of the long ride. She really didn’t wake until she had been placed in bed. She opened her eyes slowly. She saw Arthur. She smiled a groggy smile. According to a nurse who was present at the time, “It was as though she was a woman in her own home and it was first thing in the morning and she’d overslept a little and she was smiling up at her husband, who’d got up earlier and had made his own coffee and was on his way to work.”

THE END

—BY N. POLSKY

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1957