Non-Stop Terry Moore

Yours is a famous face and figure. Your sunny smile and vivacious personality are pinned up in the huts—and in the hearts—of GI’s in every far-flung outpost of Uncle Sam’s.

But in your life there have been many shadows behind that smile, and your story is as poignant as your own childhood favorite—“The Princess Who Couldn’t Cry.”

Yours has always been a divided dream and destiny as divided as the conflicting desires and hopes and hurts of a famous and ambitious actress and an everyday All-American girl. Your triumphs have been tempered—and clouded—by your younger tears.

Here is that untold story. Read—and recall with us—as we unfold pages as revealing as those deep in the heart of any young girl’s diary. Pages from your story, Terry Moore—for this is your life. . . .

It begins January 7, 1929, at the Lutheran Methodist Hospital in Los Angeles when a bouncing baby girl is born to Luella and Lamar Koford, an investigator for the Retail Credit Company. But let’s let your “producer” supply the details.

“Terry was a bouncing baby, all right, Ralph. Take her mother’s word for that. She was the fattest little thing I’ve ever seen. It was the fad then to name girl babies Betty or Shirley—but we chose Helen—because I insisted on a more substantial-sounding name. She had the prettiest big blue eyes—but she had no hair at all until she was three years old. Not even enough to put a ribbon on. In spite of the fluffy bonnets I made her and the big ribbon bows I used to put on her baby carriage—people would still say, ‘He’s a nice healthy fellow,’ or ‘My, what a big husky boy.’ I could have killed them!”

But the following year you need every ounce of that strength. You have lobar pneumonia, and in the hospital the tense hours tick by . . . the hours that will decide whether you live or die. Outside a glass window, your parents stand watch and pray.

“Yes, Ralph. we nearly lost our girl that year. The doctor didn’t give us .much hope. They did all that medicine could do. But her father and I will always feel that prayer—not only our own, but the prayers of all our friends and the members of our church—helped pull Helen through.”

Out of near-tragedy often comes some measure of good. Because of a bronchitis condition which results, your parents move to a higher altitude in Eagle Rock where you are to meet the neighbor and landlady who will some day “stake” you in the first step of your motion-picture career.

At three you’re a chubby Calamity Jane, listening to “The Lone Ranger,” and riding the prairies of your backyard on your fiery Shetland steed.

At seven you’re the darling of the pigtails and pinafore set. And determined to some day be a motion-picture star. From infancy, your mother has recited readings, instead of singing you to sleep, and soon you commit them to memory. You try them out on an uncomplaining audience—your adoring younger brother, Wally, your dolls, two ducks named Donald and Clara Cluck and a dog of somewhat doubtful parentage, Prancer, a refuge from the Pasadena dog pound. When the other girls play nurse, you’re always a motion-picture star. Jane Withers is your favorite. You play movie-star hopscotch—putting the initials of stars in the. squares. When you visit Brigham City, Utah, in the summer, your cousin goes you one better—for one cent he sells your autograph.

January, 1939—you go with your parents to see Shirley Temple in the Rose Parade. She’s wearing the white ermine costume and muff from her last picture, “The Little Princess,” and to you, Terry Moore, she’s the most glamorous creature and the most talented who ever lived.

Yours is the typical life of almost any ten-year-old. You proudly join the Campfire Girls, and with your customary drive, whatever the chore, you win more wooden beads than any of them. One such achievement is cooking, and your family gets plenty sick of “Apple Betty” before you “bead” that one line. You attend Mormon Church and Sunday school faithfully. You’re still torn between Dick Tracy and The Lone Ranger. But now, significantly, you begin to hang on every word of radio serials like “Our Gal Sunday” and “Helen Trent.”

In 1939, too, you realize beauty must pay a price—when the dentist insists on braces and corrects a couple of twisted teeth and changes a bite plate to your own bite. But it has its compensations when you fall, at this tender age, for the boy who shares his scooter and skates with you. To your diary you confide, “I’ve got a boyfriend. His name is Robert MacDougal. He likes me, too, cause he said so. Today he came over looking for his skate wheel.” As good an excuse as any—at ten.

January 26, 1940—you pass into the sixth grade—and into what is to be perhaps the most important year in your life. Your lucky eleventh year. But it has its bad moments too. For this year your classmates start calling you “skinny”—and you really suffer. How much—only one Terry Moore can tell.

