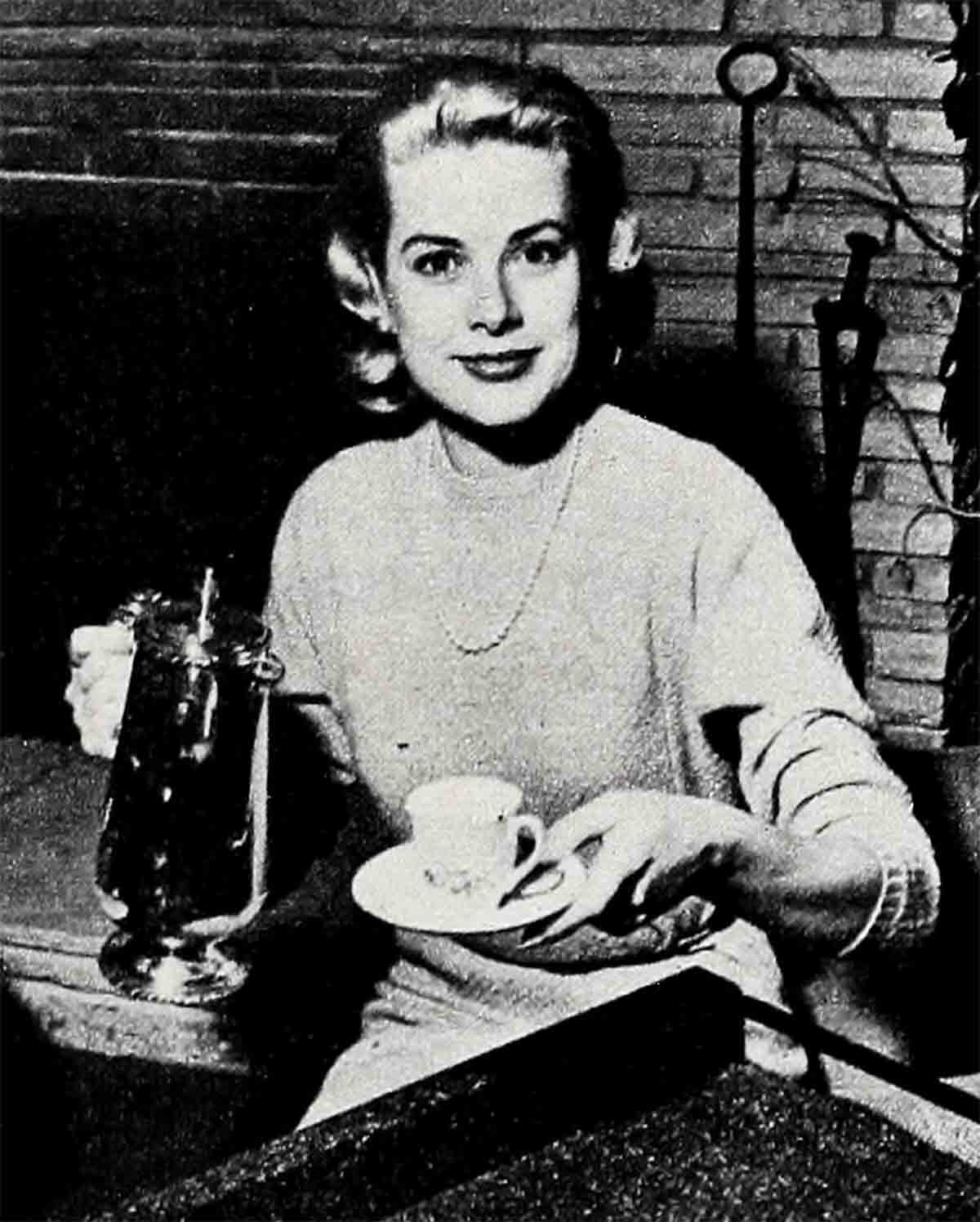

The Lady Is A Go-Getter—Grace Kelly

“I’ve never been depressed by my work. I love it. If Forget all the blarney about it became a chore, I’d give it up,” says Grace Kelly. “I’ve had a couple of parts I didn’t like. I was bored and miserable. I couldn’t work up any sympathy for the She was, in her own words, characters. If I had to do much of that I’d stop cold. The day I find acting is no longer fun and exciting, I’ll quit.”

The lady says what she thinks. She is shy but never punishment is what she got! scared. If she has something to say, she says it. If she has nothing to say, she is a phenomenon—she says nothing. Physically speaking, she is well modulated with a figure that neither screams with exaggeration nor retreats in a whisper. She is lithe and tall with a remarkable face that produces the fragile smile of a Mona Lisa or the grin of a child looking up delightedly from a double banana split.

This is the girl a lot of people are talking about. She’s got them confused, for no matter what they want her to be—another Ingrid Bergman, a well-scrubbed kid, a Cinderella type, a snob, a shy filly—no matter what they want, she insists upon being Grace Kelly.

