Elizabeth Taylor’s Side Of The Story

There is a terrible hurt in Liz Taylor’s heart.

Do you care?

Your answer—if you’re at all typical of millions of movie fans today—is probably, “Her? Who cares about her after what she’s done?”

But here is something that may surprise you. The hurt Liz feels is not the result of all the attacks that have been leveled against her in connection with the Eddie FisherDebbie Reynolds divorce case . . . not the result of the way some things she said recently about Debbie and, too, about her own late husband, Mike Todd, were ‘twisted’ by a certain well-known reporter.

Liz’s hurt stems, rather, from her being attacked as a mother.

The attack appeared in a newspaper column not long ago.

The column item—and we reprint it with all its sarcasm intact—reads:

Bravo to Elizabeth Taylor, whose infant daughter, Liza Todd, was recently hospitalized. Did Liz, with all her money, take a room in the hospital so she could be with her ailing tot day and night? Not Liz. Did Liz, during the hospitalization, sit home and bite her nails with worry instead of stepping out with Eddie Fisher? Not Liz. Did Liz, after Liza was back home, place her child’s crib beside her own bed instead of packing her off to a guest cottage on the other side of the Taylor estate? Not Liz. Well, our Miss T. may not win that Oscar everybody’s been wondering about. But she looks like a cinch for one award, at least: Mother of the Year.

That’s the item.

We won’t bother reprinting the name of the man who wrote it.

But we are bothered by the fact that the man who wrote it is a liar, that (and we know this for a fact) he is an opportunist who was once befriended by Liz and who has repaid that friendship by kicking her when she was down, that he is a man who—by his lies—has betrayed his profession and a fellow-human being.

We ask you now to read the following story, Liz Taylor’s side of the story, and to decide for yourself.

We ask you to read it in a spirit of fairness, with your hearts and minds opened wide.

We ask you to judge—once more —a woman who has been so often and so viciously judged in the recent past.

And we hope, sincerely, that after you read it you will say to anyone who smirkingly mentions her name: “Liz Taylor? Yes, I care about her again. And let me tell you why. . . .”

Our story begins late that dark and rainy afternoon last November. Liz was in the nursery, alone with Liza. The baby had been flushed and crying for the past hour and Liz had just taken her temperature.

“Oh no,” she said, aloud, as she looked down at the thermometer.

She looked back into the crib for a moment and placed her hand over the baby’s forehead. The intense heat that met her fingers seemed to spread through her own body.

“Oh no, no,” she said again as she sped from the room, to a phone in the foyer.

She dialed a number. “‘This is Mrs. Todd,” she said. “May I speak to the doctor—quickly please?”

The doctor was on the line a moment later. “Liza,” Liz said, trying hard to control her voice. “It’s Liza. She’s sick. I just took her temperature. It’s a hundred-and-three!”

She closed her eyes as she listened to the doctor say something.

And as the doctor talked, she heard the doorbell ring.

“Yes,” she said, “yes, Doctor, now—I’ll do that right now.”

She hung up and stood frozen for a moment.

The doorbell rang again.

Liz snapped out of her gaze.

“Eddie?” she called out, rushing to the door.

“Milkman, lady,” she heard a voice call back.

She opened the door.

It was Eddie, smiling away. “Now about those three quarts you ordered for tomorrow—” he started to say.

But when he saw the terrified look in Liz’ eyes, he stopped.

“What’s the matter?” he asked, reaching for her hand, still standing in the open doorway.

Liz told him about the baby, about her call to the doctor, about how the doctor had said he wanted the baby brought to the hospital immediately.

“The hospital?” Eddie asked. “Why can’t he come here?”

“Because—” Liz said. A sudden gust of wind flew past the house at that moment and a quick splatter of rain slapped against her face. “—Because he says there may not be much time.”

Eddie nodded. “Let’s take her then,” he said, leading Liz inside. As they walked toward the nursery he continued talking. “It’s probably nothing to worry about,” he said. “All babies get high fevers once in a while. You know that.”