“The limit, Ralph, the absolute limit. For a girl who started out so fat—I’d really thinned down. I was the last girl to develop in our crowd. When all the other girls were shyly concerned about concealing what they had, I was still wearing loose blouses under loose sweaters, in the hope of concealing what I didn’t have. I was so self-conscious about being skinny, and the boys were always kidding me about it and pointing to my legs. I was thoroughly crushed about the whole thing. Funny—how acutely you remember—but I’ll never forget the day my whole world fell. I can still see the classroom—and the desks we all had. My girl friend, Barbara Metzler, sat across the aisle from me, and one day when Robert MacDougal came down the aisle, she put her leg across to my desk, blocking him. “Put those million-dollar legs down,” he said admiringly. Well, I just about died. It seems funny now. But I remember vowing right then that some day, some way, ‘He’s going to say the same thing to me.’ I felt so humiliated. And since I was planning on being a movie star anyway, I also resolved to have the most photographed legs in the world. I sat there dying and really dreaming it up. ‘Million-dollar legs, huh? I’ll show him.’ Funny how those things stick with you. ‘That’s why I’ve always been so willing to pose for cheesecake—until now.”

But yours is a victory in 1940, too, Terry Moore, for this is the year your star is born. One day your neighbor and landlady, Mrs. Annie Lorraine Jensen, encloses a ten-dollar bill with your pinafored picture and sends them to the Welles Casting Directory. Why did you take that gamble, Mrs. Jensen?

“I’d had my eye on Helen since she was two years old, Ralph. Whenever Mrs. Koford came over to pay the house rent, she always brought her little girl with her. Sitting on a stool, her feet not even touching the floor, Helen would raise those big blue eyes and recite. She had a lot of poise too.”

February 10, 1940—the day you first stepped inside that world of make-believe you’ve long dreamed is your own—will be engraved forever in your memory. The studio casting agent, looking for a child to portray Brenda Joyce as a child, saw your picture in the casting directory and called your home in Glendale. You weren’t home for that first magic ring, but your father, Lamar Koford, filled in.

“You might say they filled me in, Mr. Edwards. ‘Do you have a little girl, blond, with big teeth?’ they said. I was startled for a minute, never having exactly thought of Helen that way. Finally I said, ‘Why, yes, we do.’ And when her mother and Helen got home, they rushed right to the dentist to have the braces taken off her teeth. When they got to the studio, the casting fellow looked at her and said, ‘Would you object to her wearing braces for this part?’ And they rushed back and had Helen’s own put back on.” Your mother says, ‘Helen seemed to sense she belonged right there.’ When we left the studio, she said, ‘I don’t know why, but I wasn’t a bit afraid. I read the lines and I could answer everything they asked me, and I wasn’t afraid at all.’ ”

You live on wings—as the magic land of make-believe you’ve envisioned unfolds before your excited blue eyes. It’s your fairy tale come true, but you’re the little Princess and it’s all happening to you. That first night a happy little girl scribbles in her diary, “I got chosen. I’m one of six for a screen test tomorrow. Oh boy!”

Then the long wait begins.

You’re eleven years old now, Terry Moore, and you play with paper dolls and listen for that phone to ring. Only you and your diary know how hard you listen.

Finally, on March 9, you report to the studio at 8 a.m. A big limousine takes you out on location but it’s too windy and you don’t work. Four days later you work before the cameras for the first time. Your director is Henry King, who will direct a star named Terry Moore in “King of the Khyber Rifles” thirteen years from now. You ride a horse bareback in the scene and the studio pays you $125 for the week and you leave the studio gate that night starry-eyed and dreaming of wonderful things to come.

You’re Walter Brennan’s granddaughter in the picture. You’ve gone to Studio School with Peggy Ann Garner and Linda Darnell, still not eighteen. You’re in the movies now.

It’s so thrilling you can’t wait to get back to school and tell the other kids all about your new world of make-believe and share all your exciting experiences with them. But you are to find sadly, Terry Moore, that few want to listen. There’s a world separating you now—a world of make-believe they cannot enter. And there’s a wall, a magic studio wall that is strengthened by envy and a natural jealousy through the years. This heartbreaking wall you can never break down.

You live in a half-world now, Terry Moore, a divided world—of a child and an actress. A world of highs and lows, triumphs and tears. How divided your world is your own diary tells.

“Mother bought me a new yo-yo. Big geography test tomorrow. We don’t know yet about the interview.”