“Everything’s happened—all the publicity—in the past year,” she says. “So I get the sweepstakes’ winner treatment. Frank Sinatra was talking about this and he said, ‘I remember they called me an overnight sensation. It made me sore. It wasn’t overnight. It was ten years of hard work.’ ”

And Grace Kelly? Well, she wasn’t discovered pedaling a Good Humor wagon down Sunset or posing for cheesecake as Miss Light Bulb atop the Empire State Building. The fact is that Grace, at twenty-six, has been in amateur, semi-pro and legit theatre for fifteen years. At eleven she auditioned for, and was accepted by, a little theatre group, the Old Academy Players in Philadelphia, and until she moved on to New York, she worked with that group as well as church and school dramatic clubs. Prior to the age of eleven, when she was just a child, she played the neighborhood cellar-circuit in a repertory of Mother Goose. She was always imaginative. Dolls weren’t just dolls; they were puppets.

“I was a long time growing out of dolls. Even when I was thirteen and it wasn’t proper to play with them, my younger sister Liz could easily coax me back to them just by promising not to tell anyone else, especially the boys. I always liked make-believe games. But what helped me succeed, I think, is that different opportunities came along at a lucky time. They didn’t come before I was ready, if you know what I mean. There’s all this talk about making your opportunity but what’s the good of breaking down a door before you’re prepared?”

The story of Grace Kelly is that of an earnest, intelligent girl who has been making ready for a long time. It is generally assumed that because her father is wealthy, Grace never had to peel her own orange. Well, it’s true. Her father is rich and their orange juice came in small cans, frozen and concentrated. He paid her tuition when she entered the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York, but five months after she left home, Grace was fully supporting herself, room, board, tuition and nylons—and she was just turning nineteen.

To become self-supporting, Grace stayed awake and worked many hours every day. From nine to one she was in school. Until early evening she modeled or she went through the grueling task of marching from agency to agency being interviewed for future jobs. In the evenings, she studied and prepared for the next day’s classes.

“I was a glutton for punishment,” Grace says.

Her work at the academy didn’t suffer. Her acting in a play at the academy was so exceptional that a talent scout recommended her for a studio contract. Came summer and she had earned herself a rest in the family’s summer home. The house is on a New Jersey beach where ocean surf tickles your toes and cool sea breezes make sleep possible. Grace didn’t even get down there for a long week end. In the oven of Manhattan she modeled furs and woolens for fall buyers. While most of the gals booked out for long week ends, Grace worked six days a week.

Grace modeled through her second and last year at the academy. Even when she began to pick up dramatic parts with regularity she continued to pose pretty. She won a part in a Broadway play that had a three-month run and still worked through the day as a model. It was only when she began to get television parts by the score that she had to give up the hatbox.

“I learned things as a model,” she says. “I learned something about what to do in front of a camera. I learned what kind of clothes were best for me and how to wear them. I learned to stay on my feet until my head hurt.” She recalls, “You know, I think the hardest part of modeling was staying well-groomed all day. You might have your first appointment at nine-thirty in the morning and another job in the later morning and maybe a couple more in the afternoon. When you showed up for the last job at four you had to look as if this were the first of the day.”

She progressed from $7.50 to $25-an-hour jobs. She wasn’t merely a good-looking girl, but she had sense and poise and endurance. And the work was demanding. There was the suntan lotion poster she posed for. She was in a swim suit and the photographer had her stretch out backside up. Then he had her raise her head from the waist so that she slanted up at approximately a twenty-degree angle. “If anyone thinks twenty-five dollars per hour is overcompensation for such work, let her try to hold that pose long enough to get several full-color shots,” comments Grace wryly.

Although the Kelly face and figure graced the cover of many magazines—repeating three or four times on several—she learned, too, about the inconsistency of human judgment. One photographer complained about her leggy look and another looked and liked. One would pose her and then order, “Close your mouth. Don’t smile. Don’t ever smile.” And the ‘next day, another photographer, “Not so glum, girl. Show your teeth.”

It was something like that when she auditioned for producers and directors. Grace at nineteen had reached her full growth of five feet, six and one-half inches, all of it fair and beautiful, with a couple of bright blue eyes and corn-blond hair. But in the theatre they gave her a hard time. She was told that she was too young for a character part. She was too pretty to be anything but an ingenue. She was young enough to be an ingenue but too tall for that. And then she found a director who wasn’t bothered by her height and was impressed by her reading. He turned her down saying, “You look too intelligent.” Finally, she won a part in a Broadway show, “The Father,” and much to her surprise she wasn’t cast in the title role. Raymond Massey had that part and Grace was appropriately his daughter. The play ran three months and led to her first screen role in “Fourteen Hours” in 1951, another play, a short-lived one; and then little Grace Kelly, just out of the city where they cracked the Liberty Bell, had as leading men in rapid succession, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Ray Milland, James Stewart, William Holden, Bing Crosby, Stewart Granger and Cary Grant. All in less than a couple of years and all so recently that some of the pictures aren’t yet released. It sounds easy. It wasn’t. Even Grace couldn’t keep count of the dozens upon dozens of auditions she didn’t pass before the breaks came her way.