But Liz didn’t answer.

“We’ve got to wrap her up well,” she said, instead. “Lots of blankets. We’ve got to keep her warm, Eddie. She mustn’t get a draught in the car.”

“We’d better hurry!”

They were in the nursery by now. Liz had picked her baby up from the crib and she held her close to her now and began to kiss her little face.

“Liz,” Eddie said, “I think we’d better hurry.”

He had looked at Liza these last few moments, listened to the terrible way she cried, noticed the way her tiny eyes seemed to bulge from their sockets in unfathomable and helpless pain.

He could see now that the baby was sick, very sick.

And so. again, he said, “I think we’d better hurry.”

And so, a few minutes later, they left.

The doctor was already at the hospital when they arrived.

Immediately, he took the baby from Liz’ arms and ran his fingers across her chest.

Then he turned to a nurse.

“Set up an oxygen tent,” he said.

He began to walk away.

Liz rushed after him and grabbed his arm.

“Doctor,” she said, “what’s wrong with my baby?”

“I can’t be sure yet,” the man said, softly. “But I think it’s pneumonia, a deep concession of the chess,” he continued.

“And she’ll be all right? Liz asked.

The doctor hesitated.

“I don’t know,” he said, finally.

Liz hand dropped from his arm. “I’d like to stay here with her,” she said, her voice suddenly numb, defeated. “I’d like a room here—or a cot in her room.”

The doctor shook his head. “That’s not allowed in this hospital,” he said. “Anyway, the disease is probably contagious and—”

He shrugged.

Then he walked away.

And as he did, Liz turned back to Eddie, still at her side; and her voice still numb, she said, “They think my baby is going to die. Don’t they, Eddie? Don’t they?”

It was nearly three o’clock the following morning. Liz sat in the empty hospital corridor. Earlier in the evening, she had phoned five or six times to find out about the baby’s condition. But always the answer had been the same:

“No change, Mrs. Todd.”

“We’ll let you know when there is, Mrs. Todd.”

“Why don’t you get some sleep, Mrs. Todd?”

At two o’clock Liz made up her mind: she would go to the hospital. She wanted to see Liza. She had to see Liza. Liza was her daughter and she had a right to see her.

So she threw on a coat, got into her car and drove to the hospital.

The corridor had been quiet, the reception desk empty when she got there.

Then, a minute later, a young man—obviously an interne—had appeared.

“I’m Mrs. Todd—” Liz started to say.

“I know,” the man had said, smiling.

“My baby,” Liz said, “—can I see her? For just a few minutes. Please.”

The man had been sympathetic. “I’m afraid not,” he had said. “I know how you feel. But she’s still in an oxygen tent. And it is against orders.”

She just sat there

“Orders,” Liz had repeated, softly, after him. And then she’d looked over at a bench and asked, wearily, “May I stay here for a while, for just a little while?”

“Of course,” the young doctor had said, “you just sit and stay for as long as you like.”

And so Liz sat there now, alone, in the empty corridor.

And it was about ten minutes later when she saw the two nurses walking toward her. She noticed that they looked at her and then passed her, heading for a small office a few yards from where she sat.

She noticed, too, that one of them made an attempt to close the door behind her, but that the door did not close full way.

And then she heard their voices as they talked.

“Recognize her?” one of them asked.

“Yeah,” said the other.

“I feel sorry for the baby,” the first one said. “Fever’s up to a hundred-and-five now.”

“Boy,” the other said.

“And she just sits there,” the first one said sarcastically. “Just look at her!”

“So what’s she going to do?” asked the other.

“I don’t know,” the first one said. “But I’ll tell you one thing. Any other woman I’d feel sorry for, sitting and waiting like that. But this gal—I tell you—she’s getting just what she deserves.”

“Oh stop it,” said the first one.

“I tell you,” the other went on, “—even the Bible says it: the sins of the parent will be visited on the child . . . You know what I mean?”