You’re thrilled when you audition at NBC for “One Man’s Family” and when you go on a picnic with the Campfire Girls. You’re heartbroken when you fail to get an “A” in typing and when you miss a studio call. You’re ecstatic when Fox calls you for retakes—and full of despair when you can’t find “the wire that goes on my teeth.” And your eleven-year-old heart is torn between love for Cary Grant, whose daughter you portray in “The Howards of and a half-shepherd dog named Tillie a neighbor gives you.

The phone rings and you’re excited about an interview for “Cinderella,” but you hear words that will become very familiar. “You’re not the type.” The call is for one of the wicked stepsisters and you’re “too pretty” for the part. This happens again and again. It seems this is the year for little freckle-faced girls who stick out their tongues—the female Butch Jenkins. You watch the mirror wistfully for freckles that won’t appear. But professionally, 1940 is still a busy year. You’re chosen on your first call for photographer’s model, and Natalie Graske, then Mrs. Tom Kelley and now a client of the agency, remembers that afternoon well.

“We’d interviewed some twenty children for a color shot of a little girl trying to bake cookies for the magazine The Country Gentleman. Tom took Terry immediately. She didn’t look like a professional model. She looked like any typical little American girl with flour on her face trying to bake cookies. Then, too, the other kids didn’t have Terry’s intelligence. After that first sitting, I remember Tom said, ‘She’s got it. That kid will get someplace some day.’ I was impressed. Tom doesn’t say that about too many models.”

You will get there all right, Terry Moore. Your fresh wholesome All-American face will show upon the covers of every national magazine. But every step up in this exciting new world will alienate you more from the other world and the classmates who mean so much to you.

At school they call you “Spitfire” because of that drive and ambition, that quick mind of yours going a mile a minute with always a million ideas. They nickname you “Two Tongue” for that tongue of yours that’s always going a mile a minute too. They resent a little the spotlight that, wherever you are, is always to be inescapably yours. And they shrug off with seeming disbelief any mention of your being in the movies.

Anxiously you wait for your first movie to come out. Then, you think, they will be convinced and they’ll be excited too. When you see in the paper that “Maryland” is opening, you run to show your mother. She cries and tells you what Walter Brennan had told her months ago —that you have been cut completely out of the picture. It isn’t your movie any more. And you can’t make-believe this hurt away.

At school the next day you face the cold eyes of classmates who went to see the movie the night before. They accuse you of lying. You weren’t in the picture at all. Or else you must be pretty bad for them to cut you out. You’re no actress if they cut you out. The Little Princess can’t cry. And in front of them you don’t, but that night at home in your bed your diary knows.

“December 4, 1940. The kids weren’t a bit nice to me.”

It’s 1941, and you’re in Wilson Junior High now, Terry Moore, and this is your life.

Studying, swimming, horseback riding, miniature golf and netting one dollar a week for helping your mother with the housework. And, of course, the boys.