“You go to the audition. You wait your turn to read. You’ve been turned down so many times before that you say, ‘Oh, please, God, let this be it.’ This one is the important one. And you wouldn’t get it and you had to forget it and try another. You had to forget it right away. You just tried another. Every one was important. A young actress has to have more bounce to the ounce than Pepsi-Cola.”

Grace, in those days, was proving she had been properly prepared for certain problems of an actress. She had stamina and determination and she wasn’t discouraged by criticism and failure. She demonstrated a capacity for work and a willingness to learn. Grace gathered these traits from the same woman from whom she derived much of her charm and beauty, her mother.

Mrs. Kelly believed in responsibilities for children—Grace had chores. Mrs. Kelly was strict—Grace learned to be orderly and organize her time. Mrs. Kelly said no when it was appropriate and did not hesitate to correct—so Grace grew to be a young woman who was neither rattled by criticism nor broken down by refusals. These were some of the things that were important to Grace along with the make-believe fun and parlor games that her parents encouraged and participated in. But when Grace went to the academy, at the age of eighteen, she had already acquired a trait most important to an artist, self-discipline.

“Discipline is getting up at six A.M. in Hollywood when you’d rather be in New York waking at eleven. Discipline, too, is learning something new and strange or refusing a second piece of cinnamon toast. Discipline is not putting things off until tomorrow.” ‘Grace Kelly feels strongly about this last point. “If today is for buying spring clothes, you buy them. If now is the time to take singing lessons, you take them now, not next year. Next year you can take singing lessons, too, but they are next year’s lessons. There’s a time for everything.”

But sometimes, even for Grace, there’s not time enough. When Grace came to Hollywood for “Dial M for Murder,” she hardly had time for a second breath before she was at work on “Rear Window,” “The Country Girl,” “Green Fire,” “The Bridges at Toko-Ri,” and “To Catch a Thief.”

“When you’re working on a film, you put everything into it. For months at a time. You lose yourself in the work. Then, when it’s over, you try to catch up with your other self, the part that’s not the actress. You try to catch up with the part that’s a private citizen, a daughter and sister, a friend.”

This past fall, after six pictures, Grace had her first real vacation. She spent it in New York and Philadelphia with her family and friends. She played tennis several times a week. She got a lot of sleep—ten hours a night when possible. She took singing lessons.

She already speaks French and Spanish. But she is still studying them. She recalls with little pleasure the feeling when you’re not prepared.

“There are all kinds of nervousness. When I was eleven and got up on a stage, it was all gravy. For a child it was wonderful having all those people watching. It wasn’t until I played Peter Pan in our graduation play. That was in Philadelphia and I was about sixteen. I think that was the first time the nerves came along—and that was more nervous excitement and it lasted just until the curtain went up. It’s not that you’re afraid, it’s just that you can’t sit still waiting for things to start.” And then there was the one time it was a different kind of nerves. “I was to do a song and dance on Ed Sullivan’s ‘Toast of the Town.’ Well, a song and dance wasn’t my specialty. I was scared. I didn’t want to go on. That was the worst time I’ve ever had.” She mulls a bit and goes on, “You do have this nervous excitement—the good kind—in making a movie, too. The first few days on a set you have it and then, too, when you’re doing an important scene. When we were filming ‘The Country Girl’ we did two important scenes one right after another and that gets you up for a long time. The continuous intensity for days at a time is something. You feel it.”

It is obvious that she takes her work seriously, but she has never sacrificed her dignity and personal integrity.

“You can’t be afraid of what you believe in,” she says. “You must be true to yourself.”

And while she is in earnest and has been in earnest about her career, having prepared for today, preparing for tomorrow, Grace acknowledges the element of luck.

“Look, I remember I had two scripts to choose from. One was ‘Rear Window.’ I can’t tell the name of the other script. It wouldn’t be fair to the girl who took it. But I had to choose between the scripts and I liked them both. I wanted to do both. I was in my agent’s office and he said, ‘Decide!’ I couldn’t. I told him, ‘I want both of them.’ He said, ‘You can’t. You’ve got to decide on one. You’ve got ten minutes.’” Grace smiles, catches a second breath and goes on, “Well, if I hadn’t chosen ‘Rear Window’ there wouldn’t have been ‘Bridges’ and ‘Country Girl’ and the others. Who knows where I’d be? But that’s not the point anyway. Suppose I’d had to make that decision a few years earlier. I wouldn’t have been lucky either way. I wasn’t ready.”

So if you want to be a star, a self-made star—first learn the Boy Scout motto and then, like Grace Kelly, be smart and independent, hardworking, ambitious and honest, lovely and considerate. And then there’s the matter of strength. If Grace Kelly were a man—an impossible challenge to the imagination—but if she were a man, with her fortitude, her courage her decisiveness, and the right trainer—she could be a champ, a boxing champ of the world—or just about anything else she chose.

THE END

—BY MARTIN COHEN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1955

No Comments