Liz didn’t hear the answer to that question.

She didn’t hear anything more, except those words one of the nurses had just spoken, those awful words:

The sins of the parent will be visited on the child.

For a while, she tried to wipe the words from her brain, hard, like a cleaning woman on her knees pushing desperately at a smudge of relentless dirt.

But it was no good.

For the words kept coming back to her.

The sins of the parent—

—Will be visited on the child . . .

The sins—

—The child

The sins—

—The child.

Suddenly, Liz got up.

She began to walk.

She walked down the empty corridor, slowly, aimlessly, her heart beating heavy inside her.

When she passed a phone booth, at one point, she thought she would hide herself inside it and call Eddie and talk to him—just the way she used to talk to him those nights after Mike had died, when she had needed someone to talk to and when he’d seemed to be the only one she’d wanted to talk to.

Alone . . . but for God

But, now, at this moment, though she had no one, though she wanted someone, she decided no. It was late, she knew, and Eddie had sat up most of the night with her before going home to the little hilltop bachelor place he’d moved into after his split with Debbie, and he had an important rehearsal in the morning—and no, no, she couldn’t wake him up now, no matter how much she needed him.

And so she continued walking, past the phone booth, past the water fountain there against the wall, past the doors marked Ear Clinic and No Admittance and Positively No Admittance.

And then, finally, she came to the door marked Chapel.

And she paused.

For a minute, she simply stood there, looking at the door.

But then she found herself walking towards it and twisting the knob and entering the room.

The room was dark. Liz lifted her hand and felt the wall for lightswitch and, finding it, she clicked it. Slowly, it seemed, the tiny room came bathed in soft, warm light.

She closed the door behind her.

And, alone now, completely alone, she began to pray.

“God,” she whispered, walking to the font of the room, then kneeling, staring at he plain gold crucifix tacked to the wall across from her, the nurse’s words spinning through her brain. “God . . . They say I have sinned. They say I am bad—that I must pay for being bad.

But God—You are the One who knows, really knows. You are the One who will find me guilty or not when the time comes.

“So God—please—for now—if there is any punishment to be dealt—don’t punish my baby; not Liza, my baby, my little girl.”

Liz shook her head and the tears began to rush into her eyes.

“She’s so little, God . . . She’s never hurt anyone . . .. She’s just a baby.”

Again she shook her head.

“Oh, I’ve suffered, God,” she went on, desperately. “—Last March . . . Mike . . . That night in the plane . . . And then he was gone . . . And now—not Liza. Not our daughter.”

The tears streamed from her eyes.

She brought her hands together.

And, suddenly, her voice shattering the heavy silence of the holy room, she screamed out:

“Please—I’ve lost the one person who meant everything to me. Please—don’t take our baby away from me, too. . . .”

Two terrible weeks

The next two weeks were the most terrible Liz has ever spent. The baby remained in the hospital, in critical condition, strangely allergic to any of the antibiotics she was being given to help her fever—that fever enormously and consistently high. And Liz, meanwhile, remained closeted in her home, always on the phone with the baby’s doctor, visited by a few close friends—including, of course, Eddie. Once in a while, someone would suggest to Liz that she and Eddie go out with them, to a movie, or a restaurant, or a nightclub—anything, just so she would get her mind away from her worry. But, always, Liz would say no. “I’ve got to wait,” would be her answer. “I may leave the house. And the phone may ring. And—”

Then she would stop and, her body tensing, she would repeat:

“I’ve got to wait. I’ve got to, got to.”

The phone did ring, finally, very early that morning exactly two-and-a-half weeks after Liza had been taken to the hospital. Liz, half asleep, got up from her bed and answered it.

She sensed, right off, that it was the hospital calling. At first she was afraid. But she knew she must be brave.

“Hello?” she asked, nervously, her fingers clutching to the receiver.

Then she heard the doctor’s voice.

“Mrs. Todd?”

Liz could barely answer him.