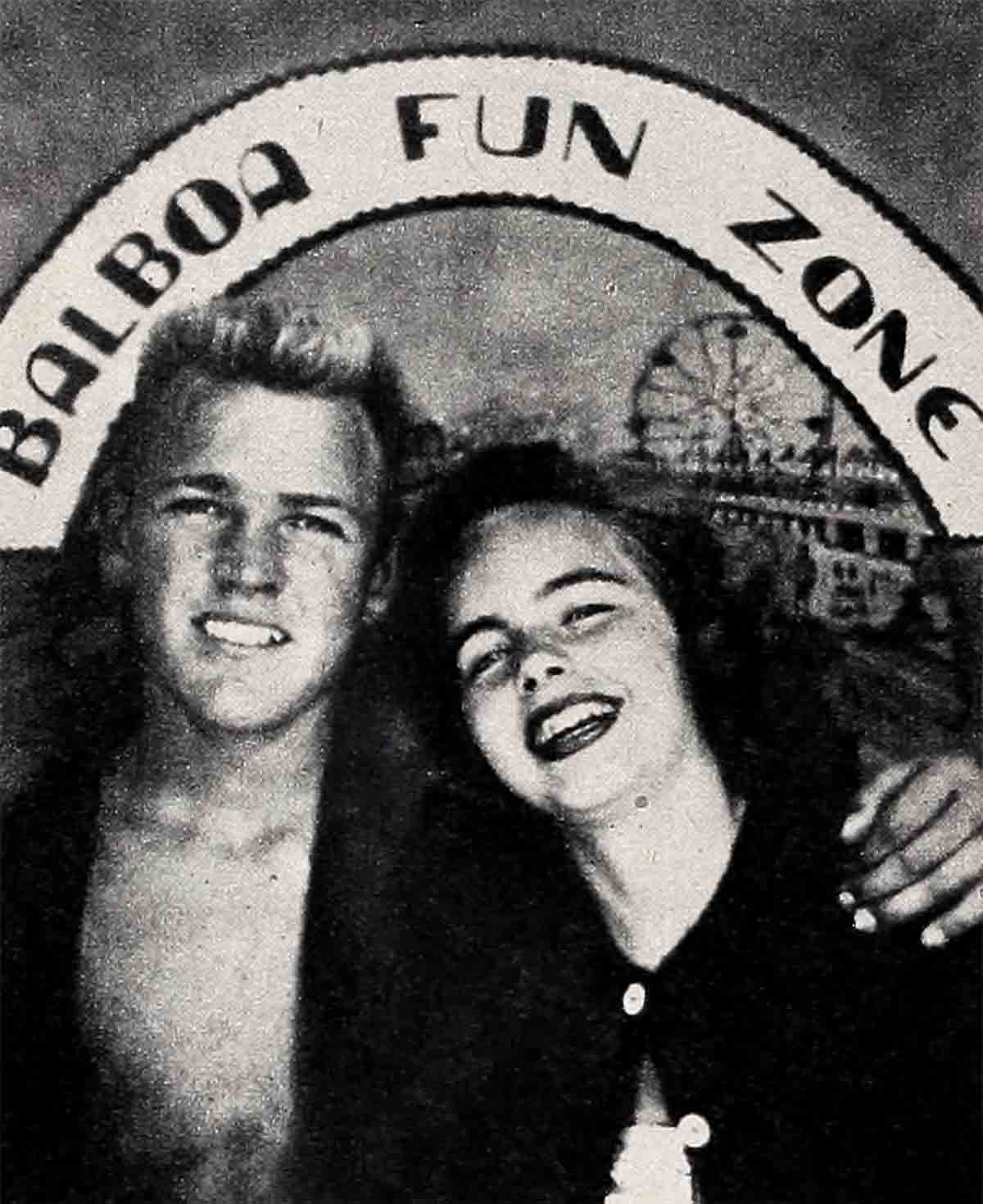

Those who previously called you “Skinny” are giving you the eye now. Puppy love is rampant. And you’re “number one” again with your old friend, “Mac.” You’re really living when he invites you to meet him at the Alex Theatre and promises, in addition, to buy you a candy bar. The prevailing custom heretofore has been for girls to attend together, leave one empty seat beside each of them and be joined by the gentlemen when the lights come on.

These are important times for the young in heart. And Robert MacDougal who was one of your gang remembers it well. He’s now head of the MacDougal Door and Frame Manufacturing Company. Let him get a word in here.

“That was always the trouble, Ralph. I’ve known Helen Koford since the third grade. And I haven’t gotten in a word yet. Her tongue was always going a mile a minute, even with her bite plate in when she was having her teeth straightened. I’ll never forget one Saturday when I invited her to have lunch at our home. I wasn’t old enough to have a car or drive. So Helen took the bus over. During these days her dentist was changing her bite, and in the course of luncheon, she said suddenly, ‘Bob, you’ll just have to excuse me.’ And, turning her head, she swiftly removed the plate. She forgot and left it on the window sill, and late that night when we found it, I had my mother and dad drive me over to Helen’s house so I could return her plate.”

He’ll never know either, will he, Terry, how embarrassed you were when you answered the door and found your. plate carefully packed in a box of cotton?

And what’s this entry in your diary?

“Bill Chambers and I quit going steady tonight on the telephone.”

“This one really hurt, Ralph. Bill was my first steady. He never had a dime to spend on a date. Every penny he had he put in a car he was stripping down into a hot rod. Once in a while he’d borrow a relative’s car. And we’d ride down in the evening and watch the trains come in. When he finished his work on that car, we broke up.”

Yes, these are the tender years. For the first time you’re torn with the problem of love versus career. Your heart’s heavy when you get a crush on a boy named “Hughey,” a stable boy at a resort where you’re vacationing. You have to leave him to test for a part with Ingrid Bergman in “Gaslight,” but the show must go on.

And the show does. At 20th Century-Fox you play Victor Mature’s sister in “My Gal Sal.” Your face covers many magazines, and you get the part of Little White Cloud, Little Beaver’s romantic interest on the “Red Ryder” radio show. You and Tommy Cook are so small the studio gives you stools to stand on to reach the mike. You test for “Jane Eyre” but Elizabeth Taylor gets the role. You test for “Remember the Day” and Ann Todd gets this one. The real heartbreaker, however, is when you’re promised a big part in “True to Life” at Paramount with Mary Martin and Dick Powell. This seemed, at first, to be the best break yet, Terry Moore. You’re to get fifth billing in the picture and $250 a week for three months’ work. Also you get to wear an evening gown once worn by Veronica Lake. You check your books out at school to study on the lot. Then the night before you’re to report on the set the phone rings with the word that the producers have decided the part should be a and they’re using a “homelier girl.”

This is the worst blow yet in your make-believe world. To your diary you lament, “They wanted a real homely girl with freckles. I think that’s just what I am.” Then there’s a later postscript that same night, “I really don’t even think of it now.” But you both know you’re just whistling in the dark.

The toughest part is walking into school the next morning with bowed head, carrying all your books back again. An actress? Not much. Not if they replace you in the part. By now, you seldom speak of movie work. As an old school friend, Bob Wast, today president of your fan club, can well recall.

“She did tell me when she got a part in ‘The Clock’ with Judy Garland and Bob Walker, Mr. Edwards, but she cautioned me not to tell the others. They wouldn’t be interested anyway, she said.”

It’s a happy day when you’re elected cheerleader and when as you scribble happily, “We’re putting on my play, ‘The Princess Couldn’t Cry.’ Oh boy, Oh boy.

During your senior year, Terry Moore, you get a column in the school paper, The Explosion, and it’s typical of your all-out approach—whatever the problem—that you use the column to crusade for less sloppy male attire. You turn it into a boy’s fashion column, using the football stars for models, and you designate one day a week to be observed officially as “Slacks Day” at Glendale High. The boys begin dressing better, but the girls misjudge your motives. They suspect aloud that you’re using an unfair advantage to become better acquainted with the school athletes. Your journalism teacher, Mrs. Eva Litchfield, has a few why’s for this.

“Helen always put her whole heart into whatever she did, Mr. Edwards. She was doing a lot of fashion modeling then and she was trying to give the other students the benefit of her own experience. The boys had been living in blue jeans and I must say their dress improved. But that year Helen was on 21 Magazine and, well, some of the students never quite accepted her one hundred per cent. But then you pay for what Helen has. Talent always pays a price. Genius in whatever form a to climb the hard way. And talent like Helen’s, which showed itself even in youth, always pays a price.”

That price for you, Terry Moore, in the years to come will seem high.

January, 1947. You graduate midterm from Glendale High School with mixed emotions. Now you can really work full time in your world of make-believe. You can become the actress you’ve hoped to be. But you’re leaving half of your life behind. This girl now named Jan Ford—what will her future be?

It’s September, 1947, and you sign with Columbia Studios for the lead in “The Return of October,” a part you’ve won over many more famous actresses who tested for it.

You take the name of the girl in the film, Terry, and the last half of your mother’s name, Bickmore. And now you’re stardom-bound. It’s evident to James Gleason, who portrays your beloved Uncle Willie in the picture and who is supposedly reincarnated in the form of a race horse. We have it right from the “horse’s mouth, too.

“Yes, sir, Ralph. With Terry’s talent I had no doubt about her future. She showed great promise then, not only as an actress but as a person. That ermine bathing-suit thing. All that uproar was a typhoon in a thimble if you ask me.”

On January 1, 1951, you have your first date with football star, Glenn Davis. And your whirlwind romance catches the eye of cinema cupids everywhere. When he goes to Hawaii with a ball team, you and your mother go along and vacation there. Amid the romantic lush island atmosphere, with musicians playing Hawaiian love songs to you, he proposes. He’s the famous All American football hero, the story-book prince on a white horse and you agree to marry him.

February 8—five weeks after that first date—you’re married in Glendale in the room adjoining the Mormon Church Chapel where you’ve worshipped for so many years. You honeymoon in romantic Acapulco, and on February 24, 1951, leaving half your life behind you, you go to Lubbock, Texas, where your husband is employed by an oil company. You have a small apartment right next door to the local movie theatre.