“Yes—this is Mrs. Todd.”

“I have good news,” she heard him say.

“You—?” Liz started to say.

“Good news,” the doctor said. “Just a little while ago we found a serum the baby can take. Her fever has started to drop . . . It was touch-and-go there for a while—I don’t mind telling you that. But your little girl is going to be all right now, Mrs. Todd.”

Liz felt her knees go weak, her head begin to spin.

She fell back into a chair.

“All right, you say?” she asked, still not believing it.

“All right,” the doctor assured her.

Liz closed her eyes. “Oh thank you, oh thank you . . . thank you, thank you, thank you,” she whispered.

Then, after talking a little while longer and hanging up, she continued sitting there, and she thought.

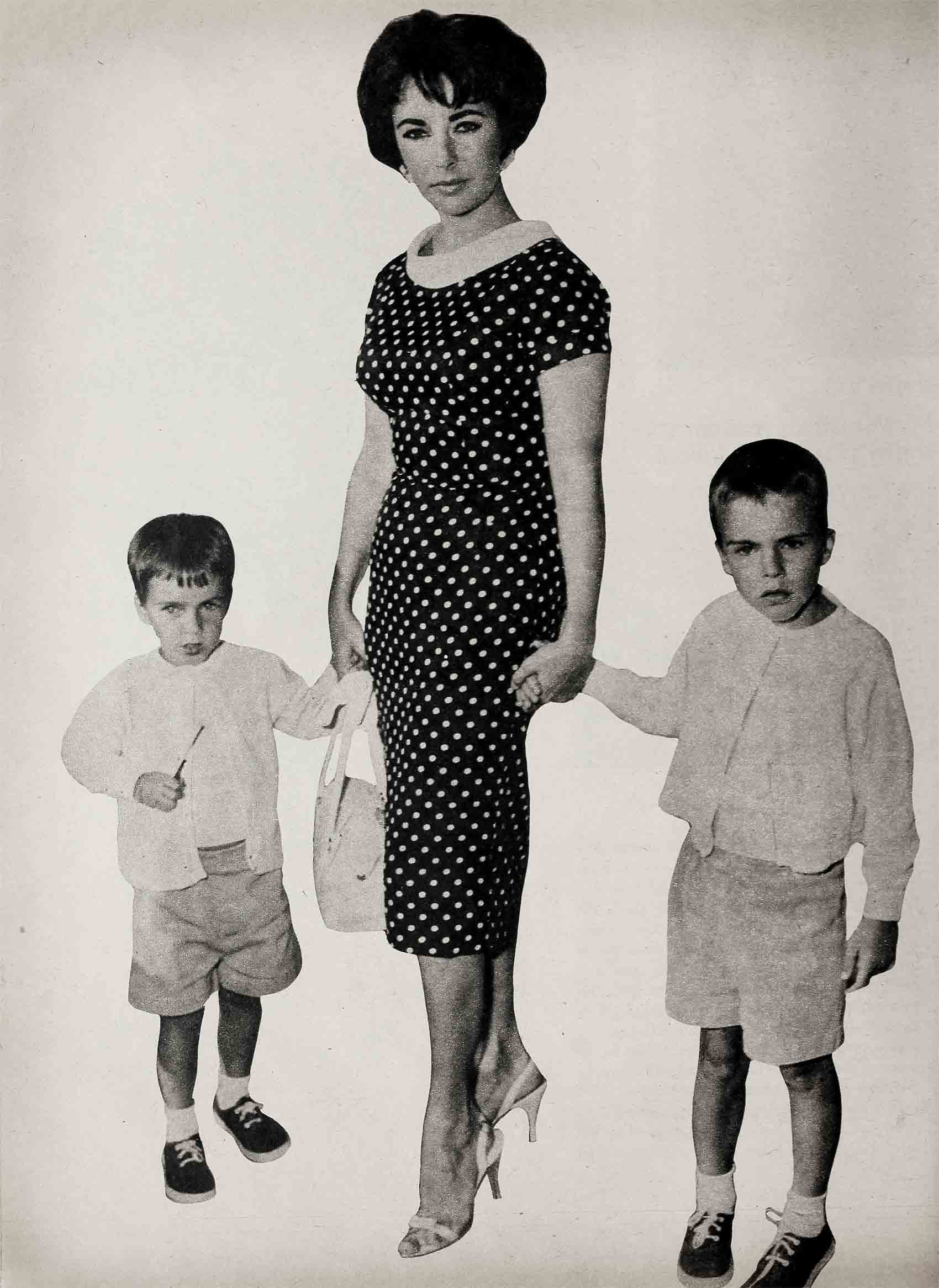

In a few minutes, she thought, she would call Eddie—who’d been suffering through these past weeks with her—and tell him the wonderful news. And then, right after that, she would go down the hall to the room where her sons, Michael and Chris, lay sleeping, and wake them and tell them. To young Chris, especially, who only the other day had said to her: “Mommy, my friend next door told me that Liza is never, ever gonna come home again. Is that true, Mommy?”—to him, now, she could say: “Liza’s getting better, darling, and she will be back with us soon!”

Liz was never more radiant than the day she went to the hospital to bring her baby home.

Before going upstairs to get the baby, she stepped into the doctor’s office for a moment. There, she listened as the doctor discussed medicines Liz would need, details of the care she would have to receive, and the fact that because the baby was not completely well and that what remained of her sickness could still be labeled contagious she would have to be isolated from Liz and the boys.

“You mean I can’t keep her with me?”

The doctor shook his head. “For a month, at least, I want her kept with a nurse in separate quarters,” he said. “Do you have a guest cottage on your grounds?”

“No,” Liz said.

“Then I suggest a room at the far end of the house, away from the boys.”

Liz nodded. Almost meekly, she asked, “But can I get to see her at all?”

“I think it would be all right, for a little while every day,” the doctor said.

He smiled.