Try as you will, Terry Moore, you cannot fit into this new life. You feel a stranger in this new far-flung land. You don’t understand the world of oil. Nor do they understand that which has been your world since you were eleven years old. There are personal problems between two who married on such short acquaintance that no story-book wedding and no strains of “Sweet Leilani” could ever solve.

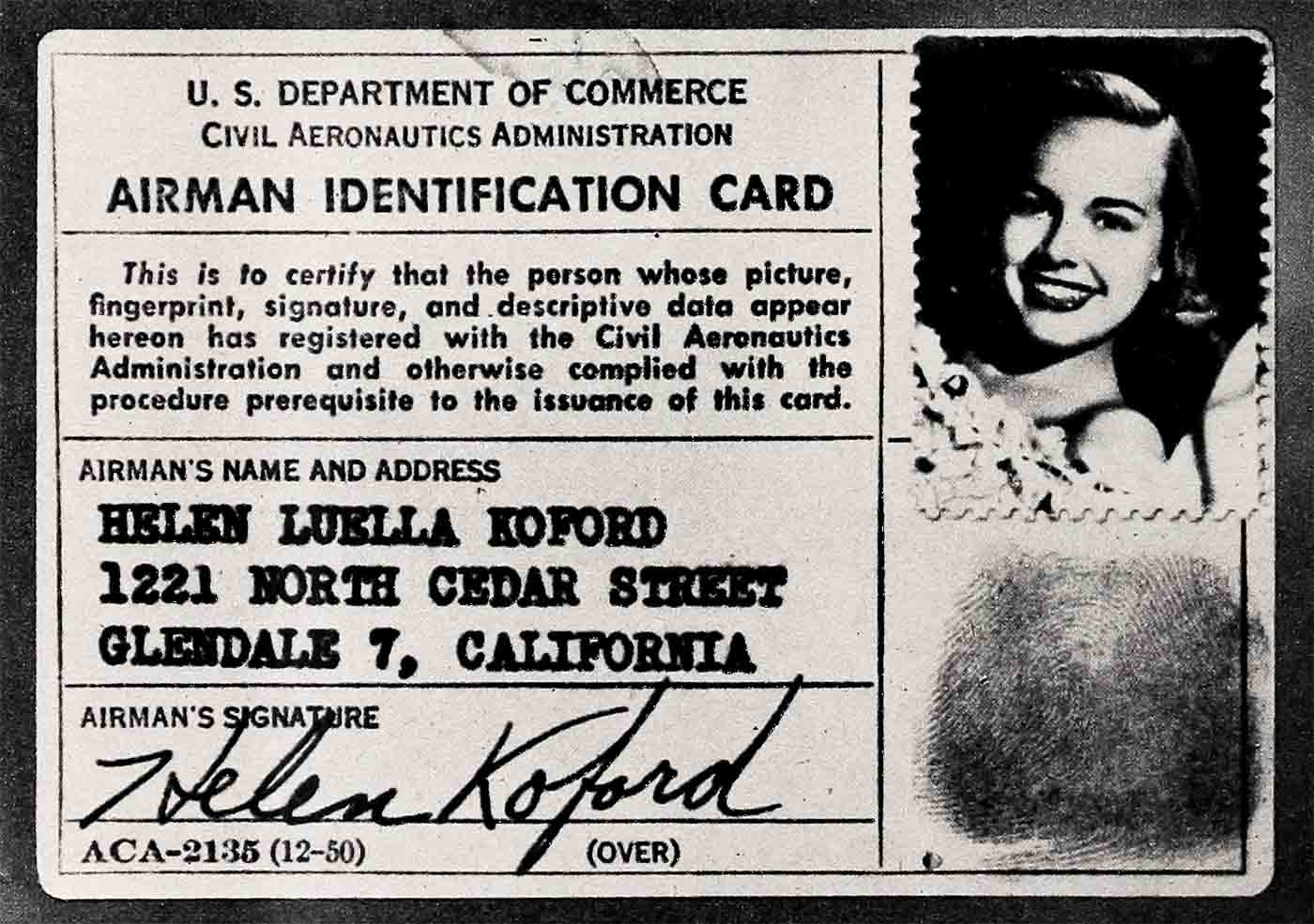

August 18, 195l—you announce your separation and you plunge with feverish energy back to work in your familiar world.

December, 1951—you get your CAA Pilot’s license to pilot a single-engined aircraft. Some call it a publicity stunt. Some others still today—Pilot No. 1226668—doubt whether you can really fly. They should have been out at Clover Field that afternoon when your mother and your flying instructor, Ray Pignet of the 20th-Century Flying Service and a former test pilot, sweated out your second solo while scanning the sky for the speck that means you. Ray Pignet tells about it now.

“She’d been instructed to land in Oxnard, California, and there was no indication on our weather maps of trouble there. But when Terry got to Oxnard, she found she was caught in a rough north-and-south crosswind. If she’d landed, she could have cracked up easily. Tell some students to land in Oxnard and, come what may, they’ll land there. But not Terry. She went on to Santa Barbara and landed there instead.

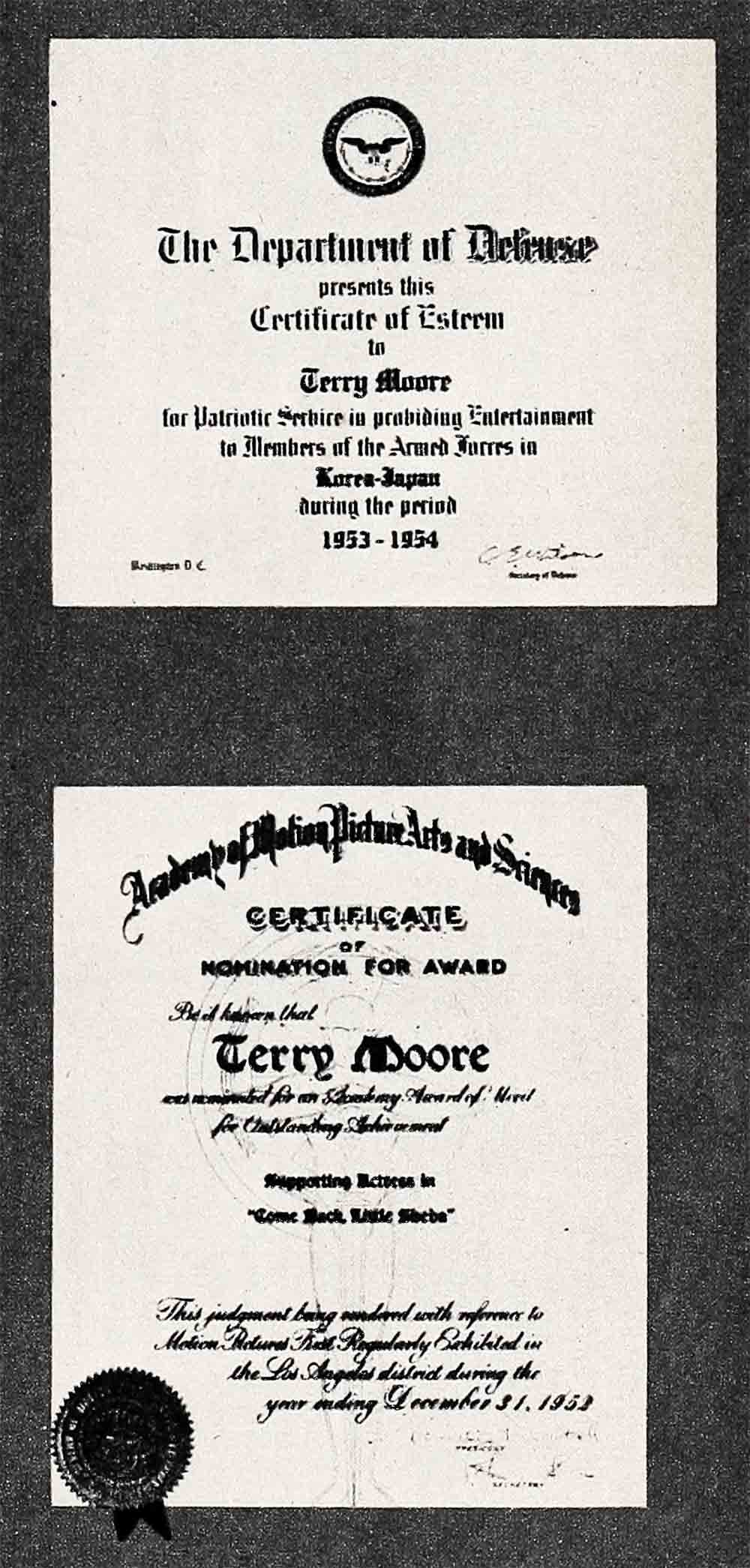

It’s another year now, Terry Moore, and you test with twenty-one others for the sexy college girl in “Come Back Little Sheba,” although it’s far from the sweet young things you’ve been playing. Director Daniel Mann is sold and he gives you the part.

February 17, 1953—You’re making personal appearances in San Francisco when you get the happy word that for your fine performance in “Come Back Little Sheba” you’ve been nominated for Hollywood’s highest honors, the Academy Award. This is more than even you had hoped for from your world of make-believe. This seems almost too good to be true. But for you, Terry Moore, even this is a divided victory. Triumph for Terry the actress, and tears for Terry the girl. You’re so good in the part you convince many you really are that girl and they identify you with the little sexy siren from now on.

September, 1952—Ace director Elia Kazan gives you the romantic young lead in “Man on a Tightrope.” On January 2, 1953, the fairy tale finally comes true. You sign a long-term contract at 20th Century-Fox, where a little girl in pinafore and pigtails ventured in the magic world of make-believe thirteen years ago. You’re given star billing in “Beneath the 12-Mile Reef” with Robert Wagner and then you co-star with Tyrone Power in “King of the Kyber Rifles,” directed by Henry King, who directed that first scene cut out of “Maryland” in that long-ago first assignment.

Your name is news now, Terry Moore, big news, and rumor. Sometimes mistaken rumor that hits to the heart of Helen Luella Koford, not so long ago of Glendale High. The little girl who suffered when she was called “Skinny” is avenged. She’s the queen of cheesecake now, and her legs are among the most photographed in the land, but again hers is a divided triumph. You’re a top target today and on Christmas—even in Korea—your whole world crashes around you and the Little Princess has feet of clay.

“You pay for what Helen has,” your teacher said. Talent pays a price and for eal the price seems finally almost too high.

Christmas Eve, 1953, on a cot in a hut in Korea, you’re sobbing your heart out. The setting is far removed, but for you it’s the same old story.

You’re heartbroken that you can be so misjudged. Again every stab hits an old and familiar wound. You’re a big girl now. Today there’s no diary to talk to, but the hurt is still the same. You wonder where you have failed. And why. You’ve worked toward today’s stardom for fourteen long years. And you’ve gotten there without ever stepping on anybody else.

You’ve also gotten jobs, many jobs, for others who will never know they’re indebted to you. And for a few like Darryl Hickman who discover it, but not from you. “I found out a year and a half ago when I got a call out of the blue from director Elia Kazan,” he says. “I’d never met him and you can imagine my surprise when he told me many of the nice things Terry had said about me. When I make ‘East of Eden,’ there’s a part in it for you’ Kazan said. One other day I got another call from him. Back in Hollywood again to cast the picture, he’d called Terry and again she’d put in a plug for me. How many people will go out of their way these days to do this? How many people ever have? About Terry I could tell you so much, Ralph. This is only one of many things.”

So many things, Darryl Hickman, and so many voices, Terry, from your past and present who want to speak for you.

Two years ago a beautiful talented girl with everything to live for, Yvonne Lohn, with whom you worked as a child in pictures, was stricken with polio. Today she is completely paralyzed. Her mother, Mrs. Winifred Lohn, can tell how much you mean to her. “No, I can’t tell you how much, Mr. Edwards. How can you measure the will to live? Or faith in God? That’s what Terry means to my Yvonne. On Saturday nights when a pretty star like Terry should be out dancing she takes Yvonne to a drive-in and to the show. She always sees there’s a friend along, a husky athlete, big enough to carry my daughter’s wheel chair in and out. On Sunday mornings she takes her to church. After church she invites people over to her home to meet Yvonne. It’s hard for a girl not to ask herself why this should happen to her. It’s hard for her to want to live. But Terry’s determined. How can a mother measure what Terry means to my daughter?”

Yes, you’re pinned up in the hearts of many people whom the public will never know. By many deeds no one can measure. And on April, 1954, Terry Moore, you are honored by a vast gathering of veterans of the Air Force. By fighter pilots and bombers who’ve fought our skies free wherever war clouds gather. You sit beside General Kenney. You hear yourself introduced as the “Army’s own Terry Moore, the girl who’s done so much to further the aims to which we are pledged.”

There’s a plaque for you, too. A pair of bronze boots. Your boots from the Korean tour. The Princess can’t cry but you do. For these are no silver slippers. These are real and they fit.

This is your life, Terry Moore, and your destiny. Talent pays a price for what you have. You pay. What you give to others someday will light the way to your own deserved happiness.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954

No Comments