“Want to come get your daughter now?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said, getting up, too, “oh yes.”

“Then what are we waiting for?” the doctor asked, taking her by the hand now and leading her out of the office. . . .

What happened next can best be described by a nurse who had taken care of little Liza most of these past three weeks and who accompanied Liz and the doctor to the baby’s room now.

“Before this particular morning,” the nurse has said, “Miss Taylor had only been allowed to see her daughter through a glass partition. But now that she was able to go into the room—well, I thought she was going to fly through the door before we even had a chance to open it. And it was really something to see—how she rushed right over to the crib where the baby lay and scooped her up in her arms, how she called out ‘Liza!’ over and over again, laughing and hugging the baby and covering her with kisses . . . how the baby began to laugh, too, and say ‘Ma-ma, Ma-ma, Ma-ma,’ how the two of them, together like that—well, it was really something to see.

Tears of thanks

“For the next few minutes, after they greeted each other, I helped Miss Taylor dress the baby.

“Then, when it was time for them to go, Miss Taylor walked over to where the doctor was standing and she kissed him.

“I’ll never forget what you’ve done for us, she said.

“She turned to me next.

“ ‘I’ll never forget,’ she said, walking over and kissing me, too.

“ ‘It’s been a pleasure, believe me, to see the baby make such wonderful improvement this past week,’ I said. ‘And it’s been a pleasure, too, just being with her,’ I said, ‘because she’s such a good baby and such a beautiful baby.’

“ ‘Thank you,’ Miss Taylor said.

“Then she looked down at her daughter, nestled in her arms.

“ ‘Her daddy would be very proud of her right now, wouldn’t he?’ she said.

Then she stopped.

“And I noticed that she had begun to cry a little as she said that.

“So, for the next minute or two, we just stood there, looking at the baby.

“And then, her head still bowed, she whispered good-bye and left for home—just her and the baby she was hugging so hard. . . .”

THE END

Liz’ next picture will be TWO FOR THE SEESAW, for United Artists.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